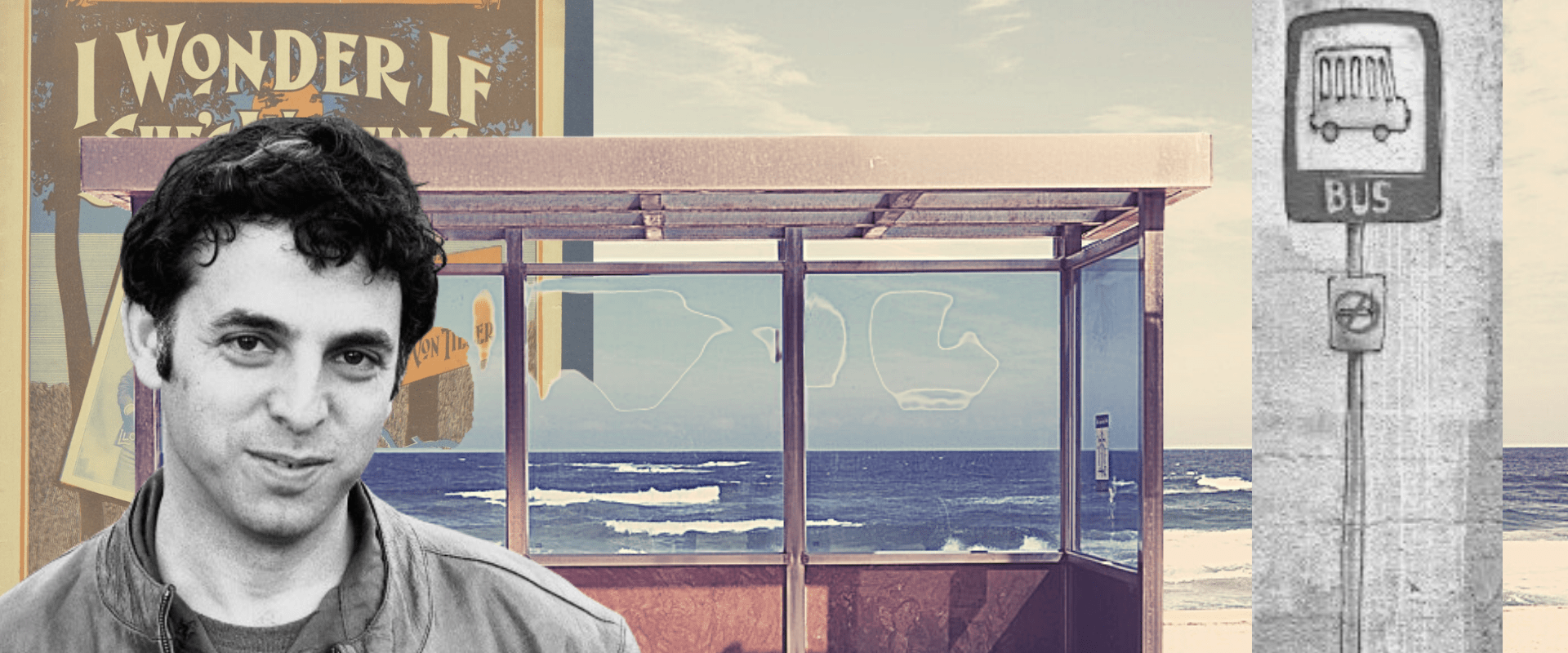

Only in one of Etgar Keret’s marvelously imaginative short stories can a bus driver with a social-minded ideology, an assistant cook with a sleeping disorder and blissful Happiness all converge.

Etgar reads a story which is as heartfelt as it is hilarious. This piece originally aired back in 2016, as part of one of our most popular episodes, Stop That Bus!

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Now, when we first began our show, one of the most exciting things was getting to work with Etgar, whose wonderful stories we had all grown up reading, and even studying. I recently asked him what it’s like to be canonized. To have every Israeli high schooler study, and be tested on, his creations.

Etgar Keret: Yeah, well, the truth is that once I tried to help a high school kid with some homework he had about me, and he got a very low mark after writing what I told him to write, so I stopped doing that.

Mishy Harman: It’s like Janet Jackson, she went to a Janet Jackson lookalike competition and came in third place.

Etgar Keret: [Laughs]. At least she was one of the top three. But I think that this idea that, you know, that people should take tests about my stories, there is something about it that is a little bit, kind of, fills me with anxiety. You don’t want any piece of art to be compulsory. And it’s for me, it’s strange that, you know, the ways that the literature is being taught as… like the same ways that you teach math when for me kind of teaching literature is a little bit like teaching… I don’t know, getting a massage or hanging around in your backyard. It’s kind of something that it’s for me, it’s kind of more fun and some kind of an emotional activity, you know, than profession or the topics that you learn in school.

Mishy Harman (narration): So if you ever wanted to practice your ability to get a massage or hang around your backyard, this is your chance. Here’s Etgar Keret’s short story The Bus Driver Who Wanted To Be God, read by Etgar himself.

Etgar Keret (narration): This is a story about a bus driver who would never open the door of the bus for people who were late. Not for anyone: Not for repressed high school kids who’d run alongside the bus and stare at it longingly. Certainly not for high-strung people in windbreakers who’d bang on the door as if they were actually on time and it was the driver who was out of line. And not even for little old ladies with brown paper bags full of groceries who struggled to flag him down with trembling hands.

And it wasn’t because he was mean that he didn’t open the door, because this driver didn’t have a mean bone in his body; it was a matter of ideology.

The driver’s ideology said that if the delay that was caused by opening the door for someone who came late was just under thirty seconds, and if not opening the door meant that this person would wind up losing fifteen minutes of his life, it would still be more fair to society, because the thirty seconds would be lost by every single passenger on the bus. And if there were, say, sixty people on the bus who hadn’t done anything wrong, and had all arrived at the bus stop on time, then together they’d be losing half-an-hour, which is twice fifteen minutes.

This was the only reason why he’d never open the door. He knew that the passengers hadn’t the slightest idea what his reason was, and that the people running after the bus and signaling him to stop had no idea either. He also knew that most of them thought he was just an SOB, and that personally it would have been much, much easier for him to let them on and receive their smiles and thanks. Except that when it came to choosing between smiles and thanks on the one hand, and the good of society on the other, this driver knew what it had to be.

The person who should have suffered the most from the driver’s ideology was named Eddie, but unlike the other people in this story, he wouldn’t even try to run for the bus, (that’s how lazy and wasted he was). Now, Eddie was an assistant cook at a restaurant called “The Steakaway,” which was the best pun that the stupid owner of the place could come up with. The food there was nothing to write home about, but Eddie himself was a really nice guy — so nice that sometimes, when something he made didn’t come out well, he’d serve it to the table himself and apologize.

It was during one of these apologies that he met Happiness, or at least a shot at happiness, in the form of a girl who was so sweet that she tried to finish the entire portion of roast beef that he brought her, just so he wouldn’t feel bad. And this girl didn’t want to tell him her name or give him her phone number, but she was sweet enough to agree to meet him the very next day at five at a spot they decided on together — at the Dolphinarium in Tel Aviv, to be exact.

Now, Eddie had this condition. It had already caused him to miss out on all sorts of things in life. It wasn’t one of those conditions where your adenoids get all swollen or anything like that, but still, it had already caused him a lot of damage. This sickness always made him oversleep by ten minutes, and no alarm clock did any good. That was why he was invariably late for work at “The Steakaway” — that, and our bus driver, the one who always chose the good of society over positive reinforcements on the individual level.

Except that this time, since happiness was at stake, Eddie decided to beat the condition. And instead of taking an afternoon nap, he stayed awake and watched television. Just to be on the safe side, he even lined up not one, but three alarm clocks, and ordered a wake-up call to boot.

But this sickness was incurable, and Eddie fell asleep like a baby, watching the Kiddie Channel. He woke up in a sweat to the screeching of a trillion million alarm clocks – ten minutes too late – rushed out of the house without stopping to change, and ran toward the bus stop. He barely remembered how to run anymore, and his feet fumbled a bit every time they left the sidewalk. The last time he had run was before he discovered that he could cut gym class, which was about in sixth grade, except that unlike in those gym classes, this time he ran like crazy, because now he had something to lose, and all the pains in his chest and his Lucky-Strike-wheezing were not going to get in the way of his pursuit of happiness.

Nothing was going to get in his way. Except our bus driver, who had just closed the door, and was beginning to pull away.

The driver saw Eddie in the rear-view mirror, but as we’ve already explained, he had an ideology that, more than anything, relied on a love of justice and on simple arithmetic. But Eddie didn’t care about the driver’s arithmetic. For the first time in his life, he really wanted to get somewhere on time. And that’s why he went right on chasing the bus, even though he didn’t have a chance.

Suddenly, Eddie’s luck turned, but only halfway: A hundred yards past the bus stop there was a traffic light. And, just a second before the bus reached it, the traffic light turned red. Eddie managed to catch up with the bus and to drag himself all the way to the driver’s door. He didn’t even bang on the glass, he was so weak. He just looked at the driver with moist eyes, and fell to his knees, panting and wheezing.

And this reminded the driver of something — something from his past, from a time even before he wanted to become a bus driver, when he still wanted to become God. It was kind of a sad memory because the driver didn’t become God in the end, but it was a happy one too, because he became a bus driver, which was his second choice.

And suddenly the driver remembered how he’d once promised himself that if he became God in the end, he’d be merciful and kind, and would listen to all his creatures. So when he saw Eddie from way up in his driver’s seat, kneeling on the asphalt, he simply couldn’t go through with it. And in spite of all his ideology and his simple arithmetic, he opened the door, and Eddie got on, and didn’t even say thank you, he was so out of breath.

The best thing would be to stop listening here, because even though Eddie did get to the Dolphinarium on time, Happiness wasn’t there. Because Happiness already had a boyfriend. It’s just that she was so sweet that she couldn’t bring herself to tell Eddie, so she preferred to stand him up.

Eddie waited for her on the bench where they’d agreed to meet for almost two hours. While he sat there he kept thinking all sorts of depressing thoughts about life, and while he was at it he watched the sunset, which was a pretty good one, and thought about how charley-horsed he was going to be later on.

On his way back, when he was really desperate to get home, he saw his bus in the distance, pulling in at the bus stop and letting off passengers. He knew that even if he’d had the strength to run, he’d never catch up with it.

So he just kept on walking slowly, feeling about a million tired muscles with every step.

When he finally reached the bus stop, he saw that the bus was still there, waiting for him. And even though the passengers were shouting and grumbling to get a move on, the driver waited for Eddie, and didn’t touch the accelerator till Eddie was seated.

And when they started moving, he looked in the rear-view mirror and gave Eddie a sad wink, which somehow made the whole thing almost bearable.

In April 2020, during the early weeks of the pandemic, we hosted Etgar for a Facebook Live event. We invite each and every one of you to join our members-only Facebook Community. You’ll immediately become part of a vibrant group of Israel Story fans, and will also be able to watch – or rewatch – the entire conversation with Etgar. But for those who prefer to listen, we bring you a much shorter, and edited, version of that chat.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Back in the early weeks of the pandemic, in what now seems like a lifetime ago, we ran a series of live update interviews with some of the most memorable people who’ve appeared on the show over the years. Needless to say, Etgar – who by now has become a dear friend – was one of our first guests.

Mishy Harman: So Etgar, I guess my first question is that we’re in a time of isolation, obviously. What kind of advice can you give us about how to be isolated and how to connect with yourself in isolation?

Etgar Keret: Well, I must say that, you know, for me, it’s kind of a default. With the coronavirus, I feel that more and more people are taking to my lifestyle, you know? It’s not as if I had to do that many adjustment because I usually, if I’m not traveling, I stay indoors. I take walks twice a day and speak most of the time to my son or to my wife. And the core things kind of stayed the same. But I want to say that there is something about writing in general that I find that writing is a great way to deal with loneliness or with solitude. Because when you write stories, you kind of invent yourself a world and you invent relationships and conflicts and tensions. So you kind of like, you know, this kind of sentence “get a life?” So you maybe you don’t get a life, but you make a life, you know? So you’ll have a life. You kind of… you’re self-sufficient. But creating these stories really, really a way to feel that you belong to something bigger than yourself. So for me, I feel like in the past few weeks I’ve written a lot because I… I needed to connect, and that was the only way to do it.

Mishy Harman: So if you could choose one thing that you hope that we learn from this pandemic and emerge from it, in what way would the world be different?

Etgar Keret: For me, the most obvious thing to learn about it is some kind of lesson in solidarity. I think that basically the narrative was everybody needs to take care of himself. But here we are in a situation where you have to take care of your health so I will live, you know? And this idea of kind of realizing that, you know, that we’re all connected. So there is this thing about this kind of outside threat that maybe it should show us more what all have in common as human beings.

Mishy Harman: Etgar, you often talk about the influence of authors like Kafka and Bashevis Singer on you. But can you tell us a little bit about the influence of the greatest storytellers – people who told you stories and impacted you in terms of… of being a storyteller?

Etgar Keret: Yeah, well, I think I think there was something in my family that storytelling was very, very important. My parents being kind of self-educated children of Holocaust – in my mother’s case, an orphan from both a mother and a father – this idea of kind of making sense out of the world was essential. And I think that the only way that they thought of doing it is by structuring it as a story. So the world could be a scary story in which we should be afraid or a funny story or an uplifting story. But it was this idea that there were building some kind of a narrative about life through, through the choices they took. My father, there was something about the way that he would tell things that, you know, is it even he if he would tell a story about a period in which he lived in a whorehouse, you know? Or some kind of interaction that he had with the Italian mafia to buy weapons for the Irgun in which he served. There was something about stories that whatever kind of happened, whatever people would do, even if it would be very, very extreme, he would have some kind of understanding for it, you know? It’s like he would kind of feel where it was coming from and, even if he would not agree with it, he would accept it.

Mishy Harman: And Etgar, one of the things that I most admire about you and that I have learned from you is your sense of curiosity around the world. So the most mundane experience of going to the corner shop to buy some milk becomes an adventure in your mind, and you notice all kinds of unusual things and… How do you manage to maintain that and not sort of become accustomed to the world or cynical to its ways?

Etgar Keret: Well, the truth is, that you know, I think that maybe you need to be dumb enough because I feel that the world kind of keeps surprising me. I see things that I don’t expect and this kind of unpredictability of it is something that always excites me, you know? I am the kind of guy when I see movies, many times I can tell you after like ten minutes what’s going to happen and who’s going to die and who’s the murderer. I’m very good at that when it… when it comes to stories. But when it comes to life, you really see that there is something so beautifully scripted, you know? That so many times I don’t see where we going, where we are heading. And some of those changes, you know, sometimes they can be so uplifting emotionally. I’m excited because it’s exciting.

Mishy Harman: Etgar, thank you so, so much for your time and for all of your thoughts.

Etgar Keret: Thank you, toda, bye bye.

Mishy Harman: Bye.

The Facebook Live event was produced by Marie Röder and Yoshi Fields, with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Alicia Vergara created the artwork for the episode. Thanks to Julie Subrin and Or Matias. The end song, Atid Matok (‘Sweet Future’), is by Mashina.