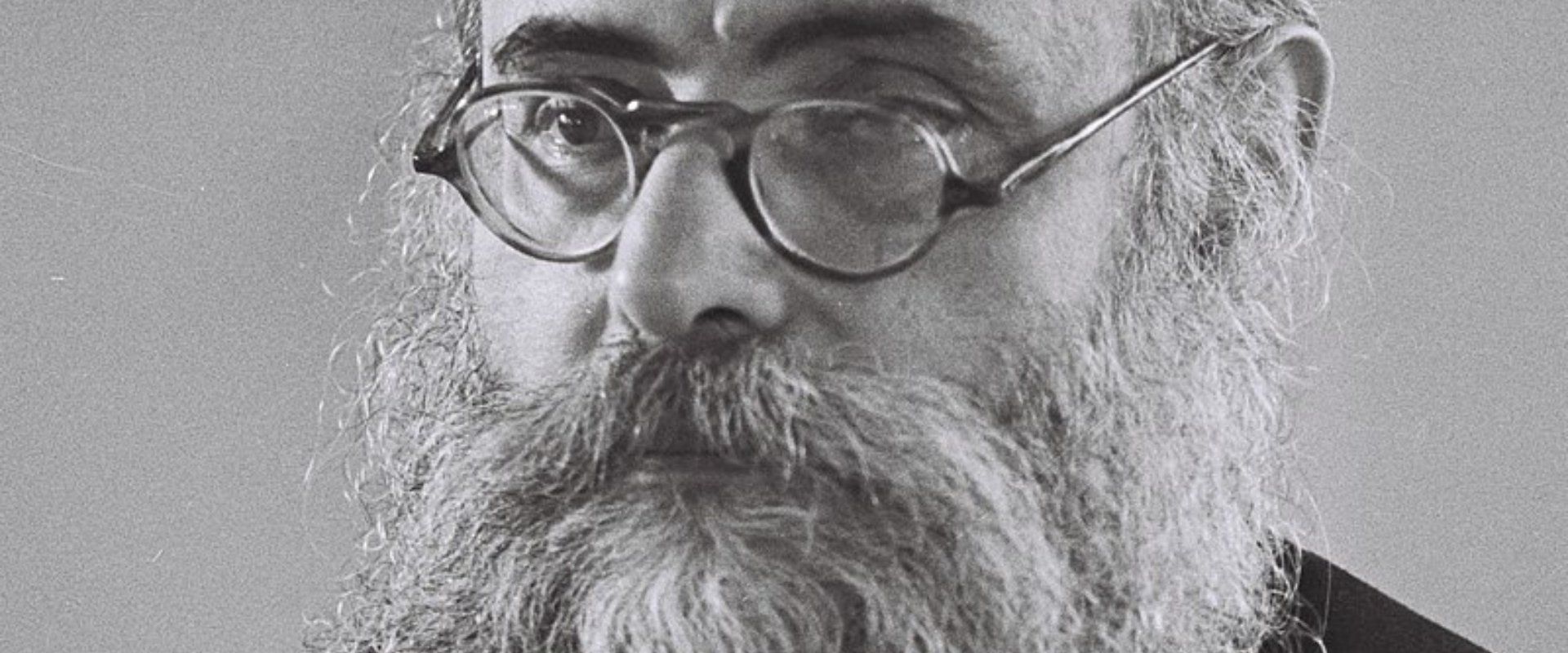

Rabbi Yitzhak Meir Levin was – in every way possible – Hasidic royalty. He was born in 1893 in the Polish town of Góra Kalwaria, or – as it’s known in Yiddish – Ger. And was not only the grandson of the third Gurreh Rebbe, the Sfas Emes, but also married to the daughter of the fourth Gurreh Rebbe, the Imrei Emes.

In 1930, at the age of 37, Rabbi Levin was appointed the head of the Polish branch of Agudas Yisroel, a Haredi political movement that – in pre-war Europe – had an estimated one million followers.

In the Spring of 1940, the top rabbis of the Gurreh hasidic court – who were wanted by the Gestapo – all went into hiding in Warsaw. An emergency message was soon conveyed to their followers in the United States, and thus began a chain reaction that resulted in a handful of visas being smuggled into occupied Poland. These were, naturally, given to the leadership – including Levin – who reluctantly left behind children, grandchildren and hundreds of thousands of followers, most of whom would ultimately be murdered by the Nazis.

Levin arrived in Mandatory Palestine in May 1940. Once here, he was a member of the Jewish Agency’s Rescue Committee for European Jewry, where he repeatedly clashed with secular Zionist leaders, who often found themselves in an impossible situation: While millions of Jews – including their own family members – were being slaughtered in Europe, they were busy trying to build a new society in the Land of Israel. With extremely limited resources at hand, how do you decide what should take precedence?

Levin’s greatest nemesis was fellow future signatory of the Declaration of Independence and Israel’s first Interior Minister, Yitzhak Grünbaum, who went on record saying that not a single cent of the JNF’s funds ought to be spent on rescuing Europe’s Jews.

During those first years in the Land of Israel, Levin was forced to plot a path through the thickets of Jewish and Zionist politics. Should the Agudah party support the establishment of a State, or else adopt an anti – or at least a non– Zionist stance? His answer to this question would have lasting repercussions that continue to reverberate within Israeli society to this very day.

As part of the dilemma, he and other Haredi leaders negotiated matters of religion and state, including – and perhaps most famously – the exemption from military service for 400 yeshivah students, shetoratam umanutam, or whose “studying is their trade.” This compromise eventually ballooned into a widespread and controversial phenomenon with extensive social, political and economic ramifications.

In June 1947 Levin was among those who managed to secure what has come to be known as the “Status Quo” Letter. In that now-famous document, Ben-Gurion promised – among other things – that Shabbat will be the official day of rest in the state-to-be, that kitchens in public institutions will be kosher, and that matters of marriage and divorce will adhere to the dictates of Orthodox Judaism.

With these assurances in hand, Levin agreed to sign the Declaration, despite his many misgivings about its secular nature. Inking his name was, perhaps, made slightly easier by the fact that he didn’t actually attend the Declaration ceremony itself. On May 14, 1948, as the members of Moetzet HaAm congregated in Tel Aviv, he was out fundraising for Agudas Yisroel in far-away New York City, and added his signature to the scroll later on.

After the establishment of the State, Levin served as Israel’s first Minister of Welfare. Four years later, he quit his cabinet post in protest over the notion of women serving in the IDF.

He died in Jerusalem in 1971, at the age of 78, and was buried on the Mount of Olives.

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: there were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

Today we’ll meet Yitzhak Meir Levin, and his great-grandson, Hanoch Zvi Rubinstein. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Act TranscriptHanoch Zvi Rubinestein: [Chanting of Hassidic song]. I’ve seen a letter he wrote to his family, in which he’s describing getting close to Jerusalem. It was all very difficult, the roads were windy, hard to navigate. But he writes to them, “I can’t even begin to describe my excitement. I am now about to enter Jerusalem. The holy city of Jerusalem. The place we’ve all dreamt about, and longed for, and spoken about in our prayers, for two thousand years. Two thousand years! And here I am, here. What a privilege. I myself am here.” It was an extraordinary excitement. [Chanting of Hassidic song].

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Rabbi Hanoch Zvi Rubinstein, one of roughly fifty great-grandchildren of Rabbi Yitzhak Meir “Itche Meiyer” Levin, the foremost Haredi rabbi to have signed the Declaration of Independence.

[Signed, Sealed, Delivered? introduction]

Today we’ll meet Yitzhak Meir Levin, and his great-grandson, Rabbi Hanoch Zvi Rubinstein. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series. Here’s our senior producer, Yochai Maital, with Hanoch Zvi Rubinstein, Yitzhak Meir Levin’s great-grandson.

Yochai Maital (narration): Rabbi Yitzhak Meir Levin was – in every way possible – Hasidic royalty. He was born in 1893 in the Polish town of Góra Kalwaria, or – as it’s known in Yiddish – Ger. And not only was he the grandson of the third Gurreh Rebbe, the Sfas Emes, but he was also married to the daughter of the fourth Gurreh Rebbe, the Imrei Emes.

In 1930, at the age of 37, Rabbi Levin was appointed the head of the Polish branch of Agudas Yisroel, a Haredi political movement that – in pre-war Europe – had an estimated one million followers.

Three years later, in November 1933, Levin was arrested. Reporting on this, quote, “sensational” news, the Doar Hayom daily revealed that the Polish police had found a baggy of possibly “intoxicating substances” in Levin’s home. In fact, as it later turned out, it was a bag filled with soil taken from the grounds of Rachel’s Tomb.

In the Spring of 1940, the top rabbis of the Gurreh hasidic court – who were wanted by the Gestapo – all went into hiding in Warsaw. An emergency message was soon conveyed to their followers in the United States, and thus began a chain reaction that resulted in a handful of visas being smuggled into occupied Poland. These were, naturally, given to the leadership – including Levin – who reluctantly left behind children, grandchildren and hundreds of thousands of followers, most of whom would ultimately be murdered by the Nazis.

Levin arrived in Mandatory Palestine in May 1940. Once here, he founded and ran the Jewish Agency’s Rescue Committee for European Jewry. In that role he repeatedly clashed with secular Zionist leaders, who often found themselves in an impossible situation: While millions of Jews – including their own family members – were being slaughtered in Europe, they were busy trying to build a new society in the Land of Israel. With extremely limited resources at hand, how do you decide what should take precedence?

Levin’s greatest nemesis was fellow future signatory of the Declaration of Independence and Israel’s first Interior Minister, Yitzhak Grünbaum, who went on record saying that not a single cent of the JNF’s funds ought to be spent on rescuing Europe’s Jews.

During those first years in the Land of Israel, Levin was forced to plot a path through the thickets of Jewish and Zionist politics. Should the Agudah party support the establishment of a State, or else adopt an anti – or at least a non- Zionist stance? His answer to this question would have lasting repercussions that continue to reverberate within Israeli society to this very day.

As part of the dilemma, he and other Haredi leaders negotiated matters of religion and state, including – and perhaps most famously – the exemption from military service for 400 yeshivah students, shetoratam umanutam, or whose “studying is” – as the phrase goes – “their trade.” This compromise eventually ballooned into a widespread and controversial phenomenon with extensive social, political and economic ramifications.

In June 1947 Levin was among those who managed to secure what has come to be known as the “Status Quo” Letter. In that now-famous document, Ben-Gurion promised that Shabbat will be the official day of rest in the state-to-be, that kitchens in public institutions will be kosher, and that matters of marriage and divorce will adhere to the dictates of Orthodox Judaism.

With these assurances in hand, Levin agreed to join Moetzet HaAm and sign the Declaration, despite his many misgivings about its secular nature. Inking his name was, perhaps, made slightly easier by the fact that he didn’t actually attend the Declaration ceremony itself. On May 14, 1948, he was out fundraising for Agudas Yisroel in far-away New York City, and he only added his signature to the scroll later on.

After the establishment of the State, Levin served as Israel’s first Minister of Welfare. Four years later, he quit his cabinet post in protest over the notion of women serving in the IDF. In 1969, he also objected to the election of Golda Meir as Prime Minister arguing that a female head of state would harm Israeli deterrence.

He died in Jerusalem in 1971, at the age of 78, and was buried on the Mount of Olives.

Here he is, in a 1961 recording, discussing his concerns regarding modern-day Israel.

Yitzchak Meir Levin: Whatever we’re able to accomplish in the State, everything we build, every stone, every blade of grass, will gladden the heart of every Jew. But over the course of the last two thousand years we’ve forgotten our essence. That’s what’s missing, in my opinion. When I was in the government, I told my colleagues – on at least four different occasions – that we need to sit down and educate ourselves about what it is to be Israel. About the meaning of being Israel. What is the content, and what is the essence of Israel? I said this as soon as I entered the government. And now, after thirteen years of statehood, we need, even more so, to remind ourselves what our vision is, and what our mission should be. I have not a shadow of a doubt that the only answer – and we truly have no other path – is to return to the bedrock of our existence.

Hanoch Zvi Rubinestein: My name is Hanoch Zvi Rubinstein, and I’m the great-grandson of Rabbi Yitzhak Meir Levin, may the memory of the tzaddik be a blessing. Rabbi Yitzhak Meir HaCohen Levin was born in Taf Resh Nun Dalet, or 1893. When he was 13, he was engaged to his cousin, his uncle’s daughter. That uncle, the Gurre Rebbe, was known as the ‘Elder Admor M’Gur,’ and was the leader of the Gur Hasidim for over forty years. So my great-grandfather essentially grew up in the Rebbe’s court, in his shadow, up until World War One. That’s when he moved to Warsaw and himself became the leader of Haredi Jewry in Poland. In Taf-Shin, or 1940, my great-grandfather was living in Warsaw and was asked to serve on the Judenrat, together with Adam Czerniaków. See, the two of them were Jewish leaders of very different kinds and represented very different Jewish communities – my great-grandfather was haredi and Czerniaków was a secular engineer and politician. So the Nazis chose the two of them to lead their so-called ‘Jewish Council.’ But my great-grandfather immediately understood what that meant, and tried to get out of it. He participated in the first meeting of the Judenrat and said that he couldn’t possibly work for the Nazis, even if – as the Nazis kept on saying – their intentions were good. He thought it was simply out of the question for him to collaborate with them. So he went into hiding. And he told Czerniaków, he said, “look, I know you. You’re an honest and decent man. You won’t be able to go ahead with it. You won’t be able to send fellow Jews to their death.” And what can I say? That prophecy fulfilled itself. Two years later, in 1942, when the deportations from the Warsaw Ghetto began, Czerniaków just couldn’t follow the Nazis’ orders anymore and, well, took his own life. But by the time Czerniaków committed suicide in Warsaw, my great-grandfather, Rabbi Levin, was already long gone and far away. See, back in 1940 he went underground. The Nazis were searching for him everywhere, and then – at the end of that first terrible winter of 1940 – he managed, together with his father-in-law, the Gurre Rebbe, to escape. They got immigration certificates, fled via Italy, and made aliyah to the Land of Israel during Passover of 1940. When he arrived in the Land of Israel, he had to start from scratch. All his followers – nearly a million Jews who shared his lifestyle and his aspirations – they all remained in Europe, and he was here. Alone. A shepherd without a flock. And here he was thrown into a whole new reality, a whole new struggle. There were bitter disputes about a very simple question: What’s our ultimate goal – saving the Jews of Europe or building a Jewish state in the Land of Israel? And, as part of that, where do we direct our efforts, our funds? Yitzhak Gruenbaum – who was one of the heads of the Jewish Agency – argued, with great passion, that we were working for the future State of Israel, for Zionism. And Rabbi Yitzhak Meir Levin – my great-grandfather – said the exact opposite, that we ought to work for the sake of the people, for the sake of Jews, and that saving the lives of those who are being murdered at Auschwitz is more pressing, and more important – at least now – than investing in building the foundations of a state. He thought that should be the top priority. Despite all those deep arguments, he joined the leadership of the Yishuv and – as such – signed the Declaration. But to tell you that he did it wholeheartedly? Look, there were many things that he didn’t agree with. Take the first line of the Declaration, for example – “the Land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people,” OK? Now, we know – and he knew – that that just isn’t true. I mean it’s factually wrong. The Land of Israel was not the birthplace of the Jewish people. The Jewish people became a nation much much earlier, when we received the Torah at Mount Sinai. And it’s not that the statement in the Declaration was some sort of oversight or mistake or something. It was written intentionally. And by whom? By people who had turned their backs on religion and didn’t accept, or didn’t want to acknowledge, the fact that we became a nation, an Am, at Sinai. So instead they created a new origin myth, a Zionist one. And that’s how we ended up with a Declaration that claims that “the Land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people.” Things like that made many haredi people angry. And many of them turned their anger towards Rabbi Levin. They asked him how he could possibly sign a Declaration that includes such heresies and blasphemies. “You’re lending your name to something that completely negates what’s written in the Torah,” they said. But he didn’t see his signature as an affirmation of what was written in the Declaration. No. Instead, he signed on for a vision of the future, not a description of the past. But yes, yes, there was definitely an ongoing struggle, both within the community and within himself, as to what to do. Should he sign the Declaration or not? Should he join the government or not? Will it benefit the haredi population, the Jews, or will it be ruinous? There were many voices in this debate. Some, I would even say most, claimed that by supporting the creation of the State my great-grandfather was agreeing to a secular entity which stood in defiance of the Holy One Blessed Be He. But my great-grandfather and his party, Agudat Yisrael, said, “we didn’t establish this State. And if this State, to our great dismay, does all sorts of secular and blasphemous things that go against religion and against Judaism, that still doesn’t mean that we can just turn our backs on it and enter into our own cocoon or shelter. We need to be part of it – not because we share its vision, and not because we’re partners to its actions (even though in reality we are), but because following the hurban, following the Holocaust, we simply have to do whatever we can to salvage Judaism.” Once we have a State, he thought, the secular people will calm down, and realize that we aren’t the enemy. They’ll leave us alone and let us live our lives. So if that means that we have to sign a piece of paper here and there, or that we have to join the government, that’s OK. Because it serves the larger goal, which is to live proper Jewish lives. That was my great-grandfather’s way of thinking, and he acted accordingly. So he tacked on his signature. Immediately after the founding of the State, my great-grandfather was appointed to be the first Minister of Social Services. And I’ll tell you a story that will give you a sense of the kind of man he was. So the Minister of Social Services is in charge of the welfare system, and one day my great-grandfather was sitting in his office when a man showed up. And this man? He, well… was missing both his legs, may we never know such misfortune. Anyway, the guy came in, sort of hobbling on these wooden blocks, and asked to see the Minister. He wanted help getting into a certain institution for handicapped people. So my great-grandfather’s secretary came in and told him that there’s a man outside with no legs, sort of limping on the ground. And Rabbi Levin got up out of his chair, walked out to greet him, and sat down on the floor and spoke to him at eye level. That’s the sort of man he was. I myself grew up in Tel Aviv. And every morning, when I’d walk from our home to my talmud torah, to the Belz cheider, I had to pass through Sheinkin Street. And what can I tell you? The revolution – yes, the revolution – that’s taken place in Tel Aviv, even just from the time I was a little kid till today, is a source of great pain for me. When I was a kid we had secular neighbors and we all lived together, and respected each other. They knew, for instance, that we don’t turn on the lights in the building’s stairwell on Shabbat, so they’d wait until we passed before turning on the light. And it wasn’t a matter of religious coercion, or because we G-d forbid ever asked them for such a thing. It was just the way they behaved. A sign of respect. But today, the secular and the religious are growing farther and farther apart. What can I say? We, the Haredis, are sort of viewed in the same way that the settlers see the Arabs in the country. I mean, the message is, ‘OK, you’re here, you want to study, you’ve built this whole world of yeshivot, and that’s fine. But carry your share of the national burden!’ What people don’t understand is that we are carrying our share of the burden. We are pulling our weight. And it’s a very difficult load to bear, a very heavy load. It’s a burden that might not kill you, but it is a burden that’s very hard to live with. After all, we have a mission. You know, Yoseph Trumpeldor’s famous last words were “it’s good to die for our country.” We don’t agree with him. We don’t want anyone to die. We think that the Jew must live, not die, in sanctification of G-d’s name. But, and this is a big but, it’s harder to live in sanctification of G-d’s name than it is to die in sanctification of G-d’s name. And our yeshiva boys, who are all living in sanctification of G-d’s name, aren’t shown any appreciation. They get no respect for their sacrifice. And it is a real sacrifice. A thousand times a day they have to put aside their wishes, their desires, their material needs, all for what? For protecting our future by studying and preserving our tradition. So don’t tell me that these yeshiva boys aren’t carrying a load or aren’t pulling their weight. They absolutely are! Let me give you a recent example. A few weeks ago, Aharon Barak – the former President of the Supreme Court – gave an interview to a haredi newspaper. And at the end of the interview, which took place at his home, the two journalists asked him whether – as a Jew who grew up in the Kovno Ghetto – he’d like to put on tefillin. And Barak said he would. So they took out a pair of tefillin from their bag and wrapped it around his head and arm. There’s a video of the whole thing online. You can watch it if you want. Anyway, look, Justice Barak is definitely a talented man, someone who’s reached incredible heights and is important and respected by most people in this country, and by almost everyone in the world. And here he was, standing wrapped in tefillin reciting the Shema. Shema Yisrael HaShem Elokenu HaShem Ehad. Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is one. And then the two reporters asked him to continue. To recite the next verse “VeAhavta et HaShem Elokecha BeChol Levavcha U’Vechol Nafshecha U’Vechol Me’odecha…” “And thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thine heart, with all thy soul, with all thy might.” And what can I tell you? That’s a basic verse. A fundamental one. Even my three-year-old daughter knows it by heart. And to tell you the truth, the great Justice Barak didn’t really know it. And, well, that’s painful for me. On the other hand, he’s made other, even major, contributions. Contributions to the People of Israel. So can we say that just because Aharon Barak can’t recite basic prayers, he isn’t carrying his share of the load? Of course not. That’s ridiculous. Because sharing the national burden doesn’t mean that everyone has to do the same thing. Every person contributes where they can. Our goal isn’t to put haredis on the Supreme Court. Haredis should be part of, and lead, rabbinic courts. That of course. But justices on the Supreme Court? They shouldn’t be Haredi. I’m not looking for representation on secular courts, however important they might be. But I do hope that the justices on the secular courts will show understanding. Like take the issue of separation between the sexes in the public sphere for example. People here call it – even the courts call it – ‘religious coercion.’ But that’s not it at all. Calling it that shows a total lack of understanding of who and what we are. We have absolutely no desire to force our way of life on anyone. If someone doesn’t want to come to an event which is only for men, or an event that’s only for women, or an event in which there’s a separation between men and women, they don’t have to come. No one’s forcing them. But in the name of equality and all kinds of other lofty ideals, the secular courts don’t allow us to have segregated events in public spaces even for our own community. They say that would be imposing our religion on everyone. ‘Hadata’ they call it. That’s just so absurd that we don’t even have the strength, the wherewithal, to argue about it. It just shows a fundamental misunderstanding of our lives. So all I’m asking for are secular justices who will be understanding of our lifestyle. Who will get us. That’s all. To what extent do I believe that Israel has lived up to the ideals set forth in the Declaration of Independence? Well, look, the Declaration talks about Jewish immigration and the importance of Kibbutz Galoyot, ingathering the exiles. And in that sense it’s been an incredible success. Truly extraordinary. I mean, for that alone it was worth founding the State of Israel. Even today, Jews from anywhere in the world can come here. And just imagine how significant that was in the early days of the State, when Jews all over the place were dispersed and shattered and destitute, and suddenly they had a homeland that welcomed them in. You should know, by the way, how hard we fought, Agudat Yisrael too, for every single immigration certificate. So in that regard – in terms of Jewish immigration – we’ve totally fulfilled the promise made in the Declaration. But at the same time, instead of ingathering the exiles and then safeguarding them, or – in other words – preserving the variety of different Jewish traditions, the State took these immigrants and stripped them of their unique identities. They tried to make them into one kind of Jew. The kind of Jew that they saw fit. They took authentic and rich expressions of Judaism and tried to create a ‘New Jew.’ A new Jewish people. So that’s not the Kibbutz Galoyot we imagined. It’s a Jewish immigration that tries to remove the Jewish part. It also pains me to see that some people try to rebrand the Declaration as an anti-religious document. I mean, it isn’t a pro-religious document, and it isn’t an anti-religious document. You know, today everyone’s saying that the Declaration of Independence is the bedrock of our democracy. But the word ‘democracy’ doesn’t appear in the Declaration. It says, of course, that the State will be based on the idea of equality for all. That yes. But while the notion of Israel as a Jewish state is mentioned, the notion of Israel as a democratic state is not. And it’s hurtful that certain people take the Declaration and turn it into an indictment against the Haredi way of life. After all, our Declaration of Independence promised freedom of religion and freedom of conscience to everyone, to all people of all religions. But we still sort of feel as if we’re being “allowed” – almost as a favor – to live here and practice our religious lifestyle. There’s a sense that our religion, or at least our brand of religion, isn’t really tolerated. The truth is, we haven’t yet figured out how to live together, in the way that a single family, with different family members, lives together. I hope it will happen one day. Meanwhile, we maintain the hope that our Holy Messiah, mashiach tzidkenu, will come to this State and see all that we’ve prepared for him, and he will be very very moved.

Hanoch Zvi Rubinestein: In 1940, the Gurre Rebbe and my great-grandfather, Rabbi Levin, escaped Europe and arrived in the Land of Israel. And there’s a niggun, a song, from those days, that has since become a central part of our community, something we sing all the time. It goes like this. [Chanting of Hassidic song].

In 1961 Eliezer Whartman of the Israel State Archives conducted a series of interviews with 31 of the 37 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. For the full interview with Rabbi Yizhak Meir Levin, see here.

For a vivid account of the life and times of Rabbi Yizhak Meir Levin, see Yisrael Rubinstein’s biography, Meir LaDoros (Hebrew).

For a zoomed-out look at Levin’s life’s work, see this article from Makor Rishon (in Hebrew).

For an historical perspective on Levin’s decision not to serve as a member of the Judenrat, see this article, from the Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Center, on the history of the Warsaw Ghetto.

For the ‘Status Quo Model,’ as presented by Ben-Gurion to Levin and the Agudas Yisroel movement, see this article, by Supreme Court Justice, Daphne Barak-Erez, as well as this Kikar Ha’Shabbat article, in Hebrew, concerning the famous June 1947 letter itself.

For background on why the Agudas Yisroel Party opposed the appointment of Golda Meir as prime minister in 1969, see this article by the National Library staff.

For a video clip of Former Supreme Court President Aharon Barak putting on Tefillin, see here and here, and for Sephardic Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Yosef’s scathing critique of Barak’s unfamiliarity of the prayer, see here.

Lastly, here is Levin’s obituary in the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was edited by Adina Karpuj and mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubbers are Yoav Yefet and Jonathan Brenner.

The end song is Niggun Ger (arrangement – Eli Klein and Yitzy Berry), performed by Moshe Duvid Weissmandel accompanied by the Neshama Choir, conducted by Itzik Filmer.

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.