Tomorrow we’ll be celebrating the second Passover since the start of this war. People around the world will gather at Seder tables and talk about slavery and freedom, liberty and social justice. We’ll ask how this night is different from all other nights, and offer up some answers about bitter herbs and comfortable cushions. But the truth is that just like the previous 554 nights, there will be countless people – throughout the region – who won’t be reclined and sheltered, and countless Seder tables with empty seats and missing people. There will also be 59 hostages who are still being held in captivity in Gaza – people for whom the words of the Haggadah are, more than anything else, an accurate description of their daily lives. People who will say “this is the bread of affliction that our ancestors ate in the Land of Egypt” and know, in their growling stomachs, exactly what that means. People who will whisper, with the most deep-seated hope, “this year we are here, next year let us be in the Land of Israel. This year we are slaves, next year let us be free.”

And, at the same time, in homes scattered throughout the country and the world, there will also be thirty Israelis and five citizens of Thailand who did gain their freedom since the last Seder. People who – a year ago – were prisoners of the Hamas and other terrorist groups, and this year can, thankfully, celebrate the Seder at home with their families, or at least with what is left of their families.

Long before the war began, long before we could imagine what was just around the corner, we started working on a Passover episode that told the story of a small group of Israelis who – more than half a century ago – experienced their own exodus from Egypt, and their own journey from captivity to freedom. We sat on this piece for a long time, because – with all that has transpired since October 7th, it has accrued painful layers of meaning we could have never anticipated. And today, with both sadness and hope, we share it with you.

There and Back Again: A Tale of a Very Different Exodus from Egypt.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Hey, I’m Mishy Harman and this is Israel Story. Israel Story is brought to you by the Jerusalem Foundation and The Times of Israel.

Next week we’ll be celebrating the second Passover since the start of the war. People around the world will gather at Seder tables and talk about slavery and freedom, liberty and social justice. We’ll ask how this night, this Seder, is different from all other nights. We’ll offer up some answers about bitter herbs and comfortable cushions, but the truth is that once again, just like the previous 554 nights, there will be countless people, throughout the region, who aren’t reclined and sheltered, but are rather suffering and homeless and feeling pain. There will be countless Seder tables with empty seats and missing people.

I’m recording this in late March, and pray in every possible way that by the time it airs it will no longer be true, but at least as of today, there will also be Israeli hostages who are still held in captivity in Gaza. People for whom the words of the Haggadah are – more than anything else – an accurate description of their daily lives. People who will say “this is the bread of affliction that our ancestors ate in the Land of Egypt” and know, in their growling stomachs, exactly what that means. And people who will whisper, with the most deep-seated hope, “this year we are here, next year let us be in the Land of Israel. This year we are slaves, next year let us be free.”

And, at the same time, in homes scattered throughout the country and the world, there will also be thirty Israelis and five citizens of Thailand who did gain their freedom since the last Seder. People who – a year ago – were prisoners of the Hamas, and this year can, thankfully, celebrate the Seder at home with their families, or at least with what is left of their families.

Long before the war began, long before we could imagine what was just around the corner, we started working on a Passover episode that told the story of a small group of Israelis who – more than half a century ago – experienced their own exodus from Egypt, their own journey from captivity to freedom. We sat on this piece for a long time, since – with all that has transpired since October 7th, it accrued painful layers of meaning we could have never anticipated. And today, with both sadness and hope, we share it with you. Our producer Mitch Ginsburg will take it from here.

News Broadcast: [In Hebrew] It is 11:10. A Red Cross plane brings twenty-seven prisoners of war back to Israel.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): It’s November 16th, 1973, and we’re at the military section of the Lod airport. Among many generals and dignitaries milling around the tarmac are Prime Minister Golda Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan. It is – after all – a celebratory day, the first bit of good news since the end of the Yom Kippur War three weeks earlier. But there’s also a palpable sense of anxiety in the air. Dayan, whose hands are stuffed deep in his pockets, is pacing back and forth. Dado, the commander of the army, is chain-smoking. And Golda – in a dark, navy dress and single strand of pearls – is cupping her face in her right palm. They all look tense, but there’s something particularly anguished in Golda’s gaze. As if she’s the only one who knows, the only one who fully realizes that the momentary joy will soon be streaked with sorrow.

[Snippet of archival tape]

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Soon a red-and-white DC-6 passenger plane lands, and out of it comes a stream of young men. They walk down the stairs in striped pajamas, wide eyes and matted hair. Some of them look dazed. Lost. These are the fresh POWs, the ones who were captured during the Yom Kippur War, the previous month. But then, alongside them, is another group. Well-groomed, well-dressed…

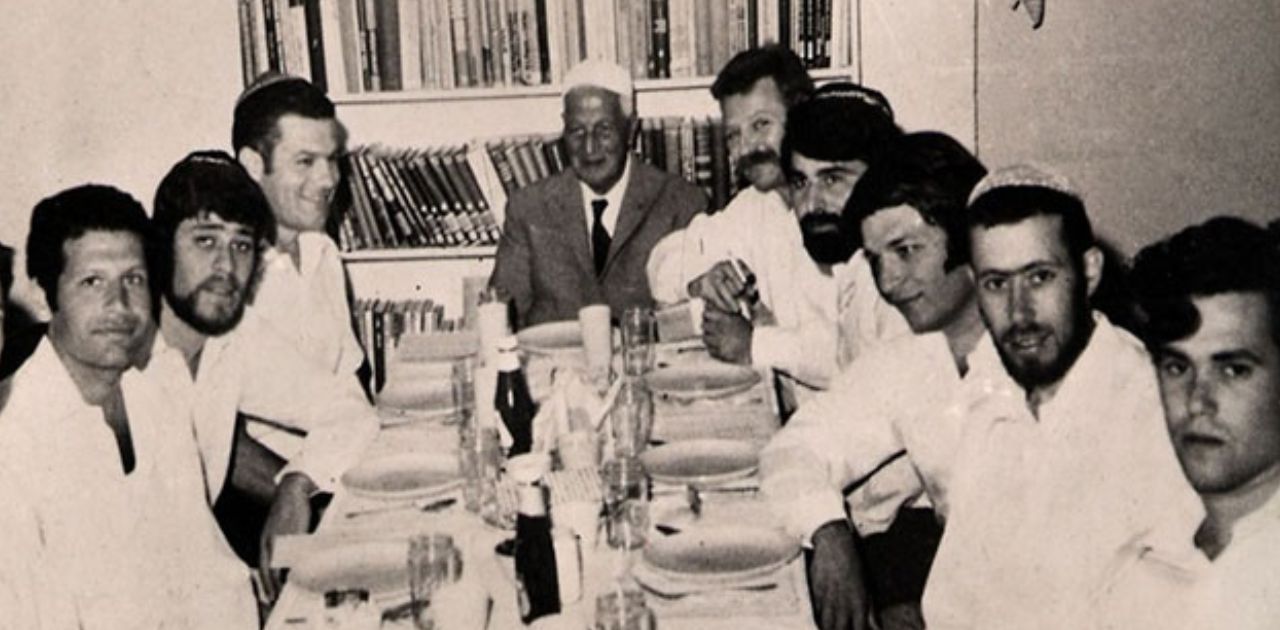

Jeff Peer: Yeah, we had white shirts and pants and the fashion of the day, our hair was… pretty long.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The guys in this group most definitely do not look disheveled. One of them is carefully carrying an architectural model made out of matches, another has his arm around General Ezer Weizman, the former commander of the Air Force, and a third, sporting stylish sideburns, is clutching a bouquet of flowers in his left hand. Together, they look more like they’re on their way to a wedding than returning from a forty-month-long stint of captivity.

Jeff Peer: It was important for us to present a picture that not only gave us satisfaction, but that would show others that you could go through this kind of a… ordeal and stay OK. Come out of it the other side.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): That’s Itzhak, or Jeff, Peer, one of those dashing POWs.

Esther Eini: I saw him coming in.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): And that’s Esther Eini, the wife of Menachem Eini, another one of the returning soldiers.

Esther Eini: He looked to me like a movie star.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Menachem and Jeff were two of the ten men known collectively as shvuyey milhemet hahatasha or “the POWs of the War of Attrition.” They were a motley crew, really: Six airmen, two infantry soldiers and two canteen workers. They had been captured in separate incidents, but all of them had been held – most of the time together – in an Egyptian prison for more than three-and-a-half years.

[Snippet of archival tape]

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Their return was emotional, both for the country as a whole and – of course – for the men themselves. Some of them felt at home as soon as they stepped into their wives’ open arms.

Esther Eini: He was smiling, was happy. And then he sawed me and we run one to the other, the children after me. We hugged and then he looked at the children, he took them on his hand.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): For others the exhilaration would soon be overshadowed by devastating news.

Jeff Peer: We went through very difficult times together and, ahhh… it’s not something I need or want to dwell on. And I think seeing and talking with people there’s always the possibility of delving into things that, uh, I don’t really want to bring up at this point.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): But we’ll get to all that in good time. For now, I want to draw your attention to a small, tattered bag Menachem Eini is holding.

Esther Eini: Very cheap looking. And terrible. So opposite to his love of fine things. You must understand, Menachem is a feinschmecker. So to come back with a shmatte [laughter] it was funny to look.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Funny perhaps, but that brown knapsack actually held a treasure. A manuscript that would make these men and their unlikely story momentarily famous: A Hebrew translation of The Hobbit. It was the fruit of their communal work during the years in which they were held in one of Egypt’s most notorious dungeons. And as a translator myself, it’s the reason I’ve always been drawn to their story. I view their achievement in a golden light – salvation through translation.

Ever since I first learned of this saga, I’ve thought a lot about J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy world and the reprieve it must have granted these men as they waited out the endless hours and days in the depths of Cairo’s Abbasiya Prison. Tolkien himself, like our captives in Egypt, was plucked from his Oxford shire and dropped into the theater of war. World War I, that is. For them it was the sands dunes of the Sinai, for him – more than half-a-century earlier – it was the mud, blood, and mustard gas of the French trenches. For both, home was beyond reach, and the sacrifice must have felt infinite.

J.R.R. Tolkien: Stories, practically always are human stories, practically always about one thing, aren’t they? Death!

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): And when it was finally time to be released, the return – for both our men and for Tolkien – was laden with the irony of real life. That’s the raw material from which The Hobbit was forged.

The Hobbit: Across this bridge the elves thrust their prisoners, but Bilbo hesitated in the rear. He did not at all like the look of the cavern mouth, and he only made up his mind not to desert his friends just in time to scuttle over at the heels of the last elves, before the great gates of the king closed behind them with a clang.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): And that’s what makes these two tales – that of The Hobbit and that of its unusual translation – somewhat alike. Both are tales of adventure and terror, bravery and betrayal, and, above all else, the things that ordinary men are sometimes called to do.

The Hobbit: I am looking for someone to share in an adventure that I am arranging. And it’s very difficult to find anyone. I should think so, in these parts. We are plain quiet folk and have no use for adventures. Nasty, disturbing, uncomfortable things. Make you late for dinner. I can’t think what anybody sees in them.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): In the 1967 Six Day War, the IDF conquered the Sinai Peninsula, a vast track of desert which was almost three times the size of the entire State of Israel. For most Israelis the period following the dramatic victory was a euphoric and peaceful time. But while the city-dwellers in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv were going to discos and schmoozing at cafés, the IDF was engaged in an exhausting war of attrition along its southern border. As the poet Haim Gouri succinctly put it, “Tel Aviv is alight while across the Canal they fight.” And indeed, Israeli military outposts were soon created in the Sinai and thousands of soldiers were deployed to man and protect them. There was, for years, a seemingly never-ending series of clashes, skirmishes and bombardments, leading to some 400 casualties on the Israeli side and thousands on the Egyptian side.

Of the ten Israeli prisoners of war held in Egypt, the first to fall into captivity was Captain Dan Avidan. This was on December 14th, 1969, as the War of Attrition, which didn’t yet have a name, had just begun. Avidan, a 37-year-old reservist and father of three, was on his way back to his outpost along the Suez Canal, when his jeep was ambushed by Egyptian commandos. Two of the soldiers that were with him were killed on the spot. Dan was severely injured. His legs were shattered by bullets, and when the enemy reached him, he simply raised his arms and surrendered his weapon.

Seven weeks later, on February 9th, 1970, a newly-married Mirage pilot by the name of Avinoam Kaldes, was locked in a dogfight high up in the skies above Sinai. He managed to shoot down two enemy MiGs, but the second one exploded right beside him, and Avinaom was forced to bail over Egyptian soil. On the ground he was picked up by two armed farmers and taken to the mukhtar, or leader, of the village. For a short while he managed to pretend to be a Russian pilot but when an Israeli Air Force chopper approached for an attempted rescue, the charade was up. Avinoam was handed off to the police, and was swiftly and brutally imprisoned.

Two days after that, it was Motti Babler’s turn. A love-struck 24-year-old, he had found himself in the Sinai almost by chance. All he wanted, really, was to start a family.

Motti Babler: A friend of mine came to me and said, “listen Motti, I know you want to get married, you and Yaffa. So come work with us in Sinai. You’ll get 1000 Liras a month! And you won’t spend a dime there because you won’t be in the city. You’ll save up and within a year, tops, you’ll be able to buy an apartment and get married.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Motti’s job was to be a ‘shekemist’ – driving a mobile canteen between the IDF outposts, selling soldiers little tastes of home – bamba, tempo Cola, Sano soap.

Motti Babler: So sababa, I went down there and worked. And I actually really liked the job. I’d pull up at the army’s outposts, and the soldiers were always so thrilled to see me. Let’s put it this way – if at that very moment God himself would have shown up, the soldiers would have been less interested in him than in my canteen.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Motti’s comparison of his work to the Divine notwithstanding, in the hierarchy of army roles, being a shekemist carries very little glory. They are not combat soldiers, and basically stand at the bottom of the military pecking order.

But on that fateful February day in 1970, Motti, and his fellow canteenman (also named Motti by the way) decided, on the spur of the moment, to ignore their commanding officer’s directive: Instead of taking a circuitous inland route, they opted for the shortcut to an outpost known as Zahava, alongside the Suez Canal. The week had been heavy with bombardments, and the route was considered dangerous, but the two Mottis wanted to make it to their destination on time. They drove the truck down the dusty desert road, taking in the tranquil waters of the Canal, and humming along with the tunes on the radio. Between them they had a single rifle, which – incidentally – was tucked away and out of reach.

Motti Babler: And I remember that I lit myself a cigarette, leaned back and just then, suddenly, a rocket hit the road right in front of our truck, and the whole road sort of blew up in our faces.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Surprisingly, Motti wasn’t overly perturbed. He instructed the other Motti, who was on his first day on the job, to jump. The two bailed out of the moving canteen, tumbling in the soft sand. Once they looked up, Motti realized two things: that the other Motti had been shot in the shoulder, and that…

Motti Babler: There was a live grenade right next to us. I looked at it, and the first thought I had was, ‘whoa, a grenade. I better pick it up and throw it as far as possible.’ Things came into focus. Seemed crystal clear. And every second felt like an hour in my mind.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Just as Motti realized what was going on, he saw a group of Egyptian soldiers running their way, their bayonets pointed straight at them. He considered pulling the safety pin out of the grenade and letting the chips fall where they may, but an Egyptian commando was quicker to the punch. He kicked the grenade out of reach and pummeled Motti. Soon enough, the two shekemistim found themselves being marched down the sloping sand to the water’s edge.

Motti Babler: We reached the Suez Canal and the truth is that I still didn’t grasp I was being taken into captivity.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The Egyptian soldiers threw them into rubber rafts and began heading to the other bank. Once they made it to the Egyptian side…

Motti Babler: My eyes went black. There were like 30 or 40 Egyptian villagers – just regular farmers from the area – who began running towards us. They were all yelling, “Alla is Great, Alla is Great,” and holding pitchforks and hoes. So I said to myself, “here we go, there’s going to be a lynch here. I’m going to die. That’s it.” When the first one of them got close enough he tried to bring down his shovel on my head. But I somehow managed to move my head enough so he hit my arm instead. And just then I heard a shot ring out. The officer of the Egyptian soldiers who had kidnapped us had shot the farmer in the leg and all the other ones started running away in the other direction. A military truck showed up, they loaded us on the truck and we drove off.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): They didn’t know it, of course, but the two Mottis were also on their way to Cairo’s infamous Abbasiya Prison.

As the frequency of these incidents along the Canal increased, a more high-stakes battle – at least strategically – was taking place way up in the sky. And if the shekemist was at the bottom of the military pyramid, at the very top stood the IDF fighter pilot.

Jeff Peer: I don’t know how to describe it. It’s a sense of freedom, a sense of being one with a machine. Uh, I always was able to fly airplanes naturally, I didn’t have to think about what I’m doing and that’s what I love, always loved about flying.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Throughout the War of Attrition, fighter pilots like American-born Jeff Peer were busy conducting recurring missions into enemy territory.

In late June 1970, four-and-a-half months after the two Mottis were ambushed and abducted, Jeff was on the runway of the Hatzor Airbase in the front seat of an F-4 Phantom aircraft. He was awaiting his turn to take off and participate in a wave of strikes against Egypt’s new air defense batteries, supplied to them by the Soviets.

Rami Harpaz: And since the Egyptian Air Force knew that they didn’t stand a chance against the Israeli Air Force, they invested heavily in developing their anti-aircraft capacities. So very quickly it became a showdown between our Air Force and their anti-aircraft missiles.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): That’s pilot Rami Harpaz, another hero of our story. Rami passed away in 2019, so I’ll be using recordings of him recounting his story to an audience of high schoolers shortly before he died. Anyway, Rami and Jeff were both part of the same mission that day – Rami took off in the first wave, Jeff was scheduled to be in the second.

Rami Harpaz: We were a formation of six Phantom planes heading southwest in a 220 direction. We were flying at a low altitude, and there was complete electronic silence – no radio, no radar, nothing – so they won’t be able to detect us. We were flying low over the sea, nearly skimming the waves. We crossed the beaches of Sinai over the Bardawil, hit the Suez Canal, and continued on to the Kotomiya Airfield, where the Egyptians had just installed three new missile batteries.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): As they neared their mark, Rami pulled up, rose to 20,000 feet, and dropped into a dive.

Rami Harpaz: You point the nose of the plane towards the target, set your sights on the target, and then you have exactly six seconds to stabilize and pull the trigger, letting the bomb loose. Once that’s done, you pull away, and then look down to see the target blazing. Then you’re flying over the horizon and you’re on your way home.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): But sixty seconds into Rami’s retreat, his back-seater reported…

Rami Harpaz: “Ne’ulim aleinu.” They’re locked on us. I looked at the radar and saw incoming missiles heading our way.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Rami took a deep breath, waited patiently until the missile was close, and then – at the very last second – jammed the stick with all his might, causing the plane to dive violently.

Rami Harpaz: But the problem is they knew this trick too.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): So as soon as he came out of the maneuver…

Rami Harpaz: And whoever wants to know what it feels like, just imagine you’re in a train going 100 kilometers an hour crashing into a concrete wall. That’s more or less what it feels like.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The missile tore off the Phantom’s tail.

Rami Harpaz: And if you’ve ever made a paper airplane during a boring class at school, you know that a plane without a tail does not fly. And well… a metal plane without a tail? Does not fly either.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Rami and his back-seat weapons system officer ejected at 14,000 feet. Floating down to the ground, he spoke into his radio: “I’m sorry,” he said. “We were hit and had to bail. I’ll try to hide in the hills to the northeast, till you come rescue me.”

Listening in to that ominous message was Jeff – in his own cockpit – waiting for takeoff on the runway.

Jeff Peer: So I said to my back-seater, “well, this is going to be an interesting flight.”

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Despite the news of Rami’s plane having just been hit, they took off. And sure enough, within minutes…

Jeff Peer: We saw two missiles coming at us, I tried to maneuver the airplane and both missiles exploded near the airplane. The airplane was damaged but I managed to release my bombs on the target that I was assigned and now I’m trying to get back east of the Suez Canal with a damaged airplane. I’m flying at about 11,000 feet as fast as I can, one engine’s on fire. And the other engine is making bad sounds. At that time, my wingman – who had observed all of this and he was flying below us – noticed another missile coming at us, and the missile exploded, apparently, right next to the airplane and severed the tail section. Amazingly, the communication within the airplane still worked. I still could talk to my backseater. And I told him to prepare to eject and initiated the ejection sequence. The F-4 has two separate canopies. So the backseater’s canopy left the airplane and I saw in the mirror and felt his ejection seat go. And supposedly three-quarters-of-a-second after that, my seat is supposed to fire automatically and to eject me from the front seat.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): That didn’t happen.

Jeff Peer: And I remember in training that they said that three-quarters-of-a-second can seem like a lifetime. And I remember thinking to myself that if I can think these thoughts it’s much more than three-quarters-of-a-second.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Jeff came tumbling through the cloud cover, still strapped to a plummeting, flaming airplane.

Jeff Peer: So it turned out that my seat was damaged by the explosion of the missiles, and it did not function. So making an interesting story shorter, I was able to manually just open the canopy and jump out the side of the airplane which was spinning in the air and found myself very very low.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Somehow he managed to open the parachute.

Jeff Peer: I was in the air for about a second under the parachute before I hit the ground, and found myself as a visitor in Egypt.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Jeff knew he was in dire straits.

Jeff Peer: They had seen the airplane fall and very quickly, I noticed a truck full of Egyptian army people driving over the… the sand dunes in my direction. And well, the somewhat, in retrospect, humorous side of this was I started to run, they saw me and they came to about a hundred or two hundred meters from me and all the soldiers got out and started shooting at me. And I remember thinking to myself that I’m a pretty good shot with a… with a rifle (I was at the time) and I can’t hit a moving target at two hundred meters. So I just kept running. And I heard the bullets and all that and like in the Western movies, and they got back on their truck and drove again but again stopped a couple hundred meters from me and started shooting again. And I kept running and finally they figured out that this is not going to work for them and they kept driving. So as I saw them closing in on me, I… I had an emergency radio that pilots have to facilitate being rescued. And I said, “I can’t defeat the whole Egyptian army by myself. So I’m going to have to surrender.” And I thought I was going to be killed. So I put the radio on the ground and tried to destroy it with whatever means I had and raised my hands and was taken as a POW, not in a very nice way.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): As had happened in Motti’s case, only the intervention of the commanding Egyptian officer saved Jeff from being lynched.

Jeff Peer: Which I had fully expected to happen. Now I can say that in a sort of easy going way right now, but obviously I was pretty scared.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Jeff too was taken into captivity in Cairo. Two-and-a-half weeks later, on Friday, July 17th 1970, Menachem Eini – a fellow Air Force officer – invited his friend, colleague and commander Shmuel Chetz over for Shabbat dinner. Esther Eini, Menachem’s wife, recalls a tense atmosphere that evening. She also remembers the way Menachem, rather atypically, insisted on bathing their two daughters and brushing their hair at length before dinner. But that’s not all she remembers.

Esther Eini: He somehow felt it is the last night and he really wanted very much to leave me with the best feeling a woman can… How would I say? He did everything in his imagination that can make me happy at that night. And it was so. All the time, I was with this last unbelievable night of love.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): They only fell asleep with first light. But when Esther woke up, several hours later, Menachem was no longer by her side. He’d been called up to fly on a mission. This was, in no way, out of the ordinary. For more than a year, Menachem, Chetz and the other pilots had been flying nearly daily combat sorties, working, as he once remarked, “like slaves.”

But as this grueling routine had become the norm, Esther spent a lazy Saturday with a friend, another pilot’s wife, at the beach. At noon, they saw a formation of Phantom F-4s scream by carrying a heavy load. She looked up and whispered a silent prayer.

Esther Eini: We came back quite late from the sea. No call, no call. I was cleaning the children, I was washing the bathing suits. Five o’clock – he didn’t call. I became worried. And then, a knock on my door.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): It was the commander of the base.

Esther Eini: He was white and shaking. I looked at him and I knew – something happened. I didn’t know what happened, but I was afraid and my heart closed.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The commander looked at Esther and said…

Esther Eini: Menachem and Chetz, his partner, their airplane was shot down. Chetz he… was killed. Menachem is alive. Very wounded, but he is alive.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The Air Force knew this to be true because Eini had spent his last moments as a free man radioing another pilot who participated in the same mission and hadn’t been hit. “I’m surrounded,” he said, as the Egyptian soldiers closed in on him, “see you soon, and send regards at home.”

Esther stood at the door staring at the bearer of this horrible news. Her two daughters both leapt from the bath and ran to the door still wrapped in their towels…

Esther Eini: What’s happening, what’s happening?

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): But Esther – who was born as Fira Khadorkovskaya in the middle of World War II, and had survived the war stashed away in an Uzbeki village and then in a Polish orphanage – kept her cool.

Esther Eini: And then I knew, how I will react and explain to them, this will be the main behavior of their life. So I didn’t cry. I kneeled on my knees. I looked at their eyes. And I said, very calm, “the plane of Abba was shot down. Abba is a prisoner of war. We will not see him for a long time. But we will continue with our life. Nothing is changed in your life. Everything will be for us the same except that we will not see our father.”

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Menachem, who was born in Iraq, is 87 now. And even though more than fifty years have passed since he returned from captivity, he still refuses to talk about his time in Egypt. In fact, not once since his return in 1973 has he sat down with his wife – his own wife – and shared tales of that period. And perhaps that helps explain Esther’s own urge to explore the details of her husband’s incarceration. When I arrived at their gorgeous home in the village of Karmei Yosef, she told me that she feels that her ability to talk about the ordeal is also, somehow, helpful to him.

Esther Eini: I must show you… [laughs].

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): She took me down to the basement, where – in a reddish trunk – she keeps all the material related to Menachem’s “shevi,” or captivity.

Esther Eini: This is the… everything that is connected with the shevi. All this are letters.

Mitch Ginsburg: Oh wow, those are his letters from captivity?

Esther Eini: From Menachem.

Mitch Ginsburg: From the prison?

Esther Eini: Yes. From the prison. Let me see a moment. I must… These are all the prisoners.

Mitch Ginsburg: That’s the day they came home, right?

Esther Eini: And this are the women.

Mitch Ginsburg: Oh, I need to see that in the light. Where are you?

Esther Eini: This.

Mitch Ginsburg: Beautiful!

Esther Eini: Ya! I was also a feinschmeker [laughter].

Mitch Ginsburg: It’s a bit of a cowboy outfit you have on there.

Esther Eini: Yeah, it was in the desert, so I had to… Oh! Look at this one. I want you to see. This I discovered, I was going to die. Since the first day, he wrote a diary!

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Esther took out a yellowing piece of paper. On it – in shaky handwriting – was written the date, July 18th, 1970, and under it – only one word.

Esther Eini: Hatchalah. The beginning.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The next page also contained just a single word, as did the next, and the next, and the next. During those early weeks all he was capable of doing was inking out one word per day, and all of them were written with his left hand, as his right, dominant, hand, had been badly injured.

As it turned out, the fact that Menachem had been severely wounded was oddly fortuitous. He was held, alone, in a hospital ward for twelve long months. And though he was interrogated at length, the questioning was largely without violence, given his condition. Dan Avidan, Avinoam Kaldes, the two Mottis, Rami, Jeff and the others weren’t as lucky.

Motti Babler: The questioning started. ‘Who are you?’ ‘What are you?’ And I pretended I was some sort of Rambo.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Motti, the canteen driver, again.

Motti Babler: I just told the interrogators my name. And that’s it. I said “I have nothing else to tell you. That’s the truth. I just sell candies.” And they said, “OK, fine, we’ll see. And then two soldiers came into the room with a metal rod. My hands and feet were shackled and they slid the rod in between my arms and my feet and they hung me upside down like a cluster of grapes.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): When I asked Jeff about the first months of his captivity, he refused to go into it. All he would say was…

Jeff Peer: There were times during the first period of being a POW, where I would have preferred to be dead.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The men – everyone that is, except for Menachem – were kept in solitary confinement in dark, two-by-three meter, cells, handcuffed almost all of the time, deprived of food and water and beaten repeatedly.

Jeff Peer: One of the crew members that was captured, was in a cell not far from mine. He was a very young back-seater, who went through some very hard physical times, and was ultimately killed during his interrogation period in Egypt.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): That man was Lieutenant Moshe Goldwasser, a fellow Air Force navigator, whose plane was shot down in August 1970. And what Jeff is delicately saying is that he remembers hearing him being tortured to death.

With time, however, the harsh treatment subsided. By early 1971, the Israeli prisoners were freed from their solitary confinement, and brought together in a relatively large cell with an outside courtyard.

Jeff Peer: It was one of the happiest moments I could imagine. My blindfold being removed and finding myself in a room with seven other people at the same time – others were brought there after me. So it was a feeling of great relief. I certainly felt that I now had a chance of getting out of this alive.

*****

Mishy Harman (narration): And we’re back. So we’re in the middle of the story of shvuey milhemet hahatasha, the POWs of the War of Attrition – ten Israeli soldiers who were captured by Egyptian forces in a series of separate incidents in 1969 and 1970. Just before the break we heard how – after a long period of harsh investigations, torture and solitary confinement – the Israeli soldiers were placed, together, in a cell in Cairo’s Abbasiya Prison. Mitch Ginsburg will pick it up from there.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Though they now all shared a cell and – seemingly – a common fate, the men had come from notably different backgrounds. Among them were kibbutznikim and city folk; tzabarim born in Israel and olim from Iraq, Argentina, and the United States; Ashkenazim and Mizrachim. Some had served together for years and knew each other well, while others were complete strangers. They were all IDF soldiers, of course, but having all emerged from independent interrogations, they didn’t know who had said what, and just how open and honest they could be with each other.

Over the last two years, I’ve spoken to almost all those who are still alive, and to family members of those who have passed away. And though the physical conditions of the cell at Abbasiya Prison represented a marked improvement over solitary confinement, every single one of them described a gnawing, ever-present and unbearable angst. There was no end in sight, and they assumed that their limitless and bleak horizon would be broken only by another war, or (and this seemed much less likely in the early 70s) a peace agreement.

And yet, despite the overarching despair, they quickly made a decision that would alter their entire experience of captivity. They wouldn’t just keep calm, carry on, and ride out the daily grind. Instead, they would… thrive. But how?

Jeff Peer: All of us, very quickly, decided that a military structure within our environment was not the best way to keep everybody happy.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Pilot Rami Harpaz, a Major at the time, was the ranking officer in the group. Perhaps it was his kibbutz upbringing, or maybe his exceptionally high EQ, but Rami realized that imposing a military hierarchy would be ill-suited for their situation. Instead, and in stark contrast to what was practiced, say, at the Hanoi Hilton where soldiers like John McCain used a tap-code system to pass orders along the chain of command, he helped establish a different, more communal, model.

Jeff Peer: So it was very much a kibbutz.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Every Friday night they would light a single Shabbat candle and gather around for a weekly meeting. At first, the candle was an improvised cotton wick stuck into a hole they punched in an oily sardine can. With time, once they began receiving visits from the Red Cross, they got real candles and an array of other supplies. But no matter what type of candles they lit, the weekly meetings were what was truly holy. For 139 Friday nights in a row they met and voted on the issues of the day.

Rami Harpaz: How should we celebrate the holidays? What should we ask for from the Red Cross?

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): That, again, is Rami Harpaz.

Rami Harpaz: What should our daily routine be? Who should be in charge of what? What should we name the cats? All sorts of things we could decide.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Gradually their conditions improved. They received pre-packaged food and money to spend at the prison canteen. A record player and books. Even a ping-pong table.

Soon, the lights within the cell were left to their discretion, and they were allowed to take care of a couple of stray cats in the courtyard.

The decisions were all made collectively. One man, one vote.

They decided to try their hand at group therapy, formed a chess league, and read literature aloud once a week.

But while all this quasi-communist camaraderie was going on, Menachem, Esther’s husband, was still hospitalized, disconnected from his fellow POWs.

Esther Eini: Shalom to my cute wife.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): This is Esther reading from Menachem’s first letter home, dated September 23rd, 1970, two months into his captivity. Though he was still writing with his left hand, the penmanship is already clearer and steadier.

Esther Eini: Last week I got your first two letters and of course I was very happy, but also disappointed. Happy because these were your letters from our home. Disappointed because the letters were old. I hope with time to receive the letters in chronological order. Today I got a letter from 29.8 which gives the impression that you are being restricted in the number of words you are allowed to write. Otherwise why the emphatic brevity?

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): He went on to give her instructions about care-packages and the way they should be sent. No perishables, he wrote, and…

Esther Eini: If almonds, then in a box and not a plastic bag. And my greatest request from you is books. Send many and only very good ones (English is fine too). I want “Chayei Adam” by Shalom Aleichem and other fine books of your choosing.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): He then signed it, as he would all his subsequent letters…

Esther Eini: Abba. He’s always signing Abba. He’s Abba of the children, he is Abba of me.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): And to a large extent, he brought that paternalistic attitude with him to Abbasiya Prison, when he was finally released from the hospital and united with the other Israeli POWs. And though everyone was obviously delighted to see him alive, his arrival upset the gentle balance of power the prison commune had created. The minutes of the July 16th, 1971, meeting give a sense of this turmoil.

Archival Tape: Meeting Number 21 – Menachem arrived yesterday from the hospital, after a year there. Our newest member is a master of wonderful ideas, who, during his convalescence, has had all the time in the world to think. So he is the originator of all the proposals tonight. The others must be burned out already. Here he comes!

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The “here he comes!” was written in English and adorned with an exclamation mark. And the “has had all the time in the world to think” seems, at least to me, like a reminder to Menachem, that – unlike him – they did not spend the last year in a pristine hospital room with white sheets, relatively good medical care and a large window.

I might be reading too much into it, but Menachem himself attested that he was, quote, “like a spoon that stirs the tea.” And that spoon clanged against the cup. Often.

The cup being, more than anyone else, the only other person in the cell with his same rank – Rami Harpaz.

Esther Eini: There was on one side, Rami – everyone is the same, everyone has the same right to decide. On the other hand was Menachem. He said, “but some of us have better decisions than others. So how we’ll be sure that the best decision is taken and not because of the popularity of someone of us?” Because Menachem was very not popular in the group.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): But this clash of cultures and personalities didn’t stop Menachem from hitting the ground running. He had no patience for the prevailing egalitarian atmosphere and wanted to run the show his way. From now on, he said, he wanted days to have a clear structure and schedule, and time to be well spent.

Motti Babler: Menachem changed a lot of things in the room. He demanded that we make a proper table for the room, so we did. He demanded that we organize meals, classes, exercise sessions, and we obeyed. All of that can be chalked up in his favor. It all came from him, and I’m grateful for that. I really am. But I have to say – to my great regret – that when it comes to interpersonal relations, to just regular human skills, he’s got nothing. Really close to zero.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): But Menachem was seemingly unfazed by his apparent lack of popularity. He was way more interested in simply getting things done. Within a few days he had devised a mandatory study schedule for the group. Menachem himself, a Technion graduate with a degree in aeronautics, would teach a daily course in advanced math and physics. Rami would teach trigonometry and mechanics. Another prisoner, the Mirage pilot Avinoam Kaldes, would teach Bible, and Jeff would teach two levels of English classes – “advanced” and “more advanced.” The initial resistance to this scholastic regimen soon dissipated, and ultimately an equilibrium was reached between Menachem’s top-down leadership style and Rami’s kumbaya-like communal one.

And between these two shepherds, the flock kept itself busy. Very busy. They sewed dresses for their daughters back home, they carved little statues out of soap bars, and they designed – and built – a folding table that could both seat all ten of them, and be easily stored away when not in use. Before they knew it, they got into a groove of impressive productivity. For Motti Babler, the shekemist, this productivity went in an… unlikely direction.

Motti Babler: My friend Jeff, or Yitzhak, Peer, the pilot, had a brother who lived in America. And that brother used to send him Playboy magazines.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): And Motti, it seems, was drawn to the, um, arts and design section (yes, apparently that’s a thing…). Anyway, one day, he told me…

Motti Babler: I saw a picture of a really unusual house in one of the Playboys. It was a German house, and I decided I just had to build a replica, or a model, of that house.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Not having much to work with, he fashioned himself into something of a match maverick. Rami – the trigonometry teacher – took care of calculating the scale, the Red Cross helped procure glue, and everyone else bartered with the prison guards for matches. Several months later, Motti had completed a perfect replica of the humble Playboy abode. He then moved on to an even more ambitious project – a miniature Eiffel Tower.

But the most lasting legacy of these captives’ incredible ingenuity didn’t come from porn magazines. It came from books.

Jeff Peer: In one of the first few boxes of books that we received, that we were able to get, were all three books of The Lord of the Rings. And I devoured them. Tolkien’s trilogy was a perfect book to send to a POW. Very well defined good and evil, hardships, you know, and it was a great escape from the physical environment that we were in.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Jeff, who had received the books in a package sent by his brother, decided that he’d share some of this much-cherished escapism with his fellow soldiers during his daily English classes.

It’s a bit stereotypical, but most of the Air Force captives were avid readers. All told, by the time they left their cell, they had amassed a library of some three thousand books. But none had a grip on the group like Tolkien’s tales. They were passed around among those who could read the books in their original English, and then discussed and dissected at length.

Jeff Peer: The others in the room who were not able to read those books as fluently as we were and to get the understanding and the enjoyment that we got out of them, asked us about these stories. And we started to tell them a little bit in our Friday night meetings – we had storytime or something of that nature where we would tell a part of the book.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The first book of the Lord of the Ring trilogy often mentions the prelude to the series, The Hobbit, which the group did not have. Jeff – via the Red Cross – asked his brother to send it to them, and the entire group waited in great anticipation.

Jeff Peer: Finally The Hobbit arrived.

The Hobbit: In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat. It was a hobbit hole, and that means comfort.

Jeff Peer: Ahhh, I read it first and then gave it to the others to read. And there were so many questions by the group about The Hobbit that we decided that it would only be fair if we translated it so everybody could enjoy this book.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Translating can be solitary and grueling work. The initial process of transferring the text from one language to another – before the joy of trying to make it sing – often feels to me like field labor: repetitive and dull, the rows so long there’s seemingly no end in sight.

But the process the prisoners came up with – none of them of course had any training in the art of translation – was different: Creative and collaborative, democratic and thorough. Translating in Abbasiya Prison was more like the study of Talmud – done in pairs, much-discussed, and capable of creating its own glow.

Jeff Peer: And the way it happened was that Avi and I would go outside when we were allowed into the outside area, alone, camp out on the sand, next to a wall somewhere, and I would read the book in English and do a simultaneous translation into Hebrew.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): As Jeff read and translated The Hobbit into his colloquial Hebrew, Avi, or Avinoam Kaldes, would ask clarifying questions and jot everything down in his perfect hand. The pale blue Egyptian notebook would then be passed on to the next hevruta.

Jeff Peer: And then Rami and Menachem would take what they called Jeff’s Hebrew and translate it into real Hebrew.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The next step was reading it out loud to the group.

Jeff Peer: The polishing was done by a committee. We struggled and we had arguments and it was a… it was great way to stay as sane as we could.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): I asked Jeff to read me some of their Hebrew translation. He chose the part in which Bilbo Baggins – the Hobbit of the title – receives three riddles from a creature called Gollum. The stakes in the scene are high: Bilbo will either be set free, or else be eaten by the slimy character who rules the underground lake in the cavern of the goblins.

I don’t know why Jeff chose that particular passage –perhaps because of the elegance of the Hebrew translation–but I do know that the last of the three riddles Bilbo was asked was brutally relevant to a group of POWs sitting and translating in captivity. Here’s J.R.R. Tolkien himself asking the hardest of the riddles:

J.R.R. Tolkien: This thing all things devours:

Birds, beasts, trees, flowers;

Gnaws iron, bites steel;

Grinds hard stones to meal;

Slays king, ruins town,

And beats high mountain down.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The answer, as Bilbo managed to guess, to what gnaws iron and grinds hard stones to meal, is, well…

J.R.R. Tolkien: Time! Time!

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Time. The endless expanse of time, which was really the only thing the men in prison had in abundance. And it ate at them like acid.

Amia Lieblich: Even a person who is in jail and know that he is going to be in jail for ten years, time passes. And he gets closer and closer to reaching his aim of freedom. They didn’t have it.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): That’s Professor Amia Lieblich, a psychologist who wrote a book, Seasons of Captivity, about this group of POWs. In it she describes how the translation operation became central to their communal activities in prison, and occupied them for months.

But after they completed the translation, something surprising happened: The group, very much guided by Rami’s sense of equality, simply decided to stop.

Amia Lieblich: Because they felt that it created two groups.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): See, the literary project inadvertently managed to upset the gentle equilibrium of the commune. Some – like Jeff – were absolutely integral to its success, while those with limited knowledge of English, Motti for example, felt left out.

So once the manuscript was done, a Friday night group decision was taken not to press on to the Lord of the Rings trilogy or to any other translation work for that matter.

Instead, they went back to playing bridge and baking cakes. Feeding the cats and fighting over which music to play.

Time passed and their Hobbit hole became increasingly cozy. At a certain point they even got a TV. And they went on yearning for home, just like Bilbo, who is described late in the book as “aching in his bones for the homeward journey.”

The 6th of October, 1973, was Yom Kippur, and the men – none of them particularly observant – were watching Flipper the Dolphin on TV. Suddenly, an Arabic news broadcast broke in. Menachem Eini, who’d lived in Baghdad till the age of ten, translated for the group. “War,” they were saying on TV, “had broken out with Israel.”

Motti Babler: That very morning the prison guards separated us into isolated cells, that way if Israeli forces somehow tried to stage an operation to release us, they wouldn’t find us all together.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): A few nerve-wracking days later, they were reunited, and the Deputy Commander of the jail himself showed up to announce that…

Motti Babler: The Egyptian Army is already at the gates of Ashdod, and will soon march into Tel-Aviv. The whole country is about to be conquered.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): While they had no way of knowing for sure, the group assumed this was nonsense. Some recall their neighbor relaying reports from the BBC; others say they heard news broadcasts in Hebrew. But what they all remember is that the next few weeks were jarring and bizarre. On the one hand, they heard the agony of the fresh Israeli POWs – captured during the war – being tortured down the hall; and on the other, they continued with their routine, the re-design of their bathroom, installing new ceramic tiles and a brand new sink. And while Rami, for instance, worried terribly about his wife’s brother and his cousin – both of whom were pilots, and both of whom (though Rami didn’t know it) had indeed been killed during the war – he knew immediately, as did the rest of the group, that when the fighting was over, a prisoner swap might be in the cards. And then, one day, it happened.

Motti Babler: They ordered us to get our things together, and that’s when we understood that the end was – finally – near.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): There were fierce debates about what to pack, what to leave behind and where to hide the precious manuscript, in case it wasn’t allowed out. Some insisted that the cats should also come home with them, including the one they aptly named Bilbo.

They divvied up the vinyl records, decided to leave the remaining contents of their care-packages for the Egyptian wardens, and boxed up the entire library.

On November 16th, 1973, the day they had been dreaming of for years finally arrived. The War of Attrition POWs were loaded onto minibuses, and taken to a nearby airfield, where they – together with some new POWs who had been captured the previous month – boarded a Red Cross plane. Some were carrying handwritten manuscripts, others handcrafted architectural models, and all were bearing deep emotional baggage, much of which would never be unpacked.

News Broadcast: [In Hebrew] It is 11:10. A Red Cross plane brings twenty-seven prisoners of war back to Israel.

Esther Eini: And then I saw him coming in. And he looked to me like a movie star. He was smiling, was happy. And then he sawed me and we run one to the other, the children after me. We hugged and then he looked at the children, he took them on his hand.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): But this Hollywood-like ending, Esther – Menachem’s wife – remembers, was short-lived.

Esther Eini: We were standing one minute hugging each other with the children. Then came Raffi Har-Lev.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): The Commander of the Hatzor Airbase interrupted the family bliss, and said…

Esther Eini: “Menachem, I am sorry, but father of Chetz is here, he insisted to come, maybe there will be a miracle and his son will come also. Can you please go to him and tell him that Chetz is dead?”

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Standing alongside the excited families, was the father of Shmulik Chetz, Menachem’s front-seater, who had been killed when their plane was hit three-and-a-half years earlier. Because the body had never been recovered, Chetz’s father held out hope against all hope, and thus showed up – uninvited – to the airbase, wishing to see his son get off the plane with the rest of the prisoners. Menachem disengaged from his wife’s embrace, stepped off to the side and gave the devastated elderly man a first-hand account of his son’s last moments.

Esther Eini: And then he came back. He was so sad, we even couldn’t hug anymore. He was so, so sad.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): But within a matter of days, Menachem was – seemingly, at least – back to his old self. He started flying again, and was bursting with energy and a zest for life – eager to pick up both his job and his social life where they’d been left off. On the home front, however, things were different.

Esther and the girls had also gone through hell during his captivity. A different hell, for sure, but for 1,217 days they had been anxiously waiting for him to return, not knowing if it would ever happen. That entire time Esther had taken care of the kids by herself, and they had grown up with an absent father. But now that he was finally back, she felt like he took it all for granted.

Esther Eini: It was terrible. I was crying all the time. And then one day he said to me, “you know, it’s difficult for me to come every day from Tel Aviv to Hatzor. Maybe I will rent a room in Tel Aviv, and I will not come every day” [laughs].

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): For Esther, who to this day isn’t sure if that meant he just wanted more space or was having an affair, this was the last straw.

Esther Eini: When I’m feel terrible I need to go to wash myself, ambatia. I said, “rega.” I went to the ambatia and I cried. I came out of the ambatia and I said, “if you rent a room in Tel Aviv, you take all of your belongings, and never never come back to this family.”

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Menachem, it turns out, was lucky. He came back to a partner who not only loved him, but was also strong enough to knock him back to his senses. Today, more than fifty-one years later, the two are still happily married.

Others, however, weren’t so fortunate. Jeff’s wife had also shown up at the airfield to celebrate her husband’s return. But unlike Esther, she was harboring a jagged secret. A week later, when they were lying in bed, she confessed to Jeff that she was in love with another man.

In fact, she had wanted to tell him in real time, in a letter to the Abbasiya Prison. But the Air Force brass forbade it, fearing it would break Jeff’s spirit.

Jeff consented to our interview on condition that I not ask about that part of the story. And indeed, I didn’t. So all I can share is what he told psychologist Amia Lieblich, in one of the interviews she conducted for her book about the ordeal. What hurt him most, he revealed, was that everyone on the airbase knew about the affair and had seen it unfold in real time. And that meanwhile he, during those long years of captivity, had been yearning to return to a home-life that no longer existed.

Right after his return, the Air Force sent Jeff and his family to a post in the United States. The idea was to put an ocean between his wife and her lover. But one month into their stay in America, on his first birthday as a liberated man, Jeff found a letter from the other man in their mailbox. From there the path to divorce was short. Jeff stayed in the States, made an illustrious career as a test pilot and instructor, had two more children, and today lives in Colorado with his third wife.

Jeff’s ex-wife, who returned to Israel with their two daughters and whose name I’ll leave out of this story, refused my request for an interview.

Rami Harpaz, who had introduced and championed the egalitarian atmosphere in the cell, returned to his military life immediately. He requested what was considered to be a cushy posting, training Skyhawk pilots deep in the Sinai desert – a job that allowed him to spend a lot of time with his kids. He ultimately rose through the ranks and became the Commander of the Ramat David Airbase. Years later, Rami and his wife Nurit co-wrote a book called The Captive and the Captive’s Wife, and he spoke to countless groups of teens and soldiers about his experience. It was, he would frequently say, his way of proving to himself that his time in the torture chambers and prison cells of Abbasiya had not been for nothing.

As you might recall, Motti Babler had gone to Sinai to make some money so that he could marry his sweetheart, Yaffa. He never imagined that the path to that wedding would include almost four years in an Egyptian prison. But to his delight, Yaffa had waited for him, and the two picked up where they’d left off. In March 1974 – four months after his return – they got married, and have since raised three kids and many grandkids. But Motti came back with severe PTSD, a definition that didn’t even exist at the time.

Looking back, he now says, he could feel it as soon as he returned, at that festive reception at the Lod airport. When a friend lifted him up on his shoulders like a returning hero, Motti begged to be put back down on the ground. But the truth is that he never fully landed. He had a hard time reintegrating into society, and couldn’t keep a steady job. There were periods in which he was so poor, he wasn’t able to put food on the table. And in many ways, the troubles never ceased.

Motti Babler: I have all kinds of problems that follow me in life ever since my time in captivity. Gastro issues, but also mental health issues too. You want me to tell you they’re all gone? They aren’t. It sticks to you, it enters your soul, right here, for the rest of your life. It’s just like the guys who went through the Holocaust. People always say “why do the Holocaust survivors just sit there and don’t talk or anything?” Well… it’s things that just… It’s a trauma that will never let go of you. Should I say that I don’t dream at night about being back in captivity? I do. In the early years I’d dream that they were coming for my kids. To take them away. And all sorts of dreams like that haunted me. What can I say? It stays with you your whole life. Nothing you can do about it.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): It took decades until he was fully recognized as a wounded IDF veteran, compensated accordingly and offered treatment, which has proved to be highly effective.

Throughout it all, he never stopped building elaborate structures out of matches. He’s made dozens and dozens of miniature models, but of course the one he created in prison occupies a special place in his heart.

Back in November 1973, when the POWs landed in Israel, Motti – all flustered and excited – actually forgot the model on the aircraft. But Prime Minister Golda Meir, who had boarded the plane to greet them, spotted the replica and like a responsible mother, asked who it belonged to, making sure nobody left anything behind.

Today, that match-house model is on display at the Rabin Center in Tel Aviv. Motti asked that we meet there, so he could show it to me.

Motti Babler: Look, this is the famous house which I built. The German house I saw in the Playboy magazine. These are all Egyptian matches. When I built it in captivity, I also made little pieces of furniture for the inside rooms. There was a kitchen, a living room, a TV, bedrooms, there was all of that inside, really really small. But the furniture all got ruined in all the balagan and bouncing around.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): And somehow it’s that description – of all the miniature replicas of everything that make a home a home – that has stayed with me.

Because when I think of the ordeal that all these men endured, I don’t think of their prison cell – its three-thousand books all stacked in neat piles, a giant folding table pressed against the wall, and the fiery Friday night votes they took on the trivial matters of daily life.

Instead, I think of Motti – yearning so hard for hearth and home, that his imagination was seized not by the pin-ups in the glossy Playboys, but by a quaint country house in one of its articles.

And I think – of course – of the poor and brave Israeli hostages, kept somewhere nearby and yet still beyond our reach. Like so many others here and around the world, I pray that they, like Bilbo Baggins, will find their way back home.

“As all things come to an end,” Tolkien wrote in the final chapter of The Hobbit, “a day came at last when they were in sight of the country where Bilbo had been born and bred. Where the shapes of the land and of the trees were as well known to him as his hands and toes. Coming to a rise he could see his own Hill in the distance, and he stopped suddenly and said…”

The Hobbit: Roads go ever on and on,

Under rock and under tree.

By caves where never sun had shone,By streams that never find the sea;

Over snow by winter sown,

And through the merry flowers of June,

Over grass and over stone,

And under mountains in the moon.

Roads go ever ever on,

Under cloud and under star,

Yet feet that wandering have gone,

Turn at last to home afar.

Eyes that fire and sword have seen,And horror in the halls of stone,

Look at last on meadows green,

And trees and hills they long have known.

The end song is Avarnu et Paro, Naavor Gam et Zeh (“We Outlasted Pharoah, We’ll Outlast This Too,”) by Meir Ariel.