Much has been said, over the last twenty-seven years, about the Oslo Accords, the set of agreements – brokered in complete secrecy in Scandinavia – that were meant to pave the way to a permanent peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians. Countless books and articles have been written, TV specials and movies have been produced, and even a Tony Award-winning play, Oslo, was staged. Yet none of these accounts mentioned David Ben Shabat, a man whose story is, in surprising ways, completely intertwined with those accords that put the Middle East on an entirely new trajectory.

Born in 1963 into what was only half-jokingly known as a “mixed marriage,” David was – almost – the right man at the right time. Long before the term “impact investment” was ever coined, David dreamed up a revolutionary idea to collect private and public investments and provide seed funding for businesses jointly run by Arabs and Jews. Prime Minister Itzhak Rabin was on board. So was Palestinian leader Faisel Husseini. And they were not alone: François Mitterrand, Henry Kissinger, Abdullah Nimar Darwish and many other public intellectuals, diplomats, politicians and business tycoons were all enthusiastic supporters of David’s innovative “Shem Fund.”

David was on his way to become a household name, the father of the world’s first peace fund, a conflict resolution guru.

But none of that happened.

Nowadays, David and his wife Tali live in Har Amasa, at the edge of the desert and just south of the West Bank. But he isn’t bitter, nor does his story end in defeat. After all, what kind of a prophet would he be if he just gave up?

If governments didn’t believe that peace would come through grassroots business partnerships, David would turn his own life into a proof-of-concept of his now defunct multi-billion dollar dream.

Skyler Inman has been interviewing David for over a year. She has heard him talk about a joint Semitic identity, about linguistic affinities, about the distant past and the far-away future. But most of all, she has heard why this veteran visionary is still unwaveringly hopeful.

And, if you want to check out David’s various products and projects (including a dreamer’s sublime tchina, or tahini), go to the Shem Rivers website.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): In early February – long before any of us could imagine how much the entire world was about to change – our producer Skyler Inman went to record an interview at one of Israel’s most iconic sites.

Skyler Inman (narration): Right, it was a sunny day – height of winter, though you’d never guess it – and I got off of the 444 bus at the foot of Masada.

Mishy Harman (narration): OK, and can you set the scene for us?

Skyler Inman (narration): Yeah, well, the birds were chirping, and since this was all pre-corona, the parking lot was packed with visitors clambering in and out of humming tourist buses. I, on the other hand, wasn’t there to see Masada. I was there to speak to a man called David Ben Shabat.

Mishy Harman (narration): And by then, you’d been recording him for quite a while.

Skyler Inman (narration): Yup.

Mishy Harman (narration): Talking about identity, roots, conflict, the land, the deep past, the far away future, and… also a lot about peace.

Skyler Inman (narration): A lot about peace.

Mishy Harman (narration): Which, at least at Masada, is a bit ironic, no?

Skyler Inman (narration): Yeah [Skyler laughs]. I mean it was at Masada, almost two thousand years ago, that a group of zealot Jews killed themselves instead of surrendering to Roman forces.

Mishy Harman (narration): Right, the famous story that every single visitor hears.

Skyler Inman (narration): Exactly. And basically there are two ways of interpreting that story – it’s either a heroic fight against oppression and assimilation, or else it’s a cautionary tale about extremism and the dangers of refusing to compromise. But, either way, there’s essentially no version of the story in which Masada tells a tale of peace.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yeah. So why were you meeting David there?

Skyler Inman (narration): David worked there, at the Dead Sea Research Institute – their offices are at Masada. He was actually the director of the Institute, and the room he sat in was labeled “The Center for Regional Thinking.”

Mishy Harman (narration): Hmmm. Can you describe him?

Skyler Inman (narration): Sure. So close your eyes and imagine a biblical prophet.

Mishy Harman (narration): OK, you mean like Jeremiah or Isaiah or Amos.

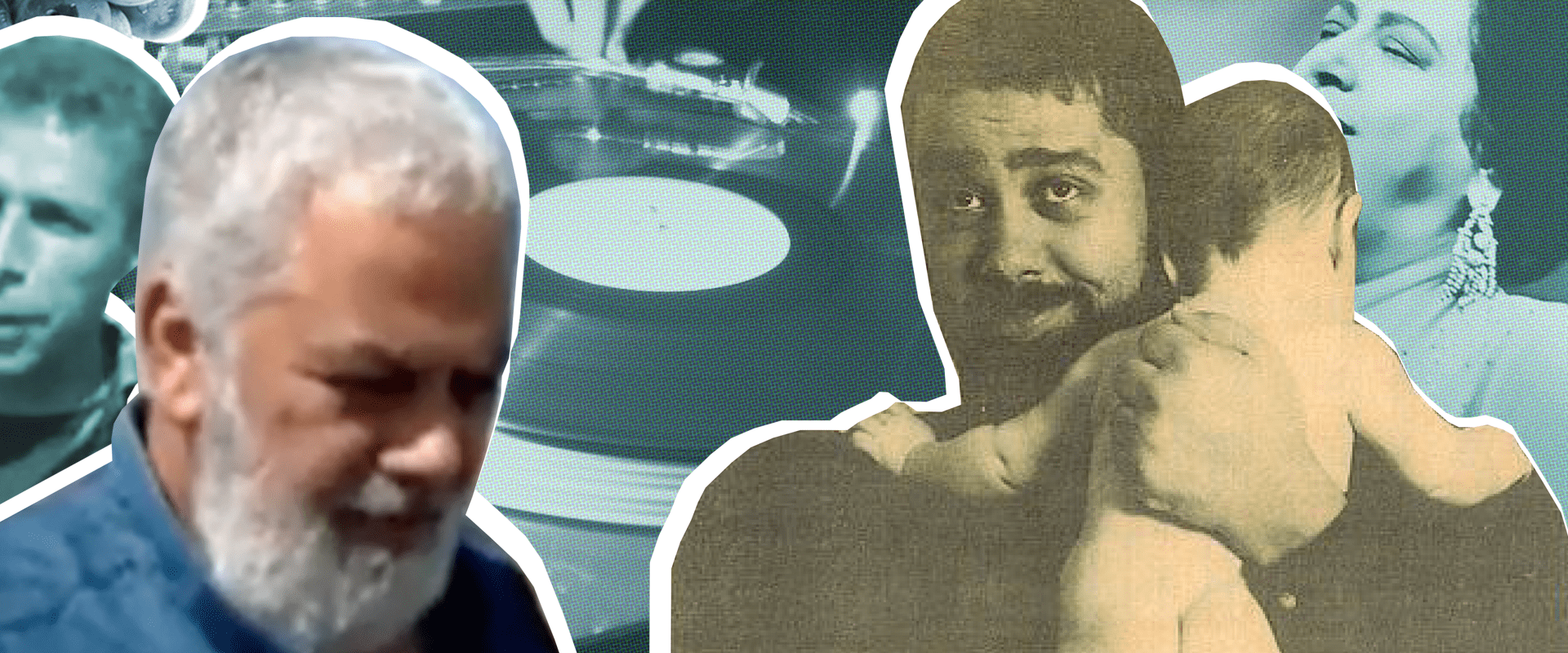

Skyler Inman (narration): Exactly. So David’s tall, has these broad shoulders, a thick white beard and unusually heavy brows that sort of make him look permanently serious, even when he’s joking around with you.

Mishy Harman (narration): And it’s not just that he looks like a prophet, he sort of talks like one, too, right with this kind of deep booming voice?

Skyler Inman (narration): Totally. Even when you ask him some completely straightforward question.

Mishy Harman (narration): Like ‘what did you have for breakfast?’

Skyler Inman (narration): [Laughing] Sure, like ‘what did you have for breakfast?’ He’ll answer in this epic, sweeping way, traveling through time and space to connect modern topics with ancient texts, referencing history and archaeology and linguistics and philosophy. Sometimes it’s enough to make you feel a little dizzy.

Mishy Harman (narration): Can you give an example?

Skyler Inman (narration): Of course. Like this:

David Ben Shabat: If you noticed, we’re all talking language, and about language. It is very… it’s a tough one. You know, language is the way your mind works, even when you’re not talking. I’m going out of my body and I’m trying to see ‘how is my mind wired?’

Skyler Inman (narration): Or this…

David Ben Shabat: The Hebrew language was the protocol that actually kept the Jewish people in all time of Diaspora. They had a network – a global network – of communities that actually functioned as the Internet of our time.

Mishy Harman (narration): [Laughs].

Skyler Inman (narration): But, just so you know, David actually hates the word “prophet.”

Mishy Harman (narration): Oh, how come?

Skyler Inman (narration): He thinks the word sort of embodies what he calls an “end of days” mentality, as in – if there’s a prophet, then there’s an inevitable fate that we’re heading towards. For him, it kind of removes the importance of individual choice and action. And he’s all about the power of small, everyday interactions. Regular people changing history.

Mishy Harman (narration): Among many other things, Skyler was there to talk to David about a brief moment in time that could have been a turning point, both for David himself, and the country as a whole. A moment that in some ways is entirely forgotten, and in others is ever-present, even today.

The Oslo Accords.

Mishy Harman (narration): The set of agreements that was meant to pave the way to a permanent peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians. Now, so much has been said and written about the Oslo Accords over the years, that it’s easy to forget what that period actually felt like. All the drama, the revelation that these secret back-channel negotiations had been going on for months in Scandinavia, the speculations, the newspaper headlines, the rumors of a new Middle East, the public ceremonies, the signing, the hopeful rallies, the violent protests. In many ways, these events put us on an entirely new trajectory, one that led us to where we are now.

I was ten when Rabin and Arafat shook hands on the White House lawn. And I remember it well. We were all glued to the TV. Both my parents had tears of disbelief in their eyes. And, of course, I remember them teary-eyed once again, two years later, when they came into my room to tell me that Rabin had been assassinated in Tel Aviv. So that whole period looms large in my life.

These are some of my clearest, most vivid, memories. Over the years those memories have been augmented by books and articles I’ve read, by films and TV specials and even a Tony-winning Broadway play I saw. So I thought I knew quite a lot about Oslo.

Yet none of those books or films mentioned David. A man whose own story is, in surprising ways, completely intertwined with that of the Oslo Accords. But long before any of that happened, he was just a regular kid, born – in 1963 – into what was only half-jokingly known as a ‘mixed marriage.’

David Ben Shabat: My dear late father Moshe was born in Mogador in Morocco, and my mother was born in Iraq. Very close to old Babylon, to the famous grave of the prophet Ezekiel. They met in Israel.

Mishy Harman (narration): Skyler Inman will take it from here.

Skyler Inman (narration): David’s parents were both native Arabic speakers. But they spoke different dialects, so…

David Ben Shabat: They couldn’t talk Arabic in house. They just talk Hebrew.

Skyler Inman (narration): David grew up in Ramat HaSharon. It wasn’t far from Tel Aviv’s hustle and bustle, but it might as well have been a different galaxy. The defining memories of his early childhood were strawberry fields, orange groves and the smell of cow manure mixed with rich soil.

It was the late sixties, and Israel was still adjusting to two major developments: First, over the preceding two decades, the country had absorbed nearly 1.5 million Jewish immigrants, roughly half of whom – called Mizrahim – came from the Arabic-speaking countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

By the time David was born, the Jewish population of Israel was the largest and most diverse it had ever been. And as vibrant as this was, it was also a massive challenge. Israel’s economy was struggling to accommodate the rapid population growth, and for much of the 1950s, the government imposed strict rations.

Then, during the Six Day War, in June 1967, Israel overtook the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank of the Jordan River, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. Overnight, the country had tripled in size and found itself in control of a vast Palestinian population. And yet, as this sea of identities and allegiances stormed around him, David’s early childhood took place in relative calm.

He grew up in Morasha, a neighborhood in Eastern Ramat HaSharon, where most of his neighbors were Mizrachi Jewish families that, just like his own, looked and sounded Arab.

David Ben Shabat: I had the chance to feel, you know, that I am part of a tribe.

Skyler Inman (narration): At the end of the sixth grade, David graduated from his predominantly Mizrachi elementary school – which, by the way, was named after one of the most famous Mizrachim of the day, the Egyptian-Israeli spy, Eli Cohen. He entered middle school, and it was there that he learned a new word:

David Ben Shabat: Integratzia, integration. And when you’re saying, “integrated, integratzia” you’re going to the dictionary because we didn’t had Google there and you are searching what is integration?

Skyler Inman (narration): At the time, Ramat HaSharon was one of a handful of Israeli municipalities piloting a new policy of educational integration. And integration – as Yossi Dahan, an education policy researcher, explained to me – had two main goals. Number one…

Yossi Dahan: Narrowing the inequalities between Mizrachim and Ashkenazim. And the second is cultural integration.

Skyler Inman (narration): This was how David and his friends from the neighborhood first met the “other” Ramat HaSharon kids. Kids who came from Ashkenazi, European families.

Yossi Dahan: Integration is really the child of a larger idea, which is the melting pot.

Skyler Inman (narration): The melting pot. By bringing together children of different backgrounds into the same classroom, policymakers hoped to create a more culturally-cohesive generation of Israelis.

David Ben Shabat: They located the school right in the border between East Ramat HaSharon and West Ramat HaSharon.

Skyler Inman (narration): David immediately noticed differences. Kids from the other side of town ate different foods, listened to different music, and had parents with different accents. All that was fine, of course. An exciting part of the whole integration scheme. But it didn’t take long before he understood that the two worlds weren’t being integrated in an equal fashion.

Shortly after the start of the school year, David’s teachers announced that they would be dividing the students into levels A, B, C, and D – indicating their academic strength. Except, curiously, there was no formal evaluation.

Of the approximately four hundred kids in David’s class at Alumim Middle School, half were from his Mizrachi neighborhood. But of those two hundred or so seventh graders, only a handful – two or three, including David – were placed in the most advanced “Group A.”

Though the Ministry of Education did have guidelines for testing and placement, Yossi – the educational expert – told me that teacher bias was widespread.

Yossi Dahan: Most of the time, it’s up to the teachers. You know who is a high achiever and who is a low achiever, and you just split them.

Skyler Inman (narration): In fact, this bias was noticeable enough to have a name.

Yossi Dahan: Segregation within the integration.

Skyler Inman (narration): David was just twelve. But he felt, instinctively, that something was wrong.

David Ben Shabat: They just placed people that came with me together from the elementary school, in the second, third, fourth group.

Skyler Inman (narration): Among those students banished to the lower group levels was David’s best friend, Ezra Shalom. Unlike David, who grew up in a Hebrew-speaking household, Ezra’s parents spoke Arabic at home. So his Hebrew was inflected with Arabic tones and Iraqi slang. And that’s how Ezra, formerly known as a bright student and a math whiz, ended up in Group C.

David Ben Shabat: I was amazed. I was so amazed that after the second month in this school, I wrote a letter.

Skyler Inman (narration): David sent his letter to the local Ramat HaSharon newspaper, and – to his utter surprise – it was published. The following morning, the irate school principal marched into David’s classroom, paper in hand, and demanded an explanation.

David Ben Shabat: She came to my class. She was very furious. I remember her words: “Give us a chance! We are a new school.”

Skyler Inman (narration): But David – all of twelve years old, I’ll remind you – didn’t feel like there was time to ‘give it a chance.’ And he was proven right: The following year, his friend Ezra dropped out of school and found a job working construction.

David Ben Shabat: He felt that he is treated like an imbecile and he was not an imbecile.

Skyler Inman (narration): Though he was often vocal about it, things didn’t really change. Year after year, class after class, David saw in his teachers’ eyes a dismissiveness of, sometimes even a repulsion towards, the culture and mindset of his Mizrachi peers.

Yossi Dahan: Part of the melting pot was to modernize Mizrachi Jews.

Skyler Inman (narration): Yossi Dahan, again.

Yossi Dahan: And how to modernize them is basically they have to discard their history and culture. And this was part of the idea of integration as well.

Skyler Inman (narration): In high school, when David and his classmates were taught Jewish history, they learned about Herzl and Weizmann, not the sages of Babylon or Ibn Ezra. And that, according to Yossi, was no accident.

Yossi Dahan: There is an intervening variable, which is the Arab, OK? So Mizrachim are basically Arabs.

Skyler Inman (narration): The conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors, Yossi says, sent a clear message: “Israeli” and “Arab” were mutually exclusive categories. If you wanted to be Israeli, then any trace of Arab culture should be rejected, washed out, and left behind.

Yossi Dahan: The tragedy is that the Mizrachim themselves, some of them, internalized this.

Skyler Inman (narration): But not young David. After all, he thought to himself, he was Israeli. His mother tongue was Hebrew and he knew that just as soon as he finished high school he’d go serve in the IDF. How much more Israeli can you be?

At the same time, he also knew that his ancestors had lived in, and been a part of, the Arab world for millennia. And that was part of him, too.

So he really was, deep down, an Israeli-Arab. For him, there was nothing contradictory about those identities. They were just parts of who he was.

And the Middle East? Arabic? Arab culture? None of that was primitive, or something to be ashamed of. Quite the opposite. It was valuable. Familiar. Beautiful.

As David saw it, his teachers, the quote-unquote establishment, they were all simply scared.

David Ben Shabat: This is a very basic Zionist fear to get assimilated in the Orient.

Skyler Inman (narration): And in his friend Ezra’s story, David understood that this fear could change people’s fates, shape their futures, and limit their opportunities.

At eighteen, David was indeed drafted into the Israeli Air Force, and was stationed on a base in the West Bank. On their way to and from the base, David and his fellow soldiers would pass through Ramallah.

David Ben Shabat: I’m talking about early 80s. It was before the years of the First Intifada.

Skyler Inman (narration): Back then, Ramallah wasn’t off-limits to Israelis the way it is today. And for David, the city was a revelation. One that was at once both comforting and unsettling.

See, for years he’d been told, time and again, that Arabs were the enemy. But to him, more than anything else, Ramallah, that so-called enemy city, felt… familiar.

David Ben Shabat: It looked like, you know, part of the stories that my mother used to tell me, you know, fairy tales about how do you say it in English, you know… One thousand and one nights? Yeah. And it had this, you know, romantic atmosphere, the vibe, the smells, the nargilas.

Skyler Inman (narration): Ramallah was pulsing with Arab culture. And to David, it was like little reminders of home.

David Ben Shabat: The sole Arab identity I could recognize when I grew up was my oriental family.

Skyler Inman (narration): He heard Umm Kulthum and Abd El-Wahhab songs blasting from radios all over. The same songs David’s uncle loved to sing. And there were a million other details too, like how people would greet one another, or address the elderly, or how men were known as “Abu” – “the father of” – followed by the name of their son.

David Ben Shabat: This Abu thing, I remember from my Iraqi family of my mother. Yeah.

Skyler Inman (narration): Ramallah had this magical appeal to him. It was like a time machine that allowed him to access the stories his parents and grandparents told about the ‘old country.’ So in his off-time from the base, David became a regular in Ramallah’s coffee shops. His Arabic was rudimentary at best, but slowly and surely, he began to follow more and more of the conversations around him.

Arabic and Hebrew, he realized, had so much in common.

David Ben Shabat: These are sister languages that evolved together for more than fifteen hundred years.

Skyler Inman (narration): And though perhaps obvious or trivial, this linguistic affinity, at least to David, was proof of something. Of a similarity, a sameness, one that ran much deeper than just shared musical tastes or familial mannerisms.

As he learned to speak Arabic, he felt he was reconnecting to deep roots. And ironically, it was actually Hebrew, this newly-revived language that united Jews around the world – that was acting as his bridge back to Arabic.

The more he thought about it, the more symbolic that seemed to him. And soon enough, it began to shape David’s sense of identity.

He had to believe that over the millennia that they spent living side by side, Jews and Arabs in the Middle East had developed a common cultural DNA. Something even stronger, or more fundamental, than religion.

David Ben Shabat: The people that are speaking Hebrew and Arabic are two of a kind. You don’t have to invent something. It’s there. You just have to take the dust away and then, you see life.

Skyler Inman (narration): David began to imagine an invisible, cultural chain linking Arab Muslim to Arab Jew to European Jew. A common denominator rooted in their languages, that made all of them – David, his Moroccan father and his Iraqi mother, his Ashkenazi teachers, and the Palestinians in the Ramallah coffee shops – members of the same semitic culture.

It suddenly made so much sense to David. This was the solution that allowed him to maintain both parts of his identity. That didn’t force him to choose sides.

David Ben Shabat: I felt like, I’m whole. I am OK with both worlds.

Skyler Inman (narration): After all, if the whole idea of Zionism was that the Jewish people were returning home – why shouldn’t they feel at home? Why shouldn’t they have common cultural ground with their neighbors? They were all, originally, people of the Middle East, or as David began to call it: Eretz Shem. The region, or land, of the Semitic people.

And this semitic identity? That was common ground.

But David could also see that this similarity was lost on almost everyone around him – both Israelis and Palestinians. All anyone seemed to focus on was the one thing no one wanted to share – land.

In Ramallah, the conversations around David turned again and again to the same topic, the same source of anxiety: Israeli Settlements. And specifically nearby ones like Ofra, Beit El and Psagot.

David Ben Shabat: They saw the first time a Jewish settlement… Jewish villages coming, that in no time it receives roads and telecommunication and electricity and sewage and water.

Skyler Inman (narration): Many of these settlements seemed to have materialized overnight, and in the span of just a few years, now had better infrastructure than the surrounding Palestinian towns. The young Palestinian men David heard talking were all nervous, tense. The landscape around them was transforming – fast.

David felt the steam of rebellion gathering in Ramallah, and he reasoned that if conflict was the result of distrust and us-versus-them, then the opposite must be true as well.

That peace and cooperation were a matter of finding commonality. Of Israelis and Palestinians seeing, as he now did, just how alike their languages were, how kindred their cultures were, and how within reach a shared future could be – if they just wanted it.

David Ben Shabat: This Semitic identity – the joint identity, stemming from the similarity, the closeness, the proximity between Hebrew and Arabic – it’s something tangible to hold. And it’s a vehicle, it’s an instrument to bring better life here.

Skyler Inman (narration): But how could he get others to realize this, David wondered, when fear and distrust had folks on both sides with their finger on the trigger?

Mishy Harman (narration): And now, back to our episode.

We left off with David, an idealistic soldier serving on a base near Ramallah, trying to figure out how to spread his great, if slightly naive, revelation – that Hebrew and Arabic, Jew and Arab, Israeli and Palestinian – were all just members of one big Semitic family. But as often happens, life took over. In 1985, David moved to Tel Aviv. But he didn’t, as you might expect, sit down and write sweeping political treatises. Instead, his life took an unexpected turn.

OK, back to Skyler.

Skyler Inman (narration): David’s first job out of the army was, well… refreshingly civilian.

He opened a club.

David Ben Shabat: It was called “HaSlick Culture Club.”

Skyler Inman (narration): As surprising as this might sound, back in the mid-80s, Tel Aviv only had a handful of places where you could go out and really dance. And David wanted HaSlick to offer a little something for everyone. Sunday was jazz night, Monday was 60s rock-n’-roll, Tuesday featured Latin music, Wednesday oldies, and on and on. All quite removed from anything to do with a wide-ranging Semitic identity.

But nevertheless, HaSlick was a hit.

David Ben Shabat: It was a small one. You know, only a hundred and twenty seats. It was filled with two hundred people every night. Every night. It was a success.

Skyler Inman (narration): David had transformed an empty room and some bar stools into something people loved. And they came back, night after night. He saw, first-hand, that even a small business venture like his bar slash dance club could energize people and impact the rhythm of an entire city. For him, it was…

David Ben Shabat: Exposure to culture, exposure to the ability to change it.

Skyler Inman (narration): One day, in 1985, a man showed up at David’s door.

David Ben Shabat: In Tel Aviv people are coming, knocking your door and asking for work.

Skyler Inman (narration): The man was about the same age as David, and had a kind, quiet look about him. They started talking. His name was Hassan, he told David, and he’d come in from Gaza (in those days just a bus ride away from Tel Aviv) to look for a job. David had long dreamt of serving Middle Eastern food at the club, so basically on the spot he offered Hassan work as his cook. It was a match made in heaven.

David Ben Shabat: It was Hassan, and then he brought his brother, Ahflag, and then you know a few people from two families from Gaza.

Skyler Inman (narration): Soon, Hassan and Ahflag and David were spending every day together, often late into the night. They’d cook, clean, handle customers, and – most importantly – unwind after long shifts. David began to count these men not just as his employees, but as his friends.

And that’s when David’s almost forgotten grand theory of unity resurfaced, in the form of a little flicker of an idea.

David Ben Shabat: If I am doing something with you, together… We are coming together every morning, we are waking up and we are thinking about our joint project. We are, you know, planning. I see your mind. I see the way you think. You see mine. You can identify.

Skyler Inman (narration): What if somehow, he fantasized, it were possible to incentivize business ventures run jointly by Arabs and Jews? Businesses could bring individuals together to work towards a common goal. And when Arabs and Jews worked together – not, as was often the case, with Palestinians employed by Israeli bosses – but side by side, as equals, they could “see each other’s mind.” And that, he was sure, would reveal just how similar they really were.

David Ben Shabat: I was quite confident that this is what we need. The way to eliminate fear is just to see yourself in his personality.

Skyler Inman (narration): At this point, David’s idea was still pretty vague. But he had a feeling. A belief in the power of business and collaboration. On a micro scale, he thought, working together could build friendships between business partners. On a macro scale, it might shift the combative mentality of the entire population.

But the year was 1987, and David was just a twenty-something bar owner. He excitedly shared his idea with some friends, but like so many prophets before him, no one really wanted to listen.

So, for now at least, David set this glimmer of an idea on the shelf. He went on with his life, worked hard, dated and ultimately married Tali, a young Israeli sabra who couldn’t resist the prophetic twinkle in the eyes of the man she lovingly called Dudu.

Tali Ben Shabat: Talking about these ideas, that’s what made us stick together. It just felt right. I knew I would never be bored with Dudu.

Skyler Inman (narration): So, not quite a unified Semitic identity, or peace in the Middle East. But at least something came out of being a wide-eyed dreamer.

Anyway, the success of HaSlick pushed David into a series of… eclectic business ventures. First he became a consultant to other bars, then he tried (and failed) to bring small aviation manufacturing to Israel. He dabbled in newspaper publishing, and even worked with a chemist to market an eco-friendly mouthwash. In other words, he was what we might call today – a serial entrepreneur. David was getting by, nothing major, but enough to make a living.

It wasn’t all fun and games, though.

In the background of all this were the riots of the First Intifada. [Fade-in on protests] The pressure that David had felt building up in Ramallah during his army service had finally burst. The young men he had met in the coffee houses – along with thousands of their peers – had taken to the streets in protest. [More protests] Some threw rocks and tossed Molotov cocktails. The Israeli Army responded with a policy known as the “Iron Fist.” There were many casualties and mounting tension. In July 1989, the Islamic Jihad pulled off what is considered its first suicide attack on a civilian bus. [Sounds of report on attack]. The future looked grim.

In 1992, two events shook David’s life. In June, his father Moshe passed away, and in November his wife Tali gave birth to their first child, a son. In the span of less than half-a-year, David had lost his father and become one himself. And this was a wake-up call.

David Ben Shabat: It certainly pushed me to do things of some significance. No, not wasting time on, you know, just… making money here or pushing a project there.

Skyler Inman (narration): Once again, just like in his army days, he began asking himself these big, existential questions.

David Ben Shabat: Who am I? What am I doing here? Why? Where did I come from? Where am I going?

Skyler Inman (narration): He wanted to do something that mattered. Something that made a difference. Not just in his own life, but in the lives of the people around him. His old hint of an idea, by now covered in dust on the shelf, began to glimmer once again.

David knew that distrust and fear between Israelis and Palestinians were as high as ever. He understood that in order to get people moving, collaborating, and working together – connections that would lay the necessary foundations for a grassroots peace – there would need to be an incentive. And what incentive works better in business than an enormous pot of cash?

David dreamt up a master plan, which in the early 1990s was actually way ahead of its time. It was a large-scale, internationally-supported peace fund. Fifteen years before the term “Impact Investment” would first be coined, his idea was to collect private and public investments in order to provide seed funding for businesses jointly run by Arabs and Jews.

And David knew exactly what to call it: Keren Shem – the Semitic Fund.

For a young father like David, going all-in on a quixotic project like this – literally trying to create peace in the Middle East – was an undeniably risky move, both financially and professionally. I mean, let’s be honest – what the hell was he thinking?! His wife, Tali, told me that they knew it wouldn’t be easy.

Tali Ben Shabat: It’s living in a struggle. Nothing is stable. But I believe in what he believes in, so it makes it easier.

Skyler Inman (narration): For both David and Tali, the birth of their first son seemed like it was exactly the right motivation to try and get this fund off the ground.

Tali Ben Shabat: Dudu promised me my kids won’t have to go to the army. I was sure we would make peace by then.

Skyler Inman (narration): And so, with Tali and their baby son Mishael at his side, David began his campaign to breathe life into the Shem Fund.

Inside their small apartment, David set up a command center of sorts – a home office equipped with the most cutting-edge technologies of early 1990s Israel: An IBM desktop computer, a fax modem, and an enormous brick-shaped device known as a cellular telephone. With baby Mishael in one hand and his cell phone of roughly the same size in the other, twenty-nine-year-old David began placing unsolicited calls to the most important financial, political, and cultural figures around the world.

Skyler Inman: Why were they even picking up the phone from you, though? That’s what I wonder.

David Ben Shabat: If you are dealing with something that you are deeply convinced that it’s relevant to all of the people in the area, so I believe this power goes forward and opening doors for you. We have this saying in biblical Hebrew, “nickarim divrei emet.” Talk of truth is recognized. If you talk truth, you know genuine truth, there is something maybe in the soul of the people that you are talking with… Something that is recognizing that it is a higher truth than your personal ego.

Skyler Inman (narration): Whether these leaders were responding to David’s ‘Talk of Truth,’ or else were just curious to see what this dreamer from Tel Aviv was all about, many did indeed pick up. Among them were public intellectuals and diplomats, politicians and business tycoons. And what was even more surprising than the fact that they listened, was that they all seemed to like his idea.

The President of France, François Mitterand, expressed his support in a letter he sent via his consul in Jerusalem. Henry Kissinger agreed to be the honorary director of the fund.

On the Palestinian side, David met with people that most Israelis regarded as enemies, like Haidar Abd el-Shafi and Hanan Ashrawi. And that was a big deal at a time when meeting with members of the PLO was, officially at least, still illegal.

Skyler Inman: Were you scared to be breaking the law?

David Ben Shabat: No, I felt good. I felt, you know, that I’m doing the right thing.

Skyler Inman (narration): In East Jerusalem, David met with Faisal Husseini.

Husseini’s father, Abd al-Qader al-Husseini, had been the commander of the Arab forces during the siege of Jerusalem in 1948. Though more a politician than a military man, Faisal followed in his father’s footsteps and became one of the leaders of the Palestinian national movement.

In their meeting, he made it clear to David that he thought the Palestinian people held the true claim to the land. He pointed to a study that suggested that Palestinians were the descendents of the biblical Jebusites, a tribe that lived in Jerusalem before its conquest by another David – King David.

Our David was a bit, well… speechless.

David Ben Shabat: Thought he was kidding the first time, but he was… quite serious.

Skyler Inman (narration): But David wasn’t there to debate ancient history. For the purposes of his project, each side could keep its own narrative. The only thing that mattered was the present.

David Ben Shabat: He was a man of vision. He knew Hebrew. He knew Israeli literature.

Skyler Inman: Did you speak with him in Hebrew?

David Ben Shabat: No. In English and partially in Arabic. He had, you know, his national limits in his house. [Skyler and David laugh].

Skyler Inman (narration): After hours of conversation that began in the Iron Age and ended with dreams for the twenty-first century, it was clear that Husseini was on board, too. And he opened even further doors, allowing David to meet with other members of the Palestinian élite.

In Kfar Qasim, David sat with Sheikh Abdullah Nimar Darwish, the founder of the Islamic Movement in Israel. David and Darwish smoked hookah for hours, talking history and religion and freedom. By the end, the Sheikh, too, gave his blessing.

So for months this not-yet-thirty-year-old self-appointed peacemaker went from one high-level meeting to the next, as if he were a senior official, conducting high-stakes shuttle diplomacy. And David? He started to feel like his dream was beginning to take shape.

Tali Ben Shabat: At the beginning it was so exciting.

Skyler Inman (narration): Tali, David’s wife, once again.

Tali Ben Shabat: It was like something miraculous is going to happen, you know?

Skyler Inman (narration): On the Israeli side, David went straight to the top – to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. And as far as he knew, his Shem Fund plan was…

David Ben Shabat: The very first practical scheme that Prime Minister Rabin saw that was thinking regionally.

Skyler Inman (narration): A proposal that made peace through everyday people. Everyday life.

David Ben Shabat: And not talking about, you know, borders and lines and armies and police and guns.

Skyler Inman (narration): David wasn’t sure whether his proposal – a twenty-five-page document with some 1992 microsoft word graphics – would be taken seriously, or else tossed into the PM’s trash can. He patiently fed the document – page after page – into the fax machine and hit the “send” button. David then waited anxiously, and sure enough, three weeks later, his fax machine started screeching. [Fax screeches]

When he pulled the page out, he saw it was an official message from Eitan Haber, Rabin’s Chief-of-Staff:

“Dear Sir, The Prime Minister has received and read your proposal regarding the Shem Fund. He has ordered your proposal to be passed on to the Finance Minister and the Director of the Bank of Israel.”

And just like that, David was in! His one-man show was now on center stage. David started to imagine the future. There would still be a ton of red tape and endless meetings with government bureaucrats. But with such a clear endorsement from Rabin himself, the sky was now the limit. Somehow he, David Ben Shabat from East Ramat HaSharon, was the right man at the right time. It would be his idea, his dream that would finally bring peace to the Middle East.

A few months later, in April 1993, Globes – Israel’s largest financial publication – ran a three-page feature on the project. And there was David, in a large black and white photograph, cradling his infant son above a big, bold title: “The Shem Fund, His Three Billion Dollar Israeli-Arab Baby.”

David Ben Shabat: The project have all the blessing from the European Community, World Bank, the PLO in Tunis, and the authentic leadership of the Palestinians of East Jerusalem.

Skyler Inman (narration): And, now, of course, also the Prime Minister of the State of Israel.

David was on a roll. And there was no stopping him or his baby.

Mishy Harman (narration): So Skyler, we’ll get back to the story in just a minute, but I want to stop here for a second and ask, like, how unusual was all of this? Was it really that easy to get all these super powerful people to listen or was David just lucky?

Skyler Inman (narration): That’s a great question, and one I’ve been asking myself a lot, too. I was stunned to learn that David had cooked up this whole huge scheme – and yet, I’d never heard of it. And I mean… I studied Middle Eastern politics, and I read a lot about the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. So basically, I think the answer is that it’s a little bit of both. On the one hand, David was in the right place at the right time. The Madrid Conference, in 1991, had left this feeling of possibility in the air when it came to negotiation. But, nothing really was happening with it. Rumors had started to swirl that those negotiations were basically dead in the water. But there was still this appetite at that point in time. Peace, for a lot of people, really did feel within reach.

Mishy Harman (narration): So you’re saying that people were receptive to new ideas, and maybe that made them more willing to meet with and listen to some upstart like David?

Skyler Inman (narration): Yeah, essentially. But at the same time, it was also incredible – like almost unbelievable – that he got so much support, because he really was an outsider. I mean, here’s this thirty-year-old former club owner, who’d never been involved in politics or diplomacy or really anything relevant before. And on top of that, he was a young Mizrachi guy whose family came from Iraq and Morocco, and he was entering a playing field that was still dominated by the sort of old guard Labor Party men, almost all of whom were Ashkenazim or quintessential ‘tzabarim’ like Rabin. So there really is something special about David. He’s sort of this maverick. The kind of guy you’ll never forget, even if you meet him just briefly. He was like this fearless bulldozer. He had no limits, and was just going to do whatever it took to make his dream a reality.

Mishy Harman (narration): OK, so with that, let’s go back to our story, and to David, whose Shem Fund had just received a green light from Rabin.

Skyler Inman (narration): After the Globes article, David felt like he was the man of the hour. But even he was surprised when he received a call from Rabin’s chief partner slash nemesis.

David Ben Shabat: I was called to the Foreign Ministry and had a meeting with Shimon Peres.

Skyler Inman (narration): Now, the fierce rivalry between Rabin and Peres has been somewhat minimized in the history books. But at the time they were essentially running two parallel operations. The Prime Minister’s Office and the Foreign Ministry often learned what the other was up to from the press.

Like everyone else in the country, David knew about this bad blood from reading the papers. But he was an outsider, largely oblivious to the inner workings and intrigue of the government. And when the Foreign Minister summons you? You go, of course.

David put on a nice collared shirt, drove up to Jerusalem and gave Peres the routine pitch, laying out exactly why concerted, widespread economic investment was the right way forward. It was a spiel he had gotten down to a science by then.

David Ben Shabat: He was sitting there, you know, quiet and listening.

Skyler Inman (narration): But that’s when something odd happened. Unlike basically everyone else he had talked to, Peres didn’t seem excited or enthusiastic. Instead, he just sat there and when David finished his presentation, Peres seemed agitated. After what felt like an endless and awkward silence, Peres got up, and – though he had famously quit smoking years earlier – asked his aide for a cigarette. He then thanked David for coming and ushered him out the door.

David wasn’t sure how to read this reaction, but he wasn’t concerned. Perplexed, perhaps, but not worried.

A few weeks later, David received yet another call from the Foreign Ministry. This time, they requested that he meet with a representative from Peres’ office – a man named Amiram Magid. David assumed that Magid was a bureaucrat Peres was sending to talk over logistics. And this, he thought, was a good sign. Rabin had signed on, now Peres. Peace and prosperity felt like they were just around the corner.

David and Magid agreed to meet at a restaurant in Jerusalem, not far from the Foreign Ministry. David arrived early. He sat down and ordered lunch.

David Ben Shabat: I remember what I ate. Orez veShu’it. Rice with red beans.

Skyler Inman (narration): He was ready to dig into the details, eager to understand exactly how the Foreign Ministry would help roll out his peace fund.

David Ben Shabat: I thought that he is the… you know, the field guy to come and to help me push the project forward to maturity, with the assistance of the Foreign Ministry.

Skyler Inman (narration): But just as soon as Magid arrived and started talking, it became clear that David had misjudged the situation. All he heard Magid say was…

David Ben Shabat: Stop now. He even didn’t use the word please.

Skyler Inman (narration): Astonished and stung, David managed to mumble a meek “why?” to which Magid replied…

David Ben Shabat: I cannot tell you why.

Skyler Inman (narration): There was something authoritative about Magid’s directive. It was clear that this was coming from above, and that there was no room for negotiation. This development was staggering. A few minutes earlier David had walked into the restaurant a confident man with a multi-billion dollar plan. Now he was a guy sitting in front of a plate of rice and beans.

But David had come too far to give up without a fight. He quickly came to his senses.

David Ben Shabat: I told him “no, no way. I’m not going to stop. But thank you for your advice. I hope that the Foreign Ministry will cooperate and will assist.”

Skyler Inman (narration): On his way home, David ran a post mortem in his mind. What the hell had just happened? Had he insulted someone? Said the wrong thing? Made some kind of political faux-pas?

David Ben Shabat: You know, I was very curious what brought him to this idea that he not not only not helping me but asking me to stop.

Skyler Inman (narration): Magid hadn’t explained exactly why they needed David to pump the breaks on his project. All he said was that for now – for the next two or three months, at least – he needed to cease-and-desist.

David Ben Shabat: He gave me the feeling that I am an obstacle.

Skyler Inman (narration): Him?! An obstacle?! Till a moment ago, he was the solution! David couldn’t, for the life of him, figure out what was going on.

All David knew was that, before long, word of his failed meeting with Peres’ man Magid began to spread. He was soon notified that the Israeli Finance Minister and the Governor of the Bank of Israel were now backing out.

Even Eitan Haber, Rabin’s right-hand man and David’s point-person, started using vague language, calling the fund – the super concrete project they had been working together to implement – an “economic idea.”

None of this made any sense to David. Until it all did. See, what David had no way of knowing at the time was that Peres had seemed agitated during their meeting because his Shem Fund? Well, it hit a bit too close to home. Only a handful of people (and historians debate whether Rabin himself was among them) knew that a select team of Peres’ men were off in far-away Oslo trying to hammer out a comprehensive peace deal with their Palestinian counterparts. This had been going on for months, in total secrecy.

In the final days of August 1993, reports surfaced of a set of agreements brokered in Norway between representatives of Israel and the PLO. News of this breakthrough – soon to be known worldwide as the Oslo Accords – took everyone, including of course David, by utter surprise.

Many Israelis in what was known as mahane hashalom, the ‘peace camp,’ were ecstatic. A bright future that just yesterday had seemed impossible, was now – suddenly – within reach. Folks dreamed out loud of open borders, of regional cooperation, of ending violence.

But for David, the news was devastating. It wasn’t because he didn’t support peace. He obviously did. Nor was it because he belonged to the roughly fifty percent of the nation that saw Oslo as the end of the Zionist state. Not at all.

For him, it was personal. He understood that the Shem Fund – his world-changing, peace-creating business incubator – hadn’t just been delayed or temporarily sidelined. It had been killed.

David Ben Shabat: It all vanished.

Skyler Inman (narration): And the more he, and the rest of the world, found out about the Oslo Accords, the more they seemed like the exact opposite of his own plan.

Instead of building something from the ground up, Oslo focused on borders and authorities. It built fences where David had wanted to see bridges. It created peace between leaders, but not between peoples. And besides, all anyone could talk about was what seemed to him to be the most inane details of all.

David Ben Shabat: They were only concentrating on, you know, arranging the ceremony. And the big big question – if Rabin will shake Arafat’s hands or not. It was the only question on table. They were talking nonstop on it on the news. I was shaking my head. I didn’t understand… Is this the important issue here?

Skyler Inman (narration): Roughly two weeks later, on September 13th, 1993, Prime Minister Rabin and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat appeared on the South Lawn of the White House. And in front of rows and rows of photographers and news crews, the two men – bitter enemies for decades and decades – did indeed shake hands.

Back among his friends in Tel Aviv, David was surrounded by euphoria. It was as if the Messiah had arrived. But David was crushed.

And it wasn’t just his personal disappointment about the demise of the Shem Fund. It was because he had a sinking feeling that none of it would last.

David Ben Shabat: I had this… you know, clear sense that I remember that it will burst.

Skyler Inman (narration): In November 1995 – five weeks after a second round of agreements was signed – Rabin was assassinated.

Seven months later, Netanyahu beat Peres in the general elections and the Accords, which had been announced to so much fanfare – including the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize – ultimately stalled.

Years passed, and the list of locales in which the saga of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process unfolded grew longer and longer. Oslo led to Wye River which led to Camp David and Taba and on and on and on. In the early 2000s, the Second Intifada erupted, leading to Operation ‘Defensive Shield,’ and ultimately to the building of the Security Barrier or Separation Wall.

And throughout it all, each exploding bus, each stabbing, each bombing and each missile. Each air strike and each military operation was a searing reminder to David of the future that could have been.

If he closed his eyes, David could – like Isaiah – imagine an alternate reality in which his peace had been given a chance. A future in which, perhaps, Israelis and Palestinians would have beaten their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks.

Mishy Harman (narration): Wow Skyler, that’s a really depressing image. This devastated, bitter visionary, sort of going about life thinking, you know, “if only they had listened to me.”

Skyler Inman (narration): Totally. David’s not a very effusive or emotional human being, even after I’ve interviewed him like a dozen times. But it’s very clear how dark this period was for him. He took Oslo – and its failure – very, very personally. To him, it all felt so avoidable. Like you’re saying, you know, if only his idea had been given a chance.

But maybe even more interesting to me than all of that is that the Shem Fund was going to be David’s legacy. His contribution to Israel, to the Middle East, to mankind even. And it all vanished. Completely.

Not just in that it didn’t happen. But also, mostly, it vanished from memory.

Mishy Harman (narration): What do… what do you mean by that?

Skyler Inman (narration): Well, being a reporter, I wanted to talk to other people who had been involved in one way or another with the Shem Fund. All the people that came up in David’s story – Peres and Magid and Rabin and Haber and others. Unfortunately, many of them have since passed away. But there are quite a few who are still alive, and I spoke to almost all of them. And guess what?

Mishy Harman (narration): What?

Skyler Inman (narration): None of them remembered David or his plan.

Mishy Harman (narration): How can that be? Wasn’t the Shem Fund about to bring peace to the Middle East?

Skyler Inman (narration): Listen, I spoke to at least ten retired civil servants and former government officials who were close to Rabin, Peres or the peace process. I even eventually tracked down Amiram Magid – the man who met David at the restaurant and gave him the cease-and-desist order. And all of them claimed to have never heard of the Shem Fund. One Foriegn Ministry employee, who – at least according to David – sat in on his pitch meeting to Peres, told me that “it was a very hectic period, with hundreds of meetings, people with ideas and different projects.”

Mishy Harman (narration): I mean it’s true that it’s been twenty-seven years, but still… You’d think they’d remember, no?

Skyler Inman (narration): Yeah.

Mishy Harman (narration): Did this make you… I guess… question things?

Skyler Inman (narration): I mean, we always fact-check everything we air. And in a factual sense, David is absolutely telling the truth. He has tons of these yellowing documents packed away binders that back up what he says.

Mishy Harman (narration): Sort of the archeological record of the Shem Fund.

Skyler Inman (narration): Right. And I even managed to find a sealed file in the Israeli National Archive with David’s name on it. Not a single person had requested to see it in the past twenty-seven years, but… there it was. The archive scanned the material for me, redacted some of the details for security reasons, and after months of waiting, I finally received the contents.

Mishy Harman (narration): Wow, and what did you find out?

Skyler Inman (narration): Inside were dozens and dozens of faxes and photocopies and letters back and forth with Rabin and his Chief-of-Staff, essentially wondering what to do with this pushy young guy who wouldn’t take no for an answer.

Mishy Harman (narration): So David did meet and work with all these people.

Skyler Inman (narration): Absolutely. And for a while, at least, he even had their support. Whether or not he was as close as he felt he was to achieving peace in the Middle East… that’s another question.

Mishy Harman (narration): So, if all of that’s true… why doesn’t anyone remember him?

Skyler Inman (narration): Well, the more people I spoke to, the more I started to realize I was encountering a very basic aspect of human psychology. We tend to remember the things we take seriously. The things we find important. Like, David remembers every single detail of some of these meetings. Everything – what he wore, what was said, how people reacted. It’s frozen in time for him as if it happened yesterday. And that’s because the Shem Fund was his vision. His baby. But for everyone else who isn’t David, it just didn’t feel all that meaningful. Their baby was the Oslo Accords, and that’s what they remember.

Mishy Harman (narration): And that, I guess, is true for a lot of people – not just those who worked on the Accords, but lots of regular Israelis, too. Oslo was the defining event of that period. It eclipsed everything. Till it itself was eclipsed by an assasination, which happened – it’s hard to believe – twenty-five years ago next month.

Maybe under different circumstances – more luck, better timing – the Shem Fund would have been realized. Maybe David would have become a household name, the father of the world’s first peace fund, a conflict resolution guru, the inventor of impact investment. And maybe not.

But he isn’t bitter, and his story doesn’t end in defeat. After all, what kind of a prophet would he be if he just gave up? Here’s Skyler once more, with the coda of the story.

Skyler Inman (narration): David is nothing if not stubborn. And if the government didn’t believe that peace would come through grassroots business partnerships, he would just have to show them he was right.

His own life would become the proof of concept for his now defunct multi-billion dollar dream.

In 1997, David and Tali moved their family to Har Amasa, a remote kibbutz just outside the West Bank and not far from the South Hebron Hills. There, amidst Palestinians, Bedouins, settlers, and Israeli development towns – David intended to prove his point. To create a micro-scale Shem Fund – an Israeli-Palestinian business that would live up to the ideals of his original mission. David and his Palestinian partners produce different products – tahini, organic grape juice, clay pottery dishes, grape honey – and sell them on the Israeli market.

They call their business “Shem Rivers” – a humble reincarnation flowing from the dry river bed of the Shem Fund.

Back in August 2019 I joined him when he went to visit one of his business partners, Hisham Fakhoury, a ceramicist from Hebron. And I immediately understood what he had envisioned with the fund.

They chit-chatted only briefly about work – how the grape harvest is doing so far this season, whether the farmers are happy with the crop. And, before long, they just settled into a conversation about life.

Hisham Fakhoury (David Ben Shabat translating): He’s saying, “we want to live together and to do things together. Politics – this perception of states – has nothing to do with life.”

Skyler Inman (narration): David and Hisham drank coffee, ate grapes, and caught up on one another’s family news. They were just two friends, really, hanging out. And that, I guess, was David’s dream all along. To build real friendships through honest work.

I don’t know if history will remember David as a prophet. Probably not. And, for what it’s worth, he doesn’t waste any time trying to convince people that he is one. He just sees himself as a guy who stumbled upon a truth and wants to share it with the people.

But, come to think of it, isn’t that more or less the definition of a prophet?

And like prophets – everywhere and always – David often stands apart from the crowd. When people around him were so hopeful about Oslo, he was hopeless. And now, when it seems that so many people have lost hope, he is, somehow – and despite it all – steadfast.

David Ben Shabat: I’m full with hope. Yes. I believe that we are in the right place in time. Because people have grown… grown up. I truly believe that it’s good starting point. Be’emet. Hakol Tov. Achla?

Skyler Inman: Achla. More than achla.

Joel Shupack scored and sound-designed the episode, with original music and additional music by Blue Dot Sessions. Sela Waisblum created the mix.

Thanks to Avner Goren, Yoav Orot, Esther Werdiger, Wayne Hoffman, Sheila Lambert, Erica Frederick, Jeff Feig and Joy Levitt.

The end song, “Migdal Bavel” (‘Tower of Babylon’) is by System Ali.

Project Kesher is a non-profit organization that empowers and invests in women. They develop Jewish women leaders – and interfaith coalitions – in Belarus, Russia, Ukraine and Israel, deliver Torahs to women who’ve never held one before, broadcast women’s health information on Ukrainian Public Radio, and help Russian-speaking immigrants to Israel advocate for equal rights.