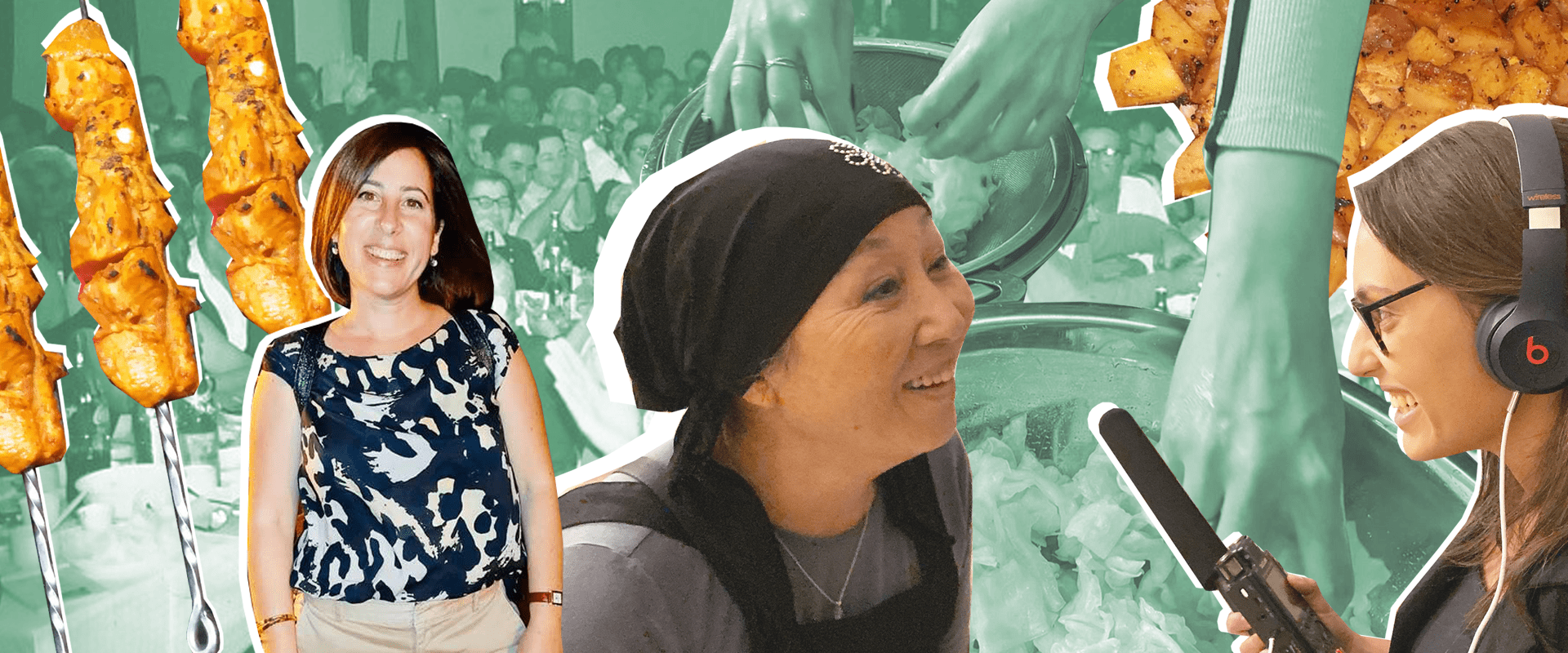

While “soul food” has come to mean a specific type of cuisine, for the women we encounter in today’s episode, there is no soul without food. Food has gotten them through marriages and divorces, it has been with them as they crossed oceans and continents, it has comforted them in times of pain and anchored them in moments of joy.

Mishy joins his 18-month-old niece, Sol, for dinner. He tries, with partial success, to find out what her favorite food is.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman: What’s your name, chuchu?

[Sol whispers]

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s my little niece, who – at just a year-and-a-half – might be a tiny bit too young for her Israel Story debut.

Mishy Harman: What are you whispering? Sol, say your name. What’s your name?

[Sol sings]

Mishy Harman (narration): Her name is Sol.

Yael Barash Harman: Say “Sol”!

Sol Harman: Mao!

Yael Barash Harman: Mao?

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Sol’s mom, Yael, my sister-in-law.

Mishy Harman: Yael, how do you spell Sol’s name?

Yael Barash Harman: S-O-L.

Mishy Harman: And why was she named Sol?

Yael Barash Harman: She was born really early in the morning, so she was… came out with the sun. And we felt she’s marking like a new day. And…

Mishy Harman: So it was Sol for the sun?

Yael Barash Harman: Sol for the sun, yes. You like your name?

Mishy Harman (narration): I joined Sol for her dinner.

Yael Barash Harman: What do you like, Sol? What do you want to eat?

Mishy Harman: Sol, what do you love to eat the most?

Sol Harman: Apple.

Mishy Harman: Apple. Do you like eating apples?

Sol Harman: Ken.

Mishy Harman: Wait, let’s get some help here from your… from your brother and sister, OK? Shaizee and Abie, what does Sol like to eat the most?

Shai Zena Harman: Cookies. Ice cream. Pasta.

Abie Harman: Pasta. Oatmeal.

Mishy Harman: Oatmeal?

Abie Harman: Yeah!

Shai Zena Harman: And very very much, bananas.

Sol Harman: Bana.

Mishy Harman: Banana?

Sol Harman: Ehh.

Mishy Harman: OK, what else?

Shai Zena Harman: Milk.

Mishy Harman: Milk? From Imma?

Shai Zena Harman: Yeah!

Mishy Harman: Or from cows?

Shai Zena Harman: From Imma!

Mishy Harman: Sol, what do you want to eat?

Yael Barash Harman: What do you want?

Sol Harman: Tzitzi.

Yael Barash Harman: That’s what she loves the most. Tzitzi.

Mishy Harman: Sol, are you drinking some milk?

Sol Harman: Ehh.

Ziporah Rothkopf: We’re ready? We’re ready? Kimchi, it’s such an art. Everybody should make their own kimchi, as they like.

Mishy Harman (narration): A few years ago we had an idea to create a four-part miniseries in the four quarters of Jerusalem’s Old City.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Red pepper powder and the fresh garlic.

Mishy Harman (narration): The miniseries itself never materialized, at least not yet, but we did come across some incredible tales. And like most good stories, they led us down winding paths, and in all kinds of unexpected directions. But none led us quite as far as this one…

Ziporah Rothkopf: It’s easy [chopping].

Mishy Harman (narration): Which starts at the Seoul House – a kosher Korean restaurant in the heart of the Jewish Quarter.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Actually that’s my favorite part of the cooking. Like a therapeutic.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Ziporah, the owner of the restaurant.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Well I have a many names. Korean name is Bung-Ja, they call me BJ. Bung-Ja means like daughter of a phoenix. So when I convert, I asked “what is bird in Hebrew?” They said, “the bird in Hebrew ze tzipor, and the female bird is tziporah.” I said “that’s my name.” So I keep all my names. So basically my legal name on passport is like a Bung-Ja Ziporah Kim Rothkopf [laughs].

Mishy Harman (narration): And if there’s one thing Bung-Ja Ziporah Kim Rothkopf loves to talk about, it’s food.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Think about it. What’s going to your mouth? You become what you eat. And when you eat good food, you’re healthy, you feel good, you know? Yeah. I think food is very important! The Korean food I don’t know whether you eat… Korean food is very different food. Very different from all other food, you know? And it’s very fermented. Takes a lot of time. My sauce takes about a year. The soy sauce. Real soy sauce is just beans with a salt and water that ferment.

Mishy Harman (narration): At first we thought this would be a sweet and curious little culinary story. But it quickly turned out to be an international tale of fate, trauma, identity and well, also…

Ziporah Rothkopf: Kimchi!

If there’s one thing Bung-Ja Ziporah Kim Rothkopf loves to discuss, it’s food. “I can leave my land,” she says, “I can leave my family. But I could never leave my food.” It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that she is the woman behind KOKO, and the owner of Seoul House – a kosher Korean restaurant in the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem’s Old City. But what Yochai Maital initially thought would be a sweet and curious culinary tale of fermented kimchi, quickly turned out to be an international saga that touches upon questions of fate, trauma and identity

Act TranscriptZiporah Rothkopf: So you gonna ask me questions or I’m just gonna talk?

Yochai Maital: Umm.. maybe take me through your day. How do you… How do you start your day?

Ziporah Rothkopf: I get up very early in the morning. I get up like four, four-thirty and then go to Kotel and then I daven with minyanim, the holy people. And the first minyan, which called the netz, yeah, that’s when Hashem is most merciful for us. And that’s where we ask requests, daven, you know, praise. And that’s how my day starts. After I finish visiting Hashem, I feel like I have done my day. And from now on, it’s all just fun, and all just a bonus day, you know? So nothing really bothers. You know what I mean? It’s a whole different headspace. When you do davening, you know, early in the morning, and you start day early, it’s like instead the life is riding you, you are riding the life.

Yochai Maital (narration): “Instead of life riding you, you are riding the life.” Ziporah told me that sentence the very first time we met, more than two years ago. And somehow, it stayed with me. I can’t get it out of my head. I keep on wondering – am I riding the life? I don’t think so. At least not like Ziporah, that’s for sure. Like most people, I’ve basically taken what life has given me. I was born into a certain family, a certain culture, a certain religion, gender, nationality – and that pretty much dictates who and what I am. But, well, that is not Ziporah’s story.

Ziporah Rothkopf: I was born in South Korea, 1947. My childhood – I was very active child, very curious, and I just wanted to find new things.

Yochai Maital: What was Korea like back then?

Ziporah Rothkopf: Well, for instance, I went to like a primary school, and each class was like eighty-five kids, and one teacher. And we can hear the pin drops. And we were very disciplined, and very clean, we cleaned our windows and floors and shiny and we cleaned our school classrooms. We were very trained.

Yochai Maital: And did you have brothers and sisters?

Ziporah Rothkopf: I had one brother who passed away several years ago, and I have six sisters, so it’s like all together seven daughters, one son. And my brother was not like a strong one. We were very strong rather, but he was a son, so he got all the special treat [laughs]. You know what I mean, it’s Korea.

Yochai Maital: No I don’t know…

Ziporah Rothkopf: Oh yeah, a lot of chauvinism. Like if you’re a woman, and end up buy a house or something, the purchase tax will be like five, six times more on women. Like discouraging women to go out. Today is different story. I am already seventy-some, so you know I talking about old, old times… And we went through tough times.

News Reel: In first pictures from Seoul, following the pre-dawn military coup that overthrew…

Ziporah Rothkopf: There’s a coup, 1960.

News Reel: Troops guard public buildings in the early hours of martial law proclaimed by the army…

Ziporah Rothkopf: And I never really knew about these things, you know? The government is seize, and military’s all over, and then fire burning in the corners, and barricades and stuff like that, I was a little kid!

News Reel: The battle against Communism and poverty.

Ziporah Rothkopf: And one day I just saw like my father – five, six people carrying him in a stretcher into the house and I found out that he almost died. They.. they beaten up so much, like he… bones all broken. And miracle that he survived. And I remember almost, almost whole year he was bed-ridden.

Yochai Maital: What about your mother?

Ziporah Rothkopf: I was very close to my mom. Yeah, she was always in my heart. She was always right there to do what she can, rather than like judging, or telling me what to do, not to do, you know? She had a belief in me. My mother was a great singer, she wanted to be a singer. But back then, when she was growing up, they don’t let their, you know, daughters to become singer, or public entertainer. It’s not respectable.

Yochai Maital: Would she sing to you?

Ziporah Rothkopf: Oh yeah, she… she actually sang like until almost till she passed away.

Yochai Maital: Can you give us just a taste?

Ziporah Rothkopf: [Ziporah sings] I have couple of things that I love to sing, yeah. Usually I don’t sing in front of men. All my sisters are great singers, and whenever I visit my sisters, and we all drink like crazy, you know beers and stuff, and then we go to karaoke and we just sing along, and dance along, and there’s nobody there, just, just girls, you know, us.

Yochai Maital (narration): By the mere fact that we met in Jerusalem’s Old City, you can already guess that Ziporah’s story is full of unexpected twists and turns. But her life actually started off in a pretty mundane – even cliché – manner. Right after high school, she went to college – where she majored in what was considered to be a respectable ‘female’ subject – home economics. And it was there, as a sophomore, that she fell in love with a college jock.

Ziporah Rothkopf: He was a quarterback in the university team for the American football. And he was very popular, six foot tall. Dream guy, you know?

Yochai Maital (narration): After graduation they got married and had two kids – a son and a daughter. Things were seemingly good. But soon cracks started forming.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Well, there are times that he would not come home.

Yochai Maital (narration): And when he would finally show up, he was always ready with a story.

Ziporah Rothkopf: “I had a fight in a market place and I ended up going to a police and then I stayed there at night,” and something like that. I wanted to believe it. And one day I wanted to really find out whether it’s true.

Yochai Maital (narration): She marched over to the local police station and asked the attending officer about the so-called “big brawl” in the market.

Ziporah Rothkopf: “No such a fight last night, in a marketplace,” you know…

Yochai Maital (narration): Her suspicions confirmed, she now had to face what was actually going on.

Ziporah Rothkopf: I felt like my foothold was just wide open, falling, and I was crying. How this life that I live is such a lie. I knew that this marriage is broken, because there’s no trust. We already had two kids and they were little babies. And, really destroyed my whole value of life. I did not want to live.

Yochai Maital (narration): For two very long years, as they were trying to negotiate the terms of their separation, the couple still lived together, sleeping in separate rooms.

Ziporah Rothkopf: And then one day, he came in and become very violent, started beating all of us. My kids were trying to… to pick up the phone in the other room. My ex just picked her up with one hand and threw her. She escaped. It was already midnight. She called my mother. So my mother came with my brother. They came and they took me away. It was very violent. He was drunk. But you know what? Now I look back, I look at it differently.

Yochai Maital: In… in what way?

Ziporah Rothkopf: Well, you hear that anybody who converts to Judaism, that they have a Jewish soul to be born with. If I had a Jewish soul, and then this is a Korean body, and I’m married to this guy, how am I ever gonna be returning to be a Jew? Really think about it. He himself is a victim in a way.

Yochai Maital: Was getting divorced shameful?

Ziporah Rothkopf: Oh yes. Big shame. I had never really failed anything. I was just very matzliach, very successful.

Yochai Maital (narration): As a divorced woman within a highly patriarchal society, she felt the entire legal system was set against her.

Ziporah Rothkopf: The guys get the kids, there’s no custody, they just take them. And then you’re at their mercy to see them. My daughter and my son were in a grip of my ex and his mother. And they would not let me see them. He said, “if you want to walk out on me, you have to walk out with nothing.” That’s how bad it became. I signed off everything to him. If that’s the only way he’s gonna let me go. When I signed it all off, I said to him, “you got all you wanted. You wanted kids, you wanted money, you wanted a house, everything. I’m starting with nothing. And you start with everything. We’ll see one day. Yeah.” I rather sell a little apple on the street, be proud to live, than living like this and lie. That’s not a place where I wanted to be. I was thirty-two years old.

Yochai Maital (narration): Not being able to see her children drove her mad.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Almost every night I used to wake up crying.

Yochai Maital (narration): In the morning, she would sneak over to their school just to get a glimpse of them through the fence.

Ziporah Rothkopf: And when they see me they would run away. They were so scared their father, then I realize this is unbearable. If I live far away, it would probably easier. They’re right here then I can’t even talk to them.

Yochai Maital (narration): In 1979, Ziporah – then still Bung-Ja, or BJ – made the impossible decision to leave Korea.

Ziporah Rothkopf: My whole family came out to the airport! All my sisters, all my brother-in-laws, my mother! Everybody, twenty some people came to the airport say goodbye! Could you believe it? The flight was like, from Seoul to New York takes about nineteen-and-a-half hours. And I did not sleep.

Yochai Maital (narration): When she landed in the US, she was penniless and alone. Not knowing what else to do, she answered a job listing in Vegas, which specifically looked for young Korean women.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Like in a way hookers, they find rich Korean gamblers. And then they recruit them to their hotel. And then they give everything free – the drink, women, the drug, who knows what… – I didn’t know any of this things. But I ended up going to the Las Vegas because this very powerful guy said he can help me with a working visa. And you know, you’re so pretty, you’re this and you’re that.

Yochai Maital (narration): She was put up in a casino hotel and quickly put to work.

Ziporah Rothkopf: I go there, and I’m finding is that these people are very weird to me. You know, this is not good for me.

Yochai Maital (narration): After just five days, she realized her mistake and tried to quit. But her boss told her that she had to settle her tab at the hotel before she could go. He knew she didn’t have any money, so he suggested an alternative. Come over to my place, he told her, clean my house and prepare a nice home-cooked Korean meal for me. Then, unsurprisingly, he casually slipped in the fact that he was ‘separated.’

Ziporah Rothkopf: I was so broken. I felt like the people can just step on me. Just because I’m a divorced and single woman. Just I’m nobody.

Yochai Maital (narration): She grabbed her few belongings and literally ran out into the desert.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Las Vegas was so dark. This was beyond MGM or something it’s like a desert. And I was crying. I said I’m gonna go back to Korea. This is not for me.

Yochai Maital (narration): She took a taxi to a dingy airport motel. The next morning, weighing her options over a tepid cup of coffee, she realized that going back wasn’t really in the cards – she didn’t have enough money for a return ticket. So instead, she opened the yellow pages and started making phone calls. To her surprise, she managed to land an interview to be a blackjack dealer at the Sahara Hotel.

Ziporah Rothkopf: They gave me audition and five guys, six guys, in front of me playing with the two deck. And I won all of them. And they said, “you’re hired!” And later on I found out that they love Korean women dealers, young. And that’s a how I got the job.

Yochai Maital (narration): Growing up in a traditional Buddhist household in Seoul, she could have never imagined that she’d end up in a smoky casino in Vegas dealing cards to inebriated clients. But she enjoyed her job, and she was good at it, too. Then, a few weeks in, she got an unexpected call. A close childhood friend from Korea had moved to New York. She was both expecting a child and getting a divorce, and she asked Bung-Ja if she might be able to come help out with the new baby. The friend was calling from a payphone so her husband wouldn’t hear. She sounded absolutely desperate.

Ziporah Rothkopf: I said to her, “stop crying, I’m coming in, I just got a new job. But I’ll tell them, there’s some family problems and I need to go take care of it. I’ll take a two weeks break. So I got tickets. And I came. I still remember I paid a $650, my money [laughs].

Yochai Maital (narration): She moved in with her friend and started helping out. One day she was in the basement, doing a load of laundry, when an orthodox Jew walked in.

Ziporah Rothkopf: With a sack of you know laundry. And I thought he was like, looks like a Jesus or somebody. I never knew about the Jewish. You know? He looked like a Jesus. He has a beard, you know, stuff like that, so I guess it’s if there’s certain first sight, you know, feelings…

Yochai: Really?

Ziporah Rothkopf: Yeah. Just a laundry room! You know like Moshe Rabbeinu, Ziporahh Imeinu, they all met at well, this like a well [laughs]. Think about it, you know, I was in my trouble.

Yochai Maital: Emm hmm.

Ziporah Rothkopf: But when I transcend from my trouble and go in to help somebody else. There Hashem is helping you. I said that all the time to people, “if you feel like you’re in trouble, OK? Look around, see who you can help.” Hashem will help you by you helping other people. That’s the my life lesson. Yeah.

Yochai Maital (narration): Bung-Ja’s original plan was to “make it” in America, and then return to Korea with enough money and stability to fight to get her kids back. Falling in love was never part of the plan. But, well…

Ziporah Rothkopf: We had amazing feelings for each other.

Yochai Maital (narration): They couldn’t have been more different. Moshe, who had just finished medical school, grew up in a religious family on the Lower East Side. And Bung-Ja? Well… Soon after that fateful laundry room meeting, she returned to the blackjack tables in Vegas. But they kept in touch, and wrote each other letters.

Ziporah Rothkopf: And one day, I’m dealing. I see this guy sitting there. It’s Moshe sitting there in Las Vegas, in my table, with a hundred dollars. I said, “what are you doing here?” I said, “you’re not gonna have that hundred dollars in five minutes, you know? Stop playing! Go away from my table!”

Yochai Maital (narration): An invisible force was at play. Stronger than both of them, stronger than their upbringing. Stronger than thousands of years of halachic tradition.

Ziporah Rothkopf: So we had a romance and we started being serious. And it wasn’t… it wasn’t that simple because I was a non-Jew and his… his parents are survivors. His mom is from Auschwitz. She had a two sons and husband and they all perished. His father from Buchenwald. And they had a scars.

Yochai Maital (narration): Moshe’s parents simply weren’t able to accept his choice.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Parents disowned him. They schlep him to, you know, big ravs and rebbes and they try to bribe him.

Yochai Maital (narration): But in many ways these difficulties actually brought Bung-Ja and Moshe closer together.

Ziporah Rothkopf: One of the reason that I really loved him is because the way that he dealt with his parents. You know, his parents were off the wall. His mother will come to his examining room – no appointments – with a knife on her… her neck. She’s threatening him that if you don’t listen to me, you know, I’m gonna kill myself that kind of thing. And then at the same time, she would come home with all this jewelry boxes and something and said, “if you just leave her, I’ll give you this,” you know? It’s like a desperation. And all this time, I wish they met me. If you meet somebody you start talking about things. So a lot of barriers can be just removed. It’s just that when you don’t know people, it’s very easy to hate.

Yochai Maital: And they wouldn’t meet you?

Ziporah Rothkopf: They wouldn’t. Listen, I know what they went through. How could they love goyim?

Yochai Maital: Emm hmm.

Ziporah Rothkopf: After what they went through? Not easy. And I can understand that. Really I do. I felt bad for them.

Yochai Maital (narration): But she wasn’t willing to give up on this relationship.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Through the divorce and everything. I don’t trust any more people, dog eat dog world. You take whatever you can, you know?

Yochai Maital (narration): Meeting Moshe had suddenly turned life sweet again.

Ziporah Rothkopf: It was like all feels right.

Yochai Maital (narration): To better understand his world, she began going to Torah and Judaism classes. For her, it was a revelation.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Once you started learning and practicing, you just feel the healing is on the way.

Yochai Maital (narration): In 1981, she converted and took the name Ziporah. Shortly thereafter, she and Moshe got married. Their wedding was a small affair attended by only a handful of people. Moshe’s family didn’t show up.

Ziporah Rothkopf: It was very close friends who knew really what’s going on with us. I cooked for my wedding because we didn’t have money. I made a first kosher Korean, so that was good.

Yochai Maital (narration): Moshe was a young doctor at the time, about to complete his residency in ophthalmology at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. As he was contemplating his next career move, he ran into a colleague who was on his way to interview for a position at a military hospital in Hawaii. Wanting to put some distance between himself and all the complications his new life choices had brought about, Moshe spontaneously asked his friend…

Ziporah Rothkopf: “Would you mind if I go too?” He said, “go ahead. There’s a two hundred fifty other people and there’s one job.” So… so Moshe ended up actually getting that job. It’s all Hashem. Really, it’s all Hashem.

Yochai Maital (narration): But alongside the good news of his acceptance, came some very bad news. Moshe’s father was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer.

Ziporah Rothkopf: They live like maybe two weeks, three weeks, maybe four weeks. Goes like that very fast, pancreas cancer. Moshe started feeling so bad to leaving his father and moving to Hawaii. Meantime, the Hawaii going crazy – “we need you right here now!”

Yochai Maital (narration): Not knowing what to do, Moshe and Ziporah decided to consult their rabbi – Shlomo Carlebach.

Ziporah Rothkopf: So we mentioned to Shlomo about what we are going through and he said, “you know this is big. This is too big for me. You need to go to a big, big rebbes, big rebbes to get a bracha. That’s what Shlomo said.

Yochai Maital (narration): He sent them to one of his rabbis – the Ribnitzer Rebbe.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Ribnitzer Rebbe was like a very unknown, mystical rebbe, old rebbe from Russia. And he lived in Monsey.

Yochai Maital (narration): The couple boarded a late night bus.

Ziporah Rothkopf: It was like midnight, because he only sees people midnight on.

Yochai Maital (narration): But when they got to the Rebbe’s office, he wasn’t there.

Ziporah Rothkopf: It just happened that night was the Ribnitzer Rebbe’s rebbe’s yahrzeit. So he’s not seeing anybody. And he’s just farbrengen with his chasidim.

Yochai Maital (narration): Moshe went into the synagogue, and started elbowing his way through a mob of dancing and singing chasidim, all the way towards the Ribnitzer Rebbe. But when he finally got close enough, he saw that the old Rebbe had…

Ziporah Rothkopf: Kchh… He just fell asleep. Meantime, me, I couldn’t go into the men place. So I’m like standing outside in th.. by the kitchen. I’m standing there. And it’s dark, and rainy. And somebody tapping my, you know, my shoulder? She said, “who are you?” So I say, “who are you?” She says, “I’m the rebbetzin.”

Yochai Maital (narration): The old Rebnizter Rebbe’s wife.

Ziporah Rothkopf: The rebbetzin was young! The rebbe was like ninety-years-old. And she’s like forty-fifty years old. She said, “what’s troubling you?” So I said, “you know, I just got married and my father-in-law… [goes to under].

Yochai Maital (narration): Ziporah told the Rebbe’s wife the whole saga. The reason for their late night visit.

Ziporah Rothkopf: “We just don’t know what to do, you know?” So she says, “call your husband.” And then we sit down. She basically says like this, “your parents are the survivors that worked so hard that their dream is you become a greatest ophthalmologist and if this Hawaii trip to going to Tripler’s Medical Center become ophthalmology, then you should carry their dream, rather staying here. You should go, you know? You should go and Hashem – in his ultimate mercy – before anybody passes, Hashem shows to a person the entire their life like a film. And all the questions you had – Why? Why? Why? – you know? All that stuff is gonna be all answered. And then they will see from the beginning to the end, and then one day they will see your value Ziporah. Don’t worry, Hashem will take care of them. Don’t worry, move on, move on. Because Hashem will make a peace with your father on the day of his leaving this world.”

Yochai Maital (narration): The rebbetzin then handed them a piece of paper, and asked them to write a little note together.

Ziporah Rothkopf: It’s called a kvitel like all the wish list, the what you need to be fixed, need to be answered. Need to be yoshua. “So you write it all that down and give it to me. Tomorrow morning, when Rebbe start davening, I’ll slip this into his tallis,” that’s what she said. “And then you should go with a peace.” As soon as we come home, it was already four o’clock, five o’clock in the morning, and we fell asleep and seven o’clock phone rings. And Moshe got up and then answered the phone it was his sister. His sister says, “Moshe, Moshe, you gotta run to the hospital right now! Daddy had a chemotherapy, and he’s hallucinating. And he is calling everybody ‘nazi.’ Moshe, you gotta run.”

Yochai Maital (narration): Moshe sprinted to the hospital, where he found his belligerent father being restrained in a straight jacket.

Ziporah Rothkopf: My husband says to father, “Daddy, what’s going on?” you know? He said, “why did you come here? You’re not my son. You got what you want, get away from me,” like that, but like very angry. So Moshe started to hugging him and touching him. And then saying to him, “maybe I’m not your son, but you’re my father, you’re my teacher, you know?” They started hugging and crying. And he spent sixteen hours that day, made a peace with his father.

Yochai Maital: Wow.

Ziporah Rothkopf: This is right after the bracha. She probably slipped in. Now I’m telling you, just overnight… overnight, all our problems kind of kind of solved.

Yochai Maital (narration): Moshe’s dad died several weeks later. They had, by then, already relocated to Hawaii, where they lived for the next year, and where Ziporah gave birth to their first child. In many ways, the rebbetzin’s blessings came true – these were very happy years for them. But all along Ziporah carried a certain sadness within her. Not for a second did she forget about her two children back in Korea, being raised by an ex-husband who wouldn’t let them even speak to her. And as time passed, the longing just grew.

Ziporah Rothkopf: It was time for me to really, you know…

Yochai Maital: Yeah.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Have my kids to know where I am? Who am I now?

Yochai Maital (narration): So following his wife’s request, Moshe asked to be transferred to Yongsan Garrison Military Hospital, near Seoul. They rented a big house near the base, and before they had even landed in Korea, Ziporah’s mother and three of her unmarried sisters had already moved in.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Moshe says, “why are they here? Wha…. wha are… What are they doing?” My mother is that kind of person. She thinks this is the right thing to do. I’m moving in. But it was a disguised blessing because I had built-in babysitters. I have three sisters, my mother, five women. One of my sisters flautist, her classic music is a ringing entire day in the house. And the Shabbos everything shut down. And then now we’re singing for Shabbos, you know, davenings and kiddush and everything.

Yochai Maital (narration): But one thing was missing from this picture of familial joy – Ziporah’s children.

Ziporah Rothkopf: There was a lot of lashon haras.

Yochai Maital (narration): Slander, bad mouthing, evil gossip.

Ziporah Rothkopf: A lot of lashon haras. And they were very scared to meet me because they were scared of the father because there was a lot of threats. You know?

Yochai Maital (narration): It took months, even years, but slowly, patiently, Ziporah forged a new connection with her kids. First with her daughter, and then, eventually with her son, as well.

Ziporah Rothkopf: It took long time for him to come around.

Yochai Maital (narration): By the time she left Korea, Ziporah and Moshe, who now had two kids of their own, would regularly host her whole Korean family – the kids from the previous marriage, her mother and all her sisters – for Shabbat meals.

Ziporah Rothkopf: When we were leaving my mother said, “I wish I had a Shabbos because… how wonderful. You don’t have to worry about money, the answering the phone… all that cut out and just focus in family together. The food is already ready and they have a guest and relaxed, is a different pace of Shabbos menucha, shalom and… and rest. So my mother told my husband, “I wish I had a Shabbos.”

Yochai Maital (narration): Ziporah probably would have stayed in Korea, enjoying the best of both worlds. But just as Moshe had followed her, she knew that it was now her turn to follow him. They returned to the States, to Lakewood, New Jersey, to be closer to Moshe’s aging mother. Despite the deathbed reconciliation between Moshe and her late husband, despite two new grandchildren, she had never truly come to terms with the marriage. With Ziporah.

Ziporah Rothkopf: My mother-in-law so stubborn. She comes to my Shabbos table, she wouldn’t touch my food for whole ten years.

Yochai Maital (narration): But here too patience paid off. Ziporah eventually found a path to her mother-in-law’s heart – through her cooking.

Ziporah Rothkopf: I made a special Shabbos fish. Whitefish with a spicy, and it’s a whole fish, and then I’m telling you, she loved it. We still talk about it, she has a like grave of bones… on plate. She loved it.

Yochai Maital (narration): Meanwhile, Moshe started a private practice. Ziporah ran the business.

Ziporah Rothkopf: He always said I’m working for my wife.

Yochai Maital (narration): And business was – baruch hashem – going well. Soon they were expanding.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Thirteen offices.

Yochai Maital (narration): All in all life shined on Ziporah. Three decades earlier she had left Seoul – in shame and tears – hoping to make something of her life. And she did. Ziporah was successful in love, in business, and was blessed with a warm and loving family. But still – after all these years – she felt a lingering sense of restlessness.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Whenever I go to Eretz Israel, I just felt so complete. So I told my husband, “we have to live in Eretz Israel, you know? We have to live in Eretz Israel. This is where we have to root here with our family.”

Yochai Maital (narration): So in 1996, Ziporah and Moshe once again picked up and moved. This time to Jerusalem’s Old City.

Ziporah Rothkopf: The Old City is a heart of hearts. You want to do anything, Old City. That’s where the world was created. Adam and Chava was created. That was where Avraham sacrificed Yitzhak. Everything came from there.

Yochai Maital (narration): Ziporah had “ridden” life from Korea to Vegas to Hawaii to Lakewood and finally to Jerusalem. And that journey changed her profoundly. I mean, today she is a devout charedi woman who wakes up at 4am to go daven at the Kotel. But in other ways – significant ways – she’s still Bung-Ja from Seoul. See, there has always been one thing she simply couldn’t leave behind – her food. And now that she was in the holy city, now that she arrived at her final destination, she had one last dream to fulfill.

Ziporah Rothkopf: I made my mind. From now on, I’m gonna work for my dream – make a kosher Korean food. Oh this was my dream for forty years. I’ve been cooking kosher Korean food all my life because I could never leave my food. I can leave my land. I can leave my family. I couldn’t leave my food. I always made my own kimchi, and my husband loves my food. He said one of the reasons he got married to me is because of my food [Yochai and Ziporah laugh].

Yochai Maital (narration): So Ziporah decided that Moshe shouldn’t be the only one who gets to enjoy her kosher Korean cuisine. She opened a restaurant in the Old City.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Seoul House!

Yochai Maital (narration): And a food company.

Ziporah Rothkopf: The food company is a KOKO – Kosher Korean. So now my stuff is in Amazon.

Yochai Maital (narration): KOKO ships glatt kosher Korean dishes – like fermented soy sauce, kimchi.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Kimchi.

Yochai Maital (narration): Gochujang.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Gochujang.

Yochai Maital (narration): Cochagaru.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Cochagaru.

Yochai Maital (narration): And doenjang.

Ziporah Rothkopf: Doenjang. Doenjang.

Yochai Maital (narration): All around the world.

Ziporah Rothkopf: My food is authentic, natural, healthy food. That’s what I’m interested in.

Yochai Maital (narration): When Ziporah talks about KOKO, her restaurant, the fermentation workshops she leads or the virtues of kimchi…

Ziporah Rothkopf: Really the ultimately what I want, is I want to grow the kimchi vegetables what I need, here in Israel.

Yochai Maital (narration): She has this glint in her eye. I can’t help thinking that for her it’s about much more than just the food. It stands for something bigger – it represents the merging of her two different identities and cultures. The one she was born into, and the one she chose. It’s her way of being both Bung-Ja – the phoenix – and Ziporah – the Hebrew bird.

For some people, such as Tali Aronsky, life is a meal: It starts off with exciting little tastes, it progresses to heavy dishes and main courses, and it’s ultimately resolved with the sweet flavor of wanting more. So how can chicken drumsticks, kubeh soup, hard boiled eggs, lamb biryani and lahme bi ajeen tell a story of love, loss, despair, hope and finally freedom? Zev Levi treats us to an unusual seven course “meal of life.”

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): And now, back to our episode. For some people, such as Tali Aronsky, life is a meal. It starts off with exciting little tastes, it progresses to heavy dishes and main courses, and it’s resolved, ultimately, with the sweet flavor of wanting more.

Tali Aronsky: Somehow through my taste buds, I became in touch with myself. I don’t even know… I’m a big foodie and I cook a lot. And there was something about the food that brought me back into the brotherhood of people. You know, into like, ‘humanness.’ Hi, I’m Tali Aronsky living in Jerusalem for these past six years, originally from Brooklyn, New York.

Zev Levi (narration): First course – the hors-d’oeuvres.

Tali Aronsky: I met Tal, the man that I would marry, at a friend’s wedding. So I remember it was a weekend wedding upstate New York in a beautiful place called Germantown, and they had rented out this area that was really beautiful and overlooking the river. There’s a kind of like, exhale, that you do when you get to these places that are green and overlooking the water. And it’s just like you’re in nature, and there are stars and there are fireflies at night. You really feel yourself being able to relax. It started with like a 5:30am boat ride. [Laughs] 5:30 in the morning – tired, groggy, not wearing makeup – wearing my glasses and my Crocs, you know, not my like, ‘let’s meet the menfolk attire.’ But it happens when it happens. It got really cold and we just started chatting, and then we got a blanket, you know, and then I remember the boat shifted, and I almost fell overboard and Tal saved me. It was like a very classic almost Titanic moment, I literally almost fell overboard. He grabbed my arm. And it was like that manly you know, ‘I will protect you from the currents,’ and I remember that was one of the things that like made a little, you know, a little switch in my head that said, ‘ah, there might be a future here.’ It was almost like a Tarzan who like came swinging through the vine and popped into my life. And there was a before and then there was an after. But yeah, that’s really in my memory how… how we got started.

Zev Levi (narration): Second course – the appetizer.

Tali Aronsky: We had a great wedding. We got married at the Israel Museum. Tal is an artist and I am a… a fan of the arts. You had a lot of Tal’s artists friends who are more secular, and then you had my more hippie dippie orthodox friends and it really was a mix of people at the Israel Museum and overlooking the Knesset. And that just was something very Jerusalem and very special about it. It was really good food. I remember they had, like, a Jackson Pollock dessert, you know, with kind of different glazes of things… like splattered paint. It was really a labor of love, our wedding, like I don’t know, just a lot of personality and personhood went into it. Umm… So something that I hadn’t been familiar with growing up as a good yeshiva, you know, bachurette in Flatbush, but I remember Tal thought that like one thing that you had to have at your wedding along with arak and different things was like a little (not even so little)… A glass bowl full of joints so that people could just, you know, partake of the ktoret incense libation. So there was also that – a little bit of something for everyone [laughs]. Towards the end of the wedding, I was, you know, going around to different groups of people and thanking them for coming. And I remember smelling the pot and I just was happy that people were enjoying theirselves and just seeing people smoking up and kicking back and relaxing, like, you know it’s a good sign when Tel Avivi people stay in Jerusalem longer than they have to. You know that’s a good sign.

Zev Levi (narration): Third course – the drumsticks.

Tali Aronsky: I remember the chicken drumsticks that told me that I was married. You don’t realize until after your wedding how famished you are. We got married Friday morning, and I remember they packed for us some food and we came home and it was already almost erev shabbos. And I remember when we came home and we were so hungry. I remember us standing barefoot in our kitchen – just two famished people opening up tupperware, and whatever was next, that’s what we were eating. And in one hand we were holding drumsticks, and then we’re also eating baklava, beef carpaccio, salmon wellington… And we were, like, laughing and talking together in the kitchen as the siren was going off in Jerusalem and shabbos was coming in.

Zev Levi (narration): Fourth course – the soup.

Tali Aronsky: I remember the kubeh soup that was a turning point in our marriage. We got married June 6th, and about a month-and-a-half later, we were hosting a bunch of my friends who were in town for the summer, and we’re hosting them for Friday night. We lived in Bak’a on like a first floor in this beautiful apartment and I had a really really nice big backyard and we had a long table. I mean it felt like some scene out of like a Tuscan movie where you know you have your friends and you’re eating under the archways and everything is so beautiful and you had the smell of jasmine in the air. I remember being in the middle of the meal, we had all these friends over and it was so great. And I had my hair covering and all that. And then in the middle of the kubeh soup, like I remember realizing that Tal wasn’t looking at me anymore. Between Tal and I, this big rift was growing. And it all happened that night. I remember suddenly, like, almost like my stomach dropping. Like suddenly I felt it, like ‘wait, wait, wait, what happened? What happened? Why is he ignoring me now?’ It almost felt like a trap door in a play. Like you know, when you have those trap doors in a stage floor and people suddenly can like disappear? That’s what it felt like. That particular soup, I remember, Tal made it. It was beet soup, and it’s this gorgeous, rich, red, pink, fuchsia color. It’s really a beautiful soup. I just always remember that it was such a haval, that it was such a shame that we had spent so much time preparing a dish for guests, and then the meal gets ruined. I mean, I did put on a brave face, so it didn’t get ruined for other guests. But like half of my head is like entertaining our guests and happy that they’re there. And the other half is like ransacking my brain. And like almost like spooling the tape back to think, ‘what did I say? And did I say something off to Tal?’ Like I remember, like I couldn’t… ‘Like where… where was the dog buried? Like, where was the thing that had happened?’ I remember thinking, this isn’t healthy. But look, we’re still living together and sharing a bedroom. And he’s not talking to me. And if he wasn’t talking to me, he wasn’t talking to me. You know, it started off with like two days, I was thinking like, ‘did I have an affair in the middle of the night and not realize?’ And then it kind of like progressed through one Shabbat, where we’re both in the house and he’s not talking to me. It almost was like my existence became smaller and smaller and smaller. And I can’t describe it, your whole life is consumed by them being upset with you and you don’t understand why and then you take it so much to heart. And you’re so… you’re so kind of like thrown off kilter, that it just sucks all the life force out of you. And it’s hard to make clear decisions when that’s going on. It had gone on for so long, I remember at a certain point not being able to be in the house with Tal any longer. And he didn’t talk to me literally for two weeks. I mean how did he suddenly start talking to me? I don’t know. There was never any apology so I never had a warning sign that it was coming. He would just suddenly start talking. And I remember, that’s when he shared with me that it was the kubeh soup. He had set the table with like disposable napkins and paper plates. And because we were having hot soup, I switched out the plastic spoons and I replaced them with metal spoons. He felt that I had “canceled him.” I remember that’s how he phrased it. And I had overridden his decision and switched out the plastic for the metal spoons. And there was something very emasculating to him or something I don’t even know. It was so – in my mind – trivial that even if I would try to be like the ‘better wifey’ I couldn’t even predict that. Like, clearly I wouldn’t switch out the spoons again. But like, you know, those aren’t the kind of things that you could like plan for. You know, a newlywed couple to not speak – to not speak – for two weeks. It just felt like senseless torture. It’s embarrassing to share, you know, these… like on the one hand, of course, clearly you’d get sympathy, but it’s embarrassing to share what’s been going on because you feel somewhat complicit. And yeah, I remember there was something about that experience that it was like, I remember knowing that it could never… it could never happen again.

Zev Levi (narration): Fifth course – the egg.

Tali Aronsky: I remember the boiled egg that told me I was really alone. When I left Tal, I left with the clothing on my back. Like borrowed underwear, I borrowed pajamas, borrowed Shabbos clothing. My body was so in ‘fight or flight’ mode. And a friend of mine offered to stay in her apartment. I remember her saying to me, “I want to nourish you. I want to nourish you.” But I think that was just how she saw herself, but not actually the person that she was. And she didn’t actually nourish me. And didn’t give me any food. And it sounds so stupid but the amount of energy to like just feed myself was so great. To be like, ‘Tali, you know, it’s already 4pm and you haven’t eaten anything and you need to eat.’ I had just enough energy to like boil an egg. You know, there’s something very Eicha-ey about it. There’s something very mournful like, it’s like the most basic food. It’s round. You just eat it, you know? I was going to be eating a boiled egg, and I put it right before I took a shower. And I remember when I came out, I saw my friend – the same one who said she wanted to nourish me – I saw her like eating the egg and like the shells were on the counter. And I remember just thinking… I…. I hadn’t really… I had barely even been eating, I wasn’t really eating and I wasn’t really sleeping, and she was eating my egg. It’s as if she had taken it out of my mouth. I can’t describe it. Um, yeah, so I didn’t stay there too long. And I started moving from place to place, staying in different places for two weeks at a time.

Zev Levi (narration): Sixth course – the lamb biryani.

Tali Aronsky: I remember the lamb biryani that made me feel human again. I went to meet a friend on Emek Refaim Street in Jerusalem. And there’s a really good wine shop there. While I was there, I met this Indian guy named Erwin Prabhu. And he could just sense that there was something wrong that something tumultuous had happened in my life. And I remember him saying then and there, “I want to cook for you.” And I was like “what?” And he was like, “yes, let me cook for you.” At the beginning, I was like, ‘och, he’s a guy. And does want sex? Does he want some kind of quid pro quo? And what, you know, who… who is this character?’ But I was in such a desperate state, that – like – I was almost like a machine like I didn’t even have enough energy to fully explore it. Meaning I was moving like a zillion miles a minute, trying to like… New job, and I need a place to live, and I need to get a gett, and there was like so much craziness going on, that when he first made the offer, “OK, maybe.” You know, when he says “I’ll see you here tomorrow in the shop” – I think it was like a Tuesday – “I’ll see you here Wednesday at 8pm.” I’m like, “ich veiss, fine.” You know, I don’t know. I remember actually showing up. But not knowing if he would show up. And there he was. And I remember being very moved by not only did he have all this food for me, but he left right after. He didn’t linger. It wasn’t, “now I’ll walk you home,” or “because I gave you food. I can now ask you personal questions.” There was no weirdness. He gave me the food, said goodnight, said “I’ll see you in two days,” and left. And I remember coming home, the apartment was very sparsely furnished. No one had lived there in a while, so there were broken panes of glass and I’m like, in this apartment shivering and the food was so good. Different spices than I’m used to. It’s curry leaves. It was just so yummy. So biryani is like rice and vegetables and lamb. And then there was also like a pickled sour-sweet mango thing and then there would be the tamarind winter soup. Like the soup that his grandmother made in the winter. There was something about it that almost like… almost thawed me back into like humanity. Like my senses weren’t just fear, panic, safety, survival. I suddenly had mango and tart and spicy and new. Like somehow through my taste buds, I became in touch with myself again. And that became our ritual. I would see him every two days and I would return the empty containers and he would give me new ones. This food drops like from the stork into my apartment. It really felt like mana. Like it really just felt so heaven-sent that it didn’t feel weird to take it. And no matter how crazy my days were, my clothing is still in garbage bags. I’m moving from house to house, but in the evening I always knew that one meal a day I would have a home-cooked meal and it was so nourishing.

Zev Levi (narration): Seventh and final course – the lahme bi ajeen.

Tali Aronsky: I remember the lahma bajin that told me that I was home, and I was safe and not going anywhere. So the parsha wherein I left Tal was Parshat VaYetze, you know ‘And He Left.’ And from the first anniversary on, every year I hold a seudat hodaya. I have like a meal of thanksgiving. So I always save up like good recipes and it really is a feast. And this past year, I found a recipe for lahma bajin. Lahma bajin is a meat with bread, that’s what it literally means. It’s almost like a meat pie. It’s almost like a pizza, only instead of like dairy pizza, you have meat. But it’s a meat flavored with pomegranate molasses and tamarind and onion that’s chopped really finely, and then – you know – with… you’ll have parsley in there and it’s like a sweet tart meat ragu almost. And then you top it with pine nuts and I made my own bread. And then I served it with tehina with sumac. Sumac is like a red berry. It reminded me of Pesach where you say like, you know, “ha lachma aniya – this is the bread of my affliction.” I remember thinking like it’s not just the bread and my affliction. Like when I left it really was like an exodus and it was be’hipazon and I left really quic…. I didn’t even have a contact lens case. And this time I am holding up bread, but it’s like high-end bread. It’s spelt that I had time to make. And I’d been cooking for two days getting this whole… all the different dishes ready. And that really shows that like ‘right, I wasn’t still running away.’ Nothing says being settled, like having two days to cook for a feast. There’s something about sitting together at a meal that’s the direct opposite of running out of a house. And there was something about the food that brought me back into the brotherhood of people. You know, into like ‘humanness.’

Yochai Maital and Zev Levi scored and sound-designed the episode with original music and music from Blue Dot Sessions. Sela Waisblum created the mix. Thanks to Niva Ashkenazi, Oren Harman, Dalia Weil, Erwin Prabhu, Wayne Hoffman, Esther Werdiger, Sheila Lambert, Erica Frederick, Jeff Feig and Joy Levitt.

The end song, ABCD, is sung by Shaizee, Abie and Sol Harman.