Sa’adia Kobashi was born in the small village of Khubesh, Yemen, in 1902. During Passover of 1909 his father Yihye, who was the village leader, hosted a meeting to discuss the idea of moving to the Land of Israel. Though the inhabitants of the village (most of whom were silver- and copper-smiths) lived in peace with their Muslim neighbors and were financially comfortable, they were determined to fulfill their dream, and decided to begin the journey to Zion the day after Shavuot.

And indeed, seven weeks after that meeting, they set out and – led by a Muslim guide – made their way to the coast of the Red Sea by foot, donkey and camel. In Midi, they boarded a sailboat, at Metzawa they changed to a steamboat to Port Said, and finally arrived in Jaffa in mid-summer.

Once in the Land of Israel, the group walked to Jerusalem, and seven-year-old Sa’adia began attending religious schools. He ultimately became a teacher, a principal, one of the leaders of the Yemenite community in Israel and its representative on Moetzet HaAm, the Provisional State Council.

Stuck in besieged Jerusalem, Kobashi was unable to attend the Declaration ceremony itself, and added his signature to the scroll during the first ceasefire, a month later.

He and his wife Malka had three children, and his son Avinoam, who is himself ninety-one, recalls that his father wore a jacket, tie, and hat every single day of his life.

Sa’adia Kobashi was a modest man, who preferred education to politics, and religion to public affairs. He died in relative obscurity in 1990, at the age of 87.

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: there were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

Today we’ll meet Sa’adia Kobashi, and his son, Avinoam Kobashi. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Act TranscriptAvinoam Kobashi: As I got older, I started driving on Shabbat, and I remember that this one time I came over to my father’s house on Motzei Shabbat, on Saturday night. I made sure, of course, to arrive after Shabbat was already over, but apparently I came too early, almost immediately after the end of Shabbat, so he said to me, “Avinoam, I’m really happy you came to visit me. I really am. But if you had come just a little bit later, I would have been even happier.” That’s the man he was.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Avinoam Kobashi, the son of Sa’adia Kobashi, a rabbi, a licensed poultry slaughterer, an educator and the lone representative – among the signatories of the Declaration of Independence – of Yemenite Jewry.

[Signed, Sealed, Delivered? introduction]

Today we’ll meet Sa’adia Kobashi, and his son, Avinoam Kobashi. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series. Here’s our producer Yael Ben Horin with Avinoam Kobashi, Sa’adia Kobashi’s son.

Yael Ben Horin (narration): During Passover of 1909, the heads of the families of the small community of Khubesh, Yemen – most of whom were silver- and coppersmiths – met up in the home of their village leader – Yihye Kobashi, Sa’adia’s father – to discuss the idea of moving to the Land of Israel. Though they lived in peace with their Muslim neighbors and were financially comfortable, they were determined to fulfill their dream, and decided to begin the journey to Zion the day after Shavuot.

And indeed, seven weeks after that meeting, they set out and – led by a Muslim guide – made their way to the coast of the Red Sea by foot, donkey and camel. In Midi, they boarded a sailboat, at Metzawa they changed to a steamboat to Port Said, and finally arrived in Jaffa in mid-summer. In a memoir that he wrote for the occasion of his eightieth birthday, Kobashi recalled a terrible storm they had encountered en route. “Most of the people on the ship were sick,” he wrote, “and one of them, my sister Badra’s firstborn son, may his memory be a blessing, died, and was cast into the sea.”

Once in the Land of Israel, the group walked to Jerusalem, and seven-year-old Sa’adia began attending religious schools. He ultimately became a teacher, a principal, one of the leaders of the Yemenite community in Israel and its representative to Moetzet HaAm, the Provisional State Council.

Stuck in besieged Jerusalem, Kobashi was unable to attend the Declaration ceremony itself, and added his signature to the scroll during the first ceasefire, a month later.

He and his wife Malka had three children, and his son Avinoam, who is himself ninety-one, recalls that his father wore a jacket, tie, and hat every single day of his life.

Sa’adia Kobashi was a modest man, who preferred education to politics, and religion to public affairs. He died in relative obscurity in 1990, at the age of 87.

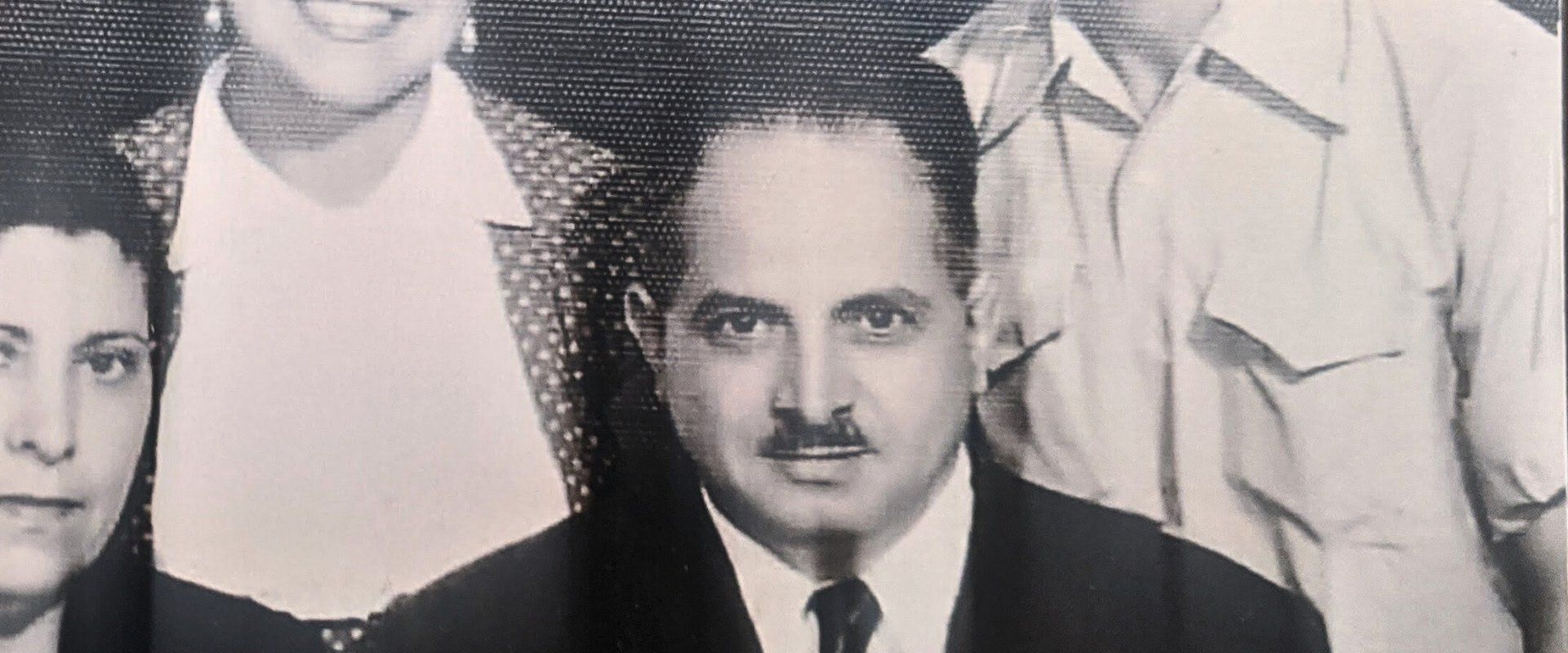

Here he is, in a 1961 interview for the State Archives, sharing a message for future generations:

Sa’adia Kobashi: I shall say my part. It is written, “and Joshua defeated Amalek and his people with the edge of the sword.” According to this verse, the State stands primarily on its material might, on its military force. But on the other hand, in the previous verse it is written, “and so it was that when Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed; and when he let down his hand, Amalek prevailed.” In other words, according to this, the main force upon which the country rests is spiritual. And so we learn that the material might is the main thing and the spiritual strength is the main thing. The one cannot exist without the other. And above those two forces is the belief in God and the Torah of Israel and the Land of Israel.”

Avinoam Kobashi: I’m Avinoam, the son of Sa’adia Kobashi. He was born in Yemen in 1902, in a village called Khubesh, and that’s where the name ‘Khubashi’ comes from. I mean our original name is Levi, he was Sa’adia Levi. But everyone’s a Levi, so which Levi? Sa’adia Levi Khubashi from Khubesh. Later on when he went to school here in Eretz Yisrael, they didn’t know how to say Khubeshi, so instead of ‘khaf’ they said ‘kaf’ and it became ‘Kovashi.’ That’s how our name was born. In any event, they lived there and in 1909 they made aliyah to the Land of Israel. He was seven years old. Coming here was their utmost desire, their greatest wish. So when they arrived they all dropped to the ground and kissed the earth, literally kissed the earth, and then they continued on to Jerusalem by foot. Whoever had enough money, rented a donkey and put their baggage on the donkey’s back, and then everyone just walked beside the donkey. You know, it’s funny, once – many years later – my car was in the shop so I picked up my father in my wife’s car, which was much smaller than mine. And I asked him, “dad, are you comfortable in this car?” So he looked at me and said, “yes, of course I am. It’s way more comfortable than the donkey I didn’t have when I came from Yemen.” Here in Eretz Yisrael he lived in great poverty. They had a difficult life, very difficult. And poverty then? It meant you were hungry. Not like today where poverty is some sort of statistical definition – you know, the poverty line and everything. Today there’s a line! But back then, poor meant hungry. Simple. He told me he used to go to the market to carry baskets for older people so that they would take pity on him and give him a slice of bread or a piece of fruit or something like that. But my father never spoke about ethnic discrimination. He just didn’t feel it. On the contrary, he was very grateful and felt that he received many opportunities. In 1925 he graduated from the teachers seminary in Jerusalem. Three years later, in 1928, he got married and was sent as a Hebrew teacher to the children of the Jews of Aleppo, you know, Syrians, who had immigrated to America. I was born in the United States on January 1st, 1932. We came back to pre-State Israel when I was three, and we’ve been here ever since. By the time we returned, my father was considered to be a learned man and he loved the Torah and studied the Torah. And since the Yemenites were all deeply religious people, they chose him to be head of the Yemenite community. On November 29th, 1947, the UN announced the Partition Plan, and many Arabs were outraged and began rioting. So what did my father do? He went out to help build the fortifications. In 1948 we didn’t have a radio. There were only a few families in the neighborhood who had radios, so we went over to the neighbors to hear the Declaration of the State. Now we lived in Jerusalem at the time, and Jerusalem was under siege. So even though my father was invited to the Declaration, he couldn’t make it to Tel Aviv. There was just no way, nothing to be done. So a few days or weeks later, I don’t know, I can’t remember, they sent him a Piper, an airplane, to take him to Tel Aviv to sign the Declaration of Independence. And he went and then immediately returned to Jerusalem by plane. He said, “I signed with trembling hands and with gratitude to the Creator of the World who gave me the privilege.” He wasn’t a funny guy, my father. He was a very quiet and serious man, who was completely and utterly devoted to his role as an educator. See, shortly after the State was founded, our family moved to Tel Aviv, and since he was already an experienced teacher he got a position with the Ministry of Education as a supervisor in the religious Zionist school system. And then, once the large-scale aliyah from Yemen – Operation Magic Carpet – began, he left this relatively senior position as a supervisor in the Ministry, and went to set up a school and teach in Rosh Ha’ayin, which was a ma’abara, a temporary transit camp the government had set up for new immigrants from Yemen. It was all out of love, really, because career-wise it made no sense. I mean he made much less money as a principal than he had as a supervisor, and what’s more, he had to take three buses to get to work every morning. You know, it wasn’t like today where you just get into your car and you’re there in ten minutes. He said it would take him two hours to get to the school. And Rosh Ha’Ayin itself? I mean, at the time it was mainly mud and dust and everyone lived in tents. But every day there he was. Every single day. He would always be the first to arrive at the school. That’s the kind of man he was. And folks in Rosh Ha’Ayin remembered that, and many years later even named a street after him there. At home, our entire family would gather every Friday night for a Shabbat meal, and my father would make kiddush in the Yemenite style, and everything was traditional, just like it had been in Yemen. And that was also the education he gave us. Look, even today I can still chant the Torah with all the traditional Yemenite melodies without any preparation or anything. [Chants]. I remember that one time, I told him about a friend of mine who wasn’t religious. And he said, “what do you mean, he’s not religious? If he lives in the State of Israel, he’s not only religious, but pious. Because according to the Talmud, the act of living in the Land of Israel outweighs all the other mitzvot, or commandments, of the Torah. And why is that? Because those who live in the Land of Israel build it, defend it, fight for it, and sometimes even sacrifice their lives for it. And that’s kiddush hashem, the sanctification of God’s name. And all the donors in America, who give millions to Israel? They’re paying damim, which means money. And those who live here in the Land of Israel, pay with dam, blood. So I ask you, who is more religious?”

At the same time, and despite his religiosity and approach to the land, my father was a moderate man. For example, he was in favor of dividing the Land of Israel. He used to say that it was pikuah nefesh, a matter of saving lives. That if there will be peace with our neighbors fewer people will be killed. Some might disagree of course, but he thought that the Land of Israel was holy, but that human life was holier. So he used to say that if it was up to him, he wouldn’t object even to dividing Jerusalem. You can’t always just say, ‘well, G-d gave us the Land, G-d gave us the Land.’ Yes, that’s true, but the reality on the ground is different. He taught us to hope that Israel would be a religious state, a traditional state. That yes. But instead, today, there’s extremism. And that makes me sad, and would have made him sad. Because the religious extremism today, and I’m saying this gently, has made Judaism an unbearable religion. In the Declaration, Ben-Gurion promised freedom of religion and conscience for all. But we don’t have that today. We live in a society of religious coercion. Take the Western Wall, the Kotel, for example. We thought that the Declaration talked about no discrimination based on sex. But at the Kotel women can’t pray in whatever way they want, and there are sections where they can’t even go. What is this?! Is that what we call freedom of religion?! Equality between the sexes? As far as I’m concerned, the Kotel shouldn’t even have a rabbi. It itself is a holy place, so it doesn’t need a rabbi. And everyone, men and women, should be able to do whatever they want – pray, read the Torah, whatever. Why not? And it’s not just the matter of religion and equality of men and women. I think we’ve lost our way as a welfare state too. Our governments – both this one and previous ones – don’t pay enough attention to poverty. All the politicians keep on making statements about how they’re fighting poverty and closing socio-economic gaps. But the reality is that more and more people live in poverty and the welfare institutions mainly serve the welfare of all kinds of machers who get paid for doing nothing. That makes me very sad. But at the same time, if my father was around today, he would be very proud of Israel’s military might, and he would say that if we would have had this kind of an army during World War II, there wouldn’t have been a Holocaust. Every year on Yom Ha’Atzmaut, Independence Day, I’m moved and excited as if it was the day the State was declared. That’s how I feel. And I conjure up the image of my dad in my mind’s eye, and I say to myself that I am privileged, lucky, to be the son of Sa’adia Kobashi, signatory of the Declaration of Independence.

For a fascinating memoir Kobashi wrote on the occasion of his eightieth birthday, see Yalkut HaLevi (Hebrew).

In 1961 Eliezer Whartman of the Israel State Archives conducted a series of interviews with 31 of the 37 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. For the full interview with Saadia Kobashi, see here.

Zev Golan’s 1988 audio interview with Saadia Kobashi is available here.

For a recent interview with Batya Herman, Sa’adia’s daughter, see this short video.

For Kobashi’s obituary, see this January 1990 Ma’ariv article.

In 1901, Hermann Burchardt, a German-Jewish photographer, spent a year living with the Jewish community of Sana’a, Yemen. Some of his magnificent photographs can be seen here. A far more extensive archive of photographs, taken by Shlomo Yefet, a Yemenite-Israeli Jew who went back to Yemen to assist with Operation Magic Carpet (also known as Operation On Wings of Eagles), which brought some 50,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel in 1949-1950, is available here.

For a Hebrew site devoted to the social and cultural legacy of the Jews of Yemen, including many links to traditional Yemenite music, see this website.

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubbers are Leon Feldman and Yoav Yefet.

The end song is HaMori (lyrics and music – Shlomo Machdon), performed by Daklon (Joseph Levy).

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.