Since the start of the military operation in Gaza, countless reports by journalists embedded with the IDF troops have appeared in the Israeli media. But there was one eight-and-a-half minute-long TV broadcast that aired on Kan – the Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation – that stood out. In it, Riyad Ali, a 61-year-old Druze journalist from the town of Maghar in the Galilee, accompanied soldiers from the Golani Brigade who were operating in the Zeitun neighborhood of Gaza City. He spoke to a bunch of them, including one shy officer, Yussef, who just so happened to also be Druze. It was a pretty standard interview, but at some point something unusual happened: Unsatisfied, perhaps, with the officer’s guarded answers, Riyad took the mic and launched into an on-air monologue. He spoke from the depths of his heart about the discrimination the Druze population faces and reminded viewers that the Declaration of Independence promised all Israeli citizens equal rights, irrespective of race, religion or sex. Despite the Druzes’ loyalty, he went on, and despite the fact that six Druze soldiers have been killed since the start of the war, they still feel like second class citizens. That clip went viral. Riyad’s courage to speak up surprised and touched many Israelis, who are – these days – accustomed to a more patriotic tone on the news. But when he chose, in what seemed like a spur of the moment decision, to go public with his more complex views, Riyad wasn’t only speaking as a member of the Druze minority. He was also speaking as a man who, nineteen years ago, was himself kidnapped by Hamas in Gaza.

A journalist covers the IDF in Gaza, and is reminded of his time as a Hamas hostage.

Act TranscriptRiyad Ali: It was 19 years ago and I still remember those words that I start to repeat to myself: I am a kidnapped person.

Adina Karpuj: And yet 19 years later you decided to go back there.

Riyad Ali: Oh, yeah…three weeks ago.

(Recording from the broadcast)

Riyad Ali: I went there as an Israeli journalist. The seconds before I went with the soldiers to Gaza I felt the pain in my stomach. And I asked myself: What the hell you are doing to yourself? Why do you need to go back to Gaza?

Mishy Harman (narration): Hey listeners, it’s me, Mishy. So as you know, during these incredibly difficult days, we’re trying to bring you voices we’re hearing among and around us. These aren’t stories, they’re just quick conversations, or postcards really, that try to capture slivers of life right now.

Since the start of the military operation in Gaza, there have been hundreds, maybe thousands of reports by journalists embedded with the IDF troops. But one eight-and-a-half minute long TV broadcast that aired on the Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation stood out from the rest.

(Recording from the broadcast)

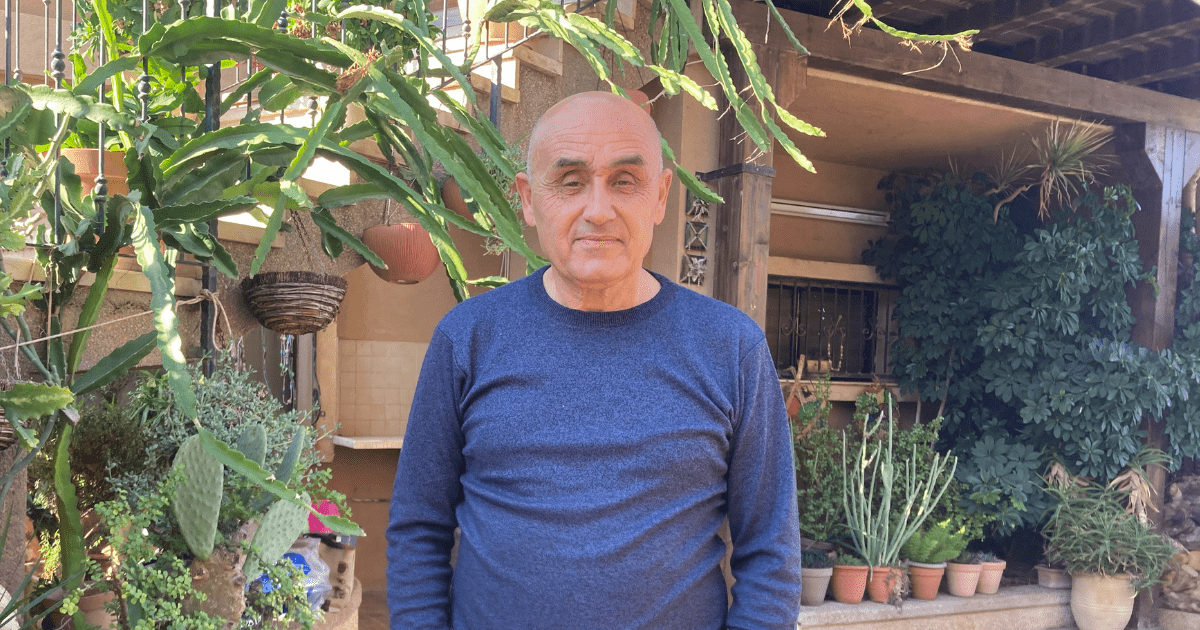

In it, Riyad Ali, a 61-year-old Israeli, Druze journalist from the town of Maghar in the Galilee accompanied some Golani Brigade soldiers operating in the Zeitun neighbourhood of Gaza City.

(Recording from the broadcast)

He spoke to a bunch of them including one shy officer, Yusef, who just so happened to also be a Druze.

(Exchange with Yusef during the broadcast)

It was a pretty standard interview:

“How are you doing?” “Great”

“What do you think about what’s going on?” “This should have happened a long time ago. We have to erase – mass erase Hamas.”

But at some point something kind of amazing happened. Unsatisfied perhaps with the officer’s somewhat guarded answers, Riyad the journalist, took the mic and launched into an on air monologue.

(Recording from the broadcast)

He spoke from the depths of his heart about the discrimination the Druze population faces. He said that the Declaration of Independence promised all Israeli citizens equal rights, irrespective of race, religion or sex, but that despite the Druze’s loyalty; despite the fact that they serve in the army; despite the fact that six Druze soldiers have been killed since the start of the war, they’re still second class citizens.

That clip went viral. Riyad’s courage to speak up surprised and touched many Israelis who are, these days, accustomed to hearing a much more patriotic tone on the news. But when he decided on the spur of the moment to go public with his more complex views, Riyad wasn’t only speaking as a member of the Druze minority. He was also speaking as a man who 19 years ago was himself kidnapped by Hamas in Gaza. Our producers, Adina Karpuj and Mitch Ginsburg went to talk to him.

Riyad Ali: My name is Riyad Ali. I’m a journalist. I work in the Israeli TV channel 11. I’m a Druze from the Druze community in Israel. We are a small community in Israel, about 120,000 people, about 1.5% of the Israeli population.

And here I am. I start to work as journalist in 1995, just two weeks before Rabin was assassinated. Two hours after they announced that Rabin was killed, I was here in my house sitting, following the news. And I noticed that I’m crying. And the question was why I am crying about a prime minister who I was critical about him. I didn’t hate him, but I was seriously critical about. And the answer was: it seems that inside me there is an Israeli who’d like to come out of the closest. The day after, I wrote my first column —about my grief of losing my prime minister.

I started to work in CNN in 2002 as a producer…field producer. And my advantage was my connection with the Palestinian people. I had a lot of good connections with the Palestinian Authority, with Hamas, with other parties there.

And going to Gaza was the normal things that we did those days. That was the Second Intifada—and we went there once a month at least.

And that day, 27th of September 2004, we went to our office there in the ninth floor. We finished our day work, and we went down to take a taxi to go to the hotel. Two to three minutes after we start to drive, the taxi stopped suddenly and someone approached the driver and asked: “Who is Riyad Ali?” And without thinking I said: “I’m Riyad Ali, it’s me.”

And few seconds after, the door next to me was opened, and two armed people with the cover on their heads, they pushed me out of the car. They accused me of being an officer in the Israeli secret services. They took me directly to a car who actually blocked us, and they pushed me inside the car in between the front seat and the backseat. They took my phone, my cigarettes, and they start to drive very fast.

You know, the first moments I tried to say something that it’s wrong. “I’m a journalist,” I shouted. And they respond in a strong fist in between my shoulders. They pushed me down. And I still remember the smell of the carpet in the car: ugly smell— till now, 19 years after, I still remember that smell.

And suddenly, the door of the car was opened, and they took me to an apartment. And once we are inside the apartment, they placed me on the chair on the middle of room. There was a black sack on my head. They tied my hands to the back of the chair; they also tied my legs.

For almost 36 hours I stayed there in the same position. And it was around the clock interrogation. Suddenly they freed my hands and for a few seconds I felt comfortable, you know, the fact that I’m a little bit more free.

And what happened next was that one of my kidnappers suddenly brush the pistol, the gun in my hands. And he asked me to use it.

And I said: “I don’t know how to use it.”

“It’s impossible, you are an Israeli secret services officer. You know how to use it.”

“No, I don’t know.”

And he start to push it forward, and I start to fight with him pushing it backward. And suddenly he took the gun from my hands and there was a silence around me.

And just try to imagine that the sack is still in my head. I can’t see anything. And I know there is a gun somewhere.

I start to try to place where the gun is, you know, and without the ability to see, I try to use my nose to smell, my ears to hear where’s the gun is placed around me. And I remember myself calculating the time in between the shooting and the pain. Would it pain when they shoot? Would it hurt? How long it could take from the shooting to my death?

I don’t know, it was seconds, minutes, you know. But suddenly, a burst of laughter. A loud laughter. I started to cry. People who are armed from head to leg are using their strength around me and I can’t do anything. But you know, the interrogation was the easy part. I forgive them that they hit me; that they humiliated me; that they threatened me.

But there’s one thing I will never, ever forgive them about doing that with me.

One of my kidnappers, he start to quote from the Quran. And he start to ask me actually to convert my religion to Islam. I’m hungry; I’m thirsty; I’m tired. It was hot inside the room.

And somehow I said to myself, one of two things are going to happen right now: or they already decided to kill me. And if they decided to kill me I would like to die as a Druze.

The other option that they are already decide to release me. And if they are going to release me I would like to come back to my family as a Druze.

I said to the guy who sat next to me:

“Sir, can I ask you a favor?”

He said, “Yes, of course.”

I said: “If you want to kill me, would you allow me to die as a Druze?”

I don’t know what happened to him. I didn’t see him. But he just left me. And half an hour after, they came and they told me that I’m going to be released.

Still, you know, the moment they tried to convert me to Islam is the moment that I would never allow myself to forget or to forgive. Because being a Druze is being me. They tried to take from inside me the thing that actually identify me.

You know, when I saw what happened in Israel in October 7th, it was actually the same thing. They didn’t come to Israel to release Palestine. They came to destroy the Israeli spirit, the Jewish soul. they came to destroy the Israeli existence.

That’s why I feel very sad in those days. Because there is a connection between the way they tried to convert me to Islam, and the way they behave in October 7th in Israel.

I saw the military, you know, movie.

Adina Karpuj: The 47 minutes of atrocities.

Riyad Ali: I saw that movie and one of the pictures I saw is a girl, about 14 years old, killed without her underwear. The act, it wasn’t there, but it was a girl. I have a daughter. And just to think that they did such a thing with… she’s still a flower, untouched flower… oh my God.

Adina Karpuj: We’re speaking almost two months into the war. There’s still many, many Israeli hostages in Gaza. Is there any word of advice…if you could channel something to them. Is there anything?

Riyad Ali: Just to believe that one day they will be released. You know, hope can help us continue breathe. Many people who are waiting for them here. And they should do whatever they can just to come back alive and let their belovers hold them.

Adina Karpuj: So Riyad, you just returned for the first time since your kidnapping. It’s been 19 years. What did you see?

(Recording from the broadcast)

Riyad Ali: It was the Israeli puzzle around. Israeli soldiers who came from Russia; Israeli soldiers who came from Ethiopia; Israeli soldiers who came from Morocco; and Druze soldier. I sat next to him, asked him about, you know, the war and the patriotic…he feels that he’s doing what needs to be done. And I asked him about being a Druze.

(Recording from the broadcast)

If there is anger about Israel, how Israel behave to the Druze. And he said: “No, I don’t want to talk about politics here.” And I respected his request. And I continued to my cameraman…I start to speak to the camera. And I told the Israeli people that here, in the field in Gaza, he’s a first class citizen, but that in his village: his family, his brothers, sisters, his wife…they are second class citizen. And that this is the moment in which Israel should rethink and promise this soldier once he comes back, whether alive or dead, he is coming back as a first class citizen.

(Recording from the broadcast)

You know, because we are not Jew, there is a difficulty of living inside Israel in a Jewish state. We are loyal to the Israeli state because we do believe that we both are sort of minorities in the Middle East.

The Druze community share the same memories, like the Jewish people. We were persecuted by the Sunni majority in the Middle East for many years. But despite what we do to the country, despite the fact that we are part of the country, despite that, our youth, right now, are fighting side by side with the other Israeli soldier in Gaza to protect this country.

The Israeli state always rejected us. They didn’t behave with us as equal citizens.

You can just look around in our villages and you can see the difference between Druze village and Jewish town. It’s a huge gap. Everything around you says discrimination: infrastructure, education, health system— everything around us in the Israeli Druze community is different from the Israeli Jewish communities. But my God, we are part of this…this place.

The end song is Nus Nus (“Half-Half”) by Noam Tsuriely.