Many of you have probably heard, or read about, Rachel Goldberg and Jon Polin, the parents of 23-year-old Hersh Goldberg-Polin, who was kidnapped from the Nova Party. In many ways they’ve emerged as the face of the hostage families – they’ve met with Biden and the Pope, they were on the cover of Time Magazine, Rachel has spoken at the UN and at the ‘March for Israel’ Rally in Washington D.C. And in all those places, as well as in countless other interviews, speeches and meetings, they’ve told the heartbreaking tale of the two text messages Hersh sent on the morning of October 7th, one saying “I love you” and the other “I’m sorry.” He wrote those messages from within a shelter, where he was hiding with 28 other partygoers. Eighteen of them were killed, and Hersh – whose left arm was blown off – was badly wounded. Shortly thereafter, Hersh and three others from the shelter were loaded onto Hamas pickup trucks and taken into Gaza. It has now been 55 days.

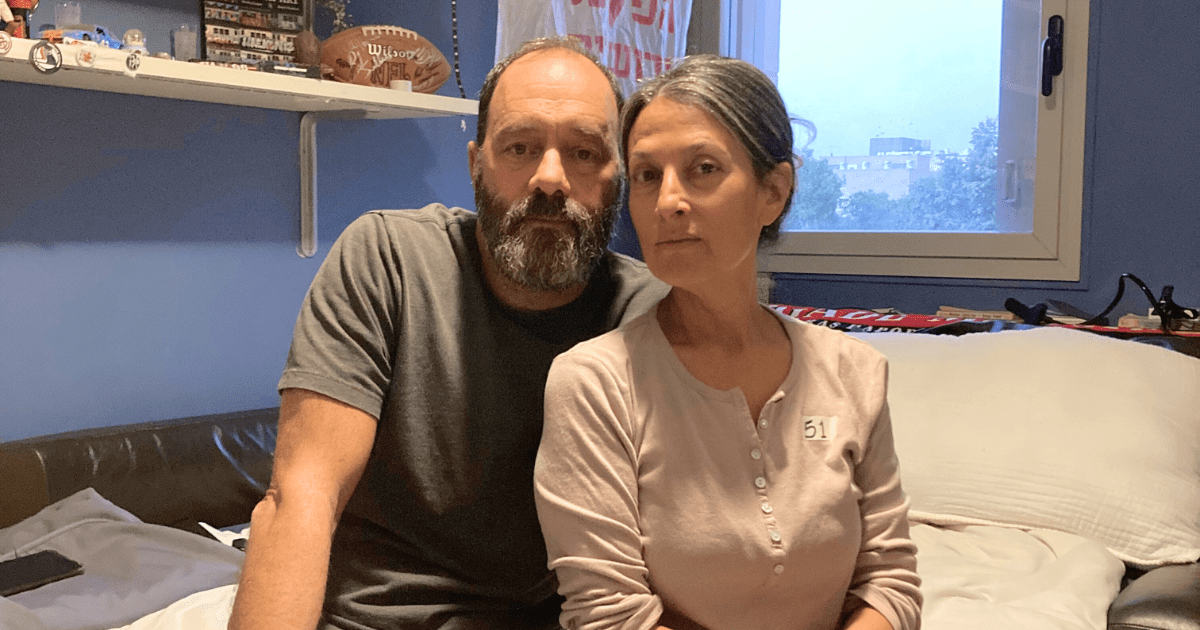

The parents of hostage Hersh Goldberg-Polin reflect on their ongoing agony.

Act TranscriptRachel Golberg: I go out on the porch on Friday nights and I scream the bracha (blessing) to him with my hands up in the air, and then I come in and we have this big, horrible picture that somebody gave us of him with his name spelled wrong, and it’s behind our front door. And I kiss his head and I smell his hair on the picture because I know what that smell is of his hair. And I just wait and crave for that time when I can smell his hair, you know. They just brought his bag back on Friday. They found his bag seven weeks later: that he had taken to the music festival. And when I unpacked it yesterday and I was taking out…now, normally we’re always like: “Hersh, you need to shower, my God, what is that smell?” And I was taking out his clothes, and I was finding the armpits and inhaling it like it was the most wonderful thing I could ever smell.

Jon Polin: This morning I went for the first time, this is day 51, I went to the above ground bomb shelter where Hirsch came under attack, lost his arm and was then taken captive. And as I was there, I was thinking: it’s so close, it’s like couple of kilometers from here, a mile and a half. Let’s just go right now, like my friend has a four by four. Let’s just go cut across the fields and go get him. We thought better of that, but it’s absolutely crossed my mind. I mean, he is so close.

Mishy Harman (narration): Hey listeners, it’s Mishy. So as you know, during these incredibly difficult days we’re trying to bring you voices we’re hearing among and around us. These aren’t stories, they’re just quick conversations or postcards really, that try to capture slivers of life right now.

Many of you have probably heard or read about Rachel Goldberg and Jon Polin, the parents of 23-year-old Hersch Goldberg-Polin, who was kidnapped from the Nova party. In many ways they’ve emerged as the face of the hostage families. They’ve met with Biden and the Pope. They were on the cover of Time Magazine. Rachel has spoken at the UN, and at the March for Israel rally in Washington, DC. And in all those places, as well as in countless other interviews, speeches and meetings, they’ve told the heartbreaking tale of the two text messages Hersh sent on the morning of October 7th , one saying: “I love you;” and the other: “I’m sorry.” He wrote those messages from within a shelter where he was hiding with 28 other party goers. Eighteen of them were killed, and Hersh, whose left arm was blown off, was badly wounded. Shortly thereafter, Hersh and three others from the shelter were loaded onto Hamas pickup trucks and taken into Gaza. It has now been 55 days. Earlier this week, Adina Karpuj and I sat in Hersh’s room and talked to his parents.

Rachel Golberg: I’m Rachel. I’m Hersh Goldberg-Polin’s mom.

Jon Polin: I’m Jon. I’m Hersh’s dad and Rachel’s husband.

Rachel Golberg: And I’m Jon’s wife. Who are you?

[She laughs]

Mishy Harman: And how would you have introduced yourselves on October 6th?

Rachel Golberg: I would have said “I’m Rachel.”

Jon Polin: Yeah, I guess I would have said “I’m Jon.” I’m proud to be the father of Hersh, Libby and Orly and Rachel’s husband and life partner, but I never used it as part of my identity, or never introduced myself with that identity. But I do find it more relevant, more present now than before.

Mishy Harman: What have you discovered about each other during this time?

Rachel Golberg: I really have discovered, even on the first night, we went into our room crying, saying we think he’s dead. I remember saying: “It’s going to be horrible for a long time, and then we’re going to be okay. One day, we’re going to be okay again…it’s not going to be the rest of our lives. And we were crying, and we were holding each other saying…one day we’ll be okay again.” And…this is the moment…I cannot imagine there is not one other person on the planet who I could go through this with, not one. And you have to be made of steel; a couple made of steel to get through it. And I’m very thankful. I daven every morning (I pray every morning), the first thing that I thank God for is for Jon. And there’s no way on earth, no way on earth, that I could do this without exactly him—not a strong partner, great partner, him, him, partner.

Jon Polin: And I’m not even sure that I learned anything new about Rachel. I do feel like I’ve shared her with the world. I walk down the street now and people stop me, and sometimes they say: “You’re Hersh’s dad, which is great, I’ll take that. And sometimes they say: “You’re Rachel’s husband,” which is also great, and I’ll take that. But the number of people who come up to me now and say: “Your wife is amazing, and I just find myself saying: “I know, I know, I’ve known that for a long time.” But now she’s very public, and a lot of other people also know that.

Rachel Golberg: Look, I think to be known for something horrible is horrible. So that makes me sad, because either I’d like to be anonymous, or it would be nice to be known for something wonderful, not something that’s everybody’s worst nightmare.

Mishy Harman: You’re now living a reality that you never imagined and never wanted to live. And you’ve been thrust into this role that I don’t think ever in a million years would have been one that you thought would have been part of your life. And what does it feel like to be in that role?

Rachel Golberg: The role of being the family of a hostage…that’s an indescribable place to be. We keep trying to describe it in different ways…sometimes I’ll say it’s like trying to talk to someone who was born blind and has never had vision, and trying to explain to them what purple is…but even that…it’s not pain, it’s something else. It is pain, but I mean, pain is the pshat (literal meaning of biblical text), pain is the…surface. There’s such a deep existential existence that’s mostly what’s challenging is that it’s an existence…it was explained to us that trauma is something that comes out of nowhere and it’s a shock and it’s earth shattering, and then you have to figure out how do I stand up and how do I take my first step forward. This is very different than that because it hasn’t hit us and moved on. It is a slow motion, stretched out, agonizing continual way of being.

Mishy Harman: What do your days look like now?

Jon Polin: Filled with action. We made the decision by Saturday afternoon, October 7th, that we weren’t going to wait around for the Israeli government, or the US government, or anybody else to take action on our behalf. We said: “We’re taking matters into our own hands.”

We set up a situation room, and sometimes there are four people here, sometimes there are 14 people here: it depends on the day and the time of day. But we are constantly in action mode—whether it be reaching out to US officials; reaching out to Israeli officials; finding foreign government officials that may be relevant players here, connecting with other hostage families to compare parts of the journey. We basically have said we need to tell the story, keep it front and center for the world, and we need to do everything we can to reach out to every influential person that we can that might ultimately be the person who could lead to the release of Hersh.

Rachel Golberg: He’s gonna hate it. All of his friends always say he is going to hate that he’s everywhere, that you guys are everywhere, that you know, that you’ve described him in all these articles and all these newscasts and all these things. We joke about it all the time. We say…first of all, God willing, I would love to deal with him hating it. Do you know what I mean: like he should come home healthy, soon alive, one arm down, we’ll deal with that; trauma, we’ll deal with it.

But honestly, my normal way of being when people say there’s fight, flight or freeze, I’m a freezer, usually. But I’ve never been in this situation before, and this is just primal what we’ve been doing. It’s not me. This is so not me to go and not be scared. Look, I’ll speak in public, it’s not that—I’m not shy—but I do get nervous. I’ve taught for years, and we joke about it because I’ll be going to teach a group of 16 year olds, like they’re not exactly like an intimidating bunch, and I’ll be nervous and shaking before, and it’s a whole big thing. That’s gone. I don’t care who I talk to now…like the scariest thing on planet earth has happened. So I don’t care getting up in front of 300,000 people in DC. My voice didn’t shake. I don’t care. I don’t care getting up in front of the UN; up in front of the Pope. I don’t care. And I’ve never been that type of person. In fact, we used to joke because the Polins they can’t ever sit still. They always have to be doing something. You go on a vacation, there’s no like hanging out by the pool with the Polin family. The Polins are doers. They’re like: what are we doing next, ba, ba, ba, boom. I am not like that. I am not wired like that; my family is not like that. And I would even say, I feel like people who do that are running from something. It’s like they don’t want a moment of silence, because they don’t want to do introspection, or they don’t want to sort of contemplate their lives, so they want to always be moving, then they never have to think. And now I really appreciate that way of being. We have to be doing something to help save Hersh’s life and hopefully the other hostages. And it also makes it so there isn’t time for that introspection, which at this moment would be soul shattering; it would be unbearable and excruciating.

I actually only feel comfortable physically when I don’t feel comfortable, like I don’t want to feel good, because I know he doesn’t feel good. So the second or third week, someone said…I’m having someone come, they’re going to give you a massage. It will just be 20 minutes. You can have your clothes on; you can just do whatever. It was so excruciating for me. I can’t do that now. I cannot do that. Now I can’t even taste good food. Like I eat food in order to have eaten, but when I feel hungry, that’s the only time I feel okay, because I feel…I don’t know if it’s guilty, I don’t know what it is…it does not feel appropriate to feel okay right now. It does not feel right. And so when I’m uncomfortable, when I’m going to sleep and my stomach’s growling, I feel good.

Jon Polin: We don’t exercise. We don’t take any time of our own. We just don’t. I keep saying: next week, next week, next week. And now we’re seven plus weeks in, and it hasn’t happened. Maybe next week.

Adina Karpuj: Have any specific memories of Hersh or stories about him, been in your mind a lot during this time?

Jon Polin: …When I think about stories about Hersh, the stories that I think about and the traits that I think about are seen through the lens of, how is that trait helping him navigate? So for example, when Hersh was 12, he came to us and said: “I have something really important to discuss with you guys.” So we were like: “Okay, let’s sit and have a conversation.” And he says to us: “I know I’m young, and you think that I’m not ready, but I’m really ready to move out and get my own apartment.” And we stopped ourselves from laughing, because we had to take it seriously, and we explained to him that he actually probably wasn’t ready. But he’s had this independence from the time he was literally, like two years old. And I keep saying that sense of strength and independence and independent thinking is a really strong attribute for what he’s going through right now. He’s gonna figure out a way to kind of keep pushing through this.

Rachel Golberg: I also am thinking that kind of thing. But when you ask the question of…you have this whole life of stories that you can be thinking of and drawing on, that I don’t allow myself to go to, never, because I think that it would break me. And I don’t go there.

Adina Karpuj: To memories, to stories.

Rachel Golberg: Nope, nope. I found one piece of paper that I made for him…. as a child he was obsessed with geography, and he would say to me: “Make me a test, make me a quiz, make me whatever.” And I found one of those quizzes, and it’s on my nightstand, and that’s the only thing that I’ve allowed myself to cheat and and go there, because the really yummy luxury of opening…like a photo album, or thinking about…because I have journals that I kept when the kids were little and reading vignettes, I think that it would break me right now. So I don’t do that. So to be constantly busy, and constantly running, constantly, it’s actually better. The only thing that’s sad is that when we do finally get into bed at night and take our pills that our doctor has given us to knock us out, because otherwise we couldn’t sleep, we always say to each other: “Well, I guess we failed, because he’s not home, they’re not home.” So, we worked our asses off, and you fall into bed exhausted, and you know that you failed. It’s the ultimate myth of Sisyphus. We wake up every morning and we’re like: “Okay, we’re back to square one.” It doesn’t matter what we did for 51 days, we failed, because here we are.

Mishy Harman: When you close your eyes and imagine Hersh just right now, what do you feel and what do you see?

Rachel Golberg: I try a little bit not to think about it. And sometimes I want to think: oh, he’s in a tunnel playing soccer with some of the little kids. And it’s a shame that he used to love to be the goalie. Now he has one arm, maybe that’s harder…when I’m in a good placeI want to picture that, and I don’t want to picture any of the bad that could possibly be happening, because it’s not helpful for me. It doesn’t help me do anything but suffer more. So I try not to really picture it. And I try to just hope and pray that he’s with other people, other hostages or other nice Gazan people, because I really feel that there are good Gazan civilians who are also going through absolute hell right now, and I am also convinced that there are many who know Hersh, or have seen Hersh, or know where he is, and I understand why they can’t say anything. I often—when I was young—would say to myself: What would I have done in WWII? Would I have hid Anne Frank? And I want to believe that I would have…and the truth is I probably would have been too scared. So I don’t blame the people who are too scared, who are there, but I’m hoping that they’re being kind to him, whoever he’s with, somehow, is being kind to him.

Mishy Harman: Do you ever have the fantasy of just getting into the car, and since it’s not that far away, just going to Gaza or going to pick up Hersh?

Jon Polin: Yes, I have that fantasy all the time.

Rachel Golberg: We actually have talked about doing that.

Jon Polin: Totally.

Rachel Golberg: And then we go to the border, and we were going to be like: “We are here, bring him out,” or, and threatening, right. Because I’m sure Hamas would take that. Like I was going to say: “I have had a great life. We’re going to trade now, okay, he’s coming out, I’m going in. Enough. Like as if they’d be like: “Oh, okay, somebody bring out Hersh.” But when we were going to the UN I was very apprehensive because I didn’t want to leave. Because I thought, at least I know that I’m like an hour and a half from him now, probably less. And I was really panicked to leave here and to be so far away from him.

Jon Polin: Well, when we travel now, we fly ElAl and on a flight just now, we got on, we talked to the captain and we said: “If they announced that they’re bringing out Hersh and the other hostages while we’re in the middle of the flight…” And he didn’t even let us finish the sentence, he said: We’re gonna turn the plane around and go back home.”

Rachel Golberg: And we were like: Oh, thank God.

You know, Hersh is my first child, so he is the person who changed my being in the world. I was a person, and he made me mother. So the girls, I’m also their mother, but I was mother before they showed up. He changed who I am in the universe, and he’s not here.

Mishy Harman: So we’re talking here in Hersh’s room on what will be the third day in which hostages are being released, thankfully. What’s going through your mind as you’re seeing this.

Rachel Golberg: Well, we’re thrilled. It’s such a feeling of relief and happiness, and we just pray that somehow the stamina keeps going, and the thread keeps holding, and that Hersh’s turn will come really soon.

Jon Polin: We’ve spent 51 days grasping anywhere for hope. So this is a great first step. In a world where you’re looking for hope anywhere, seeing a dozen or more people released day after day is really, really encouraging.

Mishy Harman: Rachel, Jon, thank you so much. And of course we’re with you in every way, in every prayer for Hersh’s return and everyone’s return and for quiet days to resume for all of us who live here.

Rachel Golberg: Amen, amen.

The end song is Tefilat Haderech (“The Traveler’s Prayer”) by Shai Tsabari.