Pinchas Rosen, or Felix Rosenblüth (as he was called in his youth), was born in Berlin in 1887, and grew up in a wealthy family on the Messingwerk estate, some 50 kilometers away. Like nearly all the other Jews in this enclave, Rosen was raised strictly Orthodox. He focused on piano and chess but lacked a true passion until, at the age of 16, a friend lent him a copy of Herzl’s novel Altneuland.

From that point on, Zionism burned within him. The goal of creating a utopian, egalitarian society in the Land Israel, as Herzl had imagined, became his life’s mission.

After being wounded in WWI, Rosen became Chairman of the Zionist Federation of Germany, and subsequently moved to Mandatory Palestine in 1923. There, he founded the mostly German-Jewish Aliya Hadasha Party and was elected as its representative to Moetzet HaAm. In fact, not only did he sign the Declaration of Independence, but it was he who commissioned the writing of the text from Mordechai Beham, a young Tel Aviv-based lawyer, in April 1948.

Following the establishment of the State, Rosen – a level-headed centrist – served as Minister of Justice in eight of Israel’s first nine cabinets. In addition, he turned down offers to be elected Israel’s President on not one, not two, but three separate occasions.

As a yekke, he was on the fringe of the mostly Eastern European political gestalt, but being Ben-Gurion’s close and trusted ally, meant that he played a major role in shaping the currently controversial Judicial Selection Committee, as well as the Supreme Court itself, which – during the first few decades of the State’s existence – was heavily populated by those capable of properly pronouncing an umlaut.

Throughout his time in office, he sought to advance a progressive agenda, seeking to strip the rabbinical courts of their judicial power, and pushing, repeatedly, for Israel to adopt a constitution.

When he retired from the Knesset in 1968, he lamented the lack of a single binding document, noting that it would “serve as a blockade against extreme expressions of parliamentary authority.”

In 1973 he was awarded the Israel Prize for his contributions to Israeli jurisprudence, and five years later, in May 1978, he passed away at the age of 91.

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: there were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

Today we’ll meet Pinchas Rosen, and his only living grandson, Nick Ross. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Act TranscriptNick Ross: My grandfather didn’t marry women, women married my grandfather. He was obviously quite attractive to women, not least my own grandmother, who used to go out with his brother, Martin, and then switched to Felix at some stage.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s seventy-five-year-old Nick Ross, a celebrated BBC presenter, who – in 2021 – was named a CBE (a Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in recognition of his journalistic achievements, his long-standing involvement with local charities and his pioneering crime prevention activities. And for all you non-anglophiles out there, a CBE? Is a big deal.

For years Nick hosted popular TV and radio shows, made documentaries and championed causes ranging from road safety to drug addiction, from bioethics to healthcare.

Here, however, Nick isn’t talking about data-driven approaches to crime reduction or science education (which, by the way, is another of his pet causes). Instead, he’s talking about Israel’s first Minister of Justice, Pinchas Rosen, who just so happened to be… his grandpa.

[Signed, Sealed, Delivered? introduction]

Today we’ll meet Pinchas Rosen, and his only living grandson, Nick Ross. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Here’s our producer Jamal Risheq with Nick Ross, Pinchas Rosen’s grandson.

Jamal Risheq (narration): A lover of classical music, an enthusiastic chess player and an avid reader of Goethe, Israel’s first Justice Minister Pinchas Rosen was the quintessential yekke, or German-born Jew. To a large extent, and perhaps more than any other signatory of the Israeli Declaration of Independence, he was the true ideological heir of Theodore Herzl.

Felix Rosenblüth, as he was called in his youth, was born in Berlin in 1887, and grew up in a wealthy family on the Messingwerk estate, some 50 kilometers away. Like nearly all the other Jews in this enclave, Rosen was raised strictly Orthodox. He focused on piano and chess but lacked a true passion until, at the age of 16, a friend lent him a copy of Herzl’s novel Altneuland.

From that point on – his biographer, Ruth Bondi, wrote – Zionism “burned contagiously” within him. The goal of creating a utopian, egalitarian society in Israel, as Herzl had imagined, became his life’s mission.

He married Annie Lesser, his older brother’s girlfriend, and served in the German Army in the First World War, and – on May 2nd, 1915 – was wounded in battle on the Eastern front. Lying face down in the mud, he noted to himself that he might yet die on the fifty-fifth anniversary of Herzl’s birth.

He survived, however, became Chairman of the Zionist Federation of Germany, and subsequently moved to Mandatory Palestine in 1923. But his wife and the mother of his two children refused to follow suit. Annie, a free-spirited jewelry maker and puppet theater producer, visited once, in 1924, and promptly decided the Levant simply wasn’t for her. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, she took their kids, Hans and Dina, and moved to London.

Rosen – in the meantime – fell in love with a friend of hers, Hadassah Perlman, the founder of a successful Yemenite-style embroidery business called Shani. After some back and forth, Felix and Annie got divorced, just in time for him to marry the already-pregnant Hadassah. Their daughter Rivka died of cancer at the age of seven. Upon her passing, Rosen wrote to a friend, quote, “life goes on, but its glow has been extinguished.”

His wife, Hadassah, died three years later.

Though Rosen got married for a third time in 1950, this time to Johanna Rosenfeld, he regularly visited Annie, Hans and Dina, in London.

As a politician, he founded the mostly German-Jewish Aliya Hadasha Party and was elected as its representative to Moetzet HaAm. In fact, not only did he sign the Declaration, but it was he who commissioned the writing of the text from Mordechai Beham, a young Tel Aviv-based lawyer, in April 1948. You’ll be able to hear all about that in an upcoming episode in the “Signed, Sealed, Delivered?” series.

Following the establishment of the State, Rosen – a level-headed centrist – served as Minister of Justice in eight of Israel’s first nine cabinets. In addition, he turned down offers to be elected Israel’s President on not one, not two, but three separate occasions.

As a yekke, he was on the fringe of the mostly Eastern European political gestalt, but being Ben-Gurion’s close and trusted ally, meant that he played a major role in shaping the currently controversial Judicial Selection Committee, as well as the Supreme Court itself, which – during the first few decades of the State’s existence – was heavily populated by those capable of properly pronouncing an umlaut.

Throughout his time in office he sought to advance a progressive agenda, seeking to strip the rabbinical courts of their judicial power, and pushing, repeatedly, for Israel to adopt a constitution.

When he retired from the Knesset in 1968, he lamented the lack of a single binding document, noting that it would, quote, “serve as a blockade against extreme expressions of parliamentary authority.”

In 1973 he was awarded the Israel Prize for his contributions to Israeli jurisprudence, and five years later, in May 1978, he passed away at the age of 91.

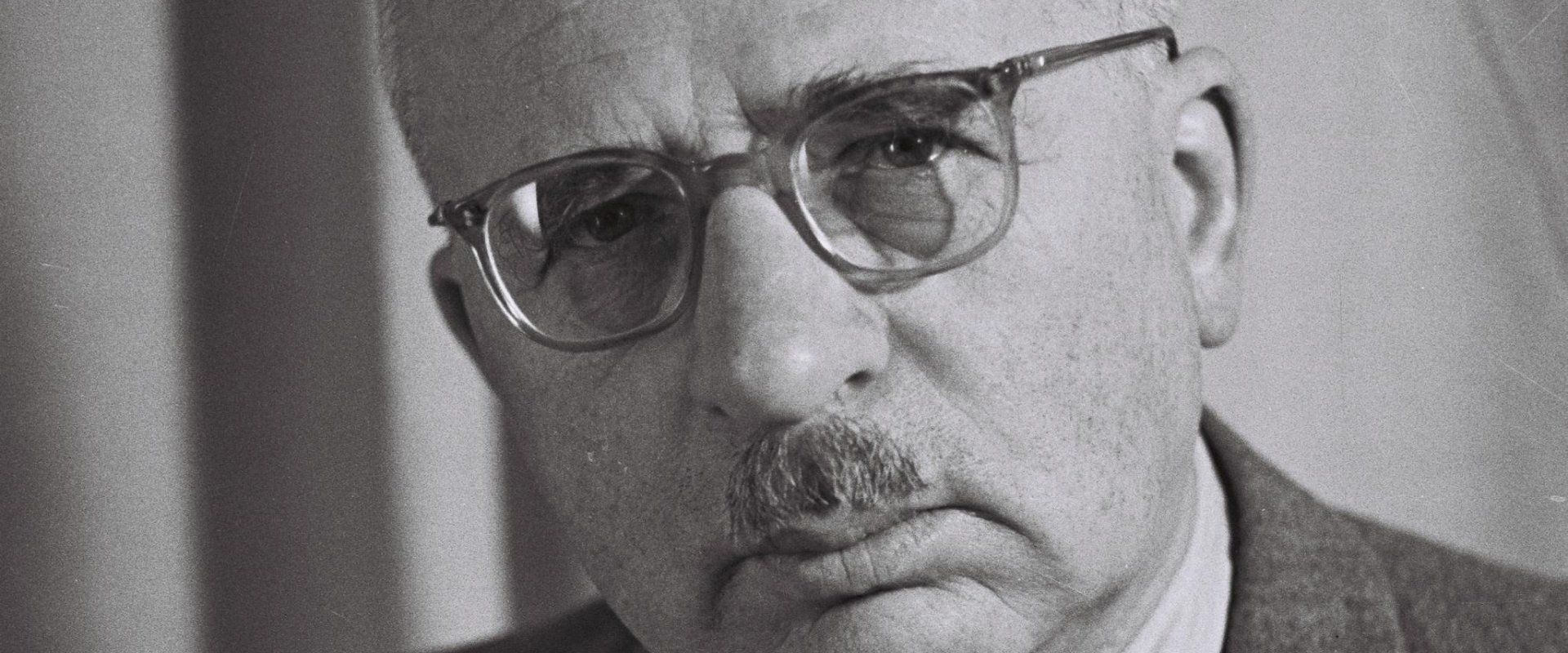

Here he is, in an interview for the State Archives, discussing his vision for Israel’s future.

Pinchas Rosen: I’d like to hope that we will do everything possible in order to fulfill the vision of Herzl, who didn’t want the State of Israel to be like all other states, but rather an exemplary state – culturally, socially and civically.

Nick Ross: Felix my grandfather came from a highly orthodox religious background. And one of the challenges was that his generation was moving away from that, was becoming much more secular. Certainly much less orthodox. And I think that was a difficulty within the family. And his politics, I suppose, became a new religion. I know he was profoundly moved as a teenager — when he was a student — by the Dreyfus Affair. And I think that that’s what crystallized Zionism for him and made him become such a leader of student Zionism in Germany. I’m pretty sure that his whole life had really been geared to that Declaration of Independence. Ever since he was a middle teenager, certainly a late teenager, he had wanted to establish a Jewish State. He had wanted to establish it in Palestine and not in Uganda or anywhere else. At the first chance he could, he emigrated personally to Palestine, even wrecking his marriage in doing so because his wife, my grandmother, really didn’t want to stay there. She found it too hard going at the time. When he first went to Israel he was a lawyer, he was trying to help migrants, particularly those who came from Europe to settle into Palestine. Everything he had been working for was that Declaration. So I think for him, it must have been an extraordinary, profound moment of achievement and excitement. Given that my grandfather lived in Israel and I lived in London, obviously I didn’t see him very often as a child. Every year we got something which in postwar Britain was really exotic – he would send us a case of Jaffa oranges. And every couple of years my parents would go out to Israel to see him. When I first went to meet him in Israel, I was ten-years-old, came down the steps of the aircraft and there he was to meet me, with a chauffeur-driven limousine. Incidentally, it was years before I realized everybody wasn’t met at the bottom of the stairs by their grandfather in a limousine. I was astonished driving from the airport up to Jerusalem past all the burned-out tanks and armored vehicles which had been left there as a memorial to the war, intrigued by the fact that he was obviously very, very important. As a child, you know, I’m not even sure I was aware that he was one of the original signatories of the Declaration of Independence. I was very conscious that he was a liberal in every sense. That is, he believed in a liberal social environment, he believed in a liberal economy. But I was never conscious that he was actually one of the signatories to the Declaration. He was much more my granddad than he was a political or historical figure for me. He was just a close relative, and one who seemed to have a rather awesome job. He did try to get to London every couple of years or so. I remember once we went to a funfair, and I remember my grandfather pressing a sixpence into my hand and saying “go and enjoy yourself for the day.” Well, before the war sixpence perhaps might have lasted you a whole day at a funfair. Sixpence would barely do one ride at the time. And obviously he hadn’t kept up with the inflation that had been going on over the last ten or twenty years. And it was slightly embarrassing because my, you know, my friend thought he was terribly mean, and of course he wasn’t at all, he was a very generous man. But he just wasn’t aware that you didn’t buy much for sixpence, six old pence, that was, in England in the 1950s or 60s. He was a nice guy, we would say in English, a nice bloke, a mensch. So it was a relationship which was yes, warm, but slightly, slightly distant. None of the family (immediate family) left now live in Israel. When we’d go, we’d just go as tourists. Of course, we feel a sense of affinity, but not a sense of personal identification. If I was going to emigrate from the UK, where would I think of going? Israel would not be immediately top of my list. I mean it might be somewhere I’d think of going but it’s not a close affinity for me, and I think my grandfather would, he wouldn’t be surprised. I don’t think he’d be disappointed. His grandfather would be deeply disappointed that Felix wasn’t ultra-orthodox Jewish. Each generation makes its own way. He was religious in the sense that he would observe religious ceremonies, but I think as much for show as anything else. I think the religion he had as a child had pretty much left him. And although he would behave like a good Jew when he was in Israel, he would eat bacon and pork sausages when he came to London. So he was, for all intents and purposes, really secular himself. I think everything that he worked for, both as a lawyer and a politician, was about civil liberty, was about decency. And I think he wanted to establish, well I know he wanted to establish the State of Israel, not as an exclusively Jewish state. He was always adamant that this was a state that was for everybody, including and particularly including Arabs. When I read the Declaration, I’m impressed by several of the paragraphs. There isn’t, though, any acknowledgement of how any population on Earth would feel when there’s massive migration of people who seem to them alien, coming from Western and Central Europe, coming from Russia, coming from America, into what they regarded, it was called Palestine, and they regard it as Palestinian lands. We only need to look at countries now, today, to see how populations are rising up, against migration, against at any rate immigration. And there’s nothing in that Declaration, which acknowledges what it must have felt like, had you been an Arab, had you been Palestinian living in Palestine, now to find yourself in a Jewish state. It’s a challenge. And it’s a challenge that is omitted, at least in direct language, from the Declaration of Independence. With hindsight, that’s perhaps a shame. I think he’d feel a bit bittersweet about Israel. Bear in mind, he was quintessentially a liberal. And indeed, with a capital L, the party he led was the Liberal Party, and I think he’d be slightly disconcerted by the right-wing and very aggressive, rather militaristic stance that Israel has taken, perhaps unsurprisingly, because it hasn’t established a permanent peace and friendship among its immediate neighbors. And that perhaps has naturally driven the population to feel more defensive and therefore more assertive or more nationalistic. I’m certainly not right-wing as a politician myself. I’m not in tune with the settler movement and the really rather aggressive side of Israel. And I deplore it, I don’t like it. But having said that, I think Israel has been a phenomenal success. I really do. Let’s look around the world. I mean, Israel is one of the most settled democracies on the planet. It is stable. It has a great deal of integrity and honesty. There is genuine internal democracy. It’s a rowdy, difficult, cantankerous democracy, but then all thriving democracies are. I’m pretty confident it will survive. And if it didn’t, although I don’t live there (I have very tenuous connections indeed with Israel, other than through my grandfather and his generation) and even though I’m already well into my 70s, I’d probably go and fight for it myself, actually.

In 1961 Eliezer Whartman of the Israel State Archives conducted a series of interviews with 31 of the 37 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. For the full interview with Pinchas Rosen, see here.

The full text of Ruth Bondi’s 1990 biography of Felix Rosen: Pinchas Rosen and His Time (Hebrew) is available on the Ben-Yehuda Project Website.

For a shorter version of that biography, including dozens of pictures of Rosen’s parents, siblings, wives and brothers-in-law (and even one of the future Israeli Minister of Justice in his Prussian officer’s outfit), see the TLV Streets Project.

For an analysis of the influence of the yekkim, or German-born Jews, on the culture and formation of Israeli law, see Eli Salzberger and Fania Oz-Salzberger’s 1998 Haifa University Law Review Article, “The German Tradition of the Israeli Supreme Court” (Hebrew). It is there that they mentioned the matter of umlaut-pronunciation as the determining factor for who ought to be considered a yekke.

The National Library of Israel has a wonderful hour-long recording of Rosen discussing his childhood and university days.

For an excellent recap of the Lavon Affair, see this Israel Democracy Institute article. In short, the 1954 Lavon Affair, which came to a head with the 1961 resignation of Prime Minister Ben-Gurion, was a line in the sand of Israeli politics, and marked the start of the decline in the hegemony of the Labor Party. The affair itself revolved around Israel-initiated terror attacks in Egypt, which, in turn, were meant to induce the British to retain their control over the Suez Canal. Justice Minister Pinchas Rosen, who headed the “Committee of Seven” that looked into the affair, concluded that it was not Defense Minister Lavon who gave army intelligence the order to act. This caused an irreconcilable rupture between Rosen and Ben-Gurion.

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubber is Leon Feldman.

The end song is Habib Galbi (lyrics and music – Traditional Yemenite Folk, arrangement – Tomer Yosef), performed by A-WA (Tair Haim, Liron Haim & Tagel Haim).

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.