In different ways, we are all constantly searching for a place to call home. For some that home is physical, for others it’s spiritual, or intellectual, or communal. And no time of year spotlights that search more than the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, when we are literally commanded to leave our permanent homes and build new, temporary dwellings. So at a moment in history when so many people around the world – from Syria to Afghanistan to South Sudan – are leaving their homes and trying to grow new roots, we set out to explore the idea of making a home.

Mishy Harman follows schach, or palm tree branches, all the way from a Jordan Valley date farm to Jerusalem’s ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Me’a Shearim and Tel Aviv’s Yarkon Park. Along the way, he talks to a rabbi, a farmer and a gardener about building a sukkah.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Analia Bortz from Jerusalem is one of those people who seems to have lived multiple lives.

Analia Bortz: I grew up in Argentina, we made aliyah a year ago.

Mishy Harman (narration): She’s a medical doctor.

Analia Bortz: And I’m a bio-ethicist.

Mishy Harman (narration): And she’s also (and this was the reason for our chat) a rabbi. In fact, she told me, she was…

Analia Bortz: The first female rabbi in South America, ordained in 1994.

Mishy Harman: [Laughs]. That’s quite a list of things to be.

Analia Bortz: Ah yes, but actually today my passion is just to take care of the family, to indulge my granddaughter, to do a lot of art, and to study archeology.

Mishy Harman: Oho!

Analia Bortz: Yeah, I’m enjoying it.

Mishy Harman: Alright, so we are just about to celebrate Sukkot and can you explain a little bit what Sukkot is all about?

Analia Bortz: So Sukkot is a wonderful holiday. It’s the relationship with the land. This sense of belonging without being anchored in a place. So for seven days we go out of our permanent homes, and we live outside our permanent homes. Basically it’s a little bit of how the Jewish people are, in our history. We just pick up our ohalim, our tents, and we just move to another place.

Mishy Harman: And what exactly is a sukkah?

Analia Bortz: So sukkah is a non-permanent structure. According to the Talmud has to have at least two-and-a-half non-permanent walls, with a schach which is the roof that you can see the stars from there.

Mishy Harman (narration): That schach – the roof – is often made out of kapot tmarim, the branches of palm or date trees. They are, therefore, a key component of any respectable sukkah. Which is why many municipalities, including Tel Aviv’s, give out schach for free.

Mishy Harman: Hi! What are you doing exactly?

Avi Goldenberg: Ehhh… Going to make with my children sukkah, and I’m bringing the roof of the sukkah.

Mishy Harman: The schach.

Avi Goldenberg: The schach!

Mishy Harman: And this is all for free here? The municipality gives it for free?

Avi Goldenberg: Yes, yes. It’s a free.

Mishy Harman: Where do you live?

Avi Goldenberg: I’m living in Netanya. But I’m working in Tel Aviv, I’m a gardener. Also in Netanya they giving free.

Mishy Harman: So how many branches are you taking?

Avi Goldenberg: I took ten.

Mishy Harman: That’s enough for you?

Avi Goldenberg: Yes. It’s a little one. A little sukkah.

Mishy Harman: OK, [In Hebrew] Happy holiday!

Avi Goldenberg: [In Hebrew] Happy holiday! Thank you.

Avi Goldenberg: Thank you to [In Hebrew] the Tel Aviv municipality.

Mishy Harman (narration): But in Jerusalem and a bunch of other places around the country, the schach market around this time of year is booming. Most stands ran out within a few hours, and as the holiday neared the prices started to climb from six shekels to seven shekels, to a whopping ten shekels per branch. With prices like that, I decided to go straight to the source – to the Jordan Valley, not far the northern tip of the Dead Sea, where I met up with fifty-two-year-old Dror Sinai.

Mishy Harman: Hi Dror, nice to meet you.

Dror Sinai: Hi, nice to meet you too.

Mishy Harman: Where are we?

Dror Sinai: We are here in Tzomet Almog in my dates field, near Jericho. I live in the settlement over here, Vered Jericho. This is my dates.

Mishy Harman: So you grew these trees from zero?

Dror Sinai: Yeah. I was the one…

Mishy Harman: There was nothing here?

Dror Sinai: Nothing.

Mishy Harman: How did you get into this business?

Dror Sinai: It’s something that burn in my veins. That I feel that I want to be an agriculture. I know only to grow dates. This is the only thing that I know how to deal with.

Mishy Harman: So now is date season?

Dror Sinai: Yeah. This is the date season. Now we are picking the fruits, I can tell you it’s a celebrate, for me. You know, it’s something that cause you a lot of happiness.

Mishy Harman: Wait, so these guys over here are picking the fruit.

Dror Sinai: Yeah.

Mishy Harman: And these ones over here?

Dror Sinai: They are cutting the leaves.

Mishy Harman: And this is for Sukkot?

Dror Sinai: Yeah, this for Sukkot. There’s a guy that come to take this leaves from me and you can find it after it in Mea Shearim and yeshivas in Jerusalem.

Mishy Harman: And do you make more money on the fruit or more money on the leaves?

Dror Sinai: I’m not making money from the leaves.

Mishy Harman (narration): Turns out this is a perfectly timed and mutually beneficial situation.

Dror Sinai: I need to cut it anyway. I need to…

Mishy Harman: Why?

Dror Sinai: Because the tree supposed to grow up. And the leaves that are become to be brown, it’s become to be useless. The tree don’t need them. So it’s a win-win situation between the holiday and the farmers and everything and it’s… It’s for me, I’m also happy to do it for people in Israel that they can enjoy also from the schach that came from the dates that I’m growing.

Mishy Harman: And you also take some home your own sukkah?

Dror Sinai: Yeah, yeah. I’m taking a lot, something like two hundred because I have a big sukkah in my house.

Mishy Harman: Two hundred branches?

Dror Sinai: Yeah, yeah. Yeah.

Mishy Harman: So what’s your sukkah like?

Dror Sinai: It’s a big one. All the family come in Sukkot to our sukkah from all over the country, so it’s a big one. It’s something like twenty meters sukkah that we build every year.

Mishy Harman: [In Hebrew] OK, thanks so much Dror. Happy Holiday.

Dror Sinai: [In Hebrew] Happy Holiday.

Mishy Harman (narration): So If Dror is looking forward to hosting his large family, for Analia it’s all about…

Analia Bortz: The guests. Every single night there is another guest.

Mishy Harman (narration): By “guests” she’s referring to the kabbalistic tradition of welcoming ushpizin – or symbolic guests – into the sukkah.

Analia Bortz: Who are you going to bring tonight? Are you going to bring Sarah, Rivkah, Rachel or Leah, or are you going to bring Golda Meir or, you know, or Shulamit Aloni? So, that sense of, you know, there’s always room for someone else to come to the sukkah. Sometimes it’s more intellectual oriented, sometimes it’s just fun and there’s a lot of singing. For sure [Sings].

Mishy Harman: [Laughs]. And is a sukkah supposed to be our new, temporary home?

Analia Bortz: So, it’s a home that is a temporal home. I think that basically that’s a nice analogy to life, right? That means like life is temporal home, right? That’s who we are. Yeah.

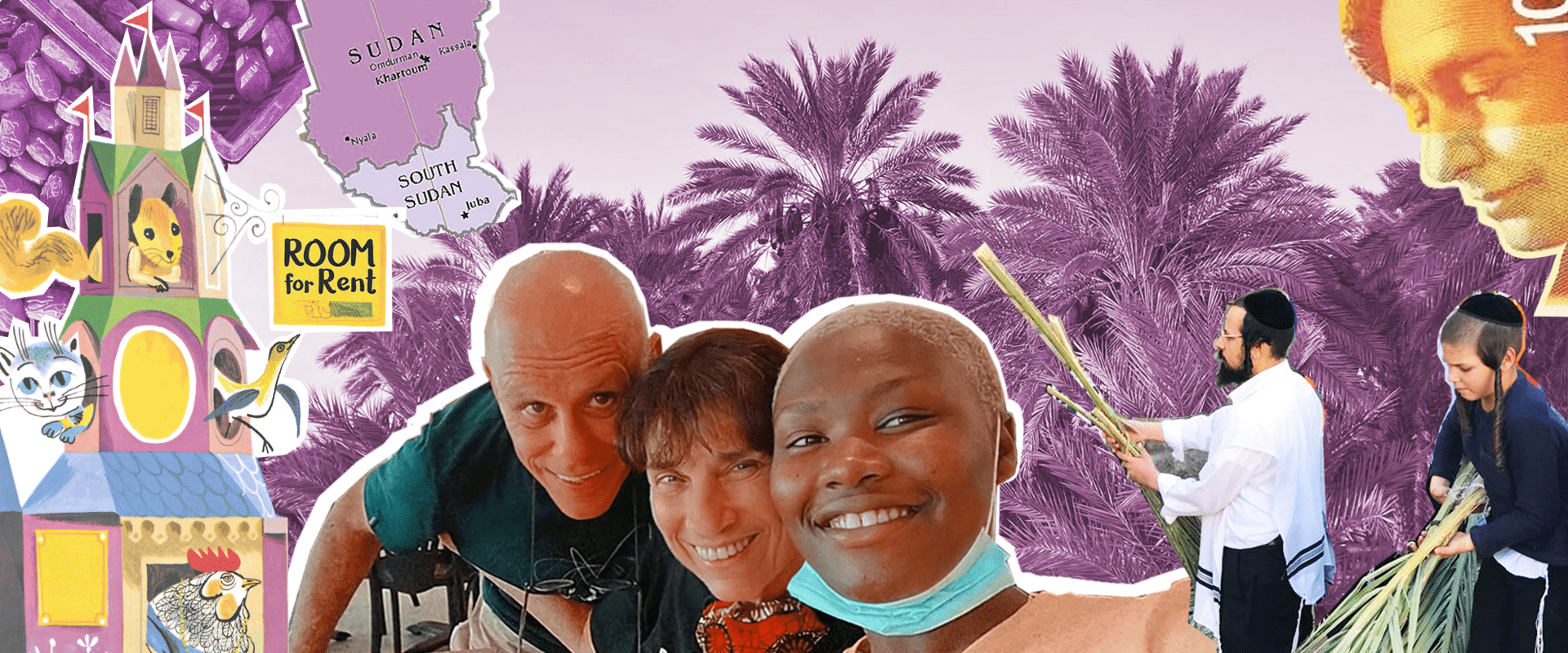

Mishy Harman (narration): Hey, I’m Mishy Harman, and this is Israel Story. Israel Story is brought to you by Tablet Magazine and the Jerusalem Foundation. Our episode today – No Place Like Home. We’re going to hear two very different stories – one about a popular Israeli children’s book and the other about a South Sudanese asylum seeker. But both of them are, deep down, about the same thing – making a home.

Alright, Act One: Room for Rent. Leah Goldberg is one of the most celebrated women in Israeli history. Heck, she’s even on the new one-hundred shekel bill. She was born a hundred-and-ten years ago, in the Prussian city of Königsberg, which nowadays is Kaliningrad, in Russia. And she died of cancer – in Jerusalem – at the age of fifty-eight. She was an author, a poet, a playwright, a critic, an editor, a columnist, a translator, a teacher and a beloved professor of comparative literature. Even though she’s been dead for more than half a century, she somehow manages to live on, discovered and rediscovered by each new generation of Israelis. And why, you might wonder, does that happen? Well, it’s due – in large part – to what’s probably her most enduring legacy – the children’s book Dira LeHaskir, or Room for Rent. Dira LeHaskir is a classic; one of the most popular Israeli children’s books of all time. Goldberg first published it in 1948, and it’s since gone through three editions and countless reprintings. It’s been translated into many languages, including – only surprisingly recently – into English. Now, as you might know, I became a father ten months ago. And I’ve been spending a lot of time reading books to my little daughter Hallel. I try out different voices, try out different styles, try to make her laugh. And whenever I get stuck, whenever I stumble, I channel my inner Yoni Yahav. Yoni is a dear dear childhood friend of mine. He lives in Jerusalem, teaches Hebrew to Palestinian students in East Jerusalem, and is finishing up a PhD at the Hebrew University, in Arabic literature. But the reason I channel my inner Yoni, is because when we were kids, Yoni had a side gig – an amazing side gig, actually – as a cartoon dubber on TV. He was, and remains to this day, the best maker of voices I know. So we asked Yoni if we could join him as he read this classic bedtime story – Room for Rent – to his two daughters, six-year-old Maayan, and four-year-old Yasmin.

Leah Goldberg is one of the most celebrated women in Israeli history. Heck, she’s even on the new 100-shekel bill. She was born 110 years ago, in the Prussian city of Königsberg (nowadays Kaliningrad, Russia), and died in Jerusalem at the age of 58. She was an author, a poet, a playwright, a critic, an editor, a columnist, a translator, a teacher and a beloved professor of comparative literature. Even though she’s been dead for more than half a century, she is rediscovered anew by each subsequent generation of Israelis. And that is due, in large part, to what is perhaps her most enduring legacy: the children’s book Dira LeHaskir, or Room for Rent. The book is a classic; one of the most popular Israeli children’s books of all time. Naomi Schneider and Skyler Inman joined Yoni Yahav as he read Goldberg’s masterpiece – in its new English translation – to his two daughters, 6-year-old Maayan and 4-year-old Yasmin.

Act TranscriptYoni Yahav: OK, so come sit next to me, Maayanush.

Maayan Yahav: I’m coming!

Yoni Yahav: Come, love. Come, chuk.

Yoni Yahav (narration): Alright, Room for Rent, by Leah Goldberg. In a sunlit valley between meadow and sky, stands a fine old house that’s five storeys high. On the first floor is a cornish hen, heavy and stout. All day long she lazes about. Our friend Miss Hen is so fat and coddled, she can barely manage a walk or waddle. On the second floor lives a cuckoo bird. Her chicks are all scattered, you may have heard.

Maayan Yahav: Cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo! [laughs].

Yoni Yahav (narration): From dawn to dusk, she makes her rounds to visit her children in other towns. On the third floor is a cat who’s finickly clean. She combs her whiskers so pristine, with fur that’s darkest midnight black, and a bow around her neck – she’s vain about that.

Maayan Yahav: What’s vain?

Yoni Yahav: Uhhh.. Someone who’s a bit shallow, just thinking about the outside, the way he looks. So she is a little bit vain.

Yoni Yahav (narration): On the fourth floor lives a tranquil squirrel with her friends she’s never picked a quarrel. She cracks pecans to her heart’s content and says, “this piece is heaven sent!”

Maayan Yahav: Kcho, kcho, kcho.

Yoni Yahav (narration): Up on floor five lived Sir Reginald Mouse, until one week ago, when he left the house. And to this day, we have our doubts that anyone knows his whereabouts. The committee got together and drew up a sign, in large block letters, in one straight line. They hung the sign on a nail on the door. It read…

Maayan Yahav: “Room for… for rent.” Not one word more.

Amia Lieblich: It’s really amazing how Leah Goldberg was able to express herself for children. I think she had very strong little child inside her. My name is Amia Lieblich. I’m a professor emerita from Hebrew University of Jerusalem. And as a first year student at the Hebrew University, I had the honor of participating in a big class of Leah Goldberg, where she was teaching foreign literature. She was fascinating, and she could talk without any notes, and quote different world literature by heart. She had a very heavy voice, out of – I think – many, many years of smoking. And she smoked in the classroom, all the time one cigarette finished another one. And the room was always full of smoke. It was amazing. Because on the one hand, she was such a serious author and scholar. And you may think that a woman like that will be very far away, in her ability to express herself to children. And she had no children of her own. But one of her most famous book is a Room for Rent. I have three children and four grandchildren. I read the book to my children, who are already in the midlife, and I read it to my grandchildren, and they know by heart.

Yoni Yahav (narration): By highway and byway, past hills and down dales, new tenants came knocking and telling their tales. First was Miss Ant. She marched up to floor five.

Maayan Yahav: [Stumping noise]. When she walks. [Stumping noise].

Yoni Yahav (narration): Opened the door and peeked inside. The neighbors all gathered around to spy as Miss Ant checked the place with a critical eye. They asked her politely if the rooms were all right. Perhaps she would like to stay for the night? “Are the rooms nice?” “Yes, they’ll suffice.” “Will the kitchen do?” “It’s just right, too.” “Do like the hall?” “It’s fine, that’s all.” “So come live with us, Miss Ant!” “I can’t.” “Why not?” The aunt replied in a nasty gripe. “Sorry, but the neighbors are not my type. A hardworking ant can hardly reside with a lazy hen whom she cannot abide. The Miss Hen in this house is so fat and coddled. She can hardly manage a walk or a waddle.” The hen was hurt and turned her back.

Maayan Yahav: Pacak.

Yoni Yahav (narration): Miss Ant went away. No need to unpack. As soon as she’d gone in bounded Miss Rabbit.

Maayan Yahav: Jumpy, jumpy.

Yoni Yahav (narration): She bounced up the stairs as was her habit. She read the sign and took a long look. Her soft furry ears quivered and shook. The neighbors all gathered around to spy as the rabbit checked the place with the critical eye. They asked her politely if the rooms were all right. Perhaps she would like to stay for the night. “Are the rooms nice?” “Yes, they’ll suffice.” “Will the kitchen do?” “It’s just right, too.” “Do you like the hall?” “It’s fine, that’s all.” “So Mrs. Rabbit, please stay.” “No way, I’m sorry,” she gasped. “But to make it short. The neighbors are simply not the right sort. How could a mother with twenty young ones live with a cuckoo who abandoned her sons? The cuckoo’s chicks sleep in other moms’ nests. She abandoned each one along with the rest. What kind of example is she for my brood? Don’t beg me to stay. I’m not in the mood.” The cuckoo bird stalked out in a huff. Mrs. Rabbit raced off. She’d had more than enough.

Ilan Greenfield: It was as if someone gave me a piece of gold, and I looked at it and I said, “nah, I’m not going to take it.” My name is Ilan Greenfield, and I’m the owner of Geffen Publishing House. Thirty-some years ago when we received the proposal to publish Room for Rent in English. So I looked at the book, I looked at the proposal, they wanted a lot of money to publish it. I said, “you know what, forget it.” I almost didn’t know what Room For Rent was. There is almost no Israeli child who grew up in Israel, who hasn’t grown up on this book. Although I grew up in Israel, and I was born here, I was born to an American father and a Czech mother. My mother was a Holocaust survivor, she barely went through – I think – fifth or sixth grade. They spoke English together, so our literature was not really Hebrew books. And the period I grew up in, my parents were struggling to make a living. I don’t think they had the time to read books to us. I can’t say I grow up on it. Maybe twenty-five or thirty years went by. And in one of those rare moments, when I clean up all the paperwork in my desk, I saw this contract, and I said, “wow, I can’t believe they offered me to publish Room for Rent. And what I really can’t believe is that I refused! How stupid could I have been?” It is just unbelievable to me. And I thought to myself, ‘well, should I throw it out or should I call them up?’ And I said, “there’s no chance no one published it.” I mean, thirty years is a long time. It’s a book that sold hundreds of thousands of copies in Israel. I said, “you know what, let me try.” I picked up the phone, called them up, and he said, “actually, we published in many languages, and we’ve never published in English.” And I said, “I want to publish it.”

Yoni Yahav (narration): With Mrs. Rabbit gone in came Snortimus Pig, in a pork-pie hat and a curly wig. He read the sign “Room for Rent,” tumbled inside and up he went. His tiny eyes peered at the ceiling and floor, the windows and walls, while he stood at the door. The neighbors all gathered around to spy as the pig scanned the place with the critical eye. They asked him politely if the rooms were all right. Perhaps he would like to stay for the night. “Are the rooms nice?” “Oh yes, they’ll suffice.” “And the kitchen, what do you say?” “Far too clean, but OK.” “Do you like our hall?” “It’s fine, that’s all.” “Then, Snoritimus, will you remain?” “Heavens no, I must complain! The neighbors are not to my taste, I’m afraid. There’s been a huge error, a mistake has been made. Me in the same house as a cat with black fur? A white thoroughbred pig cannot live next to her.” The neighbors did not remain silent for long. “Get out of here, pig!” they cried, “scoot, run along. You’re the mistake. You’re the one who’s all wrong!” “Goodbye!” grunted Snortimus, tossing his tail. Then in waltzed the honey-voiced nightingale. The nightingale sang a melodious song. As she flew up the staircase, it didn’t take long. She read the sign and opened the door, examined the walls, the ceilings, the floor. The neighbors all gathered around to spy as the nightingale gazed with the critical eye. They asked her politely if the rooms were all right. Perhaps she would like to stay for the night. “Are the rooms nice?” “Yes, they’ll suffice?” “And the kitchen will do?” “It’s just right, too.” “Then stay with us, please.” “No, I won’t stay or ask for the keys. The neighbors are dreadful, as everyone sees. How can I enjoy my peace and quiet, when the squirrel downstairs is creating a riot? She cracks those nuts the whole day through. The noise is worse than in a zoo! My delicate ears need a beautiful tune, not a squirrel-some racket that makes me swoon.” The squirrel flinched and took offense. The nightingale flew off over the fence.

Yoni Yahav: Squirrel was a little bit offended.

Maayan Yahav: What’s offended?

Yoni Yahav: He felt sorry about himself, he was a little bit sad, because she was saying bad things about the noise he makes.

Jessica Sitbon: I love languages. Languages are part of my soul. OK, my name’s Jessica Sitbon. And I am a translator from Hebrew into English. You know, this book is really… it’s canonic in Israeli culture, not just for children today, but you know, anyone who was raised in Israel and even people that were raised abroad. I mean, as a Jew growing up in San Antonio, Texas, my parents had this book, because they wanted me to learn Hebrew as a kid, and my Israeli aunt sent us a copy of this book. So I was familiar with the book, even as a kid, and we’re talking, you know, like fifty years ago. Ilan offered me the opportunity to translate this book. And it was very exciting, I jumped at the chance. First, I just read the book and tried to absorb the feeling of the language. Then I’ll try to think how can I render this in English. At a certain point, I… I stopped worrying about being true to the original and really think about how it sounds. So purists might take issue but I think it’s successful. I hope that Leah Goldberg wouldn’t quarrel with me.

Yoni Yahav (narration): With the nightingale gone, in floated the dove. She flittered and fluttered to the top floor above. She read the sign and opened the door, examined the walls, the ceiling, the floor. The neighbors all gathered around to spy as the dove glanced about with the critical eye. They asked her, politely, if the rooms were alright. Perhaps she would like to stay for the night. “Are the rooms nice?” “They’re small at this price.” “Will the kitchen do?” “It’s narrow, that’s true.” “The hallway, is it roomy?” “It’s dark and gloomy.” “So you won’t stay with us?” “Yes, I will!” cooed the dove.

Maayan Yahav: Hoo-hoo!

Yoni Yahav (narration): “And in fact, I would love to live here among you. Miss Hen, I can see, is a feathery friend. This sweet cuckoo bird is true to her word. The cat’s so pristine, not a speck can be seen. The squirrel shares her treasured nuts, a generous neighbor, no ‘ifs’ and no ‘buts.’ I’m sure we’ll be able to get along, our friendly ties will remain steady and strong.” The dove decided to rent the room. Now she sits at her window and grooms her plume. In a sunlit valley, between meadow and sky, stands a fine old house that’s five storeys high. With laughter that rings from every floor, true friends…

Maayan Yahav: Hooooo.

Yoni Yahav (narration): And good neighbors. Who could ask for more?

Maayan Yahav: For more and more and more.

Yoni Yahav: Right, so what do you think of the story, Maayani?

Maayan Yahav: Nice!

Yoni Yahav: Yeah? Was the dove the good neighbor that they were looking for?

Maayan Yahav: Yes!

Yoni Yahav: Why?

Maayan Yahav: It was!

Yoni Yahav: Why was she the good neighbor?

Maayan Yahav: Because, because she loved the schneim.

Yoni Yahav: The neighbors. Yeah, she liked the neighbors.

As is the case with many other refugees, it’s hard to know where to start Christina Bazia’s story. It could – presumably – begin in 1998, when her parents fled their native Sudan in search of a safer future. It could, alternatively, begin three years later – in Beirut – where Christina herself was born. Or else it could start in June 2007, in the back of a rickety pick-up truck speeding through the Sinai Desert, with a group of frightened asylum seekers crammed together underneath a bedsheet. And just as the story has many beginnings, it has many possible end points, too: Arad, Juba, Kampala and Yehud. Marie Röder tells the haunting tale of one woman’s quest to find a place to call home.

Act TranscriptChristina Bazia: When people ask me where my home is, I find it quite hard to answer. But I… originally I come from South Sudan and that’s that’s, that’s where I know I come from, but I don’t really know where my home is.

Marie Röder (narration): That’s Christina. Christina Bazia. She’s tall, has bleached buzz-cut hair, dark skin and fierce eyes that somehow don’t seem to match the shyness of her smile. She’s nineteen years old. But listening to her you’d think she was much older. Or maybe I should say, much more mature.

Christina Bazia: I just feel I’ve been to so many places, and every time I tried to call a place my home, it was snatched away from me.

Marie Röder (narration): Christina was born a refugee. In fact, she’s what UN agencies call a “second generation refugee.” And, as is the case with many other refugees, it’s hard to know where exactly to start her story. I could go all the way back to 1998, when Christina’s parents — Jaqueline and Philipp — took their three year-old first-born daughter Viola and fled war-torn Sudan in search of a safer future. I could, alternatively, begin in Beirut, Lebanon, where the Bazias wound up, and where in 2001 — Christina herself was born. Or else, I could fast forward a few years and start in Maadi, a bustling suburb of Cairo, where Christina spent her early childhood. But instead, I’m going to open with a scene which — to Christina, too — felt like a true beginning. A modern-day exodus from Egypt. It’s June 2007, and we’re in the Sinai Peninsula. It’s a pitch-black night. Bedouin smugglers have just instructed six-year-old Christina, twelve-year old Viola, their father, their pregnant mother, and a few dozen other Sudanese asylum seekers to climb onto the back of a rickety pickup truck.

Christina Bazia: And they covered us. And they’re like, “don’t make any noise and if you do, it will be a problem to us, and to you, and so just don’t risk it.”

Marie Röder (narration): They’re speeding down bumpy desert roads that lead to the border with Israel. They’re all squeezed tightly together, covered by bed sheets, trying as best as they can to remain silent. Suddenly, the truck comes to a halt. Christina hears men shouting in Arabic.

Christina Bazia: We were like wondering what is happening? Did they find out that we are there? Because like, if the Egyptian soldiers would catch them, on the way with us, we would be dead.

Marie Röder (narration): The smugglers claim that they’re merely transporting goods, but the soldiers don’t seem to buy it. One of them pokes the sheet.

Christina Bazia: I felt someone just touching me, from outside.

Marie Röder (narration): But then, the soldiers back off. Perhaps they’ve received some bakshish, some bribe money. Maybe some other agreement was reached. Who knows?! In any event, the truck continues on. A few hours later, they stop once again. This time, the smugglers lift the bed sheets and tell the passengers to get out and start walking.

Christina Bazia: I remember crying the whole night and I was telling my dad, “I need to sleep, I have to go to school tomorrow.” And I didn’t understand actually.

Marie Roeder (narration): They approach the border by foot. Military spotlights search the terrain, trying to detect any movement. Philipp picks Christina up and dashes towards the low, barbed-wire fence which – at the time – marked the border with Israel.

Christina Bazia: It felt like only one very short wire made the whole difference that if you are the other side, you are like in danger and you could be shot and you could be killed. But if you like in the other side, you’re safe.

Marie Röder (narration): There was, of course, no parting of the sea. But much like the children of Israel, the Bazias had escaped Egypt and were now entering their new home.

Christina Bazia: Feeling so scared and then feeling so safe in the same minute. That’s how I felt.

Marie Röder (narration): And the first people they encounter? IDF soldiers.

Christina Bazia: On the other side we were like running from soldiers. When we reached Israeli land, like soldiers were coming to help us, they gave us food, they gave us blankets, they gave us like clothes.

Marie Röder (narration): Now, Christina’s story might sound familiar to you. Back then, thousands of asylum seekers were crossing the Sinai and entering Israel each year. Perhaps you recall the heated national debate sparked by their arrival. A debate in which some stressed Israel’s moral obligation to care for them, while others famously claimed that they were a cancer in the heart of the nation. Like many other Sudanese refugees who fled to Israel, the Bazias were sent to Arad, a dusty city on the edge of the Judean desert. Three months after their arrival, Jaqueline – Christina’s mom – gave birth to a baby boy. She called him Jackson. His birth marked a new, and promising, start for the family. Soon Jaqueline and Philipp found jobs at a Dead Sea hotel, while Viola and Christina enrolled in Israeli schools and underwent a rapid acculturation. Within just a few months, Christina was already fluent in Hebrew, and would rush home from school every day to watch Mexican soap operas. (Believe it or not, that’s way more Israeli than it sounds). Like many of her new friends, she joined the local chapter of the Machanot Ha’Olim youth movement.

Christina Bazia: We did a lot of things together. We danced to so many songs and we drew and we colored and I found many friends, and we became so close. There’s this one specific song that it’s just like, whenever I hear it anywhere, I just remember the times. I was like, you know, I was part of the movement, and it’s called Od Yavo Shalom Aleinu.

Marie Röder (narration): That is, “peace will come upon us.”

Christina Bazia: That alone, like, it brings a lot of memories.

Marie Röder (narration): Christina was a busy kid. Besides the youth movement, she signed up for English lessons and dance classes, spent long afternoons at the public swimming pool, or dressing up for selfie photo-shoots with her best friend Alul, herself a Sudanese refugee. Here she is, speaking to me on WhatsApp from Uganda.

Alul Gabriels: We liked… actually we loved taking pics. [laughs] Every day we would do that almost.

Marie Röder (narration): Their youth movement leader, their madricha, was Lior Lekner from Kibbutz Na’aran in the Jordan Valley. She also recalls those carefree days, nearly a decade ago.

Lior Lekner: I know Christina since she was a very young and little girl. [Laughs] A lot of energy, very smart, very sharp, knows what she want, know how to ask for it.

Marie Röder (narration): In other words, very Israeli.

Christina Bazia: At some point we felt like, you know, we’re Israeli. Like all of us speak Hebrew at home and it’s just, we, we live the same way people live here. I was thinking of like maybe I would go to the army and defend this country. I was… this is, this is my actual… this is, this is my place.

Marie Röder (narration): But just as Christina’s life in her adoptive homeland seemed more and more stable, her parents’ native country, Sudan, underwent a dramatic transition. In the summer of 2011, its southern region broke off, and gained independence.

News Reel I: At midnight tonight, Africa’s largest nation will effectively split in two.

News Reel II: Independence Day for South Sudan.

News Reel III: South Sudan’s Independence.

News Reel IV: With the excitement comes the challenge of rebuilding the country’s institutions, infrastructure and healthcare, devastated by years of conflict with the north.

Marie Röder (narration): This marked the official end of the civil war between factions of the Muslim north and the Christian south. The end, that is, of the same bloody struggle that had forced Jacqueline and Philipp to flee their country to begin with, thirteen years earlier. And as you might imagine, it was a symbolic and meaningful moment for them.

Christina Bazia: They cried. Really. Like my mom was really happy. My dad was really, really happy. And I remember like us having a celebration, because South Sudan get independence.

Marie Röder (narration): But ten-year-old Christina couldn’t really understand – or at least, couldn’t really feel – the same kind of patriotic excitement as her parents did. For her, South Sudan wasn’t home, but rather, just a far-away land. A vague concept. She had never been there, of course, nor did she know much about the circumstances that had forced her parents to leave.

Christina Bazia: It was just… it was something that was never talked about, you know, at home.

Marie Röder (narration): The impact this political development could have on her life didn’t seem tangible. Until it did. One day, at school, a teacher approached her and asked…

Christina Bazia: “When are you going back to South Sudan?” And for me, I just looked at her in a very, you know, weird way. And I was like, “what are you talking about? I’m not going to South Sudan.”

Marie Röder (narration): The Israeli government, on the other hand, thought differently. When South Sudan was formally established, Israel decided that it was no longer necessary to protect the South Sudanese population living here. In January 2012, the government announced that those who left voluntarily would receive a one-way plane ticket and $1300 US Dollars.

Christina Bazia: And my parents were among those people who left willingly.

Marie Röder (narration): But while her parents were ecstatic about returning home after so many years in exile, Christina was heartbroken. Once again, she would have to leave behind everything she knew, and start from scratch in a foreign country.

Christina Bazia: I felt like really angry, I was really fed up. I screamed and I told them that I was, I wasn’t going to South Sudan. “I don’t want to go to South Sudan. I’m staying in Israel because Israel is my home.” But my dad was like, “we don’t have a choice. We can’t stay here. And if we don’t leave, they will deport us by force. We are nothing but we are just refugees, we don’t have a choice.”

Marie Röder (narration): That was most definitely not how Christina saw herself. In her mind, she wasn’t a refugee. She was Israeli. She yelled and screamed, but to no avail. Their deportation – set for July 2, 2012 – was a done deal. But when the day came, it was nothing like the last time she left her home, hiding underneath bed sheets in the back of a truck. This time around, it was somewhat of a public event.

Christina Bazia: I felt like the whole city came to say goodbye. My teachers came, my friends from school came.

Marie Röder (narration): Lior Lekner, Christina’s youth movement leader, also came to say farewell.

Lior Lekner: We were standing like hundreds of people and escort them to the busses and giving them some medicine and some games they can take with them on the plane. We didn’t know what they will really will need and what’s going on in this new country.

Christina Bazia: There were like so many journalists, and many people asking us questions. “Are you happy?” “Are you proud to go back to South Sudan?” I just… how can I say? I swallowed all of my emotions and pretended as if I was really proud to go back and I’m happy. But deep inside, I didn’t know what I was getting into.

Marie Röder (narration): Alul, Christina’s best friend, was deported on the very same day.

Alul Gabriels: It was hard leaving our friends, having to leave everything behind, and you start a new life. We didn’t expect it.

Marie Röder (narration): I’ve seen pictures taken that day. People were crying, and hugging. And someone had made a homemade sign. “Am Israel,” it read, “Al Tishcechi Otanu.” “People of Israel, don’t forget us.” Before long, the bus with all the deportees made its way from Arad to Ben Gurion Airport. And as she boarded the plane, Christina made a promise to herself.

Christina Bazia: I was like, ‘I am going to come back to Israel. I’m going to come back.’

Marie Röder (narration): A few hours and a short layover in Ethiopia later, the Bazias landed in South Sudan. They settled down in Gudele II, a rapidly growing neighborhood on the outskirts of the new country’s capital, Juba. South Sudan was in its infancy. There was hardly any infrastructure, and people were still clearly scarred from the decades of violence and chaos. But there was a perceptible sense of euphoria in the air. The optimism of a new beginning. Far from being swept away by those sentiments, Christina focused on more mundane challenges.

Christina Bazia: There were like these small things that really made me feel uncomfortable, like the shower, the toilet, where we sleep. And it was just a whole different thing. And I just felt like it was as if falling from heaven, because at some point I had everything I wanted in Israel, but then I just had to come to this place that I don’t know how to deal with it.

Marie Röder (narration): It was a delicate situation. Christina didn’t feel like she would ever fit in in her new home. But at the same time, she could see how happy her parents were to be back. So she largely kept her discontent to herself. A year-and-a-half after they returned, the country’s honeymoon period ended. Mounting tensions between South Sudan’s two largest tribes, the Nuer and the Dinka, led to political instability and renewed violence. On December 15th, 2013, Christina was awoken by a deafening noise.

Christina Bazia: It was very early in the morning, like around three, four a.m. We heard gunshots, OK? I thought they were like, you know, thunder? I thought, like, you know, it was going to rain.

Marie Röder (narration): But one glance at her parents’ frightened faces made it clear that this was no regular storm. Meanwhile, the blasts just grew louder and louder.

Christina Bazia: It felt really close. It felt as if like it was just, you know, inside our house. And my mom she was so terrified. I saw it in her eyes, but she didn’t say nothing. My dad then left the house, he went to… he went to the market, to see what was actually happening, to hear some news, and then he came back home. And he said that a war started. I felt so terrified when he said ‘war.’ Because, I just… at that, at that point, I imagined myself dead.

Marie Röder (narration): The family barricaded themselves inside.

Christina Bazia: We were inside the room and whenever we heard the gunshots so close to us, we hid under the bed.

Marie Röder (narration): A few days later, armed men started going from house to house.

Christina Bazia: And then they ask you, “where are you from?” Like, “which tribe are you from?” And if you’re like an enemy, then they kill you.

Marie Röder (narration): What Christina is describing here are documented incidents of ethnic cleansing in and around Juba.

Christina Bazia: My dad decided that it wasn’t safe for us at home, because if we would stay for any longer, then we would be like the next people to be killed, just like how they killed our neighbors.

Marie Röder (narration): Along with friends and neighbors, the Bazias escaped to a nearby forest. But the chaos and violence followed them there, too.

Christina Bazia: This people, they did horrible things when they came there, they killed people. Many families got separated there.

Marie Röder (narration): Christina witnessed things that nobody, especially not a thirteen-year-old girl, would ever want to see.

Christina Bazia: My dad tried his best to cover our eyes and not see what’s happening, but you just cannot, you cannot just ignore all that.

Marie Röder (narration): Christina and her family were lucky — they made it out of the forest alive. They ultimately returned to their house, only to find it completely ransacked. And she could tell that that shock, that pain, was very familiar to her parents.

Christina Bazia: At that point I understood why they were actually just running from one country to another, and I understood the cause that forced them to leave Sudan. I just understood everything. Because it just looked like they were not, they were not strange to that feeling and they are not strange to that situation.

Marie Röder (narration): Christina was determined to live a different life, to write a different story, to have a different fate.

Christina Bazia: I felt I was under so much pressure that if I don’t do it now, then it’s not going to happen anymore.

Marie Röder (narration): A plan started to form in her head. She ran to the nearest open store she could find, plugged in her cell phone, and sent a Facebook message to Lior, her former youth movement leader, back in Israel.

Lior Lekner: She asked me to call her, not just write her on the Facebook. So I understand something really wrong happened.

Marie Röder (narration): Yet nothing in Lior’s life had prepared her for what she was about to hear.

Lior Lekner: I remember it was just a regular afternoon, I was in the kibbutz, walking on the path. I called her, in this moment, she told me, “you have to help me. You have to get me out of here.” I didn’t know from where she had the power to say it after all she’d been through and saw, but it was like her survival way of looking for every person who can help. I was very shocked in the beginning and very frightened. ‘What can I do?’ ‘How can I help her?’ She is depending on me. She needs my help. And she… she… she turned to me.

Marie Röder (narration): As soon as they hung up, Lior sprung into action. She got in touch with “Come True” — an Israeli organization Christina had mentioned on the phone. Their mission was to take children from South Sudan to neighboring Uganda. Lior asked what needed to be done in order to bring Christina to safety. And the answer was surprisingly simple.

Lior Lekner: All we needed was money because the way was… was open.

Marie Röder (narration): Lior set up a crowdfunding campaign and asked her friends to donate. Within just a few days, she managed to raise $1200 dollars — enough to pay not only for the transfer of both Christina and her sister Viola to Kampala, but also for school fees once they got there.

Christina Bazia: I felt really good and happy that I was going out of South Sudan. But on the other hand, I felt horrible that I was leaving my parents behind and didn’t know what was actually going to happen to them.

Marie Röder (narration): In early February 2014, Philipp escorted his two daughters to the central bus station in Juba.

Christina Bazia: My dad was like, “take care of yourself. Don’t be a very stubborn kid, listen to your sister. And don’t think about us. We’re going to… Whatever is going to happen, just, you know, just know that we love you, we’re very proud of you.” And yeah, that’s… that was his last words before we left.

Marie Röder (narration): Kampala was a thirteen-hour bus ride away. But for the Bazia sisters, it might as well have been a different universe. A safe one, yes. But also a foreign and lonely one.

Christina Bazia: Uganda, it was like, you know, it was another different world. I was used to the fact that my parents directed me and told me what to do and did everything for me. And, you know, were there always for me. And, it was, you know, it was hard. And I… I became… I just, you know, I became an adult at a very young age. I became my own parents.

Marie Röder (narration): The sisters were soon separated, each sent to a different school. Christina barely made any friends.

Christina Bazia: I just… I didn’t feel comfortable turning to anyone if like I had problems or I felt bad.

Marie Röder (narration): Till one day, out of the blue, a parcel addressed to Christina arrived at the school. It was from Israel, and had some pencils, notebooks and sweets. And there was also a letter, signed by a woman called Shira.

Shira Ami: OK, my name is Shira. Shira Ami. Married to Eli. I’m sixty-eight.

Marie Röder (narration): Shira lives in Yehud. She’s petite, and energetic, and her friendly face has deep laughter lines. A few weeks earlier, she had come across a Facebook post by “Come True” — the organization that had brought Christina to Uganda — and had decided to become a sponsor. Christina’s sponsor.

Shira Ami: And since I am a very talkative, verbal person, I asked Christina if she wants to correspond with me. And since Christina is a very talkative and verbal person, she said “yes.”

Marie Röder (narration): They began exchanging messages.

Shira Ami: And she shared with me some of her experiences. And I reacted. And from time to time I gave her an advice.

Eli Ami: It started being more and more personal.

Marie Röder (narration): That’s Eli, Shira’s husband.

Eli Ami: Christina understood that this is an opportunity for her to ask for help, for advice. It became much more than just sending a check once a month, and her thanking us.

Marie Röder (narration): In ways Shira couldn’t have imagined, she was exactly what Christina needed: someone to lean on. And even more so, she represented an unexpected link back to Christina’s childhood home, Israel. They’d talk about Christina’s experiences at school, about her parents back in South Sudan. Shira would send pictures of her daughter and two grandchildren.

Christina Bazia: And one day, she heard about this school called Givat Haviva.

Marie Röder (narration): Givat Haviva is a boarding school, not far from Hadera, that accepts international students. And once she heard of it, Shira immediately thought…

Shira Ami: Hey! I want this for Christina as well!

Christina Bazia: And then she told me about it. And I’m like, “of course!” I was like, “of course I am in, I want, I want to go there and I really want to study there.”

Shira Ami: But first of all I asked Eli, “Eli, what do you think? Can we bring Christina to Israel? We’ll ask for a help of our family, of our friends.” And he said, “OK, that’s a good idea.”

Eli Ami: I learned one thing in life and that is that following Shira and her crazy ideas is always interesting. So I follow her.

Marie Röder (narration): Now, if you’re like me, perhaps you’re surprised by the apparent ease and lightheartedness with which Shira and Eli made this move. I mean after all, here they were, a retired couple in their late sixties, deciding to take in a Sudanese teenager who — text messages aside — was basically a complete stranger. I asked Shira about their motivation, and fittingly, she moved straight into Hebrew.

Shira Ami: As far as I’m concerned, this is Zionism. For me, this is acting as an Israeli. Taking care of the society I live in. That’s my motivation. That’s the explanation for why I’m doing this. And yeah, some people will say, “OK, fair enough, you want to help? Help the people who are already here in Israel. But why on earth would you bring back somebody who’s already left Israel and lives somewhere else?” I don’t know. Maybe because I feel like I owe this person something, because they were deported from here? Maybe because I feel like I still have a debt to pay? In any case, why does it matter? A human is a human is a human.

Marie Röder (narration): And it was that unadorned belief that guided Shira and Eli throughout the long and complicated bureaucratic process of getting Christina to Israel. As they filled out countless forms and applied for permits and visas, they maintained an unwavering conviction that they were simply doing the right thing. Finally, they got the green light. Christina could come to Israel. In just seventeen years, Christina had been through more trauma than most people experience in a lifetime. She’d been smuggled and deported, she’d witnessed war and violence, and she’d been separated from her parents at the age of thirteen. But here she was, returning to the country that had once expelled her. A country that she nevertheless still viewed with rose-colored glasses. When she landed at Ben Gurion Airport in September 2018, Christina was elated. She was finally fulfilling the promise she had made to herself at the very same place six years earlier. She had returned to Israel.

Christina Bazia: When I landed, I just, you know… I’m like, wow, I am in Israel and, I said I was going to come back, but I didn’t know how, but I’m in Israel. And I felt so excited. And then we came out and we saw like bunch of people waiting for us, like, you know, many people waiting.

Marie Röder (narration): Among them were Lior and other old friends from Arad.

Christina Bazia: And I saw many people like you know just there to welcome us, to welcome me. And I felt so, so loved.

Marie Röder (narration): Shira and Eli were there, too.

Shira Ami: I went up to her, I hugged her, and I told her “we’ll be your family in Israel.” And that was a promise, a promise from which we didn’t shift even an inch.

Marie Röder (narration): It was, therefore, a sweet homecoming. An optimistic one. But given all that had happened since she had last left the country, could Israel still be her home? Two-and-a-half years later, that’s a question Christina is still trying to answer. See, just as her story has several possible starting points, it could end in different places, too. I could stop right here, at Ben Gurion Airport, with Christina triumphantly returning to her childhood home. Or else I could go on a bit farther, and mention how last spring, Christina got her high school diploma from Giv’at Haviva. If we’re really in the mood for a feel-good ending, I could say that earlier this year, she began university, and now lives in the dorms on campus. I’d tell you that she visits Shira and Eli on weekends, and that she has long phone calls with her parents and siblings. All those endings would, of course, be true. But they are not the ending I chose to tell you. I’ve spent a lot of time with Christina over the last few months. We’ve had long chats, and without us even realizing it, almost all of them end up being about one question: “Where is home?” I’ve struggled to figure out where her story ends. And ultimately, I settled on an ending which isn’t quite so neat or tidy. See, Christina’s entire journey — the many places she’s called home — have each left their mark on her. They’ve made her worldly, for sure, but they’ve also made her sober. In the years since her return to Israel, she’s encountered incredible generosity and warmth. But she’s also seen less rosy sides of the country: Racism, intolerance, xenophobia. And those experiences have complicated her fuzzy childhood memories of Arad.

Christina Bazia: As much as I felt I was home, I was not actually at home. Because I was not like any other citizen in Israel. And that alone, excludes me from the society. There are so many good people. There are so many nice people. But there are also some people who don’t really understand what we, as black people, go through, what we have to experience each and every day. You know, people are forgetting that we are all humans. It’s so complicated to think of home, when all what I went through is just not the definition of home. But I think also home can be, can be, can be people. I feel home now, because I’m with the people I love and who care for me and who showed me that they will be there for me no matter what. So when I define home, I can mention peoples’ names instead of countries.

Zev Levi scored and sound-designed the episode with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Tal Blecharovitz composed the original music for Room for Rent. Sela Waisblum created the mix. Thanks to our dubbers, David Satran and Karni Arkin, and to Lea Millel-Forshtat, Douglas H. Johnson, Nan Galuak, Thomas Kon, Federica Sasso, Rotem Ariav, Sheila Lambert, Erica Frederick, Jeff Feig and Joy Levitt.

The end song, Slichot, was written by Leah Goldberg, arranged by Oded Lerer and performed by Yehudit Ravitz.