Mordechai Schattner was born in Eastern Galicia – then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – in 1904. He was a student activist in Zionist movements such as the socialist Young Guard, or HaShomer HaTzair, and HeChalutz, The Pioneer. He made aliyah in 1925, and helped establish Kibbutz Ein Harod, in the Jezreel Valley.

It was there that he became a Labor Party mover-and-shaker, and was ultimately dispatched to pre-war Europe, where he had dealings with the heads of the Nazi regime, including Adolf Eichmann.

After returning to Mandate Palestine, he was elected to the Va’ad HaLeumi, the Jewish National Council, and worked primarily on matters of national infrastructure.

After signing the Declaration of Independence, he served in a series of financial posts – as a representative of the Department of Treasury in Jerusalem, as the head of governmental real estate and infrastructure development agencies, and as the man in charge of the Unit for Unclaimed Property. He was also one of the six founders of Yad Vashem, the National Holocaust Museum, the driving force behind the creation of the town of Nazareth Illit in the Galilee and the Wingate Sports Center, and a member of the committee that selected Israel’s first Supreme Court justices.

He died in 1964, at the age of sixty.

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: There were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

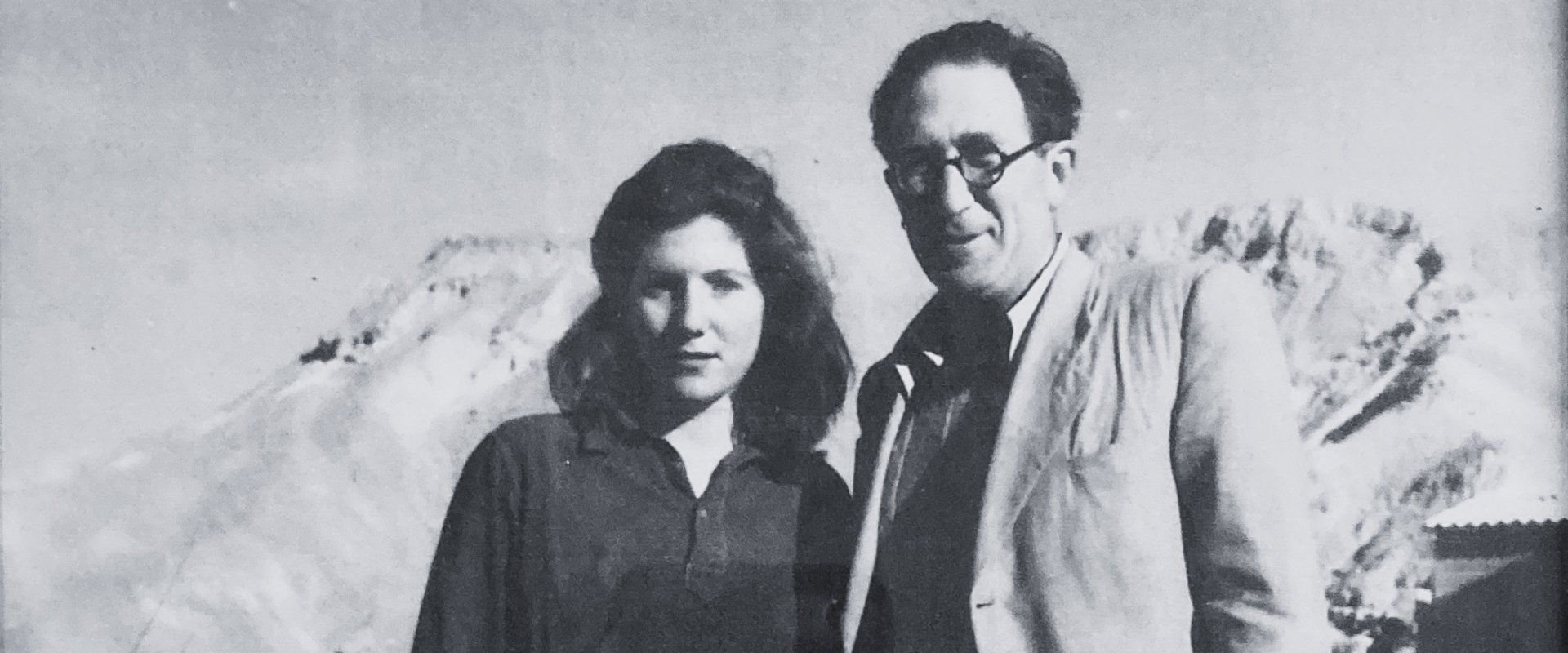

Today we’ll meet Mordechai Schattner, and his daughter, Rachel Ofra Eliyahu Schattner. She’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Act TranscriptRachel Ofra Eliyahu Schattner: In 1946, we had the Black Saturday. British soldiers decided that they will find all the artillery in the kibbutzim. And they decided to come at night with machine guns and cars and everything and try to look for it. But every kibbutz made it disappear. In Ein Harod, everyone was sitting in front of the dining room, sitting and singing and so on. And the cars of the British came slowly slowly from the road. My father saw them coming. So he went down to the cooks. And he said, “please do a big big pot of tea, immediately! Put it now immediately.” And he went to the commander, and he said, “timeout, timeout, listen, tea time. You have from the morning, you didn’t drink anything, we’ll get you a tea.” And they got tea. And they were quiet. And they didn’t find anything.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Rachel Ofra Eliyahu Schattner, the daughter of Mordechai Schattner, who – despite the cup of tea – was taken to prison on that fateful Shabbat – June 29th, 1946.

Newsreel: Two-hundred thousand Jews are being checked by two divisions of British troops and Palestine Police. Twenty-five thousand people are being interrogated each day. Our troops, in sternly guarded surroundings, are looking for members of the notorious Irgun Tzvaii Leumi, and the Stern Gang, suspected of blowing up the King David Hotel in Jerusalem.

Mishy Harman (narration): Operation Agatha, or as it was known among the Jewish population – Shabbat Ha’Shchora, or The Black Sabbath – saw the round-up of nearly three thousand local Jewish leaders and marked a tipping point in the relations between the mainstream organizations of the Yishuv and the British military forces in Palestine. For Schattner himself, it was the start of over four months in prison at the British detention facilities in Atleet, Rafah and Latrun, where he served time with future Prime Minister Moshe Sharett as well as many other important Zionist leaders.

[Signed, Sealed, Delivered? introduction]

Mishy Harman (narration): Here’s our producer Lev Cohen, with Rachel Ofra Eliyahu Schattner, Mordechai Schatner’s eldest living daughter.

Lev Cohen (narration): Mordechai Schattner was born in Eastern Galicia – then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – in 1904. He was a student activist in Zionist movements such as the socialist Young Guard, or HaShomer HaTzair, and HeChalutz, The Pioneer. He made aliyah in 1925, and helped establish Kibbutz Ein Harod, in the Jezreel Valley.

It was there that he became a Labor Party mover-and-shaker, and was ultimately dispatched to pre-war Europe, where he had dealings with the heads of the Nazi regime, including Adolf Eichmann.

After returning to Mandate Palestine, he was elected to the Va’ad HaLeumi, the Jewish National Council, and worked primarily on matters of national infrastructure.

After signing the Declaration of Independence, he served in a series of financial posts – as a representative of the Department of Treasury in Jerusalem, as the head of governmental real estate and infrastructure development agencies, and as the man in charge of the Unit for Unclaimed Property – which essentially meant dealing with homes of Arabs who left/fled/were forced to flee (pick your preferred terminology), in 1948. For almost a decade he led a branch of the Finance Ministry called (this was a welfare state after all…), the Department of Frugality. He was also one of the six founders of Yad Vashem, the National Holocaust Museum, the driving force behind the creation of the town of Nazareth Illit in the Galilee and the Wingate Sports Center, and a member of the committee that selected Israel’s first Supreme Court justices.

More than anything, he was a voice of reason. While maintaining his unwavering commitment to socialist ideologies, Schattner was a calm and moderate man, who tried to find commonalities and compromises wherever possible. That appeasing attitude didn’t succeed in his own backyard, however, and following the 1952 ideological split at Ein Harod – a split between Stalinists and more Western-aligned socialists – he opted to leave the community he loved and built. That rupture continued to pain him for the rest of his days, up until his death in 1964, at the age of sixty.

Here he is recalling the tense early days of the State.

Mordechai Schattner: The tension was very high and we stood at the precipice of civil war. Among the members of the National Council, I was always one of those who looked for a way to avoid a forceful clash. Because I thought then, and I still think I was right, that we could not have withstood wars against the Arabs and the British and a civil war among the Jews. If that would have happened, I thought we’d surely be lost.

Rachel Ofrah Eliyahu Schattner: My name is Rachel Ofrah Eliyahu Schattner. I live in Ramat Chen, a part of Ramat Gan. The name of my father was Mordecai Schattner, my mother called him Marduak. They met each other in Holland, in a place that they learned agriculture. He came to Israel and went back and came again. And the second time that he came, he came to Ein Harod in the late ’20s. Why Ein Harod? In Ein Harod the idea from the beginning was to make a kibbutz that will be as big as possible. If someone wants to come, he will become a member. There was a whole lot of people that came, worked a little bit, and they saw that it’s not for them. A lot of people. Ein Harod started with a spring and with a lot of swamps and a lot of malaria. A lot, a lot. Many, many of them died from malaria, and many suicide, and many children died there also. And that was the beginning of Ein Harod. Even sweets we didn’t have, even sweets! Imagine children grow up without sweets? Impossible. They did a little bit sugar with water. And we had a lot of songs about grapefruit. [Rachel sings]. Maktefa is those scissors. [Rachel sings]. How they pick it, wrap it and they put it in a box. [Rachel sings]. And King of England will eat it. [Rachel sings]. My father he was asked to go to Germany after Hitler was elected. They felt that it’s time to go and to bring Jews over here. So they took my sister and went to Berlin. They left me in Ein Harod with a friend of my mother. I was six months. Afterwards they came back. He was asked to go back just before the war, just before the war, ’39. But to London. In the Blitz time! We lived in Finchley. I don’t remember him being worried. My father had to dig a place in the garden and someone brought sacks with sand and some cover and we went to… we slept there, but there was no harm. Sleep here, sleep there, [in Hebrew] it was OK. He collected a lot of children. And he had to send them out of England. Years afterwards, my brother was hitchhiking here in Israel. So when he said that he’s from Ein Harod, “ah, Ein Harod? Schattner?! [In Hebrew] Do you know that he saved me? He saved me!” But he couldn’t convince his family. He went few times. They were in Kyiv and in Warsaw. And they said to him, “we are the bourgeois, nothing will happen to us. It’s impossible that anyone will want to harm us.” He had this sister and a brother that was saved. That’s all, all the rest were… with children with grandchildren, all of them. I remember my mother told us that when he heard that his mother died in Poland, he cried. I never saw him crying. Never. It was the general spirit, by all of us, in Ein Harod. And if something has to be done, has to be done. Ben-Gurion declared the State. We were all listening. It was a joy. Really. I never saw it before, I never saw it afterwards. It’s God’s work. It’s talking about the heart of a liberal, democratic Jew in Israel. Every time I read it, I think you don’t need every [in Hebrew] constitution, laws, other matters, because it’s all here. I know it by heart. My father was so emotional about the Declaration of Independence. He wrote very big. He said, “I’m writing it big so it will be for you easy to recognize.” When we are going to somewhere and we see all the signatures, our children knows already. Ah! [in Hebrew] Here’s grandpa! Here’s grandpa! My parents went out of Ein Harod because there was a big ideological crisis. They went to Jerusalem. I can’t understand why he decided to leave. It was really wrong decision. They had nothing. After 26 years in Ein Harod, nothing. Afterwards, he was in charge of all the property of the people who left Jerusalem. He could have arranged for my sister and for myself houses [in Hebrew] just like that, without… But he never did it. Never, never, never. We were born and raised and lived up till now by people with values of freedom, of thinking, of feeling, of relationship. It was a self-understanding that the most important thing in life is Israel, not us. Israel. No more. I don’t see it. No more. We have to agree and acknowledge the fact that we are conquering another nation. It’s impossible. If we don’t want anyone to be our boss, why are we boss of someone else? It’s so wrong. The way of thinking is not good, not good at all. I feel strongly that we are dealing in lies, we are dealing in lies! It gives me to vomit. It’s hypocrisy. My daughter Gali, she’s saying, “I’m going away. And you are invited.” She’s “I’m going, I’m taking my two children. I’m going away.” And I said, “I’m not going. I’m not going.” It goes without saying, Israel is a part of me and I will not leave it until I will go to heaven.

In 1961 Eliezer Whartman of the Israel State Archives conducted a series of interviews with 31 of the 37 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. For the full interview with Mordechai Schattner, see here.

Like many of the well-established kibbutzim, Ein Harod Ichud has a rich archive. See this website (in Hebrew) for information about the history and culture of the kibbutz, including links to Ein Harod specific songs, as well as a book celebrating the kibbutz’ centennial.

For a similar site for the “sister” kibbutz, Ein Harod Meuchad, see this website (in Hebrew) which includes many videos.

The Mishkan Museum of Art Ein Harod – which was recently selected by Haaretz as one of the 13 most beautiful buildings in Israel – was founded, in a wood hut, in January 1938, and is today home to many important and groundbreaking exhibits.

For a learned audio discussion on the ideological rupture within the kibbutz movement, see Itzhak Noy’s radio program.

For background on the events leading up to the ‘Black Sabbath,’ see the Central Zionist Archives’ website (English), and for Operation Agatha see the Palmach website (Hebrew).

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubber is Yoav Yefet.

The end song is Po Ein Harod (lyrics – Aharon Zeev Ben-Yishai, music – Yariv Ezrachi, arrangement – Zahi Fodor), performed by Dudu Elharar.

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.