Meir Argov was born as Meir Grabovsky in Rîbnița, Bessarabia, in 1905. At the age of 14, while his family was fleeing civil unrest in the region, his father Yeshayahu – a learned man and a grain salesman – was murdered on the road to Oleksandriia. His remains, in what Argov once called “the land of blood,” were only recovered several months later.

Argov himself attended a cheider, a gymnasium and the University of Kiev. As a prominent young leader in both the Halutz and the Tze’irei Zion youth movements, he was repeatedly arrested by the Russian secret police and was ultimately deported to Mandatory Palestine in December 1924 – a reprieve of sorts, as the much more common option was being exiled to Siberia.

Here in the Land of Israel, he worked in the orange groves of Ness Ziona and Petach Tikvah and later became a fiery labor leader, as the secretary of the Petach Tikvah Council of Workers. He was active in Ben-Gurion’s Labor Party, Mapai, and even served on the Petach Tikvah Municipal Council as their representative.

Though he was already married and a father to twelve-year-old Tamar, in 1941 he volunteered for service in the Palestine Regiment of the British Army. At first, the mostly Jewish enlistees of the 14th infantry company spent their days marching around local parade grounds and guarding warehouses, adhering, he later wrote, to a routine riddled with “suffering, boredom, indifference and despair.”

Only in November 1944, as part of the newly-founded Jewish Brigade, was he finally deployed, reaching Italy and inching towards the actual front. In an essay called “Lit Candles in the Jewish Sector,” he described his first glimpse of German soldiers. They were POWs dressed in rags, being rowed out of the harbor of Taranto. But their sorry state didn’t fool him. Argov wondered whether among them are “those who crushed the skulls of Jews, and showed their valor by slaughtering women and children.” He and his fellow Jewish comrades did nothing, he recalled, but “seal in their hearts a breath of fury.”

Over the course of the next few months the brigade was, at last, thrown into combat. In April 1945 they fought their way across the Senio River – helping win one of the last battles of the war in Italy. The Jewish Brigade, which consisted of some 5,000 soldiers, lost 57 men.

After the war, he helped organize illegal Jewish immigration to Palestine, and – as a member of the National Council – prepared the local postal service for independence. Since neither the name of the state-to-be, nor the name of its currency, had been determined, designing its inaugural stamps could have been a difficult task. But nothing, not even the lack of a name, was going to stop Argov, David Remez and their fellow Zionist leaders. It was soon decided that the first stamps would bear the heading of Do’ar Ivri or Hebrew Post, and wouldn’t depict illustrations of landmarks or landscapes (since – after all – no one knew what the borders of the new State would ultimately be, and which regions would, or wouldn’t, end up being part of the country). Instead, the stamps (which were designed by Otte Wallish – who, incidentally, also designed the scroll of the Declaration of Independence) featured images of ancient Jewish coins from the first and second revolts against the Romans. Issued hastily and under suboptimal conditions, some prints contained spelling mistakes and discolorations. Nevertheless, on the whole, the mission was a success and the stamps were officially released on Sunday, May 16, 1948 – the country’s very first day of business. Today, unsurprisingly, full sets of the original nine Do’ar Ivri stamps sell for hundreds of thousands of Shekels.

Argov – who was both a lifelong Mapai Party member and a traditional Jew who often led services in Ness Ziona on the holidays – called the day of the Declaration of Independence a “Genesis moment.”

He was elected to the first Knesset and appointed Chairman of the powerful Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee – a role he held till his sudden death, of a heart attack, in 1963.

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: there were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

Today we’ll meet Meir Argov, and his daughter, Tamar Argov de Groot. She’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Act TranscriptTamar de Groot: How my father was in politics or as usual? But politics and my father was the same. He was not interested in any other things.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Tamar Argov de Groot, the daughter of Meir Argov, a World War II veteran and a Petach Tikvah-based labor organizer who loved chazanut, or cantorial music, and was Israel’s first – and longest serving – chairman of the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee.

[Signed, Sealed, Delivered? introduction]

Today we’ll meet Meir Argov, and his daughter, Tamar Argov de Groot. She’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Here’s Italian journalist Federica Sasso with Tamar Argov de Groot, Meir Argov’s daughter.

Federica Sasso (narration): Meir Argov was born as Meir Grabovsky in Rîbnița, Bessarabia, in 1905. At the age of 14, while his family was fleeing civil unrest in the region, his father Yeshayahu – a learned man and a grain salesman – was murdered on the road to Oleksandriia. His remains, in what Argov once called “the land of blood,” were only recovered several months later.

Argov himself attended a cheider, a gymnasium and the University of Kiev. As a prominent young leader in both the Halutz and the Tze’irei Zion youth movements, he was repeatedly arrested by the Russian secret police and was ultimately deported to Mandatory Palestine in December 1924 – a reprieve of sorts, as the much more common option was being exiled to Siberia.

Here in the Land of Israel, he worked in the orange groves of Ness Ziona and Petach Tikvah and later became a fiery labor leader, as the secretary of the Petach Tikvah Council of Workers. He was active in Ben-Gurion’s Labor Party, Mapai, and even served on the Petach Tikvah Municipal Council as their representative.

Though he was already married and a father to twelve-year-old Tamar, in 1941 he volunteered for service in the Palestine Regiment of the British Army. At first, the mostly Jewish enlistees of the 14th infantry company spent their days marching around local parade grounds and guarding warehouses, adhering, he later wrote, to a routine riddled with, quote, “suffering, boredom, indifference and despair.”

Only in November 1944, as part of the newly-founded Jewish Brigade, was he finally deployed, reaching Italy and inching towards the actual front. In an essay called “Lit Candles in the Jewish Sector,” he described his first glimpse of German soldiers. They were POWs dressed in rags, being rowed out of the harbor of Taranto. But their sorry state didn’t fool him. Argov wondered whether “among them,” quote, “are those who crushed the skulls of Jews, and showed their valor by slaughtering women and children.” He and his fellow Jewish comrades did nothing, he recalled, but “seal in their hearts a breath of fury.”

Over the course of the next few months the brigade was, at last, thrown into combat. In April 1945 they fought their way across the Senio River – helping win one of the last battles of the war in Italy. The Jewish Brigade, which consisted of some 5,000 soldiers, lost 57 men.

During a short break from the action, Argov found time to visit the tomb of Dante Alighieri in Ravenna, writing in his journal that the great Medieval poet could never have dreamt that our generation would be put through a hell so awful it would far surpass the “daring imagination of the envisioner of purgatory” himself.

After the war, he helped organize illegal Jewish immigration to Palestine, and – as a member of the National Council – prepared the local postal service for independence. Since neither the name of the state-to-be, nor the name of its currency, had been determined, designing its inaugural stamps could have been a difficult task. But nothing, not even the lack of a name, was going to stop Argov, David Remez and their fellow Zionist leaders. It was soon decided that the first stamps would bear the heading of Do’ar Ivri or Hebrew Post, and wouldn’t depict illustrations of landmarks or landscapes (since – after all – no one knew what the borders of the new State would ultimately be, and which regions would, or wouldn’t, end up being part of the country). Instead, the stamps (which were designed by Otte Wallish – who, incidentally, also designed the scroll of the Declaration of Independence) featured images of ancient Jewish coins from the first and second revolts against the Romans. Issued hastily and under suboptimal conditions, some prints contained spelling mistakes and discolorations. Nevertheless, on the whole, the mission was a success and the stamps were officially released on Sunday, May 16, 1948 – the country’s very first day of business. Today, unsurprisingly, full sets of the original nine Do’ar Ivri stamps sell for hundreds of thousands of Shekels.

Argov – who was both a lifelong Mapai Party member and a traditional Jew who often led services in Ness Ziona on the holidays – called the day of the Declaration of Independence a “Genesis moment.”

He was elected to the first Knesset and appointed Chairman of the powerful Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee – a role he held till his sudden death, of a heart attack, in 1963.

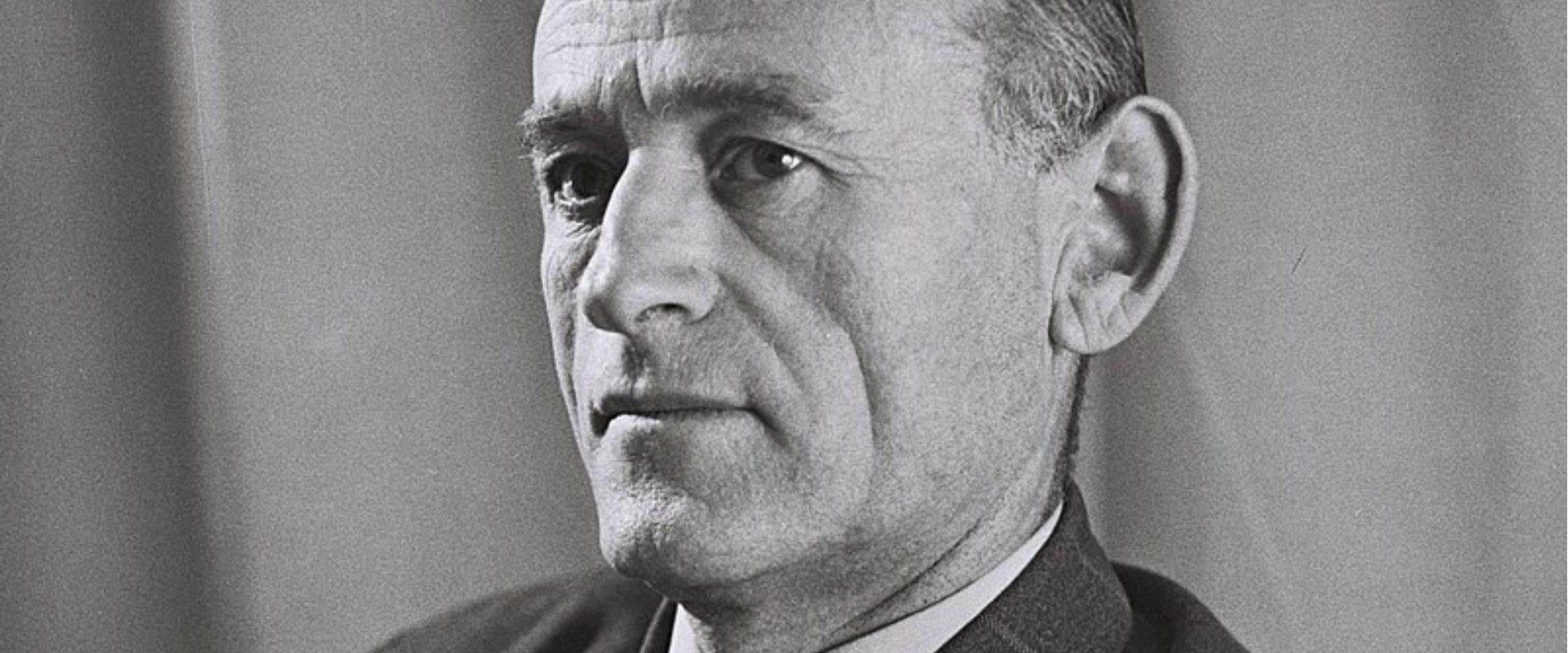

Here he is, in 1961, discussing the tenuous nature of the nascent country.

Meir Argov: A country can be lost. There was a first temple, a second temple, and now, OK, there is a third one. To suppose that a fourth temple will be founded if the third one is destroyed, that is something I cannot do. It seems to me that if it is destroyed, it’s unlikely there’ll be a fourth one.

Tamar de Groot: I’m Tamar de Groot. I was born in Tel Aviv. I’m the daughter of Meir Argov. I’m the only child, and my parents also were here alone because they were expelled from Russia as youngsters. Both of them had no family here in Israel. They lived very very poor but he was proud of it. His first name was Grabovsky, and all the time he did not want to change it, because he said, “what will be if someone after the war” – because he lost all his family – “so maybe some of my relatives will come to this place and he ask for Grabovsky and no one will know it because I’ll be Argov,” because Ben-Gurion said to my father, “you have to be Hebrew name!” The relationship between them was equal and we live not far from each other. Ben-Gurion used to write on every book that belongs to him, he wrote his name so everybody has to know that it belongs to him. And he had a lot of books of the Mein Kampf. And because it belongs to him, it’s written “Ben-Gurion” on the book. We were neighbors and Ben-Gurion has a lot of books so my father used to come to him to see the books and so on, and he gave him, as a gift, Mein Kampf with the sign of Ben-Gurion. My grandson found it and he said, “what! Mein Kampf with Ben Gurion?!” You see, the Haganah send him at the beginning to the British army to be a soldier. When he was in the British army, I knew that if I’ll write him just a regular letter, you know, as a child writing to her father, “yeah, OK.” It’s not interesting for him. So I was reading the newspaper before I was writing him a letter. And then I wrote him what’s going on in the country and so on and he was so proud of me. After that I met people that were with him in the same tent. And they said every time that he got a letter from me and I was telling him what’s going on in the politics and so on and they all remember. I met someone long after he died, and he said, “you know I was with him in the army and he was so proud to read your letters.” Because I knew that if I’m writing, “yeah I’m going to school and do…” it will not interesting him at all! He was in politics. That was all his life. He even did not know how old I am. I… I know that once when he came back from the army and I came late home, and he said, “what? She should not come so late.” And my mother said, “she’s 16 years old!” He thought that I’m a small child. At the beginning of the foundation of Israel, I knew everyone. Personally. I’m old enough to know them. I’m smiling that he’s signing the Israeli Declaration! Now you feel it. Then you thought it’s natural because he was in the group of the leaders, so he should sign. But now we understand that it is unique. In the War of Independence I was in the Palmach. I fought in the way to Jerusalem, in Shoresh was our base. He was in the Va’ad Haleumi, the Jewish National Council, and he went to Jerusalem then and he met me and he was very proud. After the war I went back to school for another year and then I became a teacher here in Jerusalem. I was a teacher all my life. He was in politics. That was his life and this was his thinking. In those times I was very interested and very proud what’s going on. Now the politics is less interesting me. People that are in the high places are not reliable at all. I don’t believe them. I’m very sorry what’s going on. My father died very early, he was 60 years old. Oh, he will not believe what… what’s going on here in politics. Politics have so changed from those time. The Declaration was after the regime of the British. People were thinking more about country than about themselves. And if he was here he would’ve very very sorry about this. He will be ashamed. I’m sorry that I fought for a country that is not what he wanted to be. And I also don’t believe in. I wish for Israel to be more clean from cheating. You see, I fought for Israel. We fought here very hard! I was born here. It’s my country. We lived in America, but I didn’t like America at all. I was too Israeli. He thought that everyone that can live here should live here. That was his dream of his life. Do I want my children will live here? Ho and how! I’m sorry that one child is living in Holland. He went to the country of his father. But my father will be proud that Israel is Israel! With the fault, with the things that it did not think about. We have our own country! It’s the biggest achievement of the Jews in the world.

Mishy Harman (narration): We interviewed Tamar Argov de Groot last December in her home in Jerusalem. Five weeks later, on January 31, 2023, she passed away at the age of 93. This, it turned out, was her final interview.

In 1961 Eliezer Whartman of the Israel State Archives conducted a series of interviews with 31 of the 37 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. For the full interview with Meir Argov, see here and here.

For an account of Argov’s life, through a series of biographical sketches and expository essays, see Meir Argov’s 1971 book, Ma’avakim (Hebrew).

For background on the cultivation of oranges in Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine, as well as the public campaigns to include Jewish laborers in the work in the fields and orchards, see Ness Ziona: A City with the Heart of an Agricultural Colony (Hebrew) and this excerpt, from the 1913 film The Life of Jews, about the orange orchards of Petach Tikvah. By the way, the Hebrew word for orange – tapuz – is an acronym of golden apple (tapuach zahav), and was taken from Proverbs 25:11 (“A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in a setting of silver”). Most scholars agree that the reference in that biblical verse was to ornamental apples made of gold inlaid in silver. In the early days of the Yishuv, the local orange – which was at the center of Argov’s organized labor campaign – came to symbolize Israeli agricultural industriousness.

For background on the formation and actions of the Jewish Brigade during World War II, see – among countless books, articles and studies – this short write-up on the Yad Vashem website. For a more personal account of the “life and times” of the Jewish Brigade, see this article by Rami Litani, the son of brigade sergeant-major Eliyahu Litani.

Finally, for background on Israel’s first Do’ar Ivri postage stamps, see this 1958 article from the Davar daily (Hebrew), and this English-language write-up from the Society of Israel Philatelists.

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubber is Leon Feldman.

The end song is Kol HaDrachim Movilot LeRoma (lyrics – Itzhak Itzhak (Itzhak Ben-Israel), music – Zvi Ben-Yosef, arrangement – Mordechai Shelef), performed by Havurat Shoham and Giora Ross.

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.