More often than not, we think of Jewish-Arab relations in Israel as being adversarial. We frequently hear tales of hatred, violence, animosity and discrimination. But reality is, of course, much more complicated: Not only are some Jews actually Arabs, and vice-versa, but there is a tremendous amount of intermingling, sharing and cooperation. In this episode, we explore some of these fascinating points of contact.

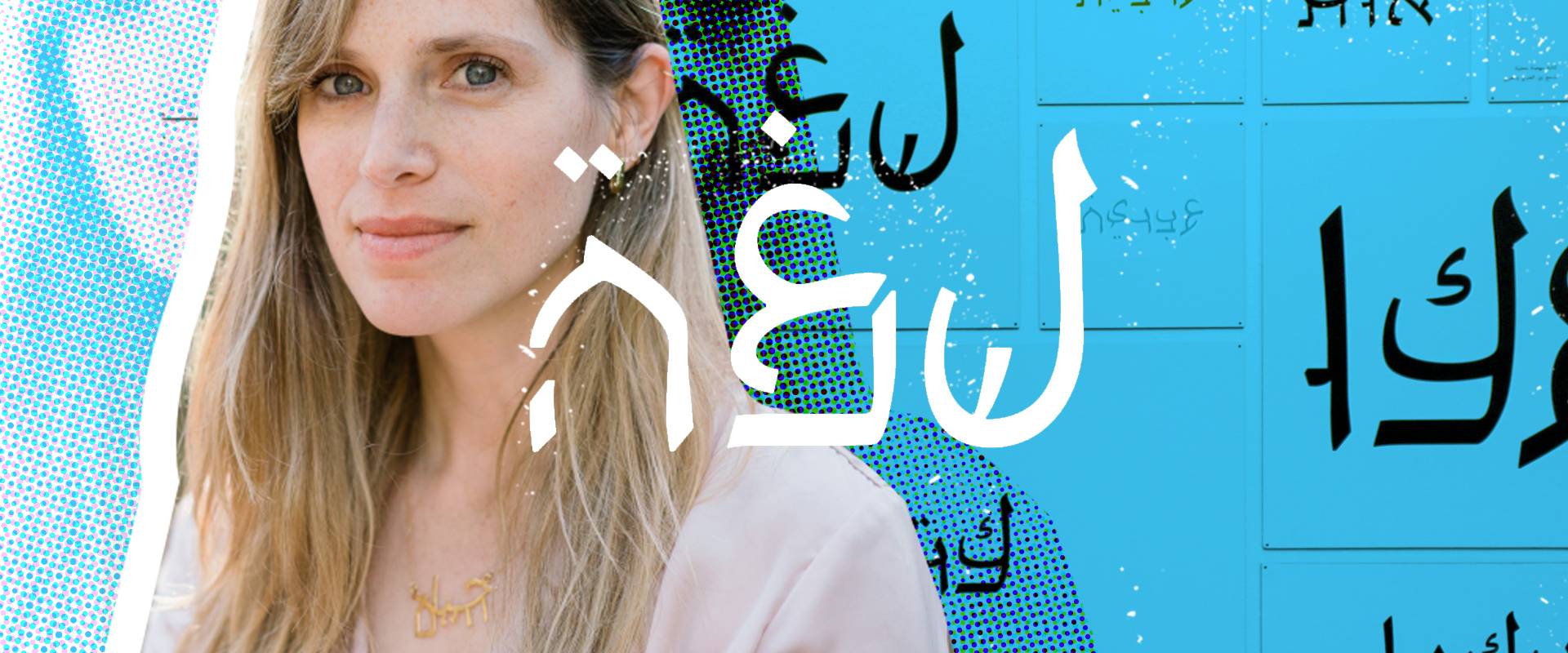

Host Mishy Harman talks to Liron Lavi Turkenich, a type and graphic designer from Haifa, who invented a hybrid Hebrew-Arabic script.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): I met up with Liron Lavi Turkenich in Haifa.

Liron Lavi Turkenich: We’re in Haifa, my hometown, and we’re sitting in a nice room [Liron laughs]. A nice quiet room and discussing type and letters.

Mishy Harman (narration): Liron, you see, is a typeface designer.

Liron Lavi Turkenich: I always loved languages and words, and letters and books [Liron giggles]. Actually, I didn’t know why I want to be a graphic designer, and then I realized that there is sub-profession in this profession that is called typeface design. And when I knew that you can design letters, and someone actually designs letters and how they look, this is the moment I fell in love and I knew I wanted to do that for my career.

Mishy Harman (narration): And Haifa, where Liron grew up, turned out to be the perfect setting for launching that dream career of hers. So, two quick things you need to know. One: Any official signage in Israel – road signs, signs on governmental buildings, things like that – should, at least according to the law, be written in Hebrew, Arabic and English. And two: Haifa has a pretty sizable Arab minority, something like ten percent of the population. But Liron never studied Arabic, and couldn’t read the Arabic on any of the countless multilingual signs around town.

Liron Lavi Turkenich: And at some point I realized that I’m looking at the Arabic as if it’s decorations and not like it’s letters with content. And it really started to bother me. How is it possible that for thirty years I’ve been staring at these signs and not really noticing that Arabic has something to say? And I wanted to start a project that will give the Hebrew and the Arabic the same kind of respect.

Mishy Harman (narration): At the time she was an undergrad at the Shenkar College of Engineering, Design and Art. She was about to graduate, and was searching for an idea for her final project. That’s when she stumbled upon the work of a nineteenth century French ophthalmologist, a guy by the name of Louis Émile Javal. Javal had a lab at the Sorbonne, made some important contributions in the fields of astigmatism and eye tracking, and even developed an innovative device, the ‘Javal Schiötz Ophthalmometer,’ which measured the curvature of the corneal surface of the eye. But Liron was interested in something else he had done. A somewhat surprising finding about the way we read.

Liron Lavi Turkenich: He discovered something that applies to Latin, Latin letters (English, French, Italian, Portuguese). So if you only look at the top part of the letters, you can actually read them. And that was astonishing, and if you try at home to cover the bottom of the letters of the Latin alphabet, so the ‘a’ and the ‘b,’ you basically need only the top half. And I love this idea. And I just started doing this wild experiment, and I tried to see if it worked for Hebrew.

Mishy Harman (narration): It didn’t take long before Liron figured out that…

Liron Lavi Turkenich: Émile Javal was wrong about Hebrew. It doesn’t work like the Latin, but it works the other way around. So for Hebrew you basically need the bottom half in order to read. So most identifying characteristics are at the bottom. And this was extremely cool to discover. I loved it. I could basically read just by using the bottom part of the Hebrew. And then I checked if it’s working for the Arabic.

Mishy Harman (narration): Most of the information in Arabic, just like in the Latin scripts, is contained in the upper half of the letters.

Liron Lavi Turkenich: Well, if you think visually, you can imagine that if you only use the bottom part of the Arabic, the shape that comes out is a bit like waves. Basically, many many many letters have this bowl shape at the bottom and they look very similar. So you would need the top half.

Mishy Harman (narration): This realization – that for the sake of legibility, Hebrew only required the bottom and Arabic only the top, immediately got Liron going.

Liron Lavi Turkenich: The idea was to mix them into one experimental script – the top half would always be Arabic, and the bottom half would always be Hebrew. And that way, if you are used to reading Arabic, you would look at the top half of the letters, and if I would read Hebrew, I would look at the bottom half of the words.

Mishy Harman (narration): Liron began combining each one of Hebrew’s twenty-two letters with each one of Arabic’s twenty-eight, and forming six-hundred-and-thirty-eight entirely new hybrid letters.

Liron Lavi Turkenich: But it’s a whole new letter. It’s one coherent letter that looks like one letter that you’ve never seen before.

Mishy Harman (narration): I guess this is sort of like the typeface version of those mythological half-man-half-fish creatures.

Liron Lavi Turkenich: So I didn’t invent these letters, you know, from scratch. I kept the most essential parts of them, and then I merged them, or stitched them together.

Mishy Harman: And what did you call your mixed language?

Liron Lavi Turkenich: So I called it Aravrit, which is Aravit in Hebrew means Arabic and Ivrit means Hebrew. So it’s a hybrid of these two words. Just like this project is actually.

Mishy Harman: What was the first word you wrote in Aravrit?

Liron Lavi Turkenich: I wrote the word safa, language, ehh… I’ll show you. So this is safa…

Mishy Harman (narration): Liron pulled out her laptop and started showing us examples of Aravrit.

Liron Lavi Turkenich: Lura in Arabic.

Mishy Harman: OK, so what are we looking at?

Liron Lavi Turkenich: This is my font editor, this is how I design the typefaces and Aravrit. And in this software I can actually just move around the dots and change how the letters look. So this is how I work on it. Emmmm… Oh, I know, I know, I know what to show you…

Mishy Harman (narration): If you’re having a hard time visualizing Aravrit, just go to our website, we’ve posted some images and short videos.

Mishy Harman: Are there letters that were particularly problematic?

Liron Lavi Turkenich: Yes [Liron laughs]! So the ‘Ra,’ for instance, in Arabic, actually goes below the lines. So this is still giving me a very hard time, because the Arabic is supposed to be on the top! So each time there is Hebrew and then there is this one Arabic letter kind of sneaking into the Hebrew part, which is nice, I think, conceptually as well.

Mishy Harman (narration): In any event, you might think that Aravrit was labeled as a quaint left-wing naiveté and just ignored. But, well, friends, Aravrit became a cultural meme. A video clip about the project had millions of views, and tens of thousands of Israelis shared and liked it. Then, one day Liron was…

Liron Lavi Turkenich: Invited to visit the President of Israel. And I made in Aravrit a greeting for the Ramadan. And we brought two kids – one who is speaking Arabic and one who is speaking Hebrew – and they were supposed to paint the word and color it, and kind of offer this nice greeting from the President to the Arabic citizens.

Mishy Harman (narration): The two kids, seven-and-a-half-year-old Uriel Reifen from San Simon and seven-year-old Marian Faruja from Ein Karem, sat down…

Liron Lavi Turkenich: They looked at the piece of paper, and I just asked them, “oh, can you read this?” They’ve never seen these letters before, they’ve never seen the project before. And I was stunned because they could just read it, so easily. They did not make any effort. And this was the most emotional part of this project for me, I obviously started crying. And it was so sweet, the effortless way of them reading it. It was just so native to them. It was amazing. Yeah.

Mishy Harman (narration): Uriel and Marian actually became friends after that joint audience with the President, and have already had a playdate. It was, both mothers told me on the phone, a big hit.

Yochai Maital brings us the story of an unlikely love affair between Sarah, a Ukrainian formerly-religious Jew, and Tamer, a Palestinian dancer from Ramallah. As regional geopolitics makes their union nearly impossible, they retreat to a tent in the desert, living a carefree existence which seems to defy reality.

Act TranscriptYochai Maital: Where would you like to live?

Tamer: In Israel. By the sea..

Sarah: [Singing] Tel Aviv ya chabibi Tel Aviv… [Yochai and Sarah laugh].

Tamer: I grew up dreaming of the sea every night. I see it on TV, I see it on pictures, I see it on internet but I don’t see it in real life.

Yochai Maital: Have you ever been to the… to the beach in Israel?

Tamer: No. I did not because I never got the permit.

Yochai Maital: Are you scared?

Sarah: Umm.. Scared for him yes. For him mostly. And for me, because I… I… I can’t imagine him being harmed.

Tamer: It’s funny because I’m actually afraid for her. I’m scared of her giving up some chances because of this relationship. Living in this relationship you have to choose between future or love. If you choose love you’re kind of blind for the future because you never know what’s happening tomorrow.

Yochai Maital (narration): I can’t tell you exactly where I recorded this story. I can only say that it was in a sort of no man’s land, in the middle of the wilderness.

Tamer: Would you like coffee or tea?

Yochai Maital: Maybe coffee?

Tamer: Sure. Just let me make the fire.

Yochai Maital (narration): It’s not completely Israeli territory, nor is it exactly Palestine either. And it’s one of the most breathtaking places in the region, which is completely suitable, because the heroes of this story? Well, they’re just as beautiful as the scenery around them.

Sarah: We kind of don’t have other place to go for now. [Sigh].

Tamer: Yeah, if we want to keep our relationship going on, we have to live here. There is no other options.

Yochai Maital (narration): She is this tall blue-eyed fairytale princess, and he – a dashing Arabian prince. Both are barefoot and tan.

Sarah: My name is Sarah, I’m twenty-four years old. I’m from Ukraine, now I’m Israeli, Jewish. And I love this guy, Tamer. I don’t know where it will take me, we’ll see.

Tamer: I’m Tamer, I’m nineteen years old, I’m a Palestinian citizenship. And the love of my life is an Israeli Jew girl.

Yochai Maital (narration): Tamer was born in Be’er Sheva. The eldest son of a prominent Bedouin father. As a kid, his family moved around a lot.

Tamer: Jordan, Egypt, Syria, Palestine.

Yochai Maital (narration): Eventually they settled down in Ramallah, where the men in the family became high-ranking officers in the Palestinian security services. But Tamer didn’t exactly live up to his father’s macho expectations.

Tamer: I never felt right doing the same things that other kids are doing. I wanted to be the different kind.

Yochai Maital (narration): One day, when Tamer was thirteen, he went over to his neighborhood’s community center to meet up with friends, and play some ping-pong.

Tamer: But it was closed and there was the first dance class in the studio right next to us, and I just entered my head to check what’s happening.

Yochai Maital (narration): Tamer saw a group of people twirling, swaggering, making sudden bolts and free-flowing struts. His gaze was transfixed. The teacher, noticing his curiosity, well she walked over, and asked him if he cared to join.

Tamer: I told her it’s not nice.

Yochai Maital (narration): Coming from a traditional Muslim background – all those flailing arms and legs, gyrating torsi, and the tight-fitting dancing attire, it all seemed incredibly unwholesome.

Tamer: She told me, “OK, stay with us for a few days, do the movement and then leave.”

Yochai Maital (narration): Those few days, well they became months, then years. I guess you could say that Tamer, he’s, sort of, the Palestinian Billy Elliot.

Tamer: I wake up, and I’m going to regular school and I can’t wait to finish so I go dance. I go home, I’m watching dance videos and I’m postponing studying because I want to dance and read dance books. It became my happiness, my sadness, my anger, everything. Eventually dancing became my life.

Yochai Maital (narration): But he knew that this was not something that his dad would condone.

Tamer: So I told them I am in the football team.

Yochai Maital (narration): He kept up that lie for a long time.

Tamer: And after two years I was home but I didn’t know that the football team that I was supposed to be in, is having a big match and I was home just relaxing at the TV. And then they discovered that I’m not in the team because they were actually planning to go to the football match but I was home.

Yochai Maital (narration): They tried to force him to quit, but Tamer was set on dancing. Begrudgingly, they learned to live with a son who was more at home in a dance studio than at the mosque, who preferred a cold beer to sweet tea. A son that was mingling with the bohemian artsy scene of Ramallah. But there were red lines he hadn’t yet crossed.

Tamer: I was in a bar in Ramallah having a beer. And I see a beautiful girl in the table next to me, also having a beer.

Yochai Maital (narration): We’ll get back to that scene at the bar a little later, but for now, let’s travel due north some two thousand kilometers, to Kiev, Ukraine, where ten-year-old Sarah (she had a totally non-Jewish, Russian-sounding name back then) was trying to figure something out.

Sarah: Our family looks different. Our mentality is a bit different from the Ukrainian ones, but though we don’t have other religion, like we are not religious family, we don’t have another language, so why we are different? I never understood really.

Yochai Maital (narration): But she was about to. You see, her father took her on a family trip to Poland, to this place called…

Sarah: Auschwitz, to the concentration camp and he tell me everything.

Yochai Maital (narration): There, among the ashes, the discarded baby shoes, and the teenagers wrapped in Israeli flags, he started recounting old and seldom-told family stories.

Sarah: About his family that they were persecuted in the wartime and they also were in the camps. I felt myself, like I felt like it’s part of me.

Yochai Maital (narration): Growing up, Sarah often heard anti-Semitic remarks being tossed around school, but she never really paid them too much attention. After she got back from Poland, things started to change. Suddenly those remarks were pointed directly at her.

Sarah: “Are you Jewish?” I say, “yeah like part of my family are Jewish.” “Wow, like, what a shit, like what a shit you have in your life.” Or, “yeah, like, we really are disappointed that Hitler didn’t kill all of us. Like he would clean up this place from all the shit like you.”

Yochai Maital (narration): Sarah decided that if she was going to be on the receiving end of such remarks, she might as well know something about the group she was now being identified with.

Sarah: Girls are usually, like not prohibited… but they don’t learn Talmud but I did this, I just was going to Beit Midrash in Ukraine and sitting with boys and telling, “I stay here and I learn.” And eventually they said, “OK.” And I discovered something very beautiful that I belong to.

Yochai Maital (narration): As Sarah was slowly becoming more and more religious, she began feeling something that so many Jews over the generations had experienced before her.

Sarah: I felt kind of not welcomed at the place I was born and raised in.

Yochai Maital (narration): And on top of that..

Sarah: When I became religious, my family kind of cut from me.

Yochai Maital (narration): Sarah’s family were fervent atheists. And this new version of her, as a pious woman in long skirts… It felt foreign and threatening. They wanted nothing to do with her. Feeling basically alone in the world, Sarah decided it was time for a change of scenery. When she turned eighteen, she moved to Israel, and landed in a Charedi ulpena, or all-girls boarding school, in Jerusalem.

Sarah: I was really really observing. And I was doing it from my heart.

Yochai Maital (narration): But then all kinds of small things started bothering her.

Sarah: When I came there I discovered that they don’t learn anything. They just said, “TV is bad, you have to wear the big thick socks in the summer because it’s good.” And I couldn’t stand this style, so I wanted to break it. I didn’t want my life to continue like this.

Yochai Maital: Amm…

Sarah: And that’s what I did. I started giving up observing things little by little. I felt very strange with it after six years of strict observing.

Yochai Maital (narration): Despite making many good friends, Sarah left the ulpena.

Sarah: And then once more, I see myself totally alone and I have to build everything from the beginning. I don’t know what to do, like I don’t have anybody here. I have to pay the rent. I just understood ‘I’m fucked here.’

Yochai Maital (narration): Around this time Sarah started hanging out at this hummus bar in Jerusalem.

Sarah: So I was sitting there a lot and guys there they just offered me to work there. And I told them, “OK.”

Yochai Maital (narration): The place was owned by Arabs from East Jerusalem, and that’s also where most of the people working there were from. For Sarah, this was the first time she had any meaningful interaction with Arabs.

Sarah: And they proved to be very very nice. And two of them were also actors and dancers of Dabke. And they invited me to come for their show in Ramallah. And I thought, ‘I come to Ramallah? Mmmmm… OK I’ll come to Ramallah, no problem.’ [Sarah laughs].

Yochai Maital (narration): Sarah went to that Dabke performance, and she had a great time. After that, she’d return every now and then, and sit in local cafés and bars.

Sarah: I just saw a lot of young people dressed like me, talking like me. I discovered that there’s another world like so close to us. And they know nothing about us, we know nothing about them.

Yochai Maital (narration): I thinks it bears mentioning here, that Sarah wasn’t, and still isn’t, some kind of political activist, or a peacenik.

Sarah: I wouldn’t even tell about myself that I’m leftist. Not at all. I support the Israeli State, I think there should be a right for Jews to live in the place that are historically connected to and to build their destiny as a nation.

Yochai Maital (narration): So it wasn’t politics that drew Sarah to Ramallah. It was something else, something more personal.

Sarah: I felt myself kind of rejected in Israeli society. Because I was religious in the past, not really knowing the codes of the secular Israeli society and I just felt more welcomed in Ramallah…

Yochai Maital: Hmmm…

Sarah: For real. Back in Ukraine, Jewish help the Jewish, here not. I discovered that it doesn’t really play a big role that you’re Jewish. This trick doesn’t work here.

Yochai Maital (narration): But somehow in Ramallah, she discovered a place where people were friendly, and, as she felt back then – non-judgmental. Sarah fell in love with the scene. She kept going back, and making new friends. And that brings us back to that night at the bar.

Tamer: I was in a bar in Ramallah having a beer. And I see a beautiful girl in the table next to me, also having a beer.

Sarah: Yeah, he was sitting in another corner with his friends and looking at me from time to time.

Yochai Maital (narration): Tamer waited for an opening, an accidental glance, a half smile, anything. But she wasn’t paying him any attention.

Tamer: So I stole her lighter.

Yochai Maital (narration): Tamer asked her for a light, and then “forgot” to give it back. A few minutes later, Sarah came asking for it and they started talking.

Sarah: Yeah and I liked him, I don’t know to describe it. I just ahhh… He’s optimistic, he’s funny, he’s very courageous.

Yochai Maital (narration): In any case, the bottom line?

Tamer: She gave me her number. But she stopped using the same number she gave me.

Yochai Maital (narration): Tamer tried calling, and never got an answer. For a while he’d search for her in bars and on the street. And then, almost two months later…

Tamer: I receive a message at 3:21 am. “Asleep?”

Yochai Maital (narration): Dazed, Tamer replied:

Tamer: “First, yes? Second, what? Third, who?”

Yochai Maital (narration): Sarah quickly wrote him back.

Tamer: “I’m sorry for waking you up.” And I thought, ‘what a nice person.’ And I texted her back, “it’s OK, I wanted to wake up at that time.” [Yochai and Tamer laugh]. And after a while I receive a message, “how are you” and I reply “thanks and you? etc.” And it keep texting and texting and texting.

Sarah: He told, “are you Jewish?” I told him, “yes!” “Are you Israeli?” “Yes!” “Ah! It’s OK.” [Sarah laughs].

Tamer: We kept texting, texting and I can feel a little bit of love in the text.

Yochai Maital (narration): Sarah and Tamer started going out. And eventually she moved to Ramallah to be closer to him.

Sarah: In the beginning I was very happy because everything’s so different and food is good and cheap. Then suddenly I became discovering that he was telling me, “OK, you can’t kiss me, even on the cheek.” Like, we are in the bar, “you can’t hug me too much. We can’t sit in a public place like a park.” You don’t feel yourself free.

Tamer: I remember telling her and every time seeing her face being shocked like ‘why?’ And everytime I… Me not able to explain her. Because I don’t believe in whatever I’m telling her. But I know that we’re forced to do it.

Yochai Maital (narration): But not being able to sit together on the park bench, that turned out to be the least of their worries.

Tamer: For my family, of course, it’s a problem. So in the beginning, she was just a European, a Christian European.

Sarah: I have to say, “yeah, yeah I’m from Ukraine,” to invent all these fake stories, to remember what was back in Ukraine and I felt myself shit. I found out I’m living fake life.

Yochai Maital (narration): But his friends were asking questions.

Tamer: “OK, what was she doing in Israel for six years? How come she speaks Hebrew? Does she have the passport? Oh, so she’s an Israeli citizenship. Is she a Jew? Okay, she can’t come to Israel if she’s not a Jew, so she’s a Jew – you must leave her. You must stop.”

Yochai Maital (narration): Inevitably, his family caught wind of the rumors.

Sarah: They were threatening him, and they were like talking about me like, “stop being with this Israeli Jewish bitch, sharmuta.” And I was literally very scared for him.

Tamer: I was scared as well because I knew that we’re in the place that does not support this relationship. And I knew that in a place that you’re not really protected, all kinds of things can happen to you.

Sarah: I told him, “no way me living here anymore. I can’t live like this, you should either cut with them either cut with me.” And he told me, “OK, so where are we going?”

Yochai Maital (Narration): As an Israeli citizen, it’s actually illegal for Sarah to be in Ramallah, which is categorized as Area A – a zone under complete Palestinian control. Tamer, can’t legally cross the Green Line. There’s literally nowhere they can be together.

Sarah: So we went to live in the desert, in the nature. Like we can’t live in the city on the West Bank. We are not accepted there and also in Israel we are not accepted. So the only place is a tent.

Yochai Maital (narration): And this brings us, finally, to today. Tamer and Sarah have fled. His family is looking for him, sending ominous messages threatening to hurt him if he doesn’t leave his Jewish partner.

Tamer: So we live in our zula which contain two tents, one tent is for me, for Sarah and the cat to sleep in. And the other tent is our storing room, we have the clothes, we have the blankets. A living room which have the food, nescafé, café, tea [Sarah laughs] and milk. And all kinds of drinks you want.

Yochai Maital: And what do you guys live off of?

Sarah: Ahhh… he selled his playstation. And I had some money from before. But I would say we don’t spend a lot here because we are buying just rice and vegetables. And we are cooking so it’s not a lot of money.

Tamer: We decided together that, ‘let’s run out of money.’ And the money we have is enough until three-four weeks. And everyday we’re thinking where we’re going next because we can’t live in nature anymore because it’s so hot.

Yochai Maital (Narration): The temperature in the area where Tamer and Sarah have pitched their tents, can reach above fifty degrees celsius in the summer, that’s like one-twenty-two fahrenheit. Tamer told me that despite the heat, the dust, the intimidating messages from his family, he’d follow Sarah anywhere.

Yochai Maital: It’s both terribly romantic what you’re saying and terrifying.

Tamer: I would totally agree with you, yes. Right now I’m kind of family-less, friends-less and place-less because of this relationship because no one want a Palestinian in a relationship with an Israeli Jew. But I don’t know, my love to her is way stronger than all this things, so I took the decision of allowing myself to fall in love with her.

Yochai Maital (narration): At the end of our interview, after I closed the recorder and packed up my gear, Sarah turned to me and asked a very direct question: So now that you’ve heard our story, what do you think? Is there any hope? I looked at her and then at Tamer, at their beauty, at their youth. I took a last sip of the black coffee they had made for me on the fire that was still fizzling out in the corner. And I thought to myself that if anyone has a chance, it’s these two. I mean they’re so in love, they’re so brave, and have already been through so much together. I wish I would have just said yes. But I didn’t. I didn’t because it seemed hypocritical and – as beautiful as they, their story and the mesmerizing desert sunset around us all were – deep down I feared that reality would prove too difficult for them. That, sooner or later, they’d crash. You know, in our line of work we tell stories. We meet people, listen to them, and then we go home, and we think about how best to present their tales. We have a lot of control, really. I mean we can edit out certain aspects, we can choose how – and when – to reveal others. But we can’t control the facts, the outcomes, or the endings of our stories. And sometimes, I wish we could. There are occasional IDF patrols in the area where Tamer and Sarah pitched their tents. They’ve caught Tamer a few times in the past, and let him off with a warning. See, he is what’s called a Shohe Bilti Chuki, an illegal alien, and as such he isn’t allowed to set foot in Israel. One day, recently, as Sarah was out collecting firewood, the soldiers came by again. When she returned to their tent, Tamer was nowhere to be found. A couple of days later, she received a text message: “I was caught by the police,” it read. “I will be investigated in Ramallah tomorrow. All my papers – my ID, my passport – everything, was taken. I don’t know what else to say.” Depressed, tired and heartbroken, Sarah didn’t want to stay in the tent alone, waiting around for an uncertain future. So she booked an open-ended ticket to Norway.

[Song]

The original music in this episode was composed and performed by Eran Zamir, Ruth Danon, Nili Fink and Noam Sadan. The final song, ‘Tamally Ma’ak,’ is by Amr Diab and covered here by Tsahi Halevi. Ahmed Ali Moussa wrote the lyrics and Tag Sherif composed the music. The episode was mixed by Sela Waisblum.