Israel’s Declaration of Independence was forged amid strife and turmoil. It was a birth that, everyone knew, would trigger war. Yet it was also a rare moment of unity and agreement. A joint historical, cultural, legal and – to a certain extent – religious case for a Jewish State in the Land of Israel. Today, this document looms large once again, and has emerged as a central point of contention as we Israelis debate the future character of our country.

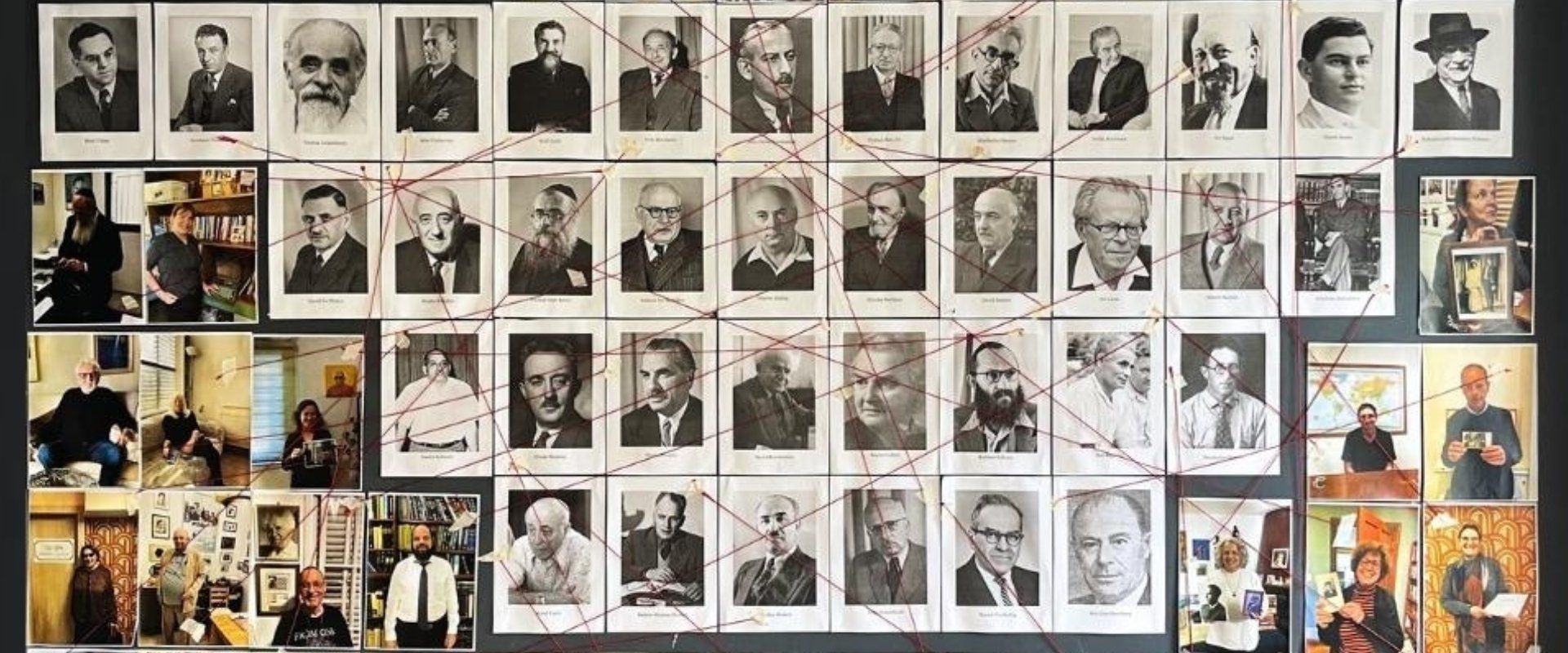

Thirty-seven people signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut. There were no Arabs, and for that matter no non-Jews, among them. But the group that did sign represented many factions of the Jewish population: There were Revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

In the introduction to the series we meet Ruti Avramovitz, Israel State Archives’ Chief Archivist, who takes us straight to the source, and grants us a rare glimpse of the Holy Grail itself.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Hi Israel Story listeners, it’s Mishy.

One of the very first decisions we made here at Israel Story – long before we had a name, a single story idea or even, for that matter, a recording device – was that the show was going to be apolitical. And more or less ever since we made that decision, twelve years ago, we’ve been trying to understand what – exactly – that means.

Certain aspects of being apolitical have always been straightforward and easy. There have been seven election cycles since the show began, and not only have we never endorsed a party or a candidate, I think we’ve barely even mentioned the fact that elections were taking place.

Other parts of being apolitical, however, have been murkier. We’ve asked, and never quite found clear answers, to many pertinent questions. For instance, do we avoid stories that relate to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict altogether, or – if we don’t – how do we choose which stories to tell? Do we tell stories of people who live beyond the Green Line, and if so, does that include only Jewish settlers, or also Palestinians? And what terminology should we use – West Bank? Judea and Samaria? Occupation? Palestine? Palestinian Authority? Israeli-Arabs? Palestinian citizens of Israel?

Widening the lens just a bit, the very notion of being apolitical is complicated. See, somehow, in the Israeli context, “political” really means one thing, and one thing only – what you think about the conflict. But, as many smart people have said for centuries – at the end of the day everything is political. Airing a story about the Women of the Wall or a trans rabbi? About the charedi response to COVID or a women’s volleyball team in Nazareth? About the history of pork consumption in Israel or the breakup of a kibbutz? These are all political statements in one way or another.

So the eleven seasons of our show have been a continuous balancing act, a delicate dance, with endless internal debates, countless compromises, and an array of ad-hoc solutions. Over the years we haven’t always succeeded. A couple of times we lost funding as a result of a story that went “too far” in one direction or another, and – what’s even worse – here and there we alienated listeners who felt that their point of view wasn’t being heard.

But we do try, as best we can, to be aware of our biases, and to balance them. To represent a wide variety of voices and opinions and places, and to hire an increasingly diverse staff of producers. We keep detailed spreadsheets of who is, and also who isn’t, getting air time on the show.

It’s never going to be perfect, but each year we ask you whether you think we have a political bent, and survey after survey somewhere between ninety-one and ninety-four percent of you say that you think we’re an honest broker. What makes me even happier is that the remaining six to nine percent – those who think we do have a bias – are more or less split between those who are convinced that our show is left-leaning and those who are sure it’s right-leaning.

Now, being apolitical is not a goal in and of itself. At least not for me. As you can well imagine, I – and each one of the team members here at Israel Story – have political opinions, even strong and outspoken ones. We care deeply about this country of ours, which is probably why we’re drawn to create the show in the first place.

But the reason to adhere to this apolitical path is that it allows us to listen – to actually listen – to the stories of others. Even those we disagree with. It allows us to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. And it helps us bring these stories to a wide and diverse audience. See, just as you’re listening to these words right now, so are many many other people, in more than 190 countries around the world. And that group of listeners? It includes Jews and non-Jews; religious and secular and everything imaginable in between; socialists and capitalists; conservatives, moderates and liberals; ardent Zionists and supporters of BDS. Really a bit of everything. And just think about that for a second – in our hyper-fragmented world, in which each ideology has its own media, its own narratives and its own truth – getting such a diverse group of people to listen to the same stories about a polarizing place like Israel? It’s a minor miracle.

The only way we can do that – the only way – is by sticking to our most fundamental tenet: That a person is a person is a person, no matter what, and that we’ll only learn and grow by listening to each other. And even that, of course, is – sadly, and increasingly – a political statement.

So why am I telling you all this?

Well, because this spring Israel will be celebrating its seventy-fifth anniversary. And for a very long time we’ve been thinking about how best to mark that milestone. Our mission, from the start, was to expose listeners to the complexity of life here. To celebrate the richness and diversity of the local population. But it was never, and isn’t now, to celebrate Israel. We don’t work for the government, and don’t receive any governmental funding. We release tales that – at least we hope – explore the nuanced reality of Israeli society. And we leave it to each and every one of you to draw your own conclusions. Some will feel that the show strengthens their connection to Israel, others that it reminds them of its shortcomings.

Mishy Harman (narration): This Yom HaAtzmaut obviously comes at a critical moment. Israel appears to be at a crossroads. Questions of national identity, religion, unity, democracy, the rule of law — the very questions that Israel’s founders wrestled with — are all at the forefront.

So, with that, how do we go about marking the seventy-fifth Yom HaAtzmaut? For months we went back and forth, trying to strike the right chord. After all, we spend our days traveling up and down the country, talking to people, hearing their stories, their fears, their dreams. And, of course, we’ve noticed – long ago – how different the life of a yeshiva boy in Bnei Brak is from that of a Bedouin teacher in Hora. How dissimilar are the Israels of a farmer from Emek Yizrael, an Arab fisherman from Akko, a high-tech exec from Herzliya and a nurse from Dimona.

And those differences? It seems as if they are just growing. That the gaps are simply widening.

We fight and we disagree. We call each other names and we hate. We demonstrate and we demonize.

So what is it, aside from the fact that we are all physically here, that unites us? That makes us part of this group we call Israelis?

To answer that question, we decided to go back to the basics. To what was seemingly the first and last time there was some form of national consensus about… anything.

Our new series is called Signed, Sealed, Delivered? and it looks at our founding moral compass – Megillat Ha’Atzmaut, or the Declaration of Independence.

Mishy Harman (narration): On May 14th, 1948, eight hours before the end of the British Mandate in Palestine, David Ben-Gurion declared the birth of a new state, which in a meeting two days earlier received its name – Israel.

The ceremony itself, which took place in the Tel Aviv Museum – the former home of Tel Aviv’s first mayor, Meir Dizengoff – was kept secret till the very last minute. But of course, in such a small country, word got out and masses lined Rothschild Boulevard and the nearby streets. They looked on as members of Mo’etzet Ha’Am, the pre-state governing body, and other lucky dignitaries who managed to score a much-coveted invitation, entered the building. Everything was done in such haste that the graphic artist, Otte Wallisch, who had been tasked with designing the scroll of the Declaration of Independence, had only managed to complete a couple of paragraphs of calligraphy. So David Ben-Gurion read most of the text off of a printed piece of paper, and then – after Rabbi Maimon recited the She’He’Cheyanu prayer – each member of the provisional government in attendance got up and signed their name at the bottom of the scroll. This didn’t stop them, two days later at the very first meeting of the Provisional State Council, from voicing many complaints about the text – about what was included and what was omitted.

Now we began this project long before this most recent and dramatic wave of legislation and protests. And one of the most interesting elements of the resistance to the judicial reform is the resurgent centrality – and deep relevance – of Megillat Ha’Atzmaut.

Mishy Harman (narration): Suddenly Megillat Ha’Atzmaut is everywhere. A massive replica was hung on the building of the Tel Aviv municipality, there are bumper stickers and t-shirts that say Ne’emanim Le’Megillat Ha’Atzmaut – loyal to the Declaration – and multiple initiatives to get citizens to electronically sign the scroll.

For months we’ve been trying to get a glimpse of the real Megillat Ha’Atzmaut. And it turns out it isn’t a simple task.

Megillat Ha’Atzmaut is kept at the Israel State Archives, and is taken out of the vault very rarely. We wrote emails, called in favors, pleaded and then, when we were just about to give up, we were summoned to the Archives, though we weren’t sure whether that meant our request to see the scroll had been granted.

As it happens, the State Archive’s storage facility is about a three minute walk from Israel Story’s offices, in Talpiot, in Jerusalem. Looking at the nondescript building from the outside, you’d never in a million years guess that it houses some of the country’s most priceless treasures. It looks like a faceless and industrial warehouse. Our producer Mitch Ginsburg and I arrived a few minutes early. Mitch locked his bike to the railing up front, and we entered through a tiny side door – because, well, there didn’t seem to be any other visible entrance. We were ushered into a lab that had all kinds of machines and stacked boxes of documents. And there, on a plain plastic table, lay a long rectangular blue box. And inside it, we suspected (but weren’t totally sure), was the Holy Grail itself.

To be honest, the whole thing looked a bit like a morgue.

Mitch Ginsburg: It’s pretty cool with that light. It would be nice to have it, I like the way that it’s laid out like a cadaver almost.

Mishy Harman: [In Hebrew] Yeah.

Mishy Harman (narration): Since there were a ton of air conditioners and vents making a lot of noise, we asked if we could relocate to a quieter side room. And then, to our surprise, they not only agreed, but asked us to help schlep the Megillah.

Mitch Ginsburg: Mishy, how does it feel carrying the Declaration of Independence around?

Mishy Harman: It’s above my pay grade.

Mitch Ginsburg: I think so… [Sound of clank].

Mishy Harman (narration): Don’t worry, that was most definitely not the sound of the box with Megillat Ha’Atzmaut falling. It was, instead, us entering the office of Ruti Avramovitz, the Director of the State Archives, who carefully moved her cup of tea, you know, so as to avoid a national catastrophe.

Ruti Avramovitz: OK, my name is Ruti Avramovitz, I’m the Chief Archivist. We are currently at the National Archives, where all the materials are, the historic materials. And lay next to us is the Declaration of Independence of the State of Israel.

Mishy Harman: Is the Declaration the star of the collection? Is it the most prized possession within the… in the Archives?

Ruti Avramovitz: Well, yes. I think you can say that. If I will have to choose one particular document from the Archives, and we have 400,000,000 [Mishy laughs] documents in the Archives, then I would probably choose this particular item as the most important one that we have. It is kept in a safe in a very dark room, in a very dark box, that hopefully will keep it safe for eternity.

Mishy Harman: But you know, it’s interesting because actually the preservation… given the… this is a seventy-five-year-old document the preservation is quite amazing. I mean, you know, it looks as though it’s…

Ruti Avramovitz: Was written yesterday.

Mishy Harman: Yeah, it looks as if it’s a relatively new document. I mean it’s true that there’s some fading in the signatures, but…

Ruti Avramovitz: Emm hmm.

Mishy Harman: But the ink of the Declaration itself is very strong and vibrant.

Ruti Avramovitz: Emm hmm. Thank you! We do really our best to preserve and protect the scroll.

Mishy Harman (narration): Ruti explained that getting to see the scroll itself is a big deal.

Ruti Avramovitz: You know, it’s a very special occasion that you are here in this actually very secure building and to come here and also to see the scroll is double rare occasion. So really, not many people. Really. We can count them on fingers.

Mishy Harman: Really?

Ruti Avramovitz: [In Hebrew] Yes. And I can understand if someone will say that this is not the Archive’s possession. It’s not the Archive’s possession, it’s not the Archive’s document, it’s the Archives of the people of Israel. I agree. It belongs to us all. I totally agree. We will just have to find the way to present it to as many people as we can.

Mishy Harman (narration): There are indeed plans to present it publicly in the future. But Ruti? She’s worried about that.

Ruti Avramovitz: Just because I’m afraid that it might get stolen or something terrible will happen to it because it’s a unique document. There is no other. They didn’t make two of them.

Mishy Harman: So Ruti, for me this is the first time, of course, that I’m seeing Megillat Ha’Atzmaut, the Declaration of Independence, and it’s… it’s almost a mystical sensation that I have, because it’s something that I’ve seen images of my entire life. But to see the actual artifact itself, is something quite special. Do you recall the first time you saw Megillat Ha’Atzmaut?

Ruti Avramovitz: To tell you the truth, the very first time that I saw it, I was a little bit disappointed because it’s so small.

Mishy Harman: Really?! To me it looks large, no? [Ruti laughs].

Ruti Avramovitz: It’s… maybe it’s long, but it’s quite small. Quite humble. And although it’s small, to me, its content is very powerful. Just to think that it took them only three weeks to write. I think of documents that we write these days, and it takes us sometimes months, really months, and to think that this very important document took them only three weeks and four sessions and that’s it, that’s amaze me, and I think it tells me how much we are different than the people we used to be.

Mishy Harman (narration): Later on in the series, we’ll have a piece devoted to the various different drafts of the Declaration, and the unlikely story of how the final text came to be. We’ll talk about the battles between a religious statement and a human-rights-based secular one. About the compromises that were made, and the two most significant words that were left out of the document – ‘God’ and ‘democracy.’

But for now, just think about it a second – the British are about to leave the country, the future is entirely unknown, the violent clashes of what will later be known as the War of Independence are escalating (by the end of the war, one percent of the Jewish population will have been killed) and here, within three weeks and a few short sessions, a very diverse group of Jews somehow agree on a text that will serve as the foundational document of the new state.

Ruti Avramovitz: The scroll is three parts combined together, right? You can see the stitches. Ben-Gurion signed first, but then it was the alphabetic order, you see?

Mishy Harman (narration): Thirty-seven members of Moetzet Ha’Am, the provisional legislative body of the Yishuv, signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut. Twenty-five of the signatories were present at the May 14th ceremony in Tel Aviv, eleven were stuck in besieged Jerusalem and added their signatures later, and one – Rabbi Yitzhak-Meir Levin – was in the States at the time, and signed upon his return.

There were no Arabs, and for that matter no non-Jews, who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut. We’ll address that lacuna in a special installment of the series.

But the group that did sign the document represented many factions of the Jewish population: There were Revisionists and Labor Party operatives; there were communists and socialists and capitalists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists; thirty-five men and two women; thirty-five Ashkenazim (mainly Russians and Poles) and two Mizrachim (one Sepharadi and one Yemenite); there were twenty-two who were born in the 19th century, and three that were under forty. There was a single signatory who had been born in the Land of Israel and one whose mother tongue was Hebrew.

Over the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories. Fourteen of the thirty-seven have children who are still alive, all the rest have grandchildren, or great-grandchildren, or nieces and nephews.

And we traversed the country, booked studios around the world, and one by one, we interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

At the outset, we didn’t know who these descendents would be, or what they would believe. Would they think like their forebears or had they forged their own, perhaps even opposite, ideological paths? Did they live in Israel, and if not, why? We were curious to see if they’d be more, or rather less, representative of Israeli society than the original group of signatories. And whether, knowing what they know about Israel today, they would have signed the Declaration themselves.

The result, which we’ll bring you over the next couple of months, is – in certain ways – a sociological study. But it’s also an intensely intimate document. People remembering their parents, their grandparents, their uncles.

You know, it’s easy to forget just how young a country Israel is. True, none of the thirty-seven men and women who signed Megilat Ha’Atzmaut are still alive. The last one, Me’ir Vilner, died in 2003.

But compared to the States, for instance, where all the signatories of the American Declaration of Independence have long ago moved into the realm of historical figures, here there’s a sense that we can still touch our founding fathers and mothers. We can still get a first-hand sense of who they were as people. At home. With their family.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

Mishy Harman: So the last question that I’ll ask you, Ruti, is just what does it make you feel to be so close? I mean we can… I’m not going to do it, but we could really touch it, right now, with our fingers. What does it make you feel?

Ruti Avramovitz: The answer is very short. It makes me feel like wanting every, every citizen, every child in Israel to read this document and to really understand what it says. It says everything about who we are and who we want to be. And it’s been saying it for seventy-five years now, but not many of us ever read this document and I think that if many people, hopefully all of us, will read this document, we will understand a little bit more, and a little bit better, about who we are without anyone telling us who we should be. That’s it.

Mishy Harman (narration): The episodes of this series are going to be different than our usual brand of human-interest storytelling. To begin with, they’re much shorter, and aren’t exactly stories in the normal Israel Story style, but rather a collection of short portraits and edited interviews. Israel Story, of course, isn’t going anywhere. Our normal episodes will pick up again after the series, and we have many wonderful tales in store. But in honor of the seventy-fifth anniversary, and in light of the dramatic times we’re experiencing here in Israel, we’re going to devote the coming weeks to the descendants of the signers of Megillat Ha’Atzmaut. Each descendant will receive their own “mini-sode” that together, we hope, will form a mosaic of who we were, who we are, and who we wish to be.

Zev Levi scored and sound designed this episode with music from Blue Dot Sessions.

It was recorded at Nomi Studios and mixed by Sela Waisblum. The end song is Ein Li Eretz Acheret (“I Have No Other Country”), which was written by Ehud Manor, arranged and sung by Corinne Allal.