Herzl Rosenblum was born in 1903, a year before the death of his namesake, Theodor Herzl, who – of course – was also a journalist. In so naming him, Rosenblum later remarked, his parents had left him little choice but to spend the rest of his life in service of the Zionist cause.

In his autobiography, he claimed that he had never met two people more different in both temperament and character than his own parents. His father, Avram Motl, was an eternal optimist and a fervent Zionist, whereas his mother, Rode Iteh, was an ardent Bundist with such a bleak outlook on life that he referred to her as “Schopenhauer in a dress.”

Though he was a public figure his entire life, Rosenblum’s career as an elected politician was brief. It began (and promptly ended) when he was in high-school, in Kaunas, where – as head of the student union – he organized a general strike. Given that three-fifths of the school’s student body was Jewish, he noted, the language of instruction ought to be the ancestral tongue of the Jews – Hebrew. He made it clear that till his demands were fully met, not a single Jewish student would enter the classroom. But things didn’t go as planned. Within a few days, almost all the other Jewish pupils had broken ranks, Rosenblum himself had been deposed as head of the student union, and – as if all that wasn’t enough – he was expelled. It was only thanks to a desperate plea from his highly-respected older brother that he was eventually allowed to return to school, matriculate, and go on to study at the University of Vienna.

In 1935, after stints in both Paris and London, and armed with a doctorate in law, he moved to Palestine with only one firm conviction in mind: not to work as a lawyer. Without any real knowledge of Hebrew and with no experience whatsoever as a journalist, he met with Yosef Haftman, the editor of the HaBoker daily, and asked him to accept dispatches from the upcoming Zionist Congress in Lucerne, to which Rosenblum had been invited as a participant.

Haftman agreed, and the deal was that Rosenblum would be paid if, and only if, HaBoker actually ran the articles. Realizing that this was his one shot, Rosenblum went all in: He took notes, drafted, crafted and had the pieces translated into Hebrew on his own dime. To his delight, the effort paid off and Haftman, the editor, bought all ten of his dispatches. That ultimately launched Rosenblum’s career, which would include a 38-year stint as editor-in-chief of Yedioth Ahronoth, one of the country’s most popular newspapers.

Ideologically, Rosenblum was a disciple of Ze’ev Jabotinsky – the Odessa-born journalist and orator whose writings laid the cornerstone on which the Israeli right was founded. In a 1986 interview, he called Jabotinsky the greatest journalist the world has ever known, and said that, “my entire career as a publicist I have lived under the spell of his enchanting power.”

As one of only three Revisionists to sign the Declaration of Independence, Rosenblum was a staunch right-winger. In his editorials he opposed the 1952 reparations agreement with Germany and – later on – avidly supported Jewish settlement in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Sinai Peninsula. He often argued that peace would only come once the Arab citizens of Israel “accept that they will, with full equal rights, forever be a minority in the State of Israel.”

He retired from Yedioth Ahronoth in 1986, and two years later lit one of the torches in the central ceremony celebrating Israel’s 40th birthday. He died in Tel Aviv in 1991, at the age of 87.

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: there were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

Today we’ll meet Herzl Rosenblum, and his grandson, Doron Rosenblum. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Act TranscriptDoron Rosenblum: Now, before the ceremony began, Ben-Gurion called him aside and told him, “Dr. Rosenblum, I have a request.” So my grandfather said, “yes, what is your request?” He said, “you know, this is a very important day. And this Statement of Independence is going to stay with us for many, many years. And I think that signing by the name of ‘Rosenblum’ is not the right thing. Because this name is basically — has to do with the diaspora. I would like you to sign with an Israeli name.” So my grandfather told him “yes, but my name is Rosenblum, and my father was called Rosenblum, and his father before was called Rosenblum, so I’m not sure exactly what are you asking me to do and I don’t feel really comfortable with it.” But Ben-Gurion was very insistent, and he told him “please, reconsider. I really would be happy if you can sign by the name of ‘Vardi.’” Now ‘Rosenblum’ is the bloom of the roses, and ‘Vardi’ — vered in Hebrew — is also a rose. So basically, he translated his name for him. And my grandfather decided that he just doesn’t want to argue with Ben-Gurion. And this is how he signed by the name of ‘Dr. Herzl Vardi.’

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Doron Rosenblum, the eldest grandchild of Herzl Rosenblum (AKA Herzl Vardi), a Revisionist and a prize-winning journalist who stood at the helm of the Yedioth Ahronoth daily for no less than 38 years, a period during which he penned – wait for it – some 11,400 editorials.

[Signed, Sealed, Delivered? introduction]

Today we’ll meet Herzl Rosenblum, and his grandson, Doron Rosenblum. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Here’s The Times of Israel’s founder and Editor-in-Chief, David Horovitz, with Doron Rosenblum, Herzl Rosenblum’s grandson.

David Horovitz (narration): Herzl Rosenblum was born in 1903, a year before the death of his namesake, Theodor Herzl, who – of course – was also a journalist. In so naming him, Rosenblum later remarked, his parents had left him little choice but to spend the rest of his life in service of the Zionist cause.

In his autobiography, he claimed that he had never met two people more different in both temperament and character than his own parents. His father, Avram Motl, was an eternal optimist and a fervent Zionist, whereas his mother, Rode Iteh, was an ardent Bundist with such a bleak outlook on life that he referred to her as “Schopenhauer in a dress.”

Though he was a public figure his entire life, Rosenblum’s career as an elected politician was brief. It began (and promptly ended) when he was in high-school, in Kaunas, where – as head of the student union – he organized a general strike. Given that three-fifths of the school’s student body was Jewish, he noted, the language of instruction ought to be Hebrew, the ancestral tongue of the Jews. He made it clear that till his demands were fully met, not a single Jewish student would enter the classroom. But things didn’t go as planned. Within a few days almost all the other Jewish pupils had broken ranks, Rosenblum himself had been deposed as head of the student union, and – as if all that wasn’t enough – he was expelled. It was only thanks to a desperate plea from his highly-respected older brother that he was eventually allowed to return to school, matriculate, and go on to study at the University of Vienna.

In 1935, after stints in both Paris and London, and armed with a doctorate in law, he moved to Palestine with only one firm conviction in mind: not to work as a lawyer. Without any real knowledge of Hebrew and with no experience whatsoever as a journalist, he met with Yosef Haftman, the editor of the HaBoker daily, and asked him to accept dispatches from the upcoming Zionist Congress in Lucerne, to which Rosenblum had been invited as a participant.

Haftman agreed, and the deal was that Rosenblum would be paid if, and only if, HaBoker actually ran the articles (even then, I guess, journalism was a rough gig). Realizing that this was his one shot, Rosenblum went all in: He took notes, drafted, crafted and had the pieces translated into Hebrew on his own dime. To his delight, the effort paid off and Haftman, the editor, bought all ten of his dispatches. That ultimately launched Rosenblum’s career, which would include a 38-year stint as editor-in-chief of Yedioth Ahronoth, one of the country’s most popular newspapers.

Ideologically, Rosenblum was a disciple of Ze’ev Jabotinsky – the Odessa-born journalist and orator whose writings laid the cornerstone on which the Israeli right was founded. In a 1986 interview, he called Jabotinsky the greatest journalist the world has ever known, and said that, quote, “my entire career as a publicist I have lived under the spell of his enchanting power.”

As one of only three Revisionists to sign the Declaration of Independence, Rosenblum was a staunch right-winger. In his editorials he opposed the 1952 reparations agreement with Germany and – later on – avidly supported Jewish settlement in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Sinai Peninsula. He often argued that peace would only come once the Arab citizens of Israel “accept that they will, with full equal rights, forever be a minority in the State of Israel.”

But not all his columns – which, by the way, he wrote daily, for decades – concerned hefty matters of state. In 1958, for example, Rosenblum happened upon a 13-year-old violin prodigy, one Itzhak Perlman, in a New York City hotel. Perlman’s mother had taken her polio-stricken son from Tel Aviv to the Big Apple, where she began working odd cleaning jobs, all in hopes of making her son into the next Jascha Heifetz. “This Jewess is nuts,” Rosenblum thought, and penned an acerbic column (entitled A Yiddishe Mameh) about the unreasonable lengths to which parents will go in order to push their children to excellence. Many years later, he admitted: “Well, OK, in my long career, this is one of the instances in which I’m glad I was wrong.”

He retired from Yedioth Ahronoth in 1986, and two years later lit one of the torches in the central ceremony celebrating Israel’s 40th birthday. He died in Tel Aviv in 1991, at the age of 87.

Here he is in 1961, speaking about Israel’s missed opportunity to become a regional superpower:

Herzl Vardi: Had we, 150 years ago, when along came Napoleon Bonaparte, and offered the Jews the opportunity to return to the Land of Israel and to build anew the Jewish kingdom, as he did in fact offer; had it then come to pass, that not only one Jew on the face of the earth, the rabbi of Jerusalem, who embraced Napoleon’s offer, had it been not just he alone who embraced the offer, but rather at least several thousand people, then, I think that today we would not be a small Jewish State in this part of the world, but rather a large empire, a very large empire, whose importance would be great not just in this area, but, perhaps, among the great global powers.

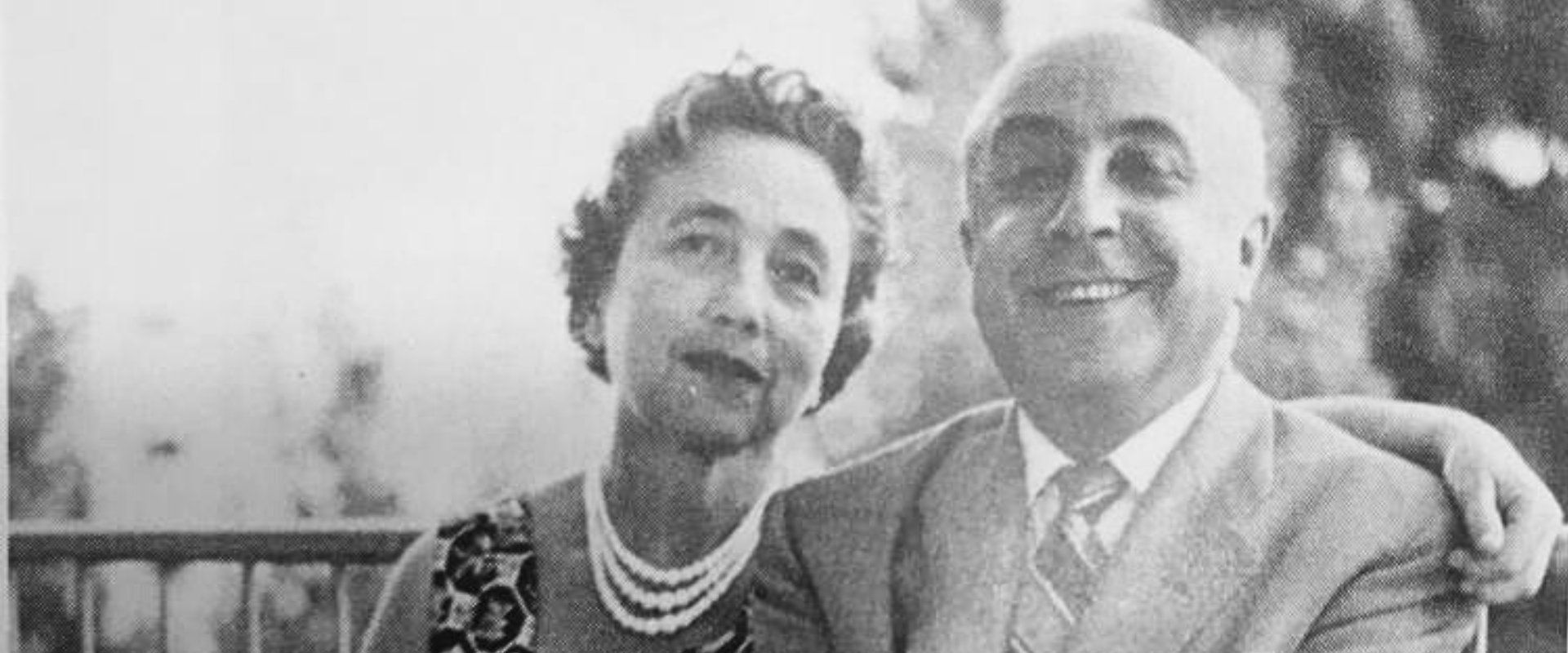

Doron Rosenblum: My name is Doron Rosenblum. I’m almost sixty-years-old. I was born in England, actually, and I came to Israel when I was three-years-old and since then I’m living in Israel. I’ve been working in the high-tech industry all my life, and Herzl Rosenblum, or Vardi, as his name appears in the Statement of Independence, was my grandfather. My grandfather and my grandmother were born in a town called Kaunas, in Lithuania. His father was an industrialist. He had factories where they manufactured all kinds of things. They were an established family, they had money. His father was already a Zionist, and he was raised into being a Zionist. My grandfather was called ‘Herzl’ to pay respect to Theodor Herzl. In Russian, there was no “heh,” there’s “geh,” so his family called him ‘Gerzl.’ He dealt with a lot of antisemitism, which later he told me, made him be more into studies, because Jewish people had to be better. Otherwise, they were just stepped on. One time, he said, “do you know that I speak Latin? And I speak Greek?” I said, “no, I didn’t know this.” And he started quoting by heart, Iliada and Odyssea in Greek. So I asked him, “why did you learn these poems by heart?” He said, “if I didn’t, I would have never been accepted to university. Jewish guys at the high school just needed to be better than others.” So here he was experiencing this strong hatred towards Jews. Basically, it was — the Jews need to support themselves. Nobody is going to help us. I think that the political view of my grandfather was shaped basically by his close work with Jabotinsky. He was the number two of Jabotinsky at the time. This was his political involvement. He decided to leave Lithuania after him and my grandmother, Lena, got married. So Jabotinsky offered him to join him at Vienna. In Vienna, he made his PhD in philosophy. Then they went to Paris, then to London, and they spent few years in each of those big cities. Jabotinsky told him, “now you need to be in Vienna,” he went to Vienna. “Now you need to be in London,” so he went to London. And then at the end they decided that they need not only to speak nicely about Zionism, but also to do the real thing. And at 1935, they decided to immigrate to Israel. So where he was working with Jabotinsky for many many years, and his childhood and how he grew up together it shaped his political view. Professionally, he was a journalist of a newspaper that was kind of the right-wing newspaper at the time. It was called HaBoker, ‘The Morning.’ It was the newspaper of the Revisionist Party. Thirteen years passed, and the Revisionist Party decided that he will represent them at the signature of the Declaration of Independence of Israel. The day of signing the Declaration of Independence was for him a day of huge excitement. He said two things: One, this was for him the most important moment of his life. And the second thing that he said was that he didn’t sign only for him. He signed it for many many of his family members that didn’t have the chance to be here when it was signed. He had four siblings – three brothers and a sister. All of them died in the Holocaust. For years, dozens of years, he was the Chief Editor of Yedioth Ahronoth, which is the largest newspaper in Israel. He was writing every day, an article – six days a week, every week, every month, every year for 30 or 40 years. He wrote thousands of articles about our lives here, about politics, about state’s affairs, about how we are with our neighbors, how we are internally, how we are with the states of the world. The only thing that he was interested in except of expressing his opinions was classical music. He was playing the violin for many many years. This is why I played the piano for many many years. He went to concerts, he had his own seat in the Heichal HaTarbut, the auditorium of culture in Tel Aviv, fifth row, dignified place. And for years, he was going to this concert hall, listening to music, meeting with the greatest musicians of the world, and sharing with us his love to classical music. Except of classical music, his main love was his grandchildren. As a teenage I was going to visit him and my grandmother every week. And I told them about the army, about my studies in the universities. He shared with me things from politics, from his youth, and so on. And then before I left, he always gave me — without my grandmother knowing about it — he gave me few notes, few shekels, and he said, “this is your pocket money. This is for you. Don’t tell anybody.” I think that my grandfather would have been really proud of what we achieved in these 75 years. I think that he would say that in some aspects, the vision was accomplished. We are here, we are independent, we are strong, nobody can kick us out of here. And any Jew in the world can come here and enjoy a comfortable life and a life in which he doesn’t need to be afraid of anybody and of anything. In spite of the fact that there are terror attacks, I think that there’s no fundamental threat to the being of the State of Israel. I think that there’s no fundamental threat to the being of the Jewish people. There’s no big question of, ‘are we going to survive as a people or not?’ The idea was materialized, we can close the book of what we try to achieve, it was achieved. The fact that my grandfather signed the Statement of Independence from one hand gives me a lot of pride. At the same times, it also creates a dilemma or a conflict for me. I see things that are happening these days in Israel and I feel very sad and disappointed and concerned about the future of this State, of the State of Israel. When I go back to the paragraph of the Declaration of Independence that reflects on the vision of the State of Israel, I read it and – unfortunately and sadly – I see things that are just not happening. Because they’re saying very concrete things about how all the citizens should have the same rights without distinction of their sex, their color, their race, their belief. I don’t think that this is how things are now. And I think that things are going to be even tougher in the future. And I think that they are far from what the people that signed the Statement of Independence meant. I think they’re far from the vision. I think that they’re not serving the original purposes on which this country was established, the original goals, the original principles, and I think that they pose a serious threat on our independence as a nation. And I see the long journey that my grandfather and other people started through the establishment of the State, and the wars, and all the great things that have been achieved and all the prices that were paid. And I see this journey that leads us to where we are now, and I’m sad, and I’m concerned. I am sure that my grandfather would have not defined himself as a part or a leader of what’s now called the right-wing. And actually if you take a close look at those parties that are calling themselves right-wing, it’s not really clear how and why they are portraying themselves as right-wing. This is for sure very far from what at the time was called right-wing. My wife’s name is Adoley. She’s from Ghana, and I got to meet her when I stayed in Ghana, in Africa, for few years. And we are a very, very unique family in the landscape of Tel Aviv. So when we go, all of us together – me, the three kids, Adoley, a beautiful, bald, black woman, people are looking at us and think ‘who is this unique, strange family?’ And this relates also to my grandfather. In spite of him being a right-wing statesman, he was very very open to other cultures, to people that are coming from different places in the world. He never perceived the Jewish race or the Jewish people as a superior one. It was always about paying a lot of respect to people from other colors, religions, cultures, and places and so on. And I’m sure that if he’d seen us now, as a family, speaking English at home with Adoley that comes from a different background, different culture, different religion, different color, I’m sure that he would have not only supported it, that he would have been very, very happy with us. I think that we are going now through an historical period. And I feel that this is a process that in a way is kind of irreversible. My wish is that my kids will make a choice to live here. They will not stay here because they don’t have a choice, because they are obliged to. And I hope that they will feel confident enough here, that they feel that Israel offers them opportunities, that they will feel that their children will be happy here, that they will have a good life in all aspects. That they will make a choice to live here. If this will happen, Israel is in a good state.

For a well-written, often hilarious, and non-chronological look at the chapters of Rosenblum’s life, see his exuberant autobiography, Drops from the Sea (Hebrew).

In 1961 Eliezer Whartman of the Israel State Archives conducted a series of interviews with 31 of the 37 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. For the full interview with Herzl Rosenblum, see here.

For a close look at his professional life, see this pair of articles from Maariv (Hebrew).

For an entry on his personal history, see the Encyclopedia of the Founders and Builders of Israel (Hebrew).

For a glimpse of Rosenblum’s fiery rhetoric (in this case on the matter of the reparations agreement with Germany), see this Ynet article.

For an in-depth (nearly two-hour-long) reflection on the various stations of his life, see this conversation between Rosenblum and Zev Golan.

For an insider’s account of Yedioth Ahronoth Managing Editor Dov Yudkovsky’s role under Rosenblum, see this account by Zev Galili.

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubber is Yoav Yefet.

The end song is Be’Toch Niyar Iton (lyrics – Kobi Oz, music – traditional Moroccan), performed by Teapacks.

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.