On June 29, 2007, Apple released its first iPhone. Less than sixteen years later, our world is an entirely altered place.

As more and more facets of our daily lives have migrated to the powerful little computers in our pockets, it is increasingly difficult to function without a smartphone. In fact, you’re probably reading these very lines on a phone.

We are naturally split when it comes to the matter of the desirability of this phenomenon. Ask most middle-schoolers and you’ll hear that a phone represents the promise of freedom, independence, fun and opportunity. Ask many screen-dazed adults and you’ll hear a completely different story – that the phone is a devilish device that has taken over our lives and shattered our ability to interact with each other.

But whether you love them or hate them; whether you are addicted or indifferent; whether you are excited by each new model or are still rocking a flip-phone – there’s no doubt that we live in the Pax Telefonica.

So in today’s episode, Hello Operator, we tell stories of first phones, but – well – not quite the ones Steve Jobs has bequeathed the world.

Yaron Blank and Shakked Ginsburg are both teenagers from Jerusalem. They attended the same elementary school, and their parents are friends. But that, more or less, is where the similarities end. Their main point of divergence? Phones, of course!

Shakked’s dad, Mitch Ginsburg – who himself attempted to get rid of that pinging rectangular device – tries to make sense of its appeal, or lack thereof. Now that his third child has begun angling for a phone of his own, Mitch is desperately looking for a way off the smartphone rollercoaster.

Act TranscriptMitch Ginsburg: Are you on Instagram?

Yaron Blank: No.

Mitch Ginsburg: Are you on Facebook?

Yaron Blank: No.

Mitch Ginsburg: Are you on Twitter?

Yaron Blank: No.

Mitch Ginsburg: Are you on any social media platform?

Yaron Blank: Ahhh…

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Yaron Blank, a blue-eyed and boyish tenth-grader from Jerusalem. He came to our brand new and amazing recording studio, Nomi Studios, in order to talk to our brand new and amazing producer, Mitch Ginsburg.

Mishy Harman: Hey Mitch!

Mitch Ginsburg: Hi Mishy!

Mishy Harman: How you doing?

Mitch Ginsburg: Great.

Mishy Harman: So Mitch, why did you want to talk to Yaron?

Mitch Ginsburg: Yaron? Well… because even though he’s about 35 years younger than I am, he is a bit of a role model for me.

Mishy Harman: A role model?

Mitch Ginsburg: In some ways, yeah.

Mishy Harman: In what ways?

Mitch Ginsburg: His phonelessness. I envy him for his phonelessness. [Mishy laughs].

Mishy Harman: Tell me more.

Mitch Ginsburg: Ummm… I tried it for a short amount of time. I think I was less successful than he has been, but there was a point in my life where I was desperate to be rid of my phone.

Mishy Harman: Ahhh… can you explain?

Mitch Ginsburg: I can. For several I was a military correspondent for The Times of Israel, and that meant many many many updates coming in through my phone. Middle of the night updates, terrible news updates, war breaking out updates. And I became very much addicted to the phone, and to those updates, so that I would have like… feel phantom vibrations and ringing and all sorts of things like that. And there was something about the nature of the updates, not just the constancy of the updates, but the actual nature of them, that was dreadful to me. In other words, it was frequent bad news that came in, and yet addictive as well. And so the phone, in many ways, symbolized that. Like, on the one hand, burst of adrenalin, and on the other hand sort of almost fear of what was coming or what might be waiting for me.

Mishy Harman: And you wanted out?

Mitch Ginsburg: I wanted out so badly.

Mishy Harman: So you decided to leave that job?

Mitch Ginsburg: Yup.

Mishy Harman: Because of the phone?

Mitch Ginsburg: To a large extent, I think, yeah. The phone is crucial part of the job. You have to know what’s happening. There’s a great emphasis on knowing what’s happening first, especially if it’s breaking news. Ummm… especially with this sort of like, army-based news. People want to know immediately. So I can remember one afternoon where, for the first time, a Syrian fighter jet crossed into Israeli airspace. If you find out about that ten minutes after everybody else, you’re not doing your job. And for me it was terrible. And I stopped. I… My last day on the job was the day that I also went to the phone company to give back that smartphone.

Mishy Harman: And how long did you last?

Mitch Ginsburg: I lasted, I think, about two years, something like that.

Mishy Harman: How was it?

Mitch Ginsburg: Well… I enjoyed being on the high horse a little bit, and telling people how free I was, not having a phone, not being distracted, not looking at it all the time. But I don’t know if people around me enjoyed it that much. I got lost all the time, I had to borrow my wife’s phone for her navigational device, for Waze, whenever I went anywhere. And people don’t like being asked directions these days because they just tell you to use your phone. So, yeah, there was a price to be paid.

Mishy Harman: And Mitch, you have four kids.

Mitch Ginsburg: Right.

Mishy Harman: And during this phoneless period, did they have phones?

Mitch Ginsburg: No. Not yet, none of them did. And I would often preach to them the wonders of not having a phone, and they were not a very receptive audience to this preaching. When my eldest daughter Shakked was in sixth grade, she basically spoke about nothing but phones. All of her friends had phones. I mean, everyone. Everyone in the class had a phone. And my wife and I, Tali, were holding out, but it was not an easy line to hold. I remember going to a parent-teacher conference that was meant to discuss phone usage among elementary school kids, and they were talking all about how to use WhatsApp, and the proper way to use it for a like a good online discourse, and how to use it at recess, and I was so frustrated that I just said “I would personally prefer if the principle were to like go around schoolyard and hand out lit cigarettes to the kids rather than have them use the phone during recess because at least that way they would like talk and interact with one another rather than huddle in the corner with their phone.”

Mishy Harman: [Mishy laughs] How did that go over?

Mitch Ginsburg: Not well. It was like silence.

Mishy Harman: And then, a few years ago and at least partially in a futile attempt to further delay the inevitable, you did something pretty unusual.

Mitch Ginsburg: Right. We packed up the whole family and we traveled through Italy by bike. Ummm… Three months, biking and camping. With the idea being no phones, no screen time. Sort of like a modern Little House on the Prairie, is what we had in mind. We’d all be together, Ma, Pa, the girls would go fetch water, everyone would get along great. Long, uninterrupted hours spent without phones. It didn’t exactly work out that way. Here’s Shakked, my daughter.

Shakked Ginsburg: I was like, ‘nooo.’ I knew this was a bad idea from the beginning and I was so right.

Mishy Harman: So… your phoneless odyssey backfired?

Mitch Ginsburg: Big time. [Mishy laughs] Entirely. I mean all of those nights that we spend in these churches, these quaint countryside churches? They only made her crave a phone even more. And as soon as we got back home to Jerusalem, she made it clear that the game was up.

Shakked Ginsburg: Then we came back and I was like, ‘oh, they’re getting me a phone. Like this is not gonna be a question anymore, I’m getting a phone. I went through misery, I went through hell, I will be getting a phone.’ And then they got me the crappiest phone on the planet. [Laughter]. But at least I had one.

Mishy Harman: And then what happened?

Mitch Ginsburg: Well, we got her a phone, and – as you can imagine – everything changed.

Mishy Harman: Like what?

Mitch Ginsburg: Like it became her best friend, and she was constantly on it. I had no idea what she was doing with it, and she would emerge from her room after hours, sometimes, of using it, and it seems to me at least that she was less happy than she had been before. And then the whole thing played itself out again with our second daughter, Gillie. And our third now, Matan, is constantly asking when he’s next in line. And I am desperately really looking for a way out. For some sort of creative way to curb my kids enthusiasm for this hellish device that they carry around in their pocket. So when I heard about Yaron…

Mitch Ginsburg: Are you on Instagram?

Yaron Blank: No.

Mitch Ginsburg: Are you on Facebook?

Yaron Blank: No.

Mitch Ginsburg: Are you on Twitter?

Yaron Blank: No.

Mitch Ginsburg: I thought he could teach me a thing or two.

Mishy Harman (narration): Alright, take it away.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Yaron Blank is a year older than my daughter Shakked. They went to the same elementary school, and I know his parents. He’s fifteen now, and not only does he not want a phone, he – get this – refuses to carry one.

Yaron Blank: Ah, so, well, like in the elementary school, there was a considerable amount of people that didn’t have phone or they had, like, a stupid phone or something like that. But then by seventh grade it’s like I was the only one without a phone.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Unlike us, Yaron’s parents didn’t even have to try that hard, let alone orchestrate a whole cycling trip through Italy.

Stacey Blank: There was a discussion with the teachers about the use of cellphones in school and my husband and I were not in favor of encouraging kids to use their phones.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Rabbi Stacey Blank, Yaron’s mother.

Stacey Blank: But it turned out pretty quickly that in seventh grade the teachers were very much in tune with the kids because all of the kids in the class had a cellphone, except for Yaron.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): As Yaron’s first year of junior high progressed, the pressure to get a phone started mounting. There were classroom assignments he wasn’t getting. Updates he kept missing. In-class competitions he couldn’t take part in. And, of course, a total shut out from any kind of social life.

But Yaron didn’t cave.

In fact, quite the opposite. Rather than conform, he bunkered down. He became the no-phone guy. That was his identity. His parents were thrilled.

Stacey Blank: At the time I was hearing stories from a friend whose son was in the same class, and that he… there was a WhatsApp group of the kids, and that it had no less than 200 messages a day. And some of the messages were hurtful to him and it seemed like a really unhealthy environment. So I was actually proud of Yaron that he could withstand peer pressure.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Then came COVID.

Stacey Blank: And very quickly, we began to see that the teachers found the easiest way to stay in touch with the kids and get information across was through WhatsApp. And in order to have WhatsApp, you needed to have a phone, and here began a bit of a struggle that for Yaron had become a matter of principle.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): We’ve all been there. Moments in which we have to balance principles and practicality. And Yaron’s genius solution? Outsource.

Stacey Blank: The teachers were putting me in the WhatsApp groups and I found myself very quickly becoming Yaron’s secretary, which obviously was not appropriate.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): So Stacy and her husband Tamir had their own moment of reckoning. A moment in which they had to choose between their educational ideals and, well… her life as a secretary. And their genius solution? Pass the buck right back to where it came from.

They sat Yaron down for a serious talk.

They discussed the importance of taking a stand, and the necessity, at times, of conforming.

Stacey Blank: It was not an easy discussion.

Yaron Blank: Yeah, it took a little convincing.

Stacey Blank: There were a few threats.

Mitch Ginsburg: What were the threats?

Stacey Blank: You won’t get to play chess. This is the young man we’re talking about.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): For Yaron, who recently won his school chess tournament, not being able to practice the Spanish Opening and the French Defense, was one step too far. Even his idealism had a limit, and that limit was the Queen’s Gambit.

And so Yaron reluctantly entered a new phase of life. The phone phase.

Yaron Blank: So, like, I use WhatsApp twice a day. In the morning and in the evening. And except for that I don’t use the phone.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): In some sort of modern-day Talmudic splitting of hairs, Yaron is still able to claim that he doesn’t actually have a mobile phone. And given the fact that the phone, an LG K42 in case you were wondering, lives in his bedroom drawer, I guess he’s right.

My slightly phone-obsessed daughter Shakked’s average daily screen time is around four hours. So I asked him what he does with all that extra time on his hands, other than chess, that is.

Yaron Blank: So, I don’t know, I read, I sit outside, like, or I meditate or something.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): Thinking about some of my own parenting choices, I went home and told Shakked all about Yaron.

Shakked Ginsburg: I think it’s absolutely insane, like, how do you do stuff, how do you talk with friends, how do you stay updated, like you need it to be able to be a social human being I think in this generation. We’re not a hundred years ago. You don’t go out and play in the mud. Like, it’s not what you do. Nobody does that. Like a board game? No. That’s just not what people do these days. [In Hebrew] There’s nothing to do about it.

Mishy Harman (narration): Hey, I’m Mishy Harman and this is Israel Story. Israel Story is brought to you by the Jerusalem Foundation and The Times of Israel. Our episode today, Hello Operator – stories of first phones.

When author Amos Oz was a little kid growing up in British Mandate Jerusalem, his parents didn’t have a phone. Instead, they’d ceremoniously march to the neighborhood “chemist” (as pharmacies were called back then), in order to place rare and expensive phone calls to far-away relatives.

The mechanics of these communications were a veritable source of wonder for the young Oz. In his mind, he recalled, he could “visualize a single line that connected Jerusalem and Tel Aviv and via Tel Aviv to the rest of the world.” Oz’ son-in-law, Prof. Eli Salzberger, brings us a hilarious and heartfelt extract from A Tale of Love and Darkness, all about the most anti-climactic phone call imaginable.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Now semi-phoneless Yaron is obviously an outlier. Much like Mitch’s kids, my little niece Shai Zena, who’s just eight-and-a-half, is counting the days till her Bat Mitzvah, which is when her parents told her they’d get her a phone. Almost all other phoneless kids I, and probably you, know, are similarly obsessed with getting a phone. To them, a phone represents freedom, opportunity, independence. To me and my nearly six hours of daily screen time, it represents imprisonment, servitude and well… basically death. But – hey – what do I know?

On our show today we have two stories of first phones, but of a very different kind than Yaron’s seldomly used android.

OK, Act One – It’s Good to Hear From You. My all-time favorite book is Amos Oz’ memoir, A Tale of Love and Darkness. If you don’t know it, or haven’t read it, I really can’t recommend it enough. It’s a story of growing up in Jerusalem, in the 40s and 50s, in what feels, and what was, a completely different world.

Now, as a huge and life-long Amos Oz fan, I read it as soon as it came out, in 2002. I was in the army then, and I can honestly say that its 593 pages shaped me into the person I am today. I’ve probably read it cover to cover six and seven times since then, and I’ve given it as a present to dozens and dozens of people.

There are many amazing moments in the book, which I think about often. But perhaps its most memorable scene, at least for me, is about a phone call. And about magical lines connecting the Kerem Avraham neighborhood pharmacy (in those days it was called a “chemist”) and the rest of the world.

Amos Oz died in 2018, so we asked his son-in-law, Prof. Eli Salzberger, to come in and record that scene. Here’s Eli.

Eli Salzberger (narration): Growing up, there was always a special magic hidden in the name “Tel Aviv.” As soon as I heard the word, I would conjure up in my mind’s eye a picture of a tough guy in a dark blue singlet, bronzed and broad-shouldered, a poet-worker-revolutionary, a guy made without fear, with a cap worn at a careless yet provocative angle on his curly hair, smoking Matusians. Someone who was at home in the world. All day long he worked hard on the land, with sand and mortar, in the evening he played the violin, at night he danced with girls or sang them soulful songs by the light of the full moon, and in the early hours he took a handgun or a sten out of its hiding place and stole away into the darkness to guard the houses and fields.

How far away Tel Aviv was! In my entire childhood years, I only visited it five or six times at most. Occasionally, we used to spend the chagim, the festivals, with the aunts, my mother’s sisters. It’s not just that the light in Tel Aviv was different from the light in Jerusalem. Even the laws of gravity were completely different. People walked differently in Tel Aviv. They leaped and floated, like Neil Armstrong on the moon.

In Jerusalem people always walked like mourners at a funeral or latecomers to a concert. First they put down the tip of their shoe and tested the ground. Then, once they had lowered their foot they were in no hurry to move it. We had waited for two thousand years to gain a foothold in Jerusalem, and we were now unwilling to give it up. If we picked up our foot someone else might come along and snatch our little strip of land. On the other hand, once you had lifted your foot, you wouldn’t be in such a hurry to put it down again. Who can tell what menacing nest of vipers you might step on?

For thousands of years we had paid with our blood for our impetuousness. Time and time again we had fallen into the hands of our enemies because we put our feet down without looking where we were putting them.

That, more or less, was the way people walked in Jerusalem. But Tel Aviv – wow! The whole city was one big grasshopper. The people leaped by, so did the houses, the streets, the squares, the sea breeze, the sand, the avenues, and even the clouds in the sky.

People in Jerusalem talked about Tel Aviv with envy and pride. With admiration. But almost confidentially, as though the city were some kind of secret project of the Jewish people that it was best not to talk about too much. After all, walls have ears, and spies and enemy agents could be lurking round every corner.

Tel Aviv. Sea. Light. Sand, scaffolding, kiosks on the avenues, a brand-new white Hebrew city, with simple lines, growing up among the citrus groves and the dunes. Not just a place that you buy a ticket for and travel to on an Egged bus, but a different continent altogether.

For years we had a regular arrangement for a telephonic dare with our family in Tel Aviv. We used to phone them every three or four months, even though we didn’t have a phone and neither did they. First of all we used to write to Auntie Hayya and Uncle Tsvi to let them know that on, say, the nineteenth of the month, which was a Wednesday, we’d call. See, on Wednesdays Tsvi left his work at the Health Clinic at three, so at five we would phone from our chemist to their chemist. The letter was sent well in advance, and then we waited for a reply. In their letter, Auntie Hayya and Uncle Tsvi assured us that Wednesday the nineteenth suited them perfectly, and they would be waiting at the chemist’s a little before five, and not to worry if we didn’t manage to phone on the dot of five, they wouldn’t run away.

I don’t remember whether we put on our best clothes for the expedition to the chemist’s for the phone call to Tel Aviv, but it wouldn’t surprise me if we did. It was a solemn undertaking. As early as the Sunday before, my father would say to my mother, “Fania, you haven’t forgotten that this is the week that we’re phoning Tel Aviv, right?” On Monday my mother would say, “Arieh, don’t be late home the day after tomorrow, don’t mess things up.” And on Tuesday they would both say to me, “Amos, just don’t surprise us, you hear? Just don’t be ill, you hear, don’t catch cold or fall over at least not until after tomorrow afternoon.” And that evening they would say to me, “go to sleep early, so you’ll be in good shape for the phone call, we don’t want you to sound as though you haven’t been eating properly.”

So they would build up the excitement. We lived on Amos Street, and the chemist’s shop was five minutes’ walk away, on Zephaniah Street. But still, by three o’clock my father would say to my mother: “Don’t start anything new now, so you won’t be in a rush.” “I’m perfectly OK,” she would answer, “but what about you with your books, you might forget all about it!” “Me?” he’d reply, “forget? I’m looking at the clock every few minutes. And besides, Amos will remind me.”

So there I was, just five or six years old, and already I had to assume a historic responsibility. I didn’t have a watch and so every few moments I ran to the kitchen to see what the clock said, and then I would announce, like the countdown to a spaceship launch: “twenty-five minutes to go, twenty minutes to go, fifteen to go, ten and a half to go…” And at that point we would get up, lock the front door carefully, and set off, the three of us, turn left as far as Mr. Auster’s grocery shop, then right onto Zechariah Street, left onto Malachi Street, right onto Zephaniah Street, and straight into the chemist’s where we’d announce: “Good afternoon to you Mr. Heinemann, how are you? We’ve come to phone.”

He knew perfectly well, of course, that on Wednesday we would be coming to phone our relatives in Tel Aviv, and he knew that Tsvi worked at the Health Clinic, and that Hayya had an important job in the League of Working Women, and that they were good friends of Golda Meyerson (who’d later become Golda Meir). And of Misha Kolodny, who was known as Moshe Kol over here. But still we’d remind him: “We’ve come to phone our relatives in Tel Aviv.” And Mr. Heinemann would say: “Yes, of course, please take a seat.” Then he would crack his usual telephone joke. “Once,” he’d say with excitement as if this was the first time he’d ever told it, “at the Zionist Congress in Zurich, terrible roaring sounds were suddenly heard from a side room. Berl Locker asked Harzfeld what was going on, and Harzfeld explained that it was Comrade Rubashov speaking to Ben-Gurion in Jerusalem. ‘Speaking to Jerusalem?’ exclaimed Berl Locker, ‘so why doesn’t he just use the telephone?’”

My father would say, “I’ll dial now.” And my mother would answer, “it’s too soon, Arieh. There’s still a few minutes to go.” He would reply, “yes, but they have to connect us” (because there was no direct dialing at that time). My mother, unconvinced by the reasoning, would retort, “yes, but what if for once we are put through right away, and they’re not there yet?” So my father would reply, “well, in that case we shall simply try again later.” And my mother, who had to have the last word, would decide, “no, they’ll worry, they’ll think they’ve missed us.”

While they were still arguing, it was almost five o’clock. Father picked up the receiver, and said to the operator: “Good afternoon, Madam. Would you please give me Tel Aviv 648.” Sometimes the operator would answer, “would you please wait a few minutes, Sir? the Postmaster is on the line.” Or Mr. Sitton. Or Mr. Nashashibi. And we felt quite nervous. Whatever would they think of us?

In my mind I could visualize a single line that connected Jerusalem and Tel Aviv and via Tel Aviv to the rest of the world. And if this one line was engaged, we were cut off from the world. The line made its way over wastelands and rocks, over hills and valleys, and I thought it was a great miracle. What if wild animals came in the night and bit through the line, I worried. Or if wicked Arabs cut it? Or if the rain got into it? Or there was a fire?

There was this line winding along, so vulnerable, unguarded, baking in the sun. I felt full of gratitude to the men who had put up this line, so brave-hearted, so dextrous. After all, it’s not so easy to put up a line from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv. I knew from experience. Once we ran a wire from my room to Eliyahu Friedmann’s room, only two houses and a garden away, and what a business it was, with the trees in the way, the neighbors, the shed, the wall, the steps, the bushes.

After waiting a while, my father decided that the Postmaster or Mr. Nashashibi must have finished talking by now, and so he picked up the receiver and once again said to the operator, “excuse me, Madam, I believe I asked to be put through to Tel Aviv 648.” She would say, “I’ve got it written down, Sir. Please wait patiently.” Father would say, “I’m waiting, Madam, naturally I’m waiting, but there are people waiting at the other end too.” This was his way of hinting to her politely that although we were indeed cultured people, there was a limit to our endurance. We were decent people, but we most definitely weren’t suckers. We were not to be led like sheep to the slaughter. That idea – that you could treat Jews any way you felt like – was over, once and for all.

Then all of a sudden the phone would ring and it was always such an exciting sound, such a magical moment.

The conversion went something like this:

“Hello Tsvi?”

“Speaking.”

“It’s Arieh here in Jerusalem.”

“Yes Arieh, hello, it’s Tsvi here, how are you?”

“Everything’s fine here. We’re speaking from the chemist’s.”

“So are we. What’s new?”

“Nothing new here. How about at your end, Tsvi? Tell us how it’s going.”

“Everything is OK. Nothing special to report. We’re all well!”

“No news is good news. There’s no news here either. We’re all fine. How about you?”

“We’re fine too.”

“That’s good. Now Fania wants to speak to you.”

And then the same thing all over again. “How are you? What’s new?” And then: “Now Amos wants to say a few words.”

And that was the whole conversation. What’s new? Good. Well. So let’s speak again soon. It’s good to hear from you. It’s good to hear from you too. We’ll write and set a time for the next call. We’ll talk. Yes. Definitely. Soon. See you soon. Look after yourselves. All the best. You too. Bye.

Mishy Harman (narration): Eli Salzberger. When he’s not acting out his late father-in-law’s childhood memories, Eli is a law professor at the University of Haifa, where he served – for many years – as the dean of the faculty.

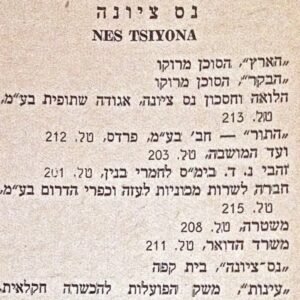

Tova Zahavi is both a scion of Nes Ziona aristocracy and a descendant of its most ridiculed outcast. In 1933, her grandfather – Natan David Zahavi – ventured where no Nes Ziona man had ever gone before: He managed to get his hands on the biggest attraction in town – a phone.

Ninety years later, his forgotten feat remains a source of both pride and fury for his nostalgic descendants.

Mishy Harman (narration): Our next story takes us from Amos Oz’ pharmacy in the Kerem Avraham neighborhood of Jerusalem to Nes Ziona, a town of roughly 50,000 residents nestled between Rishon Le’Zion and Rehovot. But Theo Canter’s story takes place in a very different Nes Ziona. Act Two – Press One For… Anyone. Here’s Theo.

Kid I: [Comes up] The hasback(?) test is basically a two-hour long test that is really hard, and I absolutely hate it.

Kid II: For me it was, ummm… social studies because there are like a bunch of people… [goes under].

Kid III: [Comes up] I hate when girls do that because…

Kid IV: It’s so annoying.

Kid III: [Comes up] We’re like, ‘oh, you’re no ugly.’

Kid V: So like my… my brother and my sister, they all went through the same school as me. And I had some teachers… [goes under].

Kid VI: And they’re like, ‘oh, people get in trouble for kissing in the halls’ and I’m like ‘jeez.’

Theo Canter (narration): In the spring of fourth grade, Zeke Bronfman became the first kid in my class to get an iPhone. We all watched in awe as he played Angry Birds, talked to Siri and took flashy selfies – feats that today, of course, seem pretty trivial. I didn’t get an iPhone until my Bar Mitzvah, and I felt majorly late to the game. For three long years I was jealous of the cool kids, flaunting their touchscreens and social media profiles while I was still making do with a stupid old flip phone. But this story isn’t about me. It’s about Tova, who – in a completely different time and place – was one of those “cool kids.”

Tova Zahavi: When other people later got phones and they were proud and talking about it, for me it was something very casual. Because it was something I got it from childhood. I was a baby when I saw it.

Theo Canter (narration): Tova Zahavi is, in a complicated way, both a scion of Nes Ziona aristocracy and a descendant of its most ridiculed outcast.

Tova Zahavi: I am the first granddaughter of Natan David Zahavi, who had the first phone in Nes Ziona in 1933.

Theo Canter (narration): Nineteen three three. That’s 1933.

Tova Zahavi: He had the first phone before the police.

Theo Canter (narration): That’s right. Before the Nes Ziona police had a phone line, Tova’s Saba Natan had one.

Tova Zahavi: We had a special number.

Theo Canter (narration): Two, zero, one. Of course someone had to be the first to get a phone, but Natan was an unlikely candidate. He wasn’t the mayor, the village doctor, or even… I don’t know, the local mohel. Instead – Tova told me – he was Nes Ziona’s quintessential outsider.

Tova Zahavi: Look, Nes Ziona was founded by ten families, who came from Russia and Poland in 1883. They were what we call the Mayflower.

Theo Canter (narration): But Natan? He most definitely was not one of the Mayflower folks. In fact, he arrived almost forty years later.

He was born in Kielce, Poland, in 1900, and came to British Mandate Palestine at the age of 22. Here he changed his name from the Polish ‘Zloto,’ meaning ‘gold’ to the Hebrew version, ‘Zahavi.’

Tova Zahavi: He came alone, first to Gedera, and went to work barefooted to Yaffo every day.

Theo Canter (narration): Natan jumped at whatever job was available, which back then was mainly paving roads and draining swamps. It was hard work, and soon he contracted malaria. The doctors recommended he go to a sanitarium in Switzerland to heal. Reluctantly, he started saving up and making arrangements to leave his new homeland. Right before he left, though, some friends invited him to a party of the Levinsky Seminar at Kolnoa Eden, Tel Aviv’s first cinema hall, in Neve Tzedek.

Geula Zahavi: And it was there, at that party, that he first saw Yael, a local Sabra girl, playing the accordion on the other end of the room. Natan had always loved music. From the day he was born, really. And he was enchanted by Yael and her magical melodies.

Theo Canter (narration): That’s an excerpt from a book called It Was Like A Dream, written by Tova’s aunt, Natan’s daughter, Geula, who passed away in 2021 at the age of 92.

Geula Zahavi: They began talking and he told her he was leaving for Europe, to recuperate. The very next day, Yael came by his apartment to sew up his jacket for the upcoming trip. One of Natan’s roommates started playing his mandolin, and they all joined in, singing and dancing. By the end of that evening, Natan already knew he wouldn’t be going to Switzerland. He decided then and there to overcome his malaria with the help of his new love, Yael.

Theo Canter (narration): So… he stayed, and eventually got better.

Before long, they got married and moved to Nes Ziona, Yael’s hometown. Theirs was sort of a Romeo and Juliet, or West Side Story, tale. They were, after all, from opposite sides of the tracks.

Tova Zahavi: It was a great love. Although her family didn’t want him.

Theo Canter (narration): See, Yael? She was a daughter of the Mayflower. Her parents, Shmuel and Sara Rofman, were local blue-bloods, and expected their daughter to marry someone… appropriate. Lovely and industrious as he was, Natan simply didn’t fit the bill.

Tova Zahavi: He wasn’t one of them. They wanted the new Jew, the land worker, and he was an immigrant. He was the typical old Jew from the diaspora. His intonation wasn’t the same Hebrew they talk. They patronized him, they mocked him.

Theo Canter (narration): From the very early days, Nes Ziona’s old guard – people like Yael’s family – worked the land. They cultivated orange groves, bred chickens, and – generally speaking – looked down on folks who made their living in trade and commerce. Natan, however, had neither the experience nor the desire to enter the citrus fields.

So, channeling his entrepreneurial spirit, he invested in something the town didn’t yet have – a hardware store. He sold wiring, paint, tools, things like that. It was perhaps less glorious and pioneering than working the land, but nevertheless – in a town still under construction – it was a necessity. And, indeed, things went well.

Geula Zahavi: He even used his commercial ties to bring us boxes of fresh fruit from Lebanon – juicy pears, crisp apples, and other fruits that you never saw here in those days. A good friend of mine once told me that she had asked her mother why we, the Zahavis, always had fruit on the table. And her mother told her, “it’s simple, Zahavi is rich!”

Theo Canter (narration): That’s… basically true. The store thrived and Natan was making a good living. But in 1933, he went one step further than procuring exotic fruit. He went where no Nes Ziona man had ever gone before. He managed to get his hands on the biggest attraction yet.

Tova Zahavi: I remember the phone, the black phone with numbers. I still hear the ringing!

Theo Canter (narration): The very first telephone in Nes Ziona, was in Natan’s store. At the time, the nearest hospital, the nearest fire department, even the nearest police station, were all still located in neighboring towns – Rehovot, Rishon Le’Zion, Ramle, Tel Aviv.

Tova Zahavi: In those days to go from Nes Ziona to Rishon Le’Zion is like going from Manhattan to Los Angeles.

Theo Canter (narration): So this phone was, in a very real way, the town’s only gateway to the outside world.

Tova Zahavi: Saba is asking me to hang off the phone because he has to speak to Tel Aviv. My father was always shouting to leave the phone, it’s a lot of money!

Theo Canter (narration): Though she was born more than fifteen years later, Tova still recalls the magic of that phone, which – even when she was a little girl in the 1950s – remained a novelty.

Tova Zahavi: It was a quite a attraction to have a phone, not only in Nes Ziona.

Theo Canter (narration): Tova would play with the phone, pick up the receiver, and wait – giddy with excitement – just to hear someone’s live voice on the other end of the line.

Tova Zahavi: You had to dial one, to get an outside line and you could speak to the world.

Theo Canter (narration): The phone turned Zahavi’s hardware store into the place to be. British soldiers would pop in to call home, musicians would show up to serenade those waiting in line for their turn, even the Jewish pre-state paramilitary groups understood the phone’s strategic importance and set up a secret weapons depot in the shop.

Tova Zahavi: Downstairs there was a slick of the Haganah, and I remember as little children they said, “you are not allowed to get there.”

Theo Canter (narration): Increasingly, people – not only from Nes Ziona, but from the entire region – came just to socialize, to witness this magical device.

And, true to himself, Natan cashed in on all the excitement.

Geula Zahavi: He somehow always got his hands on the newest inventions. It wasn’t just the first phone – we also had the first gramophone in town and dad would play his records so loud that the whole neighborhood could hear.

Tova Zahavi: They had the best cantors and records that were played in big noise and all Nes Ziona used to hear it.

Geula Zahavi: All these gadgets, all these innovative toys were really just a way for him to show the old-timers – and above all his wife’s parents – that he was just as good as them.

Tova Zahavi: In a way, there were things of showoff, yes, but it was part of him.

Theo Canter (narration): Unsurprisingly, this rubbed some folks the wrong way. The Mayflower clique, even his own in-laws, didn’t like the fact that Natan, of all people, was now the center of attention. The same Natan who had arrived decades after them, who didn’t play by their rules and who had made a fortune on his own. Many Nes Zionites were increasingly bitter and jealous.

Tova Zahavi: Silently in their rooms they were talking about how dare the outsider Zahavi to have phone.

Theo Canter (narration): There were awkward silences, angry glances, unpleasant encounters. And…

Tova Zahavi: One morning when he came to open his shop locks, he was terrified to find out that the locks were full of human feces.

Theo Canter (narration): The bluebloods had literally taken a dump on Natan’s door.

Tova Zahavi: And he took time to understand that it was an act of jealousy or envy by the so-called Mayflower citizens of Nes Ziona.

Theo Canter (narration): Natan realized that he may have overplayed his hand. He had flown too close to the sun.

The antagonism generated by his success was, ultimately, his downfall. His neighbors hated him, and made his life pretty miserable. They hoped he’d just give up and leave. But Natan wasn’t going anywhere.

So if they couldn’t drive him out of town, the old guard figured, they’d simply copy him. Private phones became the new rage.

Tova Zahavi: The police had the second phone, and then all the Mayflowers of Nes Ziona.

Theo Canter (narration): Once other people got their own phones, the hardware store reverted back to being, well… just a hardware store. A place where you get your screws, and paint, without all the mingling and live background music.

Slowly but surely the Mayflower elite dropped their Zahavi envy, or – at least this is what Tova thinks – found other things to be petty about.

Till today, a surprising number of Nes Ziona’s inhabitants – including the current mayor, Shmuel Boxer – are the descendants of those Mayflower families. But few – if any – know the story of Zahavi and his phone.

It is, however, detailed on a plaque, outside what used to be the hardware store – today it’s split between a law office and a bodega. Tova and her husband Doron took me there to see it.

Doron Zali: [In Hebrew] It was our store.

Tova Zahavi: [In Hebrew] Hello. This used to be my grandpa’s store. Zahavi. Can I go in with him over there?

Shopkeeper: [In Hebrew] Honestly, you can’t.

Tova Zahavi: [In Hebrew] You can’t let people in? [goes under].

Theo Canter (narration): “This was my grandpa’s shop,” Tova proudly told the teenaged cashier who couldn’t seem to care less.

Tova Zahavi: I remember as a little girl it was much much bigger. I was sitting next to the phone, my grandfather was sitting on his chair over there.

Theo Canter (narration): In the corner, where the phone once stood, there’s now a massive cooler full of XL energy drinks. Tova stared at it for a few seconds and then turned towards the door.

Tova Zahavi: You can imagine in 1933 in the middle of the desert, a beautiful house like this. All this place, you see upstairs, belonged to him. It was till here. Now it’s, it’s a store of what, of a little supermarket! Nothing!

Theo Canter (narration): It’s a cute story, really, to have had the first phone in a town. But on a deeper level, at least for Tova, it’s about more than that.

Tova Zahavi: It’s part of my soul. The phone was a symbol of a foreigner coming from Poland, rejected by the Mayflowers of Nes Ziona, coming over them. That’s all, that is story.

Theo Canter (narration): While the novelty of the first phone has long faded, alongside the very memory of it, the feelings it brought out still linger to this day.

Tova Zahavi: Look, I am 73 years old now. But I am still holding his inferiority feeling deep in my heart, and I am not willing to forgive.

Theo Canter (narration): Today, when we all have phones in our pockets that can reach much farther than the next town over, there’s something comforting, even humbling, about harkening back to a time when words weren’t cheap.

Tova Zahavi: Today, with all the smartphone, and the modern times, nothing impressed me as much as knowing that my family had the first phone ever in Nes Ziona.

Zev Levi scored and sound designed this episode with music from Blue Dot Sessions.

It was recorded at Nomi Studios and mixed by Adam Milliner. Becca Sykes read the passages from Geula Zahavi’s book, It Was Like A Dream. Episode artwork is “Pharmacists at the Shor Tabachnik Pharmacy on Allenby Street in Tel Aviv, c. 1939” (credit: Shor Tabachnik Pharmacies).