Almost immediately after the start of the attack of October 7th, as rockets were being launched at Jerusalem, and sirens sent the city’s one million residents into shelters, the heads of the Israel Museum initiated an emergency protocol for the first time since the Gulf War in 1991.

The idea was to protect the nation’s most priceless cultural and historical treasures, the building blocks of our collective identity. The very first step of that protocol was to secure the Museum’s most prized possession, its indisputable star, its “Mona Lisa” – the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Of all the estimated 500,000 treasured items in the Museum’s collections, from Monets to Picassos, from the Chalcolithic hoard of Nahal Mishmar to the House of David inscription from Tel Dan, it was the 2200-year-old scrolls that were packed up and rushed into the museum’s most protected safe. And it was Hagit Maoz, the Curator of the Shrine of the Book where the scrolls are normally housed, who was tasked with this delicate operation.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman: Like a lot of people play this game of like, well, if your house were on fire what would be the one thing that you would take? And the Israel Museum has answered very, very clearly. The one thing that we take is the one thing that you’re in charge of right.

Hagit Maoz: I live in a village that two-and-a-half years ago, almost was on fire. And the only thing I took from home, I mean, I told my kids, “now to the car,” and we took the cats, and I took the albums of my family.

Yes, I didn’t take anything, not underwear, nothing else. I took my family albums, and of course, my family. And we try to escape. And so it’s interesting what you’re saying now, because when you think what is dear to you is your history. And I did it. I mean it was clear to me that this is the most important, it’s the documentation about my ancestors so I have to take it with me. And I didn’t think about something else.

Mishy Harman: It seems like you and the Israel Museum think in the same way because in many ways these are the photo albums of our people.

Hagit Maoz: Absolutely, yes, you’re right.

Mishy Harman (narration): Hey listeners, it’s Mishy. So as you know, during these incredibly difficult days, we’re trying to bring you voices we’re hearing among and around us. These aren’t stories. They’re just quick conversations, or postcards really, that try to capture slivers of life right now.

Almost immediately after the start of the attack on the morning of October 7th as rockets were being launched at Jerusalem, and sirens sent the city’s million residents into shelters, the heads of the Israel Museum initiated an emergency protocol for the first time since the Gulf War in 1991. The idea was to protect the nation’s most priceless cultural and historical treasures, the building blocks of our collective identity. And the very first step of that protocol, securing the museum’s most prized possession: it’s indisputable star; its Mona Lisa—the Dead Sea Scrolls. Of all the estimated 500,000 treasured items in the museum’s collections, from Monets to Picassos, from the Chalcolithic hoard from Nahal Mishmar to the House of David inscription from Tel Dan. It was the 2200 year old scrolls that were packed up and rushed into the museum’s most protected safe. And it was Hagit Maoz, the curator of the Shrine of the Book, where the scrolls are normally housed who is tasked with this delicate operation. On a rainy day earlier this week, Yael Ben Horin and I fulfilled the fantasy of visiting a closed museum and went to talk to Hagit.

Mishy Harman: Can you introduce yourself?

Hagit Maoz: My name is Hagit Maoz. I’m an archaeologist, and I’m curator of the Dead Sea Scrolls at the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Mishy Harman: How many people come to visit the scrolls every year?

Hagit Maoz: About a million, about a million that comes each year, yeah, from all over the world. From everywhere you can think of: everybody. It’s amazing.

Mishy Harman: And can you tell me what happened on October 7th.

Hagit Maoz: So I was at home and we had at least five alarms and missiles that were falling around us. So I mean we were in shock. We didn’t understand what’s going on. And of course not in the morning. So at three o’clock I got a phone call from the chief curator of archaeology: he’s my boss. And he said: “We are now on a conversation with the board of directors and the director of the museum, and they all decided that the Dead Sea Scrolls are the most important objects, and please if you can come and take it to the safe room.” And I said: “Yeah, I need 10 minutes to prepare myself, and I’ll go.”

Mishy Harman: There was a fear that a missile could hit the museum and these objects would be destroyed. I mean, what prompted all of this?

Hagit Maoz: Yeah, I mean you can never know. You deal with enemy that you don’t know where he will attack. And we know that they were attacks towards the direction of Jerusalem. So you can’t risk, if you have any little doubt, there is no doubt that it should be in a protective place. You can’t take any risks. So I told my boys, I have two boys: “Listen, I have to go to the museum. And I don’t think it’s a good idea you’ll come with me because I don’t know what would have be now on my way. So if we have an alarm, you have to go into the safe room and stay there. And please call me.”

And so I left home. And on my way…the road was so quiet. It’s a scary quietness; it’s a scary emptiness. And when I came to the museum it was completely quiet, nobody is outside. And we are taking the scrolls very carefully. I mean, your brain tells you what to do, but your mind are in a different place. And my hands were a little bit shaking because it’s…I mean you can’t do it quickly.

So you open the showcase, you take off the frames carefully, and then you hold the scroll itself and go slowly as possible to the strong room. And it took us around two hours to take eight showcases…to open eight showcases, to take off the scrolls, put them in their position in the strong room. So when we finished—in one hand I felt relief because I know now that the manuscripts are well protected; on the other hand the situation was so different, I mean, okay, I did my job, it’s on a protective place, but I don’t know for how long, and I don’t know what will be tomorrow, and I don’t know what will be on my way back home. So everything was really different.

And you know, the manuscripts, of all the objects of the museum, they are symbols of the culture. And you know that when you are in that situation, the people who wants to kill you, or started the war, your symbols are a target for them, maybe to destroy them, as Daesh did. So we need to protect our symbols, or our a tradition, or I think in the case of the Dead Sea Scrolls is something that is a worldwide heritage, is not only us. So it’s a relief to know that they are in a safe place, so they won’t be damaged. I mean we always lie down on our history on our background, on our ancestors. And archaeology is us, is us in the past. So these manuscripts that were written two thousand years before our time, and more than that, are a reflection of thoughts, of understanding, of people who lived here. And these are their remains, and these are their heritage. So okay, of course at that time I… in Shabbat afternoon, I didn’t understand the scale of this horror that was still going on in the south. But the protection on your symbols of cultures, it’s part of you, it’s part of your identification. And that’s why it was so important to protect it.

Mishy Harman: And we’re six weeks into the war and they’re still in that safe.

Hagit Maoz: Yes, yes. And we don’t know for how long; it’s true.

Mishy Harman: Can we go into the Shrine of the Book to to see the empty showcases?

Hagit Maoz: Yeah, sure. We have to call the guard, of course, especially open it for you because it’s closed. But of course, I’ll do it. We will go to see the empty shrine in a minute.

[Sound of conversation in Hebrew]

We are at the Shrine of the Book in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. It’s the house of the seven first scrolls that found in the Judean Desert, in the northern part of the Judean Desert in a cave. And it is so sad to see it closed. And of course nobody can come, and nobody can visit. So we can hear only the raindrops from above.

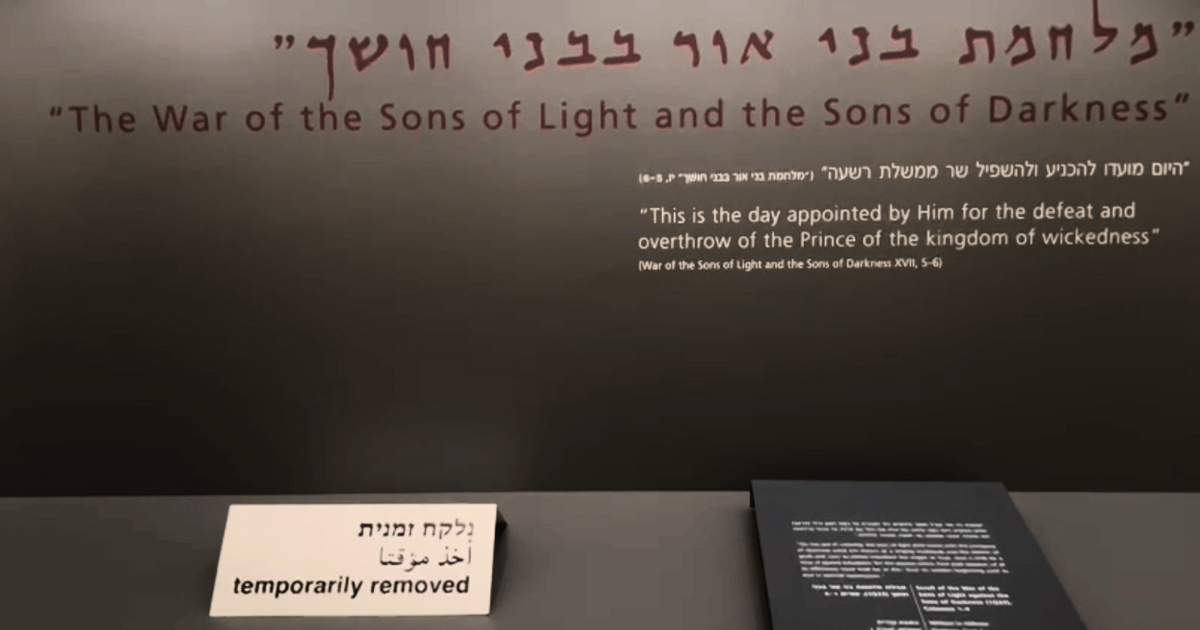

Mishy Harman: So Hagit, I see that the cases are completely empty, and their little signs that say that the artefacts have been taken away.

Hagit Maoz: Yes absolutely, it’s strange, it’s really not normal to see an empty gallery. An empty museum without objects it’s a hole in the heart, and it expressed for me the situation outside. And let’s hope it will change as quickly as possible. You know I left in each of the showcase…it’s a protocol to leave for the guards: “temporarily taken.”

Mishy Harman: Little signs, little pieces of paper.

Hagit Maoz: Pieces of paper that they will know that okay the showcase is empty not because someone stole the objects, but because it was taken to the safe room. So it strikes me suddenly that “temporarily taken” is not only of the objects, it’s something that also took me to the…crazy situation we are in that we have 237 people, souls—kids, women, men, elder people, that actually are not with us. And we miss these people. So “temporarily taken” is very sad and very hard but it has also a wish to the future to get them back.

The end song is Imperiot Noflot Le’at (“Empires Fall Slowly”) by Dan Toren and Hemi Rudner.