This is our final episode of the season, and it has been quite a journey. We began with our day at the Y, and have since explored all kinds of hidden corners of Israeli society: We’ve delved into the worlds of Israeli pork and Kosher Korean kimchi. We’ve excavated a 2000-year-old mikveh in Hanaton and nearly touched the surface of the moon with a blue-and-white rover. We’ve visited Shirley the turkey on the Freedom Farm in Olesh, entered chicken coups in Umm el-Fahm and searched for wild boars in Haifa. We’ve followed a season of women’s volleyball in Nazareth and the unlikely process of regrowing a foreskin. We’ve recorded at shatnez labs in Bnei Brak and date farms outside of Jericho, and – in our most recent episode – we told the heartbreaking tale of the 2001 suicide bombing at Sbarro.

We’re now heading into many months of production, during which we’ll research, record and produce stories for our next season, Season Seven. But as our way of saying goodbye to this season, we bring you four stories devoted entirely to things that are ending, going out of business or style, or coming to a close.

Every few years, once its warehouses of unclaimed lost-and-found items fill up, the Israeli police becomes Sotheby’s for a day. Back in November 2021, Adina Karpuj attended an unusual auction, but came home with none of the hundreds of “kosher” cell-phones, shtreimels, battery-less electric bikes or industrial ovens(!) that were up for grabs.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Every few years, once its warehouses of unclaimed lost-and-found items fill up, Mishteret Israel, the Israel Police, becomes Sotheby’s for a day.

Adina Karpuj: OK, so we’re here.

Mishy Harman (narration): Back in late November, our producer Adina Karpuj went to the Beit Dagan Police Station, near Rishon LeZion, to attend an unusual auction.

Mishy Harman: So Adina, what kind of items were being auctioned off there?

Adina Karpuj: So there were really all kinds of things. You know, lots of things that you would expect for people to have lost like phones, headphones, bicycles. You know there was a shtreimel, a bunch of strollers. But there were also really surprising things. There was an industrial oven, a refrigerator, remote controls for handling cranes and drones. You know, really surprising things that I don’t know how someone would lose that kind of stuff.

Mishy Harman: [Laughs] And who shows up to something like this?

Adina Karpuj: So I was really surprised about the kinds of people that come because really it spans the entire spectrum, as long as you’re male. So there were about a hundred and fifty men there. Me and the auctioneer and maybe a handful of cops were women, but other than that you had charedim, Arabs, young people, old people, rich people, poor people, techies, bikers, and there was this one guy, Dan.

Adina Karpuj: Hi, can I talk to you for a second?

Dan: Yeah, of course.

Adina Karpuj: What’s your name?

Dan: Dan.

Adina Karpuj: Hi Dan, nice to meet you. Can you tell me a little bit why you are here today?

Dan: Yes, I am here to buy an accordion.

Adina Karpuj: An accordion, wow. Are you an accordion player?

Dan: Yes, I am trying to be.

Adina Karpuj: You’re trying to be. So you are just learning now?

Dan: Yep.

Adina Karpuj: And how have you been practicing until now?

Dan: On the internet. Just learning stuff.

Adina Karpuj: So you have an accordion at home?

Dan: Yep.

Adina Karpuj: But you want another one?

Dan: Yes, and this one looks very very good. And I hope it will be in a good price.

Adina Karpuj: How much are you willing to put up for it?

Dan: I think two hundred, top.

Adina Karpuj: OK, good luck then!

Dan: Thank you!

Adina Karpuj: Hope to see you on YouTube one day.

Mishy Harman: And did he end up getting the accordion?

Adina Karpuj: So I found him at the end of the auction. Dan, what ended up happening with the accordion? Did you get it?

Dan: No, it was too high. They started at six hundred.

Adina Karpuj: Six hundred?!

Dan: Yeah.

Adina Karpuj: And you were coming here for two fifty!

Dan: Two-fifty tops. And in the end it has been sold for thousand shekels.

Adina Karpuj: Thousand shekel?

Dan: One thousand shekels! It’s OK, so no accordion for me, and hopefully I will get an accordion somewhere else. Maybe I will start my career as a accordionist YouTuber later…

Mishy Harman (narration): As you can probably hear in my voice, I’m a bit sick, but – don’t worry – it’s thankfully not COVID, just the flu. Anyway, this is our last episode of the season, and it’s been quite the journey. We began season six with our day at the Y, and have since explored all kinds of unusual and hidden corners of Israeli society. We’ve delved into the worlds of Israeli pork and Kosher Korean kimchi. We’ve excavated a 2000-year-old mikveh in Hanaton and nearly touched the surface of the moon with a blue-and-white rover. We’ve visited Shirley the turkey on the Freedom Farm in Olesh, Amir and his chicken coops in Umm el-Fahm and searched for wild boars in Haifa. We’ve followed a season of women’s volleyball in Nazareth and the unlikely process of regrowing a foreskin. We’ve recorded at shatnez labs in Bnei Brak and date farms outside of Jericho and – in our most recent episode – we told the heartbreaking tale of the 2001 suicide bombing at Sbarro. We’re now heading into many months of production, during which we’ll research, record and produce stories for our next season, Season Seven. But as our way of saying goodbye to this season, our episode today is called Going, Going, Gone, and is devoted entirely to things that are ending, going out of business or style, or coming to a close. Life – of course – is a series of some things ending and others things beginning. That’s the premise of every single bat mitzvah speech, every country music song, every Netflix rom-com. And we humans have decided to mark some of these changes in a formal way, with rites of passage. No matter who we are, where we live, or what religion we practice, there are events, ceremonies and rituals that accompany us from birth to death (and, in some cases, beyond). Many of these rites of passage are a source of much joy and anticipation – but some, like the one we’re going to hear about now, elicit – well – more ambivalent feelings.

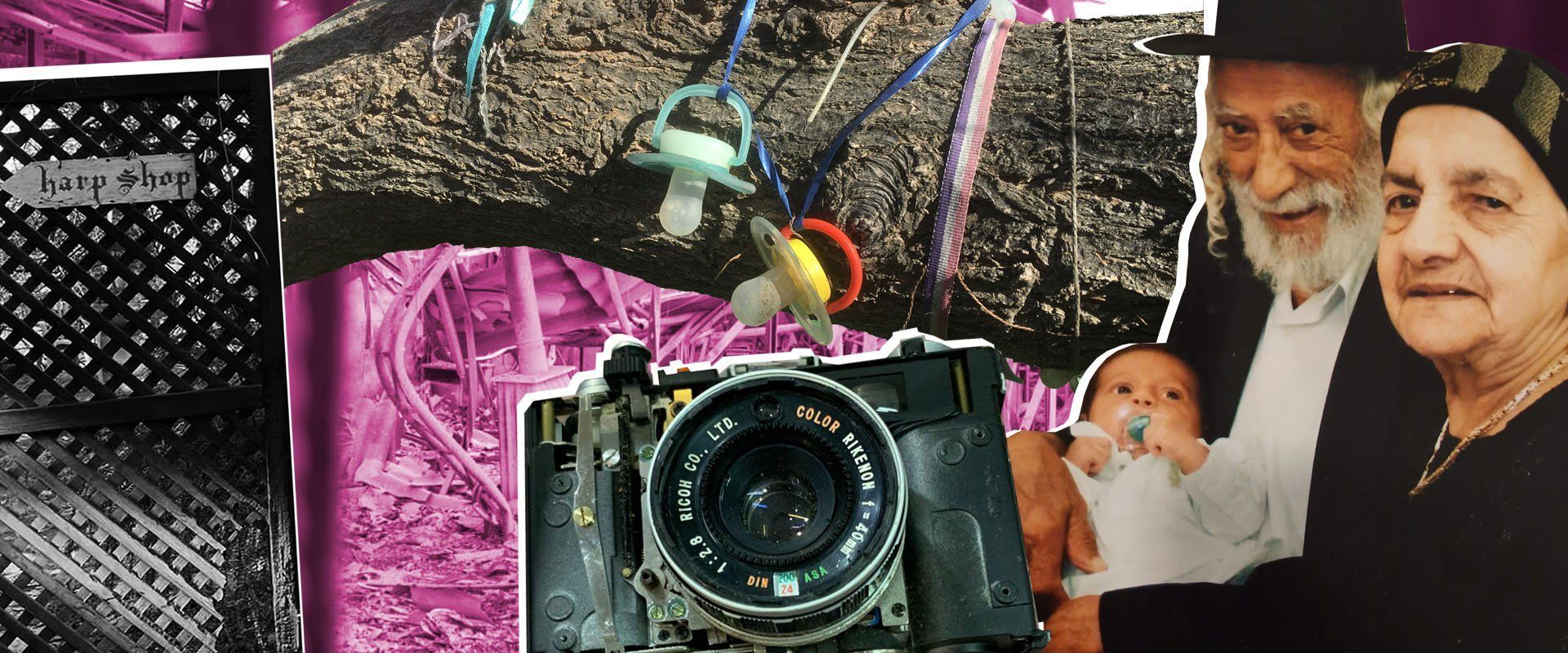

No matter who we are, where we live, or what religion we practice, there are ceremonies and rituals that accompany us from birth to death (and, in some cases, beyond). Many of these rites of passage are a source of much joy and anticipation, but some – such as the one Tanya Huyard observed at Jerusalem’s “pacifier tree” – elicit more ambivalent feelings.

Act TranscriptEliana: My name is Bellie. I’m… three.

Tanya Huyard (narration): I met Eliana, or “Bellie,” when I spent a Shabbat with her family in Jerusalem a few months ago. On her way to bed that evening, Bellie popped her pacifier – or “nunu” as she calls it – into her mouth as she bid me good night. It seemed to me that she was nowhere near ready to give it up. So I was surprised when – a few weeks later – her mom Liron invited me to join them for a trip to the neighborhood motzetz, or pacifier, tree. Now, if you have kids, or cousins, or grandkids, of the right age, you’re probably familiar with the concept. Pacifier trees originated in the ‘80s in the small village of Floda, near Gothenburg, in Sweden. Ulla Hjerling, the kindergarten teacher who came up with the idea, thought it would be a sensitive and respectful way to help toddlers part with their pacifiers and – at the same time – strengthen their connection to nature. I mean, if you hang your pacifier on a tree, it’s never really gone. You can still go visit, say hi and see how it’s doing. Pacifier, or dummy, trees quickly took off and spread across the world. And – like everything else, I guess – also made aliyah, in 2011. Today atzei motzetzim, as the blue-and-white version is called, grow in cities from Nahariya to Eilat, from Beit Shean to Ashkelon. In all those – and at least seventeen other municipalities – children (often accompanied by their parents and grandparents) come with pacifiers clenched tightly in their fists to say goodbye to a dear friend in a way that’s more meaningful than just throwing it away, or stuffing it in a random drawer. Sensing a radio piece in the making, I immediately told Liron that I’d be delighted to tag along. She warned me that it might not be as triumphant as I was imagining. See, she had already been through this ritual once before, with Bellie’s older brother, Daniel.

Daniel: I am five. I’m Daniel.

Tanya Huyard (narration): And given how things had gone with him, she wasn’t sure Bellie was actually ready to part with her nunu. So this was pitched as more of a dry run than the real thing. We’d all go, look at the nunu tree, get a sense of where the nunu would one day hang, and then come back home. When I showed up for this dress rehearsal, Bellie proudly showed me her two nunus.

Eliana: Look at it.

Tanya Huyard (narration): Judging by its wear and tear, it was clear which one was the favorite nunu. The one with the…

Eliana: Yellow and black ducks…

Tanya Huyard (narration): Yellow and black ducks.

Eliana: And Pink!

Tanya Huyard (narration): And – lest we forget – “pink!” As this excursion was really only meant to be a make-believe exercise, Bellie caught us all off guard when she looked up and asked…

Eliana: Can I put my motzetz on my nunu tree?

Liron: You want to put your motzetz on the motzetz tree?

Eliana: Yeah!

Liron: You do?

Eliana: Yeah. Right now. Today.

Tanya Huyard (narration): “Right now. Today.” This girl sure knew what she wanted.

Liron: What do we do at the motzetz tree?

Eliana: Um… We’re big kids. Not have any motzetz.

Liron: Not have any more motzetz afterwards?

Eliana: Uh huh! And then be a big kid!

Tanya Huyard (narration): As she squealed that – “and then be a big kid” – she looked up at her brother Daniel, who had much to say about the difference between a baby and a big kid, like himself.

Daniel: The thing is, a baby doesn’t know anything and a big kid knows more.

Tanya Huyard (narration): For instance?

Daniel: I know that cactuses don’t grow when there’s rain.

Tanya Huyard (narration): And…

Daniel: I know that metal is strong…

Tanya Huyard (narration): But when he was just a little kid?

Daniel: I thought metal was nothing.

Tanya Huyard (narration): With those important tidbits all sorted out, and – armed with puffy coats, warm mittens, and colorful rainboots – we were ready to set out into the Jerusalem winter and commence our farewell-to-nunu adventure.

Eliana: To the Nunu Tree!

Tanya Huyard (narration): To the Nunu Tree! A short bus ride up the hill and a pell-mell, tumble-bumble down the other side, we arrived at the Gonenim motzetz tree and all its germy glory.

Eliana: Nunu Tree!

Tanya Huyard (narration): Hundreds of nunus were dangling from the gnarled branches of the elm tree, shimmering in the golden glow of the streetlights. To me, at least, they looked like little votive offerings to the spirit of infanthood.

Eliana: Whoa, that is a lot!

Tanya Huyard (narration): Mesmerized by the sight of the fantastic tree, Bellie and Daniel began dashing from one nunu laden branch to the next. Then, Bellie got down to business.

Eliana: This one.

Tanya Huyard (narration): She carefully chose a branch, and – with Liron’s help – added her nunu to a long chain of other, older, nunus.

Liron: Bellie, you want to give it a kiss goodbye?

Eliana: [Eliana kisses the nunu]. Bye bye.

Liron: Do you love your nunu?

Eliana: Yeah.

Tanya Huyard (narration): A content smile instantly appeared on Bellie’s face.

Eliana: So happy now…

Tanya Huyard (narration): In fact, she was apparently so excited by the prospect of leaving her babyhood behind, that she decided that sending just one nunu into retirement simply wasn’t enough. She pulled out the other nunu from her pocket.

Eliana: Now I want to put it next to here.

Liron: We’re just gonna put one.

Tanya Huyard (narration): “We’re just gonna put one,” Liron said. Because as thrilled as Bellie was, her mom knew the night was still young.

Liron: Bellie, tonight are we going to sleep with a nunu or no nunu?

Eliana: No nunu!

Liron: Is it gonna be hard or easy?

Eliana: Easy peasy lemon squeezy.

Tanya Huyard (narration): Wanting to be supportive, but having experienced the legendary nunu withdrawal of her older child, Bellie’s mom pressed on.

Liron: What are you going to do to make yourself feel better? What do you think? A hug? A cuddle with your bear? What else?

Eliana: A nunu.

Tanya Huyard (narration): “A nunu,” Bellie answered. Thank god at least one nunu would be making the journey home.

Eliana: Bye Bye, nunu tree.

Tanya Huyard (narration): We walked back to the bus stop where, just an hour earlier, Bellie had been a little kid with two nunus. Deep in conversation with Daniel about life cycles and milestones, I made a rookie mistake and momentarily lost track of my protagonist, nearly missing radio gold. I turned just as her mom called out.

Liron: Hey! What’s in your mouth?

Tanya Huyard (narration): What was in her mouth? I rushed back to Bellie, who was dawdling behind us.

Tanya Huyard: Eli, what’s in your mouth?

Eliana: Nunu.

Tanya Huyard: Why is the nunu in your mouth?

Eliana: Because.

Tanya Huyard: Because why?

Eliana: Because it’s nighttime.

Tanya Huyard (narration): One pacifier away from being a full-fledged “big kid,” she popped her last remaining nunu back into her mouth, indicating that she was done talking. With this final tether to her “little-kid” status still in place, she held my hand tightly as we crossed the street together. Baby steps.

Mishy Harman (narration): Tanya Huyard. And now, from an end I imagine most of us went through (my mom says I was unwilling to part with my chuchu till I was almost four), to an end I very much hope no one listening has had to experience. On August 15, 2021 we were all at the Israel Story office, making last minute edits to our “Day at the Y” season opener. Suddenly we noticed a massive cloud of smoke appear outside the window. And that cloud of smoke? It didn’t really disappear for several days. This was one of the most catastrophic and extensive wildfires in Israel’s recent history. It consumed thousands of acres of trees and brush, and about two thousand people had to be evacuated from their homes. Ultimately, it took more than two hundred teams of firefighters, together with planes, helicopters, IDF and police forces and help from the Palestinian Authority to put out the flames. But of course, that’s when local residents – people like Micha and Shoshannah Harrari – realized all that was gone.

On the afternoon of August 15, 2021, the hills of Jerusalem were covered in smoke. It was, it would turn out after the fire was quelled five days later, one of the most devastating wildfires in Israel’s recent history. Roughly 14,000 dunams of forest had turned to ash, and so too had Micha and Shoshanna Harrari’s wooden harp workshop in Ramat Raziel. A month after the blaze, Elie Bleier went to meet them, and heard how this hippie couple plans to cope with their loss.

Act TranscriptShoshanna Harrari: When it starts snowing in Colorado, it can go on for a week.

Elie Bleier (narration): In the winter of 1979, Shoshanna and Micha Harrari found themselves up against a grand force of nature.

Shoshanna Harrari: We were out in the mountains in his little tiny wooden cabin with a dirt floor.

Elie Bleier (narration): To be honest, this kind of adventure was nothing new for the Harraris, a secular Jewish couple from the East Coast. They were, how should I put it… a bit out there. A bit less… conventional. Shoshanna was teaching herself to be a naturopathic healer, and Micha was a self-taught instrument maker.

Shoshanna Harrari: We were living very primitively, twenty-five miles outside of any civilization, completely and totally alone. It was wonderful. You wake up in the morning, the air is clean. You see the eagles flying and bears are walking by. And you’re like, ‘oh, wow, I’m in nature.’

Elie Bleier (narration): But this snowstorm – this was different, and it set their lives on an entirely new path.

Shoshanna Harrari: The first day it was really fun. I mean, we were like, ‘oh, this is like a movie, we’re snowed in.’ Because we really were. Fortunately, we had brought in some wood the night before. And I could push the one window open enough to get snow, so we could melt it and have water. So we weren’t gonna die. The second day, it was still fun, but not as much, hmm. The third day, it was very little fun. And by the fourth day, we had cabin fever and we wanted to get out of there.

Elie Bleier (narration): Since they couldn’t go anywhere, they passed the time reading.

Shoshanna Harrari: We had a few books that we had read already. So there was nothing else really to do. And the last book that we never read was the Tanakh.

Elie Bleier (narration): That is, the Hebrew Bible.

Shoshanna Harrari: I carried it around, I don’t even know why I carried it around. I never opened it, even the pages were stuck together. But on this particular day, this momentous day. It was the only thing we had not done. So we opened the book – “in the beginning.”

Elie Bleier (narration): At first, Shoshanna and Micha weren’t sure if they had actually found God, or if it was just a blizzard-induced trip. But as the snow melted away, it became clear to them that their newfound faith was just starting to heat up. They were drifters, sure. But they began contemplating a major change, even for them. Maybe, they thought, they should move to a magical land. A Land of Milk and Honey.

Shoshanna Harrari: We said, “oh, you know what, we’ll just get a donkey, and a cart, and we’ll travel around Israel till the Mashiah comes.” And that was our plan.

Elie Bleier (narration): There was only one small problem with this romantic idea…

Shoshanna Harrari: We knew nothing about Israel, except what was written in this book. We were all alone, and there was nobody – not a rabbi, not a leader, not even my mother – was there – to say, ‘that is not a smart idea.’

Elie Bleier (narration): With a few stops along the way – they were committed vagabonds, after all – they ultimately traded the Rockies’ wilderness for the Middle Eastern sun. But they quickly discovered that things weren’t quite as they had read in the Good Book.

Shoshanna Harrari: We were in complete culture shock. We didn’t speak Hebrew, we didn’t know what anybody’s saying, everything looked very strange, we had no idea.

Elie Bleier (narration): Instead of tents and camels, they encountered highways and towers. A far cry from the tales of Genesis.

Shoshanna Harrari: Avraham, Sarah, like, hey, they are our relatives, and they are so cool. They’re wandering and wandering around, living very primitively – like we were! It wasn’t like we were stupid or something. But we really didn’t think that this book was written a long time ago!

Elie Bleier (narration): But as they had already traveled halfway around the world, they decided to give the country a shot.

Shoshanna Harrari: So we don’t go see things as, like, tourists. We go somewhere, we live there.

Elie Bleier (narration): They eventually settled down in Tiberias, and breathed life into their biblical fantasy through Micha’s work.

Shoshanna Harrari: So we came across an archeological book that had a drawing called the ‘Megiddo harpist,’ and the archeologists date it to be three thousand years old.

Elie Bleier (narration): Micha had always promised to build Shoshanna a harp, and immediately said…

Shoshanna Harrari: “Yeah, that’s the harp we should make, a harp from Israel, a heart from our past, a harp from the time of King David.” By the rivers of Babylon. There’s a famous Psalm.

Elie Bleier (narration): So the couple decided to make that harp, and then another and another and another.

Shoshanna Harrari: The first twenty, they were not good instruments.

Elie Bleier (narration): But with time they improved and – before long – they became expert handmade harp makers, carefully crafting these ancient instruments in a modern land.

Shoshanna Harrari: The sweetest sound in the world is the harp. It’s so pure and so beautiful. It opens doors, opens the gates of heaven, it opens your heart. How did God even create this world? It says that he sang it into existence with the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet. The harp it has twenty-two strings. And the twenty-two strings correspond to the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alef-bet. So it’s a kind of mystical idea, that this world is a world of frequency. And the sounds that we produce are very important, because some sounds make us sick, and some sounds make us well. And the harp has always been known as an instrument of music therapy. Like you can read in the Bible. David was brought into play for Saul and Saul felt better, and the evil spirit left Saul. That’s very powerful. The harp really touches us.

Elie Bleier (narration): The Harraris ended up building a home and a harp workshop in Ramat Raziel, a small moshav in the forested hills of Jerusalem. And it was there, in that workshop, that wood and string were transformed into angelic instruments – ornate, exquisite, and much-desired pieces of art. In fact, for the last forty years or so, the Harraris’ harps have become world famous, and are shipped across the globe. Life, ultimately, was good to them. They were living peacefully, surrounded by trees, making harps and waiting for the mashiah to arrive. Until, that is, the afternoon of August 15th, 2021. More than four decades after that life-changing Colorado snowstorm, their lives were upended once again, this time by an opposite force of nature.

Shoshanna Harrari: We looked out the window and the sky was black. And there was a sound like a roaring ocean. And I’m like, hmmm… that is a fire!

Elie Bleier (narration): Micha ran out to the workshop, but…

Shoshanna Harrari: It was way too late. He couldn’t even get near it. The wind was blowing in our direction, he said, “we have to leave immediately,” and we just left with our clothes on our back. In something like that, you can’t think, you just have to act. I gotta just go because I’m gonna die If I don’t.

Elie Bleier (narration): It would take another five days till the flames were finally quelled. All in all, more than 14,000 dunams of forest had turned to ash. Ramat Raziel and several other nearby communities were evacuated, and locals didn’t know what remained of their homes. Micha and Shoshanna feared the worst.

Shoshanna Harrari: The next morning, we got a phone call from one of our neighbors. And they said, “your house is fine.” I was like “no, no, you must be talking about somebody else’s house. It’s not possible that our house is fine. It was twenty meters high flames blowing in that direction, about three or four meters from our wooden front door. How in the world could our house still stand?

Elie Bleier (narration): But when they finally returned…

Shoshanna Harrari: It was a miracle. I mean, honestly, there’s no other word for it. Because the house is wood. How could it not burn? But something stopped it. And nobody knows what that is. The only explanation is it’s the creator of the universe.

Elie Bleier (narration): The harp workshop, on the other hand, was…

Shoshanna Harrari: A catastrophe, a complete and total catastrophe. Every single thing that was in there was gone. What can you say in the face of that, you know? You just look at it. It’s like a power that you can’t really understand. There wasn’t like, we could rebuild from what we had. It’s like no, we have to start again from nothing. We were in shock, I mean really. It comes to me, like sometimes when I lay in bed at night, before I go to sleep. And you can’t process it for a while. There is a moment of hurt, like really deep hurt. And really when you see it, you see that a great, great tragedy happened here.

Elie Bleier (narration): The harps were gone, forty years worth of work. But somehow Shoshanna manages to maintain her optimism – and also her faith.

Shoshanna Harrari: Yes, it was a catastrophe. But what I really learned out of this is in order to have a new beginning, you really have to have a clear ending. Anyway, no matter what anyone wants to do, only God can do things like that. And that was his harp shop. And if he wanted to burn it down, he certainly had the right to do it.

Elie Bleier (narration): Shoshanna and I spoke hours before Yom Kippur began, exactly one month after the blaze. She stressed the importance of it being a shmita year – a year of Jewish renewal – when the land is given time to rest. Now, she said, they too would have to rest. And then, they’ll start all over again. As we said our goodbyes, she looked out the window, at the now decimated forest.

Shoshanna Harrari: The animals they ran, and the birds they flew, but the trees, they can’t go anywhere. So they had to stand there while this inferno of fire was coming at them. Yet they could dig their roots down deep and hold on to some source of life so they could make it and begin again. And I feel that we’re like that too. All of us. We went down there yesterday and we saw a little green shoot, and maybe in a few years it’ll be green again and you know, it’ll take time, maybe thirty years, but it’ll come back.

Elie Bleier (narration): It will come back. Amen.

Shoshanna Harrari: Great, well, may you be carried on the wings of angels.

Elie Bleier: Thank you.

Shoshanna Harrari: Yeah.

Mishy Harman (narration): At the very end of Allenby Street in Tel Aviv, right before the city spills into the Mediterranean Sea, there’s a little, hole-in-the-wall store called ‘Photo Doron.’ It’s a repair shop for film cameras – one of the last of its kind, like a fossil of a different era. The owner sits behind a big and cluttered desk. And perhaps surprisingly, isn’t called Doron.

Ya’akov Barzilai: My name is Jacob. Jacob Barzilai. And I repair camera.

Mishy Harman (narration): Jacob, or Ya’akov, has been fixing and selling analog cameras for more than half a century. He opened this shop, named for his son, in 1972. Obviously, technology has not made life easy for him. First he was nearly driven out of business by the digital camera, and now – of course – by the smartphone. But despite the fact that his profession may be closer to appearing in history books than in newspaper headlines, 79-year-old Ya’akov isn’t going anywhere.

Ya’akov Barzilai: I’m still here. Doesn’t matter about the money. Don’t think about the money.

Mishy Harman (narration): So why is that? And what is it about ‘Photo Doron’ that gives it the power to stick around long after most of its competitors have shut their doors?

At the very end of Allenby Street in Tel Aviv, right before the city spills into the Mediterranean Sea, there’s a hole-in-the-wall store called Photo Doron. It’s a repair shop for film cameras – one of the last of its kind, like a fossil of a different era. Skyler Inman stepped in and discovered why – though his profession is closer to appearing in history books than in newspaper headlines – 79-year-old Ya’akov Barzilai isn’t planning on going anywhere anytime soon.

Act TranscriptSkyler Inman: Hi, Jacob?

Ya’akov Barzilai: Hi, shalom.

Skyler Inman: Hello, how are you?

Ya’akov Barzilai: I’m OK…

Skyler Inman (narration): ‘Photo Doron’ is a tiny shop – or, at least, it feels that way. Wherever you look, there are floor-to-ceiling shelves packed with cords, lenses, tools, and – of course – cameras. I walk in carefully, doing my best not to accidentally topple the precarious piles of tripods and camera cases. To me, it seems like an unbelievable mess. But to Ya’akov? Everything is exactly where it should be.

Ya’akov Barzilai: I remember one day, my wife come here, she clean and put everything, you know? Then I can’t find nothing [laughter].

Skyler Inman (narration): Every morning, at 10am sharp, Ya’akov unlocks his shop and takes his place at a large wooden desk right in the middle of the store. On the wall behind him, there’s a tangle of antique cameras. He pulls one of them down and shows it to me.

Ya’akov Barzilai: 1903.

Skyler Inman: This camera?

Ya’akov Barzilai: This camera. This camera.

Skyler Inman: Was made in 1903?

Ya’akov Barzilai: It’s work. [shutter sound] Unbelievable.

Skyler Inman (narration): Entering ‘Photo Doron’ is like traveling back in time – not only because of what Ya’akov sells, but also because of who he is, and how he runs his business. In our glossy, branded, social-media savvy world, a shop like this feels like an endangered species. Ya’akov has no fancy website, no credit card machine, and other than a tall stack of business cards – no apparent advertising. He hardly even has a sign outside the door. In fact, as we sit and talk, people continuously pop their heads into the store out of pure disbelief. It’s like they’re saying, ‘this is still here? A film camera shop? What is this, 1983?!’

Ya’akov Barzilai: [In Hebrew] Hello. Oh, Hello!!! Hello!

Sasha Borodulin: How are you?

Ya’akov Barzilai: [In Hebrew] I’m OK, how are you?

Sasha Borodulin: OK.

Ya’akov Barzilai: [In Hebrew] Please.

Sasha Borodulin: I like very much that you are still here.

Ya’akov Barzilai: Thank you, thank you!

Skyler Inman (narration): The pleasantly surprised customer is Sasha Borodulin, an old-school Russian photographer with an… eclectic portfolio.

Sasha Borodulin: I am very diverse. I take pictures from the war to Playboy so… [laughs].

Skyler Inman (narration): Ya’akov is clearly excited to see Sasha.

Ya’akov Barzilai: Talking about three or four years I didn’t see him.

Skyler Inman: Wow.

Sasha Borodulin: We know each other for like twenty years.

Skyler Inman: You know each other for twenty years? Sasha Borodulin: Yeah.

Skyler Inman: That’s loyalty!

Sasha Borodulin: From one point of view, it’s loyalty. From another point of view, he’s the only one who is left.

Skyler Inman (narration): “The only one who is left.” Now, you might expect there to be something melancholy about a guy like Ya’akov, working all alone in a shop trying to sell something almost no one wants to buy. But Ya’akov is happy. Content. And… surprisingly busy. In fact, just as his old pal Sasha leaves, another customer walks in.

Ya’akov Barzilai: [In Hebrew] Hi, hello, yes, please…

Customer: [In Hebrew] Hi, I have a Sony video camera, one of those small ones…

Skyler Inman (narration): The guy’s looking for a cable for a specific Sony video camera. I think to myself ‘a digital camcorder? Ya’akov isn’t going to have that. He’s a film guy.’ But Ya’akov’s face lights up.

Customer: [In Hebrew] Should I bring it, or do you know what I’m talking about?

Ya’akov Barzilai: [In Hebrew] I know what you’re looking for. Here.

Skyler Inman (narration): He’s got it, he says, and reaches deep into one of the boxes right next to him. “It’s an original,” he tells the guy. “A hundred and fifty shekels, cash only.” The customer and I are both stunned – and impressed – by what just happened. He grins, hands Ya’akov the cash, and waves goodbye.

Ya’akov Barzilai: [In Hebrew] Thank you very much.

Customer: [In Hebrew] Bye, thank you very much!

Skyler Inman (narration): Ya’akov watches him leave, and, as soon as he’s out of earshot, turns to me and says…

Ya’akov Barzilai: See? I bought it for five shekel [Skyler laughs]. I sell it for a hundred and fifty. Three of those in day… that’s enough! Go home.

Skyler Inman (narration): That is, more or less, Ya’akov’s business model – accumulate stuff no one wants anymore, and then sell it, hopefully at a substantial mark-up, to a random person looking for something super specific. Most of the day, he just sits at his desk and waits, tinkering on this or that old camera until a customer comes in.

Ya’akov Barzilai: Change a little things here, there, put a new battery. That’s it. Three minute! I swear.

Skyler Inman (narration): But even though he makes it sound easy, Ya’akov really is good at fixing things. And by “things,” I don’t just mean cameras. Often, he tells me, clients come in with bigger problems than a broken shutter or a scratched lens.

Ya’akov Barzilai: Problem with the parents, problem with the wife. I’m good with how to manage things.

Skyler Inman (narration): Ya’akov pauses for a second, and seems to mull over his own statement.

Ya’akov Barzilai: Like a rabbi! [Laughter] HaRav Ya’akov… [Laughter].

Skyler Inman (narration): This clearly cracks him up. He’s an atheist, and a proud one, I gather, since he brings it up a bunch of times.

Ya’akov Barzilai: I’m not religious, I don’t care about that.

Skyler Inman (narration): Ya’akov and his family fled Iraq in 1951. They were part of a massive exodus of Iraqi Jews fleeing waves of antisemitic violence and intimidation following the creation of the State of Israel. So, if you ask Ya’akov, all religion seems to do is cause problems, divisions and violence. Things he’s got no time for. The family settled in Be’er Sheva, and when Ya’akov was eighteen, he was drafted into a special aircraft engineering unit where, in his words, he learned everything he needed to know about machines.

Ya’akov Barzilai: [In Hebrew] Hydraulics, electronics… [In English] everything!

Skyler Inman (narration): It was actually there, in the army, that Ya’akov got his first camera. Well… Sort of. See, it wasn’t his, per se. And, technically, it wasn’t just a camera.

Ya’akov Barzilai: It was a special aircraft with camera for spy.

Skyler Inman (narration): When Ya’akov finished his military service, and was done servicing spy planes, he knew he wanted to be his own boss. He also knew that cameras were all the rage. Looking around Tel Aviv’s beaches, parks and cafés, all he saw were people snapping pictures. Selling cameras would be a piece of cake, he thought. And when they’d inevitably break, he’d be able to fix them. He was, after all, a master repairman. So, Ya’akov saw an opportunity, and took it. He opened up his first photo shop…

Ya’akov Barzilai: Ibn Gvirol 1.

Skyler Inman (narration): And his second…

Ya’akov Barzilai: Ben Yehuda 84.

Skyler Inman (narration): And his third…

Ya’akov Barzilai: Yehuda HaLevi 51.

Skyler Inman (narration): Before long, he had a little photo empire.

Ya’akov Barzilai: Eh… Idelson 1… I had one in Petach Tikva…

Skyler Inman (narration): And, of course, this location: Allenby 16. Today, it’s the only one of his six stores that’s still in business. And that’s part of why he has so much stuff in here, he tells me: ‘Photo Doron’ is the last of last. A living museum of sorts. As we sit and chat, the trickle of customers slows down, and for a while, it’s just me and Ya’akov, alone in this world he’s inhabited every day for decades. And I find myself oddly comforted – by the unpretentiousness of the clutter, by the warm, cocoon-like feel of the tiny space. And most of all, just by knowing that a place like this exists. It’s not just my tendency towards the nostalgic, or my love of old cameras. It’s something more than that. To me, Ya’akov – and ‘Photo Doron’ – represent an alternative. Something different than our modern, high-speed, use-it, abuse-it, chuck-it-out-and-move-on society. At ‘Photo Doron,’ time moves slowly, old things are cherished and lovingly brought back to life, and efficiency – let alone showmanship – is not held in high regard. It’s the last night of Hanukkah, and it’s getting close to closing time. As Ya’akov gathers his stuff and gets ready to lock up, a gaggle of wide-eyed middle-schoolers walks by.

Ya’akov Barzilai: [In Hebrew] Hello girls, come in.

Skyler Inman (narration): They’re on school break, wandering around Tel Aviv. As they look around, it’s pretty clear they have no idea what this store is for. They just know it looks cool.

Girl: [In Hebrew] What is this store?

Ya’akov Barzilai: [In Hebrew] An old fashioned photography store…

Skyler Inman (narration): “It’s an old fashioned photography store,” Ya’akov explains.

Boy: [In Hebrew] What, you sell cameras?

Skyler Inman (narration): “You sell cameras?” they ask him. “Yes. Old cameras from way before you were born, I promise you that. And I fix them. Wanna see what they look like inside?” “Can I take a picture of this?” one of the kids asks as she instinctively whips out her iPhone. On one of the only patches of wall that isn’t completely covered with stuff, there’s a framed photograph of Ya’akov as a young businessman. In it, he’s wearing a skinny tie, his hair is thick, dark and curly. He is grinning, and proudly holding up a card that says Hertz Business Class. One of the kids notices it.

Boy: [In Hebrew] Is that you?

Skyler Inman (narration): “Is that you?” he asks with disbelief.

[Kids interactions with Jacob]

Skyler Inman (narration): “Look at you, you’re so handsome!” one of the boys chimes in flatteringly. Another of the kids asks if he could teach her about photography. Ya’akov, who is about to close shop for the day, tells her to come back any other day, four to six in the afternoon. He’ll be here. For a man of his age, Ya’akov seems to feel like he’s got plenty of time.

Skyler Inman: How much longer do you expect to be working here?

Ya’akov Barzilai: In my… ambition? All the time. Really.

Skyler Inman: No retirement for you?

Ya’akov Barzilai: No! I’m… next month, eighty. I was in a hospital. You know, sometime I don’t feel good. But it is something mechanic in body. I don’t have a big illness. No, I feel very young.

Skyler Inman (narration): Besides, he says, as he steps out the door, he’s still got a lot of stuff left to sell. A lot of cameras to repair. And until the doctors can no longer fix whatever mechanical problems his body might have, he intends to be right here, tinkering away at his desk.

Shlomo and Sarah Adani were married for longer than most people are alive. They grew up together in the small village of Dalah in Yemen, and were practically inseparable for more than eight decades. Renana Adani, their granddaughter, told Yoshi Fields about a partnership that began before the invention of color TV, atomic energy and super glue, and ended – in Jerusalem – within the span of 48 hours.

Act TranscriptRenana Adani: That’s her when she came to Israel. She’s wearing this black scarf around her head, and like a black dress. And she looks really young.

Yoshi Fields (narration): I’m in a small apartment in Jerusalem with thirty-six-year-old Renana Adani. We’re sitting in her living room and she’s showing me pictures of her recently deceased grandparents on her phone. There’s an old photo of the two of them sitting together on an auburn couch, proudly holding a chubby little baby Renana in their arms. In another, her grandfather Shlomo is blessing his wife, Sarah, his outstretched hands placed gently on her head. A scarf covers Sarah’s hair, and she has a mischievous twinkle in her eyes. Shlomo, on the other hand, is wearing the exact same thing in every single shot.

Yoshi Fields: He looks like a rabbi with a nice suit…

Renana Adani: Yeah.

Yoshi Fields: A hat.

Renana Adani: Yeah, always.

Yoshi Fields: Payot.

Renana Adani: Called simonim. The Yemenite call them simonim.

Yoshi Fields: Mmmm.

Renana Adani: Like the long payot.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Her grandparents were always a huge presence in her life. The two pillars of the large Adani family.

Renana Adani: We have a WhatsApp group of our cousins and he’s like the picture of our group. Like Saba’s watching.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Renana always looked up to them and saw their relationship as a model of sorts. I mean, after all, Sarah and Shlomo were married for longer than most people are alive.

Renana Adani: Yeah. Eighty-one years, almost eighty-two.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Eighty-one years.

Renana Adani: They had this thing of togetherness, of like… Their relationship is made out of two people but it’s really one thing.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Like many grandparents, especially those from a traditional background, Shlomo and Sarah wanted – more than anything – to see their granddaughter get married. It was no secret. In fact, it was the main topic of conversation whenever they’d talk.

Renana Adani: I remember him always asking me [in Hebrew] “what’s new?” Which is like, what’s new? So I said, at work I’m this, I’m that… and my friends, my… I don’t know… He said, [in Hebrew] “no, no, no, what’s new?” Like, “no, no, no, what’s really new?” Like he meant my like my love life.

Yoshi Fields (narration): But despite her grandparents’ desires, and her own – by the way – Renana had nothing to report. She hadn’t found her mate.

Renana Adani: I feel like the choice makes me look for something very specific. And yet, I can’t find that right now.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Saba Shlomo and Savta Sarah simply couldn’t understand why.

Renana Adani: They never had that choice. And I don’t think they even wanted that choice.

Yoshi Fields (narration): They were from a different generation, a different time and a different mentality. Their marriage predated color TV, atomic energy, the credit card and super glue, not to mention – of course – the State of Israel. They were both from Dalah, a small village in southern Yemen, and had practically grown up in the same house. Back in the 1930s, Sarah’s father had semi-adopted Shlomo, who had lost both his parents when he was just a child. A few years later, when Shlomo and Sarah were old enough to get married, he matched them. They had essentially been siblings, and then, all of a sudden, they were husband and wife. Whenever Renana asked them about this, they brushed it off with a smile.

Renana Adani: You couldn’t talk about these things. It was like… he was the best man for her, she was the best woman for him. These things were like straightforward. We got married, that’s it.

Yoshi Fields (narration): They were, Renana says, like a Yemenite version of Tevye and Golde, from Fiddler on the Roof.

Tevye: Do you love me?

Golde: I’m your wife!

Tevye: I know! But do you love me?

Golde: Do I love him?

Tevye: Well?

Renana Adani: Love wasn’t part of their vocabulary. I never heard them say the world, the word love. I never talked to them about love. I feel like I don’t even know if they know what it means.

Golde: Maybe, it’s indigestion.

Tevye: No, Golde, I’m asking you a question.

Renana Adani: I never saw them like looking into each other’s eyes or something like that. Or saying anything like soft. But all the things that they did for each other was like love for them.

Tevye: Then you love me?

Golde: I suppose I do.

Tevye: And I suppose I love you too.

Yoshi Fields (narration): They immigrated to Israel in the early years of the state, and raised a family – two sons and three daughters – in Rosh Ha’Ayin. Shlomo opened up a clothing shop and Sarah ran the house. But no matter what they did, they did it together.

Renana Adani: They didn’t even know themselves without each other. One unit.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Still, as Renana recalls, they were complete opposites. Saba Shlomo was a man of few words.

Renana Adani: Stop talking, let’s learn. That’s it. Always serious, with like a small, you know, small smile.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Savta Sarah, on the other hand…

Renana Adani: She loved to talk, she loved to tell stories. And she was very dramatic about everything and had all the details.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Growing up, Renana would curl up in a chair in their living room and listen to her grandmother for hours and hours. It was, she says, like a one woman Broadway production.

Renana Adani: Singing songs, and crying during the story, and laughing, and making jokes.

Yoshi Fields (narration): And while Savta Sarah didn’t know how to read or write…

Renana Adani: She really couldn’t read a clock.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Saba Shlomo was considered a very learned man and always had his nose in a Bible or a Gemara.

Renana Adani: People referred to him as Rabbi Shlomo.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Yet in recent years Renana watched as her grandparents’ bond seemed to outlast memory itself. In 2007, Sarah was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and – with time – she no longer recognized Renana and her other grandkids. Four years ago, she stopped talking altogether. But even from behind this growing veil of fog, she always seemed happiest, and most at ease, when she was beside her husband. Shlomo’s health was declining too.

Renana Adani: Just like being in the same room or knowing that the other one is fine, is doing alright. So these kind of things are like, they show me the very very strong connection that they had.

Yoshi Fields (narration): As Sarah continued to deteriorate, the family wondered – and worried – how Shlomo would cope once she inevitably passed away.

Renana Adani: Every time she went to the hospital we were like, thought it’s the e… like might be the end… should be, we were really tensed about it. And she always came back. My grandfather got like really excited and… about it and everything.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Then, Shlomo got cancer, and things moved pretty fast.

Renana Adani: In the past few months it was clear it was the end.

Yoshi Fields (narration): In the hours before he died, Renana and all of his children and twenty-six grandchildren came to see him. They sang prayers, and said their goodbyes.

Yoshi Fields: Do you remember what you said to him when you were saying goodbye?

Renana Adani: Umm… So I didn’t say it out loud. But I said it to my sister’s ear because I really wanted to say it but I wasn’t willing to share it with everyone but I said that I apologize that he never had the chance to be at my wedding to know my children. And is very hard for me because he was like, I knew he really wanted that for me. I felt like sorry for myself and wanted also to apologize to him.

Yoshi Fields (narration): A few minutes later, Shlomo died. He was a hundred and one.

Renana Adani: There’s something about it being so final that is like – you can’t change the situation. That’s what it is. And that’s what it’s ever going to be.

Yoshi Fields (narration): The entire family was gathered around him. Everyone that is, but Sarah, his wife. Given her dementia and fragile state, the family decided not to tell her that her companion of eighty plus years had died. But just a few hours later, as if she knew something was wrong, Sarah started having trouble breathing. As a precaution, they called an ambulance that took her to the hospital.

Renana Adani: She was fine. It was like another exacerbation and we were like, ‘ah we know that thing.’ So my aunt, which is a nurse, told me like “go visit her. I don’t trust anyone like I want you to look at the numbers and see how she’s doing.” So I came there and I was like “she’s doing better.” She started to eat. She’s on the right track. And then I was there for two hours and then suddenly she started deteriorating and five minutes she passed away.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Sarah was ninety-nine when she died.

Renana Adani: The idea that none of them stayed alone is very… it’s strong. I think maybe, maybe in a way she she felt, she felt that in some way that I can’t explain.

Yoshi Fields (narration): Together they had lived two centuries, and together they exited this world. Forever tethered.

Zev Levi scored and sound-designed the episode with music from Blue Dot Sessions, Shoshanna Harrari and Tamar Attias. Sela Waisblum created the mix. Thanks to Tomer Nissim, Aviv Weiss, Ehud “Oudoul” Cappon, Sheila Lambert, Erica Frederick, Jeff Feig and Joy Levitt. A special thanks to Dina Rabhan.

This is Israel Story’s final episode with Tablet Magazine. We will be announcing our new home in the upcoming months. But this is a time to say thank you Tablet, which has been our home since 2014. Our friends at Tablet believed in Israel Story when it was just an idea on paper, and together we have not only produced six full seasons but have also grown to become the most-listened-to Jewish podcast in the world. It has been an honor and a privilege to be part of the Tablet family, and to have had such an incredible model of first-rate journalism. Thanks to Morton Landowne, Alana Newhouse, Wayne Hoffman, Julie Subrin, Sara Ivri, Elissa Goldstein, Esther Werdiger, Kurt Hoffman, Mark Oppenheimer, Stephanie Butnick, Gabe Sanders and Josh Kross. We will miss you very much.

The end song, Yachol Lihiyot She’Ze Nigmar (“It Might Be Over”), was written by Yehonatan Geffen, composed by Shem Tov Levi and sung by Arik Einstein.