In the summer of 2005, the government of Israel unilaterally withdrew from Gaza. The roughly 8,000 residents of the 21 Jewish settlements within the Gaza Strip were forced to leave their homes and their communities, which – for decades – they had actually been encouraged and incentivized to inhabit.

The move brought the country to the brink of a civil war. This was especially palpable in the tense relations between the residents of Gush Katif (as the main block of Gaza settlements was known) and their neighbors from the other side of the fence — the largely left-leaning residents of the kibbutzim of Otef Azza, all the same kibbutzim that — eighteen years later — suffered most in the Hamas attack of October 7th.

Now, many of the former residents of the Gaza settlements who never stopped dreaming of returning to the sand dunes of the Strip feel at least partially vindicated. Had their communities not been dismantled back in 2005, they claim, the army would have still been in Gaza, and none of this calamity would have occurred.

63-year-old Datya Itzhaki used to live in the Gush Katif settlement of Kfar Yam.

Act TranscriptDatya Itzhaki: I said…if my leaving my home will even save one life of a Jew, I’ll go, but it won’t. And we said that time after time, and unfortunately nobody will listening. We were sure the situation in Gaza will be a lot worse. And we said it all along the time. If you’re going out, we’ll have here Hamastan.

Mishy Harman (narration): Hey, listeners, it’s Mishy. So as you know, during these incredibly difficult days, we’re trying to bring you voices we’re hearing among and around us. These aren’t stories, they’re just quick conversations, or postcards, really, that try to capture slivers of life right now.

In the summer of 2005, the government of Israel unilaterally withdrew from Gaza. The roughly 8000 residents of the 21 Jewish settlements within the Gaza Strip were forced to leave their homes and their communities—communities which for decades, the government did actually encourage and incentivize them to inhabit. The evacuation or disengagement, or expulsion—all depends on your political point of view—brought the country to the brink of a civil war. This was especially palpable in the tense relations between the residents of Gush Katif, as the main block of Gaza settlements was known, and their neighbors from the other side of the fence. The largely left leaning residents of the kibbutzim of Otef Aza, all the same kibbutzim that 18 years later suffered most in the Hamas attack of October 7th.

Now, former residents of the Gaza settlements, many of whom never stopped dreaming of returning to the sand dunes of the Strip, feel at least partially vindicated. Had their communities not been dismantled back in 2005, they claim, the army would have still been in Gaza and none of this calamity would have happened.

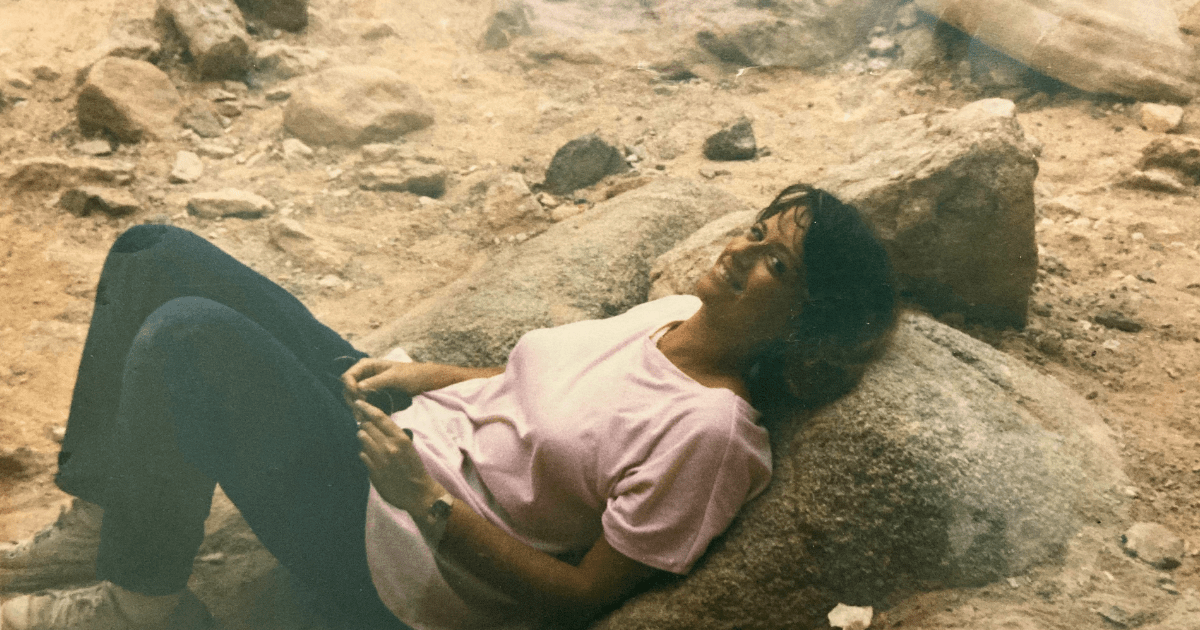

One such voice is that of 63-year-old Datya Itzhaki, who used to live in the Gush Katif settlement of Kfar Yam. Our producers Adina Karpuch and Mitch Ginsburg went to visit her in her still temporary trailer home on the beach just south of Atlit. You’ll also hear Datya’s husband Aryeh chiming in from time to time. Okay, here’s Datya.

Adina Karpuch: Can you explain to us a little bit about where we are?

Datya Itzhaki: So the way they evacuated people from Gaza, it was in communities. So we joined a community here. We’re the last group of Gush Katif that still has a problem: we didn’t build our permanent housing—so here there’s a camp of 16 families that live here already 12 years.

Mitch Ginsburg: They moved about…what 150 kilometers north along the same coast?

Datya Itzhaki: Same ocean, the same Arabs.

Mitch Ginsburg: Should we go inside?

Adina Karpuch: Can you start by introducing yourself.

Datya Itzhaki: Okay, my name is Datya Itzhaki, born in Kfar Haroeh. I got to Gush Katif in 1984: Kfar Yam—it was houses on the beach that already existed and in the beginning it was basically two families. And we didn’t have electricity. We had a generator, and they would basically put on the generator for the news. So between eight and nine in the evening we had electricity. We had water: sometimes not. It was what they call hityashvut bodedim.

I came there. I was single. And you know, they told me: “What are you coming to Gush Katif? It’s sand and sand and married sand. You will never find anybody here in Gush Katif.” And I was the spokesperson of the municipality, and I met my husband; he’s a tour guide. We met on the stairs of the municipality. I came down and he came up.

Really we felt completely free…grocery we did in Khan Yunis. I learned driving in Rafiach. My driving instructor, he was from Rafiach. That’s why I drive today like that, I have an excuse.

So it was a beautiful area, beautiful beaches, you know, swimming pool… and people came, they came for recreation to the Gaza region. You know, my family came to me when they wanted to have a nice weekend or something like that. All of that changed when the Intifada started. But still, you know, everybody saw it as their home. It wasn’t the thing that okay, you know, it’s dangerous, we get up and we go. It’s your home, so you’ll fight in it.

In the Second Intifada, there were 6000 bombs that fell on our communities: Neve Dekalim, Netzer Hazani was hit; Atzmona was hit. Six thousand—and at the time, also, we didn’t know how to deal with it. There was no mamad or shelter or thing like that, you know. So in Neve Dekalim, that’s bordered with Khan Yunis. Really, the line of Khan Yunis is the fence of Neve Dekalim. They got all the bombs on them. And like women will tell me that they have to decide at night what child to put underneath the steps because that’s the most safe. So every night they put another child there. It was very hard. But again, you know, it was our home, nobody thought of leaving. So there are a lot of miracles. We live from miracle to miracle.

Adina Karpuch: And there was never a moment where you said: is this worth it?

Datya Itzhaki: No. We felt that we are Zionists and we’re, you know, it’s like today soldiers are fighting in Gaza and they don’t ask: is it worth it? We felt like that. Yeah, it’s worth it if it’s your home. Arik Sharon, he was living very close, you know, the ranch Havat Shikmim is near Sderot. Many times problems in Nitzarim, you know, security things like that, the first one to be there was Arik Sharon: to come and help the people—really. And then he would go and said: “If Gush Katif wouldn’t have been here, we would have to establish it for the security of the State of Israel. Because the only way to control what’s happening in the Gaza region and from the border of Egypt is the civilians being here in Gush Katif”: Arik Sharon. I saw it in my eyes dozens of times. So we were there because Arik Sharon said it’s very important to be there. And then the same power that he had to help and to build, he had to destroy it.

Ariel Sharon: (in Hebrew) Members of Knesset, this is a fateful hour for Israel.

Female newscaster: The Israeli parliament approved the disengagement plan.

Ariel Sharon: (in Hebrew) For me this decision is unbearingly difficult.

Male newscaster: Israel had no intentions of staying in Gaza and was proceeding with a full withdrawal.

Ariel Sharon: (in Hebrew) I know the implications and impact of the Knesset’s decision on the lives of thousands of Israelis who have lived in the Gaza Strip for many years, who were sent there on behalf of the governments of Israel…

Male newscaster: The disengagement has begun. Thousands of IDF troops and police officers entered Gaza settlements this morning to hand out eviction notices to local residents.

Ariel Sharon: (in Hebrew) I am well aware of the fact that I sent them and took part in this enterprise, and many of these people are my personal friends.

Female newscaster: Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s unilateral plan of retreating from the Gaza Strip was in contrary to his statements before the elections. Gaza Strip settlers refuse to accept that they will be evacuated. They also refuse negotiating with the Israeli government.

Ariel Sharon: (in Hebrew) There is, in the Disengagement plan, a way to tear a hole into an alternative reality. With all the suffering involved, I am completely determined to complete this task.

Datya Itzhaki: That was a very, very bad feeling. That was betrayal because you don’t believe that your army is trying to…I don’t know, conquer your own house. And you’re evacuating citizens that were settled here by the government; you’re going against the values of settlement of the land; you’re going against values of security.

Adina Karpuch: It’s interesting. It seems like your ideology and your conviction never changed, it’s just that the public perception of it really changed.

Datya Itzhaki: Yeah, suddenly we weren’t already Zionist, we were an obstacle for peace. At the last day, we stood on the roof, and we had the children up on the roof and basically the army of Israel came to us on the land, on the sea, and in the air, for one house. And we still tried to convince them that what they’re doing is a mistake and it’s a crime against humanity, because it’s, you know, they’re uprooting people from their legal house. And in the end of the day the army of Israel succeeded.

So they took us on the bus and that was also something very, very hard. Because first of all we went out…we went through al-Mawasi—our Arab neighbors that were cheering that Israeli army is evacuating Jews. And then we went out of the Gaza region, and our neighbors from the kibbutzim were standing there and cheering because they’re taking us out of the Gaza region.

Aryeh Itzhaki: (in Hebrew) Be’eri, Re’im, Kissufim, Kfar Aza…the kibbutzim that were attacked.

Adina Karpuch: They were like standing on the street, on the side just cheering.

Mitch Ginsburg: Can you describe for us like some of your feelings on October 7th, having had, you know, sort of a tense relationship with them.

Datya Itzhaki: I think, first of all, it was a shock, like everybody else. Listen, it was a tense with these kibbutzim and for more than a year, they were standing every Friday in the junction with signs saying: “Come back home, leave Gaza.” And we have we have a video with me arguing with one of them, and this guy is now in Aza: kidnapped.

So we try to explain to them: We’re now, you know, your bumper; we’re there in order to make sure that you will be safe. Once we’re out, you have a big problem. And you know, they said: “You’re an obstacle to peace. We want peace with the Gaza region. We know them, you don’t.”

I know them. I lived there 21 years. Believe me, I know them. I know the good; I know the bad. And they paid the price. I feel very big sorrow, very big pain, double pain, because we knew how it could have been prevented. We said it will happen. And because of that it hurts so much. We said Hamastan. But the amount…the huge tragedy…nobody could think about it before. It’s a disaster…really.

Mitch Ginsburg: So what is the Gaza 2025 look like in your eyes?

Datya Itzhaki: So first of all, clean Gaza from terror. Second of all, take all the people out, the Arabs out of Gaza region and resettle them: put them in place of their own. Sinai is open, there’s a lot of place there. Take all the money of the world and I don’t care, you know, build them the most beautiful houses there is. And, third, build back the communities that are supposed to be there.

Mitch Ginsburg: You would be willing to move if the army and the government gave you the green light in a month, in 30 days, they said you can go back to no electricity on the beach, would you be up for it?

Datya Itzhaki: Arik?

Aryeh Itzhaki: (in Hebrew) Within an hour, I’m in Gaza.

Mitch Ginsburg: So you say in one hour you’re willing to…

Aryeh Itzhaki: One hour.

Mitch Ginsburg: Okay, and your wife?

Datya Itzhaki: Yes for sure. You know, home is a lot more than an apartment. Home is a place that gives you the feeling of security…of something else. And that only was in Kfar Yam.

The end song is Imma Im Hayiti (“Mom, If I Could”) by Hanan Ben Ari.