Daniel Auster was born in Galicia in 1893 and earned a law degree from the University of Vienna before making aliyah in the spring of 1914. He arrived just before the outbreak of World War I and was, indeed, soon drafted into the Austrian army, serving as an officer in the Damascus headquarters of Djemal Pasha, the region’s Governor and Military Commander.

After the war, Auster settled in Jerusalem, married Julia Mani, the daughter of the Hebron-born justice Malkiel Mani, and opened a law practice. He was, according to the 1921 local phonebook, one of just seven practicing lawyers in town.

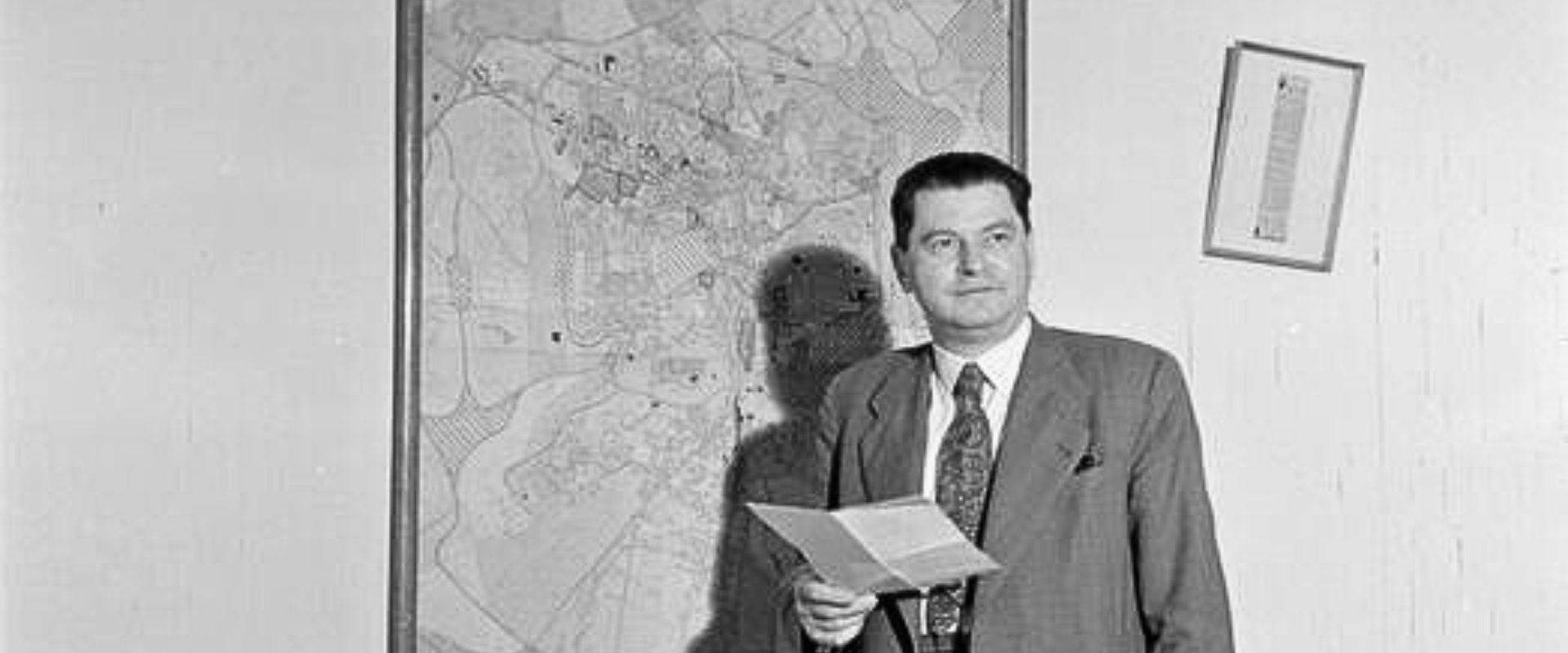

He was civically active – helped found the neighborhood of Rehavia, and served on the city council, as Deputy Mayor and then – amid endless drama and maneuvering between the city’s Jewish, Muslim and Christian politicians – as Acting Mayor. He was officially appointed to the city’s top job by the British High Commissioner in the summer of 1944 after the death of Mustafa al-Khaldi.

He was a member of the Zionim HaKlali’im, the General Zionists, a centrist political party that supported Chaim Weizmann, rather than Ben-Gurion, and that is today considered to be one of the ideological ancestors of the Likud party.

He unsuccessfully ran for the first Knesset on an independent list called ‘For Jerusalem,’ receiving a grand total of 842 votes nationwide. Humiliated, he continued to serve as Mayor of the new state’s capital till 1951.

For the rest of his life – till his death in 1963, at the age of 69 – he worked as a lawyer, and also, somewhat randomly, as Thailand’s honorary Consul General in Israel.

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: there were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

Today we’ll meet Daniel Auster, and his nephew, Eli Racah. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Act TranscriptEli Racah: My uncle was the Mayor of Jerusalem during the British Mandate. During the last day before they leave, there was a lot of fighting and bombing and during this last night he heard banging on the door and he was afraid. And he asked, “who is it?” “British Army!” He thought maybe they came to arrest him. So he opens the door in pajama, and there was a British Corporal and two soldiers with tommy guns pointed toward him. The Corporal said, “are you Daniel Auster?” He said, “yes.” “His Highness the High Commissioner appointed you an officer of the British Empire. Here it is, Sir. Back face forward march.” And they left him like this in his pajama.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Eli Racah, the nephew of Daniel Auster, the first Jew to be appointed Mayor of Jerusalem since Byzantine times. Interestingly, while Tel Aviv does make an appearance in the text of the Declaration of Independence, Jerusalem – the supposedly eternal capital of the Jewish people – does not. Want to know why? Listen on.

[Signed, Sealed, Delivered? introduction]

Today we’ll meet Daniel Auster, and his nephew, Eli Racah. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series. Here’s our producer, Lev Cohen, with Eli Racah, Daniel Auster’s nephew.

Lev Cohen (narration): Daniel Auster was born in Galicia in 1893 and earned a law degree from the University of Vienna before making aliyah in the spring of 1914. He arrived just before the outbreak of World War I and was, indeed, soon drafted into the Austrian army, serving as an officer in the Damascus headquarters of Djemal Pasha, the region’s Governor and Military Commander.

After the war, Auster settled in Jerusalem, married Julia Mani, the daughter of the Hebron-born justice Malkiel Mani, and opened a law practice. He was, according to the 1921 local phonebook, one of just seven practicing lawyers in town.

He was civically active – helped found the neighborhood of Rehavia, and served on the city council, as Deputy Mayor and then – amid endless drama and maneuvering between the city’s Jewish, Muslim and Christian politicians – as Acting Mayor. He was officially appointed to the city’s top job by the British High Commissioner in the summer of 1944 after the death of Mustafa al-Khaldi.

He was a member of the Zionim HaKlali’im, the General Zionists, a centrist political party that supported Chaim Weizmann, rather than Ben-Gurion, and that is today considered to be one of the ideological ancestors of the Likud party.

For a while he believed that the placement of his signature on the Declaration of Independence, just below that of Ben-Gurion, was a virtue of his position as Mayor of what poet Yehuda Amichai once called, quote, “the port city on the shores of eternity.” Instead, it was due to his last name starting with the letter aleph, or A, as everyone after Ben-Gurion signed in alphabetical order.

He unsuccessfully ran for the first Knesset on an independent list called ‘For Jerusalem,’ receiving a grand total of 842 votes nationwide. Humiliated, he continued to serve as Mayor of the new State’s capital till 1951.

For the rest of his life – till his death in 1963, at the age of 69 – he worked as a lawyer, and also, somewhat randomly, as Thailand’s honorary Consul General in Israel.

Here he is recalling the not-so-pleasant conversation he had with the Prime Minister after signing – or, as Ben-Gurion saw it, scribbling a mess – at the bottom of the Declaration of Independence.

Daniel Auster: I signed with my usual signature, which David Ben-Gurion, well… didn’t like. He said, “what is this, Auster, do you know what it is you’re signing here?!” I said, “I know exactly what I’m signing and I know it’s an historic document that will remain for generations upon generations, but what can I do? This is my signature. And if I sign in some other manner, it simply won’t be my signature.” He said, “but your signature is entirely illegible.” I said, “I know. I’m very sorry but as a function of having served as the Mayor of the city for so long, I had to ruin my signature given the vast number of signatures I had to sign every day. But that is my signature. I have no other.”

Eli Racah: I am Eli Racah. I live here in Tel Aviv. I am the nephew of Daniel Auster. There are no living children of his today. His son Eli (we are all called Eliyahu because of my grandfather who was Rabbi of Hebron — Rabbi Eliyahu Mani), Eli – Daniel Auster’s son – he was about 16-year-old and he played with the gun of Daniel Auster bodyguard, and the gun fired and he was killed by it. I am the first kin of him. He came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to Jerusalem in 1914 during the Ottoman period. When the First World War erupted in August 1914, he was drafted to the Austrian army in Jerusalem and he was sent to Damascus and he served there as an Austrian officer. During 1917 when there was the Balfour Declaration, Zionism movement became allied with Great Britain, the enemy of the axis. Zionism was banned. There was an underground called ‘Nili’ that spied for the British in Palestine. Two of them — Belkind and Lishanski — were caught and brought to Damascus and hanged there, and he saw it from the window of his office. And he was very afraid, because before the War, he worked for Arthur Rupin, the financier of the Zionist Movement. They had a trick. In Palestine, the gold coin was worth four ordinary coins, and in Istanbul, the gold coin was worth five. So they bought gold coins in Palestine and Daniel Auster was sent to Istanbul to change them for simple coins. And that’s how they made a lot of money for the Zionist Movement. He had a friend who was a journalist. And he told him the story but he told him, “don’t publish it. If you publish it, I will be in trouble.” So when he was in the headquarter and saw the two Nili people hanged, he also received newspapers from Palestine. And there he saw his story! And he said, “now they are going to hang me!” Luckily, the Turkish generals didn’t read it. But he was very afraid. When he came back to Jerusalem, he said, “why did you publish it? You promised not to publish it.” He said, “yes, I wasn’t in the office, and some other journalist find it in my drawers. And he published it, I’m so sorry.” During the ‘30s, the Jews were the majority in Jerusalem. So he was elected Mayor, but the British High Commissioner told the Jewish Agency that they cannot appoint a Jew as a Mayor of Jerusalem because the Arabs will rise. The Jewish Agency agreed with the British that an Arab will be appointed as a Mayor, but it will be an Arab that the Jews will choose. They chose an Arab called Khaldi. My uncle was a Vice Mayor. And when my parents got married, my parents are photographed with Daniel Auster and with the Arab Mayor of Jerusalem Khalidi. My uncle was a very conservative man, always photographed with all the frocks and hats and ties and the whole set. And he was very strict with what should be done and what shouldn’t be done. He was not the uncle to play with. He was a very distinguished person. We liked to hear his views about the politics of this time. Jerusalem was always a multicultural place – Jews and Arabs and Haredis and secular people, and he was used to it. I mean, he had good relations with Haredi politicians. But he was very secular. He would have been annoyed by the fact that in his neighborhood, Rehavia, and he was one of the founders of Rehavia, there are so many Haredi Jews today. It’s not a surprise that Jerusalem is not part of the Declaration. Ben-Gurion didn’t mention Jerusalem because he knew that it will make a lot of antagonism. According to the UN resolution making the Jewish State and an Arab State, Jerusalem was to be an international city. And he knew that if he will put Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Israel, it will make a lot of antagonism in the world. Of course, it give me a lot of pride that he was one of the signatories. The Declaration of Independence is very important. And even today, when we fight against ideas of abolishing the judicial system, we base our claims on this Declaration of Independence. And of course he understood it and he approved of it. Although it’s a Declaration of Independence of the Jewish State, it also a declaration of human and minority’s rights. My uncle died in 1963. Jerusalem changed very much during the years. When I grew in Jerusalem, it was a very small city. The Jewish part of Jerusalem separated from the eastern part that was Jordanian. We didn’t talk about Palestinians but about Jordan. That’s the city I knew. And then after the Six Days War, Jerusalem changed very much. And the whole unification, I don’t think it brought Jerusalem to good things. Of course as the first Mayor of Jerusalem, if he could live in the time of 1967, when the city was reunited, my uncle would have been very glad about it. All of us were thrilled. There were only one or two or three people who warned us like the prophet Jeremiah, you know? Warned from the catastrophe. Now we’re seeing that they were right. But in those times, none of us saw it. Waking up from the dream took some years later. The unification in 1967 was bad because it gave, let’s say the more religious all kinds of, we call them, ‘Messiah ideas’ — that the Messiah is coming and it’s our role to make the whole country Jewish and to expel the Arabs and so on. They became more and more important in the politics of the State of Israel. That’s why I’m for the two state solution. I don’t think that Jerusalem can be a model for multicultural city, especially not with all the extremists that are governing today’s government. And for my part, I’m also for dividing it between the Jewish State and the Arab State. The idea of the two state solution, I don’t see practically how we can have it. So I… I can only be pessimistic.

In 1961 Eliezer Whartman of the Israel State Archives conducted a series of interviews with 31 of the 37 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. For the full interview with Daniel Auster, see here.

For an overview of Auster’s tenure as Mayor of Jerusalem, see historian Mordechai Naor’s Haaretz article.

For a recent survey of Jerusalem’s municipal elections, including the Auster years, see Yechiam Weitz’ “Municipal Elections in the Holy City: Campaigns, Results, and Coalition Building in Jerusalem, 1948-1973.”

For a Palestinian perspective on the upheaval within the Jerusalem municipality in 1948, see Haneen Naamneh’s 2019 article, “A Municipality Seeking Refuge: Jerusalem Municipality in 1948.”

For a classical novel about Jerusalem in 1948, see Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre’s O Jerusalem.

For a wonderful history of Jerusalem, which charts 3000 years of – as the author wrote – faith, slaughter, fanaticism and coexistence, see Simon Sebag Montefiore’s Jerusalem: The Biography.

For a podcast episode (and accompanying write-up) about Auster, see tour guide Rafi Kfir’s “Ahavat Yerushalayim” (in Hebrew).

Here is the 29-person list that Auster headed in his failed bid for Israel’s first Knesset in 1949, and here is a collection of photographs of Auster at the National Library (including this one with Chaim Weizmann).

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubber is Yoav Yefet. A special thanks to our go-to Brit, Jacob Lazarus.

The end song is Ir HaElohim (lyrics and music – Shaanan Streett, Itai Peled, Omer Mor (Itzik Ptzatzati/Isaac DaBom), Moshe Asraf, Yair (Yaya) Cohen Harounoff, David Ariel (Dudush) Klemes, Shlomi Alon and Guy (Margalit) Mar), performed by Hadag Nahash.

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.