Pigging Out was supposed to come out long ago: The stories had been recorded, drafts had been written and we were all set to share our porcine tales with the world. But then, Haaretz published an extensive investigation into allegations of rape and sexual abuse supposedly committed by Yehuda Meshi Zahav.

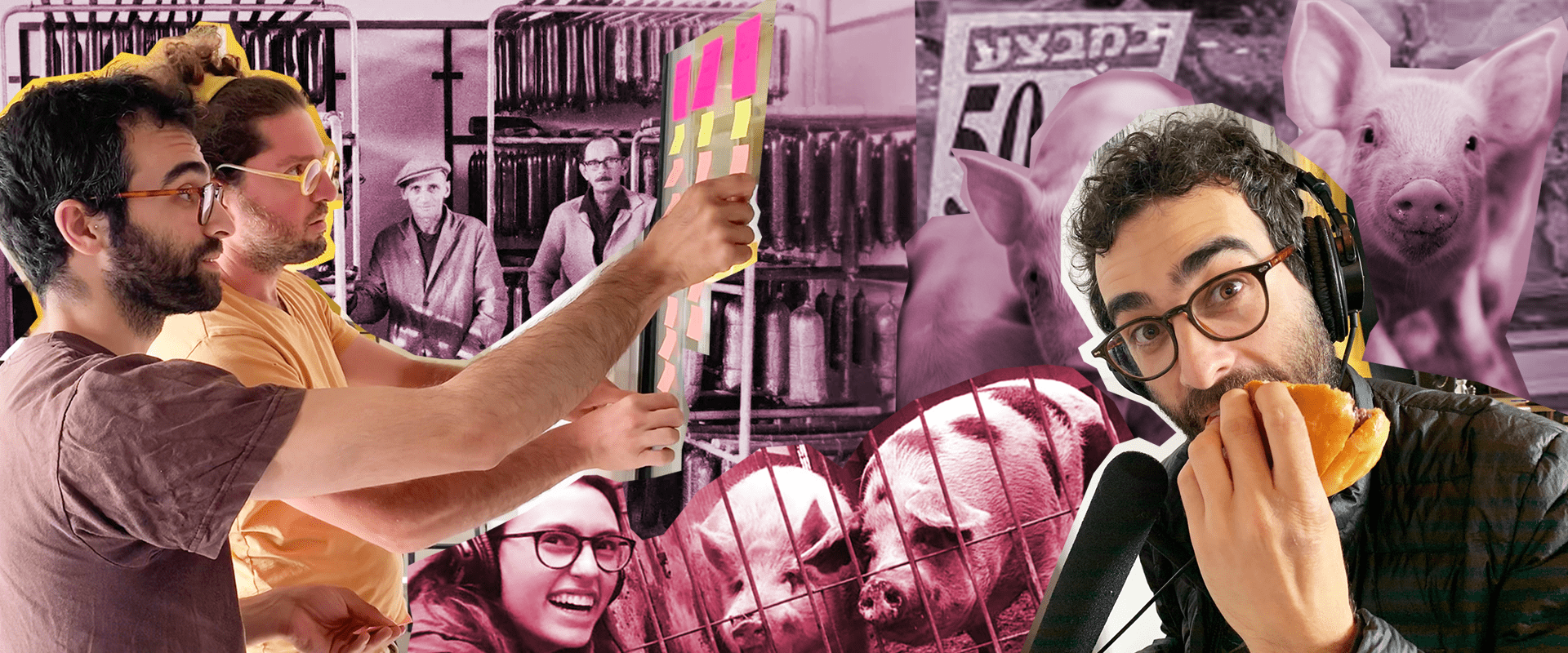

Why and how did that delay our episode by nearly a year? Mishy Harman and Yoshi Fields discuss some of the ethical dilemmas that accompany and underscore our work.

For more extra content and behind the scenes bonuses, head to your Apple Podcast app, and click subscribe.

Get a taste of the behind the scenes of our most recent episode “Pigging Out.”

Act TranscriptMishy Harman: Hey Israel Story listeners, it’s Mishy. I am here in the studio with our producer, Yoshi Fields, hey Yoshi.

Yoshi Fields: Hey Mishy.

Mishy Harman: How are you doing?

Yoshi Fields: Good.

Mishy Harman: And as an extra bonus we are going to give you a little behind-the-scenes peek into the production of the episode that we just released about pigs in Israel. And Yosh, you worked on the story that we ended up calling “A Zionist Pig” for how long?

Yoshi Fields: I started before COVID. So more than a year.

Mishy Harman: OK, you’re a real pig expert.

Yoshi Fields: Yeah.

Mishy Harman: It was actually slated to be an episode in our last season.

Yoshi Fields: Correct.

Mishy Harman: And one of the reasons that that didn’t happen was what we are here to talk about.

Yoshi Fields: Yeah. So for the pig story, we interviewed a lot of different people – activists, farmers, intellectuals, reporters. Basically, one of the main interviewees for the story, we ended up having to cut. That interviewee was Yehuda Meshi Zahav.

Mishy Harman: Who is Yehuda Meshi Zahav?

Yoshi Fields: Well, to begin with, he’s an ultra-Orthodox Jew.

Mishy Harman: In fact, he’s, I would say, the most well-known ultra-Orthodox Jew in Israel. He’s sort of a national figure.

Yoshi Fields: Right. At the time, he was very famous because he was the head of ZAKA, which is an emergency relief international organization. He was also in the news a lot around that time, early COVID days, as sort of this bridge between ultra-religious and secular. And specifically, he had lost his parents to COVID. And it was at a time when there was a lot of religious leaders talking about how they shouldn’t follow COVID safety protocol. And he was saying, “no, we really have to focus on this, this is very important.” So he was very popular. In fact, he had been nominated and was going to be awarded the Israel Prize, which is the biggest prize you can get in this country.

Mishy Harman: And we wanted him to talk about pigs?

Yoshi Fields: Right. He was actually a huge activist against pork in Israel. In the 80s in particular, he was at a lot of protests, and he’d had this confrontation with a butcher in Jerusalem. He was a really interesting person to talk to because he could really speak to the fight within Israel over pork and his personal experience with it.

Mishy Harman: And what was the interview like?

Yoshi Fields: You know, he’s a very captivating person, was my experience. I remember as I left talking to a fellow producer who was with me at the time, and I said, like, “wow, like, there’s something about his eyes that was just like, just really drew me in.” I like had felt like I was in the presence of someone who was powerful and, and had like this sort of crazy charisma.

Mishy Harman: Going in did you think that he was going to become a central figure in your story?

Yoshi Fields: Yeah, absolutely. He was going to talk to what had happened in the 80s, which was a really important part in the history of pork in Israel. So that was gonna help us bring that section alive in our story. And also just talk to, you know, religious views on pork in Israel.

Mishy Harman: Right, and what did he tell you? What did you hear from him?

Yoshi Fields: He told us about that experience in the butcher shop, for example, in Jerusalem, where he had gone to tell this butcher like, “you shouldn’t be selling pork here.” But before he could even like, start speaking, he had – you know – maybe gotten a few words out, and he says the butcher came up to him and literally shoved pork into his mouth. And, of course, he was shocked, but also was like just deeply in his soul kind of feeling of… that he had been in some way abused. He said, he like threw up and it was this horrible, horrible moment for him. To me, it was interesting at the time to hear that because it really felt that this is something he really cares about deep, deep down. It wasn’t just like some, you know, headline thing that he wanted to get involved in. It was really a personal issue for him.

Mishy Harman: That sounds like a pretty crazy story.

Yoshi Fields: Yeah.

Mishy Harman: Did that seem credible?

Yoshi Fields: It did. I worked on fact-checking it. But it became clear we’re not going to use it at all.

[Music]

Mishy Harman: OK, so you wrote an entire draft in which Yehuda Meshi Zahav is a central character.

Yoshi Fields: Right.

Mishy Harman: And the story was basically ready to go.

Yoshi Fields: Right. It had already been a long time working on it. We were excited to air it. And then it was March 11. I woke up read Haaretz, as I often do, and there I think it was the headline, like the first article that day was you know something about Yehuda Meshi Zahav accused of raping boys and girls and men and women for decades.

Mishy Harman: And then we find ourselves in this strange situation where we have a story in which one of the central characters is now suddenly accused, in a newspaper exposé, of sexual misconduct and molestation and rape and what were you thinking?

Yoshi Fields: You know, I think that there are a lot of examples in our work of like, ‘who do we want to give a platform to?’ And this is something we talk about also, within Israel Story, we’ve had many meetings of like, ‘well, do we want to interview this person? Do we want to have them on our show?’ For me, this was not one of those times. It was pretty clear, I think, from the very beginning, this is not someone we want to give a platform to.

Mishy Harman: Even though the accusations had nothing to do with what he was talking about, in this specific story.

Yoshi Fields: Right. It felt very clear that even though this is a story about pigs, where he’s a character talking about pigs, nothing to do with this Haaretz article, it felt pretty clear there’s no way we could air it as is, and we talked about it a couple days later, and I think you were like, “Yosh, like, we’re gonna have to find a replacement.”

Mishy Harman: That is true. I just now in this conversation, want to push back on that.

Yoshi Fields: Yes.

Mishy Harman: And say like, well, I mean, we don’t know what goes on in the lives of all of our interviewees. We interview hundreds or thousands of people, some of them probably have very problematic records. Is it really our responsibility to be policing that in terms of who we allow to participate, or to be heard on our episodes?

Yoshi Fields: It gets complicated and unclear. Like there’s, you know, a spectrum here. We’ve certainly had people on our show that I really feel diametrically opposed to in terms of their political beliefs. And yet, we’re interviewing them about a love story. And we’ll, we’ll still do that story. And I think it’s really important to the ethos of our show that we’re about bringing really personal stories and the humanity of all of us. Again, here was a guy – he was being accused of doing this thing that was so horrible, like, it’s unequivocally ‘this is not OK in our society, this is horrible.’ And such a sensitive and triggering issue for so many people. I felt this then and I still feel this now that this was not in gray area.

Mishy Harman: So do you think that there’s no room for criminals to be heard on a show like ours?

Yoshi Fields: No, I definitely think there’s room for criminals. If we were going to do a show about Yehuda Meshi Zahav and we were going to talk to him about his life and his experiences and dig into these accusations and make a story about these issues. Not just giving him a platform to say his experience, but interviewing other people – if they’re willing to – who are affected by it, giving lots of different perspectives. And I think making it very clear that the actions were not acceptable in any way, no matter the reasons, then that could be a really interesting story. A story where we don’t touch on those issues, I think is the biggest problem to me.

Mishy Harman: Yeah, it’s an interesting question. Because I mean, one of the things that we talked about at the time when this news about Yehuda Meshi Zahav came out was, well, OK, well, maybe we leave him in the story, but add some sort of disclaimer, “that’s Yehuda Meshi Zahav whom, as you might have heard, has recently been accused of, you know, X, Y, and Z.” Many many years ago, in one of our earliest episodes, we had a different – though, in some ways, analogous – instance, where the Chief Rabbi of Zefat, Rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu, was a relatively minor character in the story that we did about Chaya the ultra-Orthodox woman from Zefat who is a serial adopter of babies with down syndrome.

Mishy Harman (from episode): Here’s Rabbi Eliyahu.

Shmuel Eliyahu: When they aren’t biological siblings, then halakhically there’s no problem.

Mishy Harman: And for many people, Shmuel Eliyahu is a figure of authority and many people have tremendous respect for him. He’s definitely a very learned rabbi with tremendous following. His father was Chief Rabbi, he’s often talked about as a candidate for being a Chief Rabbi. But he also is known for making these very controversial proclamations about LGBTQ people, about Arabs, and I needed to include him because – unlike the situation with the pigs where you know, we chose Yehuda Meshi Zahav because he was a good candidate to tell that part of the story, but we could have also chosen other people – in Chaya’s story Shmuel Eliyahu was a big part of that story. We couldn’t sub him out for someone else. And I thought very carefully, should I say, you know, “that’s Shmuel Eliyahu who you probably also know for his statement about not renting apartments to Arabs in Zefat” or something like that. And ultimately, we decided not to include that detail, just because it really had nothing to do with the story that we were telling. It’s an interesting case, I mean, having nothing to do with it both makes it more complicated and less complicated.

Yoshi Fields: Right. When we tell a story, we have to choose the details we’re going to put in. So of course, we’re not going to add all these details. But that detail, right, it’s a question of is it important, even if it’s not important to the narrative story, is that an important detail? I think also, you know, with the head rabbi you’re talking about, like, I don’t personally know his views, right? And that would take me out of the story more, but with Yehuda Meshi Zahav, for example, especially at the time, like, that was what a lot of people were talking about. And that was a headline, and in the news and also internationally.

Mishy Harman: Right. It was the biggest news item for a while in Israel.

Yoshi Fields: Right. So there, it was going to be the first thought of many who listened. I also just wouldn’t want to have someone who has going to potentially trigger so many different people. I don’t want to have that in our stories if we can avoid it, despite the fact that it meant that we had to, you know, rethink the story, and it led to many different interviews and changing the structure.

Mishy Harman: Alright, so we decided to remove Yehuda Meshi Zahav from the story. Then what happens? I assume, you know, many listeners think, ‘well, OK, so you just find a new character, you sort of plug him in where Yehuda Meshi Zahav was.’ Is that how it goes?

Yoshi Fields: No, you know Yehuda Meshi Zahav had his own unique take. So there was no way we could just find another person who had the same experience, like everyone has their own experience. So we needed to find someone else with their own personal experience, shine their own light and their own take on what had happened. And, you know, he was a very big figure, especially around the 80s. Multiple people I talked to for this story who were involved in the issue around pork in the 80s, I had asked, “who would you say was like at the forefront of the religious side of things?” And Yehuda Meshi Zahav came up a lot. So it wasn’t just we could find another Yehuda Meshi Zahav. So we interviewed I think like six or so people, some of them became part of the story, some of them just sort of informed us but we don’t end up hearing their voices. A bit of restructuring. A lot more interviews. Honestly, I think it’s a better story for it. It’s certainly a different story.

Mishy Harman: And then shortly thereafter, there was a development in the Yehuda Meshi Zahav story.

Yoshi Fields: Right. In the weeks that followed that initial report from Haaretz, many other people came forward with similar allegations. Criminal investigations began, he was going to be criminally charged on several accounts, and there was going to be a big TV exposé on what was happening. And just hours before that TV exposé aired, he tried to commit suicide. And then he was rushed to the hospital, stabilized, but in a coma and he’s still in a coma today.

Mishy Harman: Right. All right. Well, Thanks, Yosh. And thanks for sharing this really complicated and interesting story of the history of the pork industry in Israel.

Yoshi Fields: Yeah, my pleasure. I’m glad it’s finally been aired.

Mishy Harman: Alright, see ya.

Yoshi Fields: See ya.

Mishy Harman: Bye, listeners.

Naomi Schneider edited and scored this special with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Sela Waisblum created the mix.