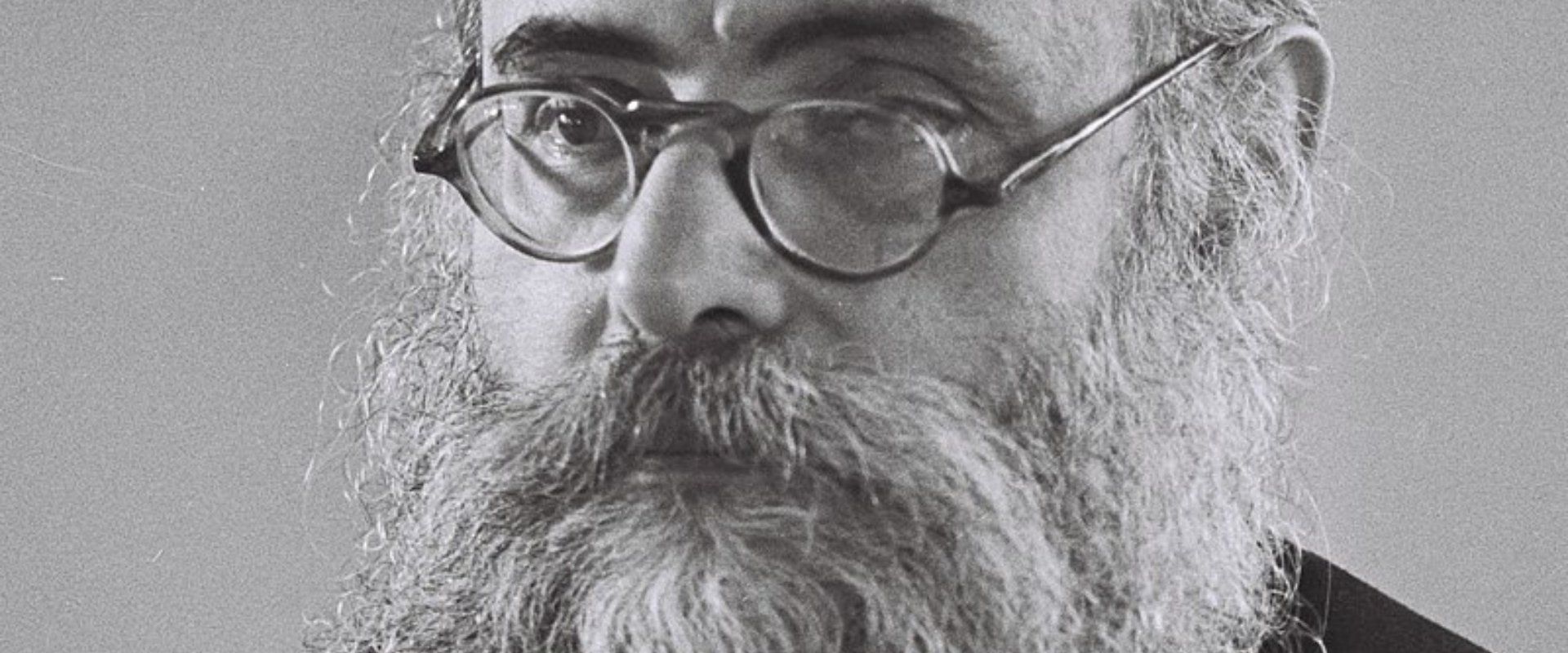

Yitzhak Meir Levin

- 34:30

- 2023

Rabbi Yitzhak Meir Levin was – in every way possible – Hasidic royalty. He was born in 1893 in the Polish town of Góra Kalwaria, or – as it’s known in Yiddish – Ger. And was not only the grandson of the third Gurreh Rebbe, the Sfas Emes, but also married to the daughter of the fourth Gurreh Rebbe, the Imrei Emes.

In 1930, at the age of 37, Rabbi Levin was appointed the head of the Polish branch of Agudas Yisroel, a Haredi political movement that – in pre-war Europe – had an estimated one million followers.

In the Spring of 1940, the top rabbis of the Gurreh hasidic court – who were wanted by the Gestapo – all went into hiding in Warsaw. An emergency message was soon conveyed to their followers in the United States, and thus began a chain reaction that resulted in a handful of visas being smuggled into occupied Poland. These were, naturally, given to the leadership – including Levin – who reluctantly left behind children, grandchildren and hundreds of thousands of followers, most of whom would ultimately be murdered by the Nazis.

Levin arrived in Mandatory Palestine in May 1940. Once here, he was a member of the Jewish Agency’s Rescue Committee for European Jewry, where he repeatedly clashed with secular Zionist leaders, who often found themselves in an impossible situation: While millions of Jews – including their own family members – were being slaughtered in Europe, they were busy trying to build a new society in the Land of Israel. With extremely limited resources at hand, how do you decide what should take precedence?

Levin’s greatest nemesis was fellow future signatory of the Declaration of Independence and Israel’s first Interior Minister, Yitzhak Grünbaum, who went on record saying that not a single cent of the JNF’s funds ought to be spent on rescuing Europe’s Jews.

During those first years in the Land of Israel, Levin was forced to plot a path through the thickets of Jewish and Zionist politics. Should the Agudah party support the establishment of a State, or else adopt an anti – or at least a non– Zionist stance? His answer to this question would have lasting repercussions that continue to reverberate within Israeli society to this very day.

As part of the dilemma, he and other Haredi leaders negotiated matters of religion and state, including – and perhaps most famously – the exemption from military service for 400 yeshivah students, shetoratam umanutam, or whose “studying is their trade.” This compromise eventually ballooned into a widespread and controversial phenomenon with extensive social, political and economic ramifications.

In June 1947 Levin was among those who managed to secure what has come to be known as the “Status Quo” Letter. In that now-famous document, Ben-Gurion promised – among other things – that Shabbat will be the official day of rest in the state-to-be, that kitchens in public institutions will be kosher, and that matters of marriage and divorce will adhere to the dictates of Orthodox Judaism.

With these assurances in hand, Levin agreed to sign the Declaration, despite his many misgivings about its secular nature. Inking his name was, perhaps, made slightly easier by the fact that he didn’t actually attend the Declaration ceremony itself. On May 14, 1948, as the members of Moetzet HaAm congregated in Tel Aviv, he was out fundraising for Agudas Yisroel in far-away New York City, and added his signature to the scroll later on.

After the establishment of the State, Levin served as Israel’s first Minister of Welfare. Four years later, he quit his cabinet post in protest over the notion of women serving in the IDF.

He died in Jerusalem in 1971, at the age of 78, and was buried on the Mount of Olives.

Yitzhak Meir Levin

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: there were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

Today we’ll meet Yitzhak Meir Levin, and his great-grandson, Hanoch Zvi Rubinstein. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Further Reading

In 1961 Eliezer Whartman of the Israel State Archives conducted a series of interviews with 31 of the 37 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. For the full interview with Rabbi Yizhak Meir Levin, see here.

For a vivid account of the life and times of Rabbi Yizhak Meir Levin, see Yisrael Rubinstein’s biography, Meir LaDoros (Hebrew).

For a zoomed-out look at Levin’s life’s work, see this article from Makor Rishon (in Hebrew).

For an historical perspective on Levin’s decision not to serve as a member of the Judenrat, see this article, from the Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Center, on the history of the Warsaw Ghetto.

For the ‘Status Quo Model,’ as presented by Ben-Gurion to Levin and the Agudas Yisroel movement, see this article, by Supreme Court Justice, Daphne Barak-Erez, as well as this Kikar Ha’Shabbat article, in Hebrew, concerning the famous June 1947 letter itself.

For background on why the Agudas Yisroel Party opposed the appointment of Golda Meir as prime minister in 1969, see this article by the National Library staff.

For a video clip of Former Supreme Court President Aharon Barak putting on Tefillin, see here and here, and for Sephardic Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Yosef’s scathing critique of Barak’s unfamiliarity of the prayer, see here.

Lastly, here is Levin’s obituary in the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Credits

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was edited by Adina Karpuj and mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubbers are Yoav Yefet and Jonathan Brenner.

The end song is Niggun Ger (arrangement – Eli Klein and Yitzy Berry), performed by Moshe Duvid Weissmandel accompanied by the Neshama Choir, conducted by Itzik Filmer.

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.

Wartime Diaries

Wartime Diaries