“The Wall” Part III – The Invisibles

- 58:24

- 2019

Walls are something you can see. Something you can touch. Something you can run into and get a nasty bump on your head. Or… are they?! In our episode today – part three of our miniseries – we tell the stories of three walls that won’t appear on your typical map. Three walls you’d probably miss unless you heard about them, well… here. But don’t think that makes them less significant or present in daily Israeli society. Not at all. In fact, they help us trace our history all the way from its earliest beginnings to its menacing future.

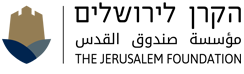

Prologue: Kacha Lo Bonim Choma

Mishy Harman talks to Yoram Arbel, Israel’s quintessential sportscaster. Together they go back in time to Ramat Gan, 1989, where – in the middle of a pivotal World Cup qualifying match between Israel and Australia – an unimaginably iconic catchphrase was born.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): If there’s one guy who knows more than almost anyone else in the world about Israeli walls, it’s this man.

Charlie Yankos: Yeah, certainly. It’s Charlie Yankos here, former Socceroo captain.

Mishy Harman (narration): Now, just in case you’ve never heard of the Socceroos…

Charlie Yankos: Well, the Socceroos are the Australian national soccer team, named after the kangaroos (if you want to call it that) that we have in Australia, so it’s the logical name having it as Socceroos.

Mishy Harman (narration): I’m not exactly sure what he means by “if you want to call it that…” In any event, nowadays Charlie’s a successful businessman in Sydney.

Charlie Yankos: That’s correct. Yeah, Sydney, Australia.

Mishy Harman (narration): But back in the 1980s, Charlie was the nightmare of soccer strikers all the way from Argentina to Greece. He was a tall, fierce defender, who spent most of his time tackling oncoming traffic.

Mishy Harman: But you also had a specialty with free kicks.

Charlie Yankos: I wouldn’t say a specialty. I think I just had a little bit of luck with them more than specialty.

Mishy Harman (narration): So you might be wondering what a jovial Australian former footballer with a thunderous free kick is doing on our Israel Story episode. Well…

Mishy Harman: Charlie, you know that you’re a household name in Israel, right?

Charlie Yankos: Well, I’ve heard a couple of things, but it’s been thirty years, so I don’t know why.

Mishy Harman (narration): I’ll tell you why. It’s because on Sunday evening, March 19, 1989, Mr. Charles Theofolos Yankos entered the Israeli pantheon, for good. You see, ever since the country’s establishment in 1948, international sports associations didn’t quite know what to do with Israel. Which continent did we belong to? Europe? Not really. Africa? That seemed off as well. Asia maybe? Yeah, Asia could work. But before long Muslim countries such as Turkey and Indonesia refused to play against Israel. Games in Iran got out of hand. And in 1986 FIFA, the International Football Federation, came up with a solution, which – I should point out – didn’t exactly make a ton of geographic sense.

Yoram Arbel: [In Hebrew] We played in Oceania.

Mishy Harman (narration): Henceforth, we’d compete in Oceania. Israel, of course, was thrilled. Let’s just say that Fiji, Taiwan and New Zealand are no Brazil or Italy. With this geographic anomaly, we actually stood a chance of qualifying for the 1990 World Cup. But first, we’d have to get past the only serious opponents in the area. And so, two days before Purim 1989, the mighty Socceroos came to Ramat Gan. Here’s Yoram Arbel, the game’s TV announcer.

Yoram Arbel: We felt like we might be able to get past the Australians. And that’s why this game was so important. Because if we beat them, we’d be in an excellent position to qualify.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yoram is like the Israeli John Madden or Vin Scully. He’s been the voice of sports for the last fifty-seven years.

Yoram Arbel: [In Hebrew] From sixty-two.

Mishy Harman (narration): Ever since 1962. He’s a constant fixture in Israeli living rooms, and has broadcasted basically every single soccer game possible.

Yoram Arbel: Yes, it’s… it’s true. An entire generation was brought up listening to me.

Mishy Harman (narration): Anyway, that evening the stadium was packed. More than forty thousand people were in attendance.

Yoram Arbel: The fans were very anxious. Everyone knew this game was “live or die.”

Charlie Yankos: Look, I remember it was very hostile in terms of the environment.

Mishy Harman (narration): Sixty-eight minutes in, one of the Australian players touched the ball with his hand and Israel was awarded a penalty kick. Charlie, the Australian captain, tried – uselessly – to argue with the ref. Eli Ohana, my childhood idol, took the penalty shot. Israel one, Australia zero. The crowd went wild.

But exactly five minutes later, the mood in Ramat Gan changed. Australia got a free kick, about twenty-five meters away from the Israeli goal. Boni Ginzburg, our national goalie, arranged the human wall.

Now, in soccer, like in life really, a wall is meant to keep things out.

Charlie Yankos: Look, the wall is just an obstacle more than anything else. The whole idea is that the ball should not be going past that wall, right?

Mishy Harman (narration): But, Charlie, you’ll recall, had a secret power.

Charlie Yankos: I had this sort of air of confidence in terms of taking free kicks.

Mishy Harman (narration): And Yoram Arbel, the commentator, knew it.

Yoram Arbel: When the Australians got that free kick, I remembered that Charlie Yankos wasn’t a sophisticated player who know how to curl the ball. But he’d kick the ball with unimaginable power. And I said to myself that if he manages to get it past the wall, the wall has screwed up.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yoram even warned the viewers. “We’ve got to pay attention to the right hand side of the wall. Perhaps another player there would help. We have to be careful of Charlie Yankos! This distance is nothing for him.” Charlie, determined and focused, ran to the ball.

Charlie Yankos: And that’s when I saw the gap. And all I can remember was, ‘I’m gonna have a shot at this. Doesn’t matter what happens at the end of the day. I’m gonna go for it!”

Yoram Arbel: That bastard saw the corner of the goal, and he just went for it. He banged an amazingly fast ball. No one even had time to blink.

Charlie Yankos: And then I just went up there and hit it, and I was just lucky that it went in.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yoram was irate. “That’s what I was saying,” he yelled, “I told you so!”

Yoram Arbel: And when it went in, I was unbelievably angry. More than I’ve ever been upset in a game my whole life.

Mishy Harman (narration): In his despair, he spontaneously came up with what would soon become his most famous phrase.

Yoram Arbel: It came out of my gut. Out of my kishkes. “That’s no way to build a wall.” And the rage that I felt, and the feeling of frustration, what can I say? It caught on. It spread like a wildfire.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yoram isn’t exagareting. For some reason, that seemingly mundane statement of his, uttered in anguish in the middle of a qualifying soccer match for the 1990 World Cup, entered the Israeli national consciousness. It’s right up there with Herzl’s “im tirtzu ein zo agada” (“if you will it, it isn’t a dream”).

Ben-Gurion’s “anu machrizim ba’zot” at the Declaration of the State.

David Ben Gurion: [In Hebrew] We hereby declare the establishment of a Jewish State in the Land of Israel.

Mishy Harman (narration): Or Rabin’s “I’ll navigate,” after winning the 1992 elections.

Itzhak Rabin: [In Hebrew] I’ll navigate the coalition negotiations. I will determine who shall be the ministers.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yeah, it is that pervasive.

Yoram Arbel: Somehow this sentence rang true to the Israeli ear. It became an idiomatic phrase. And one day, when I exit this world, I’ll leave behind this tiny little legacy, in the shape of this short sentence, which has really become part of the Israeli lexicon.

Mishy Harman (narration): I asked Yoram why this phrase, out of the tens of thousands he’s rendered over the years, went down in history.

Yoram Arbel: Look, by and large it says that we are doing something wrong. And that’s why it also spills over into other associations. When the government isn’t working, it’s “that’s no way to do this” or “that’s no way to do that.” We build something – neh, something is missing. We go for some bold political move – eh, we somehow spoil it.

Mishy Harman: If you could give Israelis some advice on how to build a wall, how to construct a better wall, what would you say?

Charlie Yankos: Yeah, don’t take the bricks away very quickly. Make sure they stay there for a while.

Mishy Harman: How does it make you feel to be the wall expert of Israel?

Charlie Yankos: The wall expert? Without an engineering background. Interesting… [laughs]. How funny.

Act I: Building a Wall

When Yochai Maital recently tried to send a text message with some good news to his friends and family, he discovered that Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp had all simultaneously collapsed. That got him thinking. How much of his life, he wondered, relied on web-based platforms? What would happen if they all crashed at once? And what, really, was protecting our ever-expanding digital presence? Luckily, he knew just the man to ask: Gil Shwed, an enthusiastic computer geek from Beit HaKerem, Jerusalem who – among many other things – is widely considered to be the inventor of the modern computer firewall. Gil recounts how, from his start at a local Orthodox community center, he went on to found and run Check Point, one of the world’s most influential software giants.

And… ever thought you’d join an island retreat of Indonesian hackers? Now is your chance. Check out this video of them celebrating.

Act TranscriptYochai Maital (narration): On the morning of July 3rd, my wife Dafna and I stepped out of an ultrasound clinic. We were holding an oversized manila envelope. And inside it were the very first images of our third child, quickly growing inside of her.

Like all Israelis, we’re connected with our families, friends, colleagues, army buddies, etc. in an endless net of overlapping WhatsApp groups.

We had been waiting for this day to share our happy news. And now that it had come, we decided that the easiest, most fun way to let everyone know at once, was to send a single WhatsApp message. No words. Just a cute, grainy ultrasound image of the fetus’ hand. We looked at each other, smiles on our faces, and pressed ‘send,’ expecting – of course – a torrent of Mazal Tovs to start flowing in.

None came.

After a few long minutes, a friend finally texted back – “can’t see the image.” My nephew was even more succinct, sending back a question mark. It soon turned out that WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook had all failed at the exact moment we had sent out our good news. None of our friends or family could see the picture. By the evening, the glitch had been resolved, and the news had spread far and wide. Now I’ll admit, this tech breakdown was, at most, a minor inconvenience to us.

But it got me thinking.

Just how much of my life relied on web-based platforms? And how vulnerable would I be if they malfunctioned, as they had, all at once? In the real world a tree may fall and block a road, a phone line might accidentally be cut by a careless construction crew. But it’s inconceivable that the entire physical infrastructure could simultaneously break down. A massive Internet crash would pretty much bring my life to a halt.

Facebook barely acknowledged there was any problem at all. When the services were back up, they simply issued a short and unsatisfying statement:

Facebook Representative: “Earlier today, some people and businesses experienced trouble uploading or sending images, videos and other files on our apps and platforms. The issue has since been resolved and we should be back at 100% for everyone. We’re sorry for any inconvenience.”

Yochai Maital (narration): My good news wasn’t urgent by any means, it could wait until the evening. After all, there are another twenty-five weeks to go, give or take. But what if this had been an urgent message? What if it had been a matter of life and death? What, if anything, was being done to protect us against a worldwide collapse of electronic communications? Luckily, I knew just the man to ask.

Yochai Maital: I was wondering, maybe as a first question, if you remember your first computer?

Gil Shwed: I actually never had a first computer. I never owned a computer at home. There was like an orthodox community center and they had the first programming class. The computer name there was, it doesn’t exist anymore the name was Soul 85.

Yochai Maital (narration): It was love at first sight. Gil grew up in a middle-class secular family in Jerusalem’s laid-back neighborhood of Beit HaKerem. His father was a computer engineer, back when computers were the size of a room. So from a young age, Gil was attracted to the subject. Everyday he would wait anxiously for the school bell, run to the bus and hustle to the community center, trying to get there early so he could steal some extra time exploring this mesmerizing new machine. From the moment his fingers touched the keyboard, his mind took off.

Gil Shwed: I’ve started working on computer when I was ten. I got my first job when I was twelve or thirteen. That was a summer job and I was a programmer in a company in Jerusalem.

Yochai Maital (narration): After a year-and-a-half, Gil realized…

Gil Shwed: That I’ve sort of exhausted what I had to learn there.

Yochai Maital (narration): So at fourteen, he quit his job…

Gil Shwed: Yeah.

Yochai Maital (narration): And got a new one at the Hebrew University.

Gil Shwed: In the Chemistry Department. I was their system administrator. I wrote program, I maintained the computer system.

Yochai Maital (narration): Jealous of all the students around him, struggling with their C Sharp and multivariable calculus homework, he thought to himself, “I can do this.” So he walked up to the admissions building.

Gil Shwed: So I knocked on their door literally. I said, “I want to learn here.” They said, “OK, but you are fourteen.”

Yochai Maital (narration): They shooed Gil away, but he kept coming back.

Gil Shwed: Every day I went there. I knocked on their door, I said, “is there something new?”

Yochai Maital (narration): Finally, they caved and let him sit in on some classes. By fifteen, Gil was already enrolled as a full-time computer science major.

Sitting in front of a billionaire, I suddenly realized that I felt bad for him. It seemed as if he missed out on having a childhood.

Gil Shwed: Our top skills are actually when we’re fourteen or fifteen.

Yochai Maital: Emm-hmm.

Gil Shwed: That’s the time when we are mature enough to work hard and if we are interested in something, we can dedicate all our resources to that. An adult person has to worry about, you know, making a living, about starting a family, about preparing your own food. A kid that’s fourteen or fifteen – if they’re excited about something, if they’re interested about something, they can dedicate all their energy to that.

Yochai Maital (narration): By eighteen, Gil’s carefree days were over. Like most Israelis, he was called up to the army. The IDF immediately realized that this nerdy kid, with over six years of experience under his belt, was a serious asset. He was assigned to the eight-two-hundred unit – Israel’s equivalent of the NSA.

Gil Shwed: My task was to connect two IP networks actually in the same building, across the wall.

Yochai Maital (narration): It was around that time that he was exposed, right at its inception, to this new invention called the ‘World Wide Web.’

Gil Shwed: The Internet back then was an academic network. The web didn’t exist, so I mean the Internet was about sending emails, but still it was a huge revolution in my mind.

Yochai Maital (narration): By 1989, twenty-one-year-old Gil was out of the army.

Gil Shwed: I looked at my world and I said, “that’s going to be part of the future.” Of course I couldn’t imagine how much the Internet would take over our entire life. At least for me, it looks like this is going to change the world.

Yochai Maital (narration): But knowing exactly in which way it would change the world, and how to make money out of it? That was more difficult.

Gil Shwed: So when I left the army, I actually had a bunch of ideas, including the idea of Check Point.

Yochai Maital (narration): The idea of Check Point? Well, to try to explain, I’m going to take you on a brief journey, more than three thousand years back in time.

A loosely-bound group of tribes called the Israelites are an emerging power in the Land of Canaan. But they can’t seem to stop fighting one another. After a military leader from the tribe of Menashe, one Yiftach HaGiladi, brutally crushed a rebellion launched by the neighboring tribe of Ephraim, word got to him that survivors were hiding among his people. So, Yiftach and his men set up the world’s first firewall – or checkpoint – at a narrow crossing along the Jordan river. Yiftach’s men had to act wisely. They couldn’t start interrogating every single person at length – that would create a ruckus and likely alert the interlopers. So, Yiftach came up with an ingenious plan. His men had just one simple, and seemingly innocuous, request of each passerby – “please say shi-bo-let” – the Hebrew word for a stock of grain. Now Bnei Ephraim had a characteristic lisp. They couldn’t produce the ‘SH’ sound, so anyone pronouncing “shibolet” as “sibolet,” was killed on the spot. All told, over forty-two thousand people died that day.

Fast forward to the early nineteen-nineties – in what would have been the territory of the Dan tribe – Gil was tinkering with a somewhat similar idea. A modern (and hopefully not as ruthless…) version of a checkpoint, or firewall.

Gil Shwed: It should be simple. It should be transparent. It should be fast and make it secure.

Yochai Maital (narration): But he wasn’t convinced anyone would buy it, so he scrapped the idea. Instead, Gil went to work as a software developer. It’s entirely possible that that would have been his life. But then, a few years later, in 1993…

Gil Shwed: The US administration decided that the Internet would be an open network and suddenly every company can connect. And I said that’s my opportunity.

Yochai Maital (narration): The second companies and corporations plugged themselves in, their attention immediately turned to the question of… ‘How to keep people out?’

Gil Shwed: That’s where I called two of my friends and told them, “you remember my idea from three years ago about network security?”

Yochai Maital (narration): Gil and his pals, Marius Nacht and Shlomo Kramer, all handed in their notices, effective immediately.

Gil Shwed: Because the Internet is running very very fast. And we can’t do it part time, we need to do it two hundred percent of our time.

Yochai Maital (narration): They pooled their savings and bought tickets to the first ever Internet security conference in San Diego. When they got back, the three hunkered down in the Israeli version of the startup garage.

Gil Shwed: Our garage was Shlomo’s grandmother apartment. It was small apartment we started in a tiny room next to the kitchen around April.

Yochai Maital (narration): A few months went by.

Gil Shwed: We were sitting there all the summer, programming.

Yochai Maital (narration): By July, the computers were overheating so they expanded into the living room. In those early days, they didn’t even have direct access to the web.

Gil Shwed: We didn’t want to spend the money on direct Internet connectivity, that was too expensive.

Yochai Maital (narration): The first to invest in Check Point was BRM – an Israeli Software company founded by Nir Barkat – who would later become the Mayor of Jerusalem. His company bought…

Gil Shwed: About half of Check Point for approximately $250,000.

Yochai Maital (narration): With that influx of capital, they rented a small office and the trio finally gave poor Shlomo’s grandmother some space. On December 15th, 1993, Gil submitted a patent for what he called ‘Stateful Inspection.’ It was the framework for an easy-to-install program that would keep networks safe. The software, compressed to a mere 1.5 megabytes, could be copied onto a floppy disk and mailed – snail mailed, that is – anywhere in the world. Very quickly, it became apparent that Gil and his friends were on to something. Those floppy disks were flying off the shelf, and they signed a huge deal with Sun Microsystems.

Gil Shwed: When we were less than one year already, our shareholders offered to buy us out and pay us a lot of money.

Yochai Maital (narration): Gil wasn’t even twenty-five and now had the option of retiring as a multimillionaire.

Gil Shwed: Two weeks later another investor come and raises the offer.

Yochai Maital (narration): He turned him down too.

Gil Shwed: Growing in Jerusalem, regular family, I was always… Money was actually something frightening, something bad, believing that if you got too much money, something is wrong. My dream was always about building something and it never stopped.

Yochai Maital (narration): Before long, Check Point was already established in the US and expanding into other markets as well.

Gil Shwed: In the first three years of Check Point, I really gave up everything that I have in life and I really worked literally eighteen hours a day. It’s not just the physical hours and so on; there is an emotional price that’s very very high when you have all the pressure on you and you have no guarantee that it will succeed.

Yochai Maital (narration): Gil’s decision to reject the advice of dozens of savvy business experts and forgo millions upfront, paid off. Check Point’s latest valuation is close to nineteen billion Dollars. It has captured and maintained control of a large percentage of the cybersecurity market. From three employees, the company grew to over five thousand operating in a hundred and ninety countries around the world. Its success is often cited as a catalyst for the Israeli ‘startup revolution.’ But in truth, it could more accurately be described as a ‘high-tech exodus.’

Ehud Barak: Usually Israelis are very good at startups, but much slower or backward in running really big, big companies. And Check Point is a great success, one of the most successful Israeli companies.

Yochai Maital (narration): That’s Ehud Barak.

Ehud Barak: Former Prime Minister of Israel, Minister of Defense and Commander of the Armed Forces also.

Yochai Maital (narration): And Barak is uniquely positioned to talk about the issue because…

Ehud Barak: At the age of seventy-six, I found myself founding a cyber company together with three younger people.

Yochai Maital (narration): As prime minister, he witnessed thousands of successful Israeli companies being bought out and moving their operations abroad. But not Check Point.

Gil Shwed: The headquarter is in Israel and I’d like to think that it will stay like that forever.

Yochai Maital (narration): Gil and Check Point were one of the early players in the cybersecurity world. Today there are many others, vying for a piece of the estimated one-hundred-and-fifty billion Dollar pie. And almost all experts agree that the market is just growing.

Twenty-six years ago, when Gil got started, computers were not yet household items, and networks? Well, they belonged mainly to big corporations. Today, as every house is linked up, and we’re connected through our phones, cars, and appliances, cyber attacks are the fastest growing category of crime across the globe.

Ehud Barak: It’s a main challenge for the whole world right now. The threat is rising dramatically, especially the more sophisticated attacks could make a huge, huge damage.

Yochai Maital (narration): Barak is right, of course. Israel is under constant cyber attack.

Anonymous: This is a message to the foolish Zionist entities. We are coming back to punish you again.

Noam Rotem: A lot of what’s going on is an illusion. We think we are safe, we think we are protected but when you look deeper and you see what’s going on beneath the surface, you should start to be very scared.

Yochai Maital (narration): That’s Noam Rotem.

Noam Rotem: I’m an Israeli hacker and activist.

Yochai Maital (narration): His job is to expose holes in the wall.

Noam Rotem: Getting into their systems and just pointing and laughing.

Yochai Maital (narration): I met up with Noam to try and understand the extent of the threat. What exactly could hackers do? A lot, it turns out.

Noam himself has infiltrated governmental agencies…

Noam Rotem: The Ministry of Education. I got their data four times already.

Yochai Maital (narration): He’s hacked into banks, and utility companies…

Noam Rotem: Israeli Prison Service, the Ashdod Port.

Yochai Maital (narration): Israel’s largest harbour.

Noam Rotem: We had access to everything. Who’s working, where, on which shipment, on which container.

Yochai Maital (narration): Hackers can steal your money, stall your motor…

Noam Rotem: Basically I could log in and shut down your car.

Yochai Maital (narration): Create food shortages…

Noam Rotem: Take out all the industrial refrigerators in a country.

Yochai Maital (narration): Breach dams…

Noam Rotem: You can break the pumps and then the pressure builds and it collapses.

Yochai Maital (narration): And – as Gil told me – even shut down the electric grid.

Gil Shwed: That’s more than doable to take down the electricity grid. It’s very possible from every perspective. These attacks can happen very very fast, much faster than conventional attack. And they can create mass-scale damage, in a way that conventional weapons actually cannot do.

Yochai Maital (narration): Apocalyptic predictions aside, just consider the monetary loss created by cyber crime.

Ehud Barak: Just of theft of IP – of intellectual property – which is numbers like two-hundred billion Dollars annually and so on with, in many case, irreversible damage.

Yochai Maital (narration): In fact, some estimates say total losses reach up to 1.5 trillion Dollars a year.

Maya Horowitz: Ninety-something percent today of all the attack today are just for financial gain.

Yochai Maital (narration): That’s Maya Horowitz.

Maya Horowitz: I’m Director for Threat Intelligence and Research here in Check Point.

Yochai Maital (narration): Maya leads a team whose job it is to investigate cyber threats in order to better understand this new battlefield. Like Gil, she’s ex-8200, Israeli military intelligence.

Ehud Barak: In Israel it’s unique because we have a general draft. Everyone join the army, so basically the cyber units have an access to the best fresh young brains. And some of them are natural hackers. And Israel has a almost natural comparative edge on this issues because we face these challenges of cyber for many years. For security reasons, both defensive, and sometimes offensive.

Yochai Maital (narration): 8200, and units like it, are part of this pipeline fueling high-tech in Israel. Though Maya is a civilian now, she’s still very much in the role of an intelligence officer – collecting data on the enemy, whomever that might be – so that better defensive measures can be devised and implemented. And that makes sense. Conventional warfare has traditionally been in the hands of the state. After all, governments, armies and police forces are the ones we look to to keep us safe.

But today it’s actually global companies like Check Point who are replacing the state in that role. Because, the new cyber-enemies? They can be anywhere.

Gil Shwed: Can be sitting next building. It can be sitting in Africa. It can be sitting in Europe, and there’s nothing in common to them. Some of them are professional and developers. And some of them are amateurs that wants to make money and take tools from the Internet. It’s very hard, if not… I wouldn’t say impossible, but it’s very hard to track the people and see who’s behind cyber-crime.

Yochai Maital (narration): Maya took me around, and had members of her team show me some cases they were working on. They see payment and credit card fraud, extortion through malware…

Adar Waldman: This is definitely the biggest thing that’s going on right now.

Yochai Maital (narration): IP theft, silent network takeovers, and more.

Oded Awaskar: And this is their Indonesian island that they’re living in.

Yochai Maital (narration): Check Point tracks these criminals, and can often even get their name and location.

Oded Awaskar: It’s called Gorontalo, if I’m not mistaken. You can see, you can just see their faces…

Yochai Maital (narration): The criminals largely act with impunity.

Oded Awaskar: This is their logo by the way.

Yochai Maital (narration): This is Oded Awaskar – one of the investigators on Maya’s team. While we were chatting, a group of cheerful Indonesian hackers on his screen were gobbling down a cake adorned with the words…

Oded Awaskar: “We are not hacker.”

Yochai Maital (narration): Actually, it was more like they were stuffing the cake into each others’ faces in this impromptu food fight. The video was an unusual bonus for Oded – not only did he uncover the identity of the cyber criminals he was hunting down, but he found a little party clip lurking on the web to go along with it.

Oded Awaskar: With a drone and editing, I mean it’s… it’s… it’s a pretty good video, I…

Yochai Maital (narration): It made us both smile (you can check it out too, we’ll post it on our website). But those who laugh last, as they say, are the island hackers.

Yochai Maital: So do these Indonesian hackers know that you’re on to them?

Oded Awaskar: No! They do not know yet. I’m guessing that when this story is going to be published, then they are going to be aware of that we’re on to them. Question is, what are they going to do afterwards. They just can say, ‘OK, so they’re onto us, no biggie. No Indonesian government is going to chase us, and put us to prison or jail, or, or even a sentence.’

Yochai Maital (narration): It’s not just Indonisia, Maya explained to me, who turn a blind eye…

Maya Horowitz: Cyber-attacks are probably a large part of the nati0nal income to Nigeria.

Yochai Maital (narration): Some countries take it one step further.

Maya Horowitz: Sometimes there are state-sponsored attacks that just try to get money and we see it mostly coming from… from North Korea, where there are groups that do both espionage and just money theft.

Yochai Maital: Huh, and they’re successful?

Maya Horowitz: Yes, many of them are successful in getting tens of millions of Dollars.

Yochai Maital (narration): From her perch at Check Point’s headquarters, Maya has a bird’s eye view on the cyber armies being amassed around the world.

Maya Horowitz: Wherever you see, you know, a rivalry between nations, and you see it in politics, you also see it on the cyber landscape. But actually on the cyber landscape you also see, you know, the silent wars. [Laughter]. Those that don’t make the news, those that no one talk about, no one is aware of, but still even friends, even countries that are friends, would also want to have information on one another.

Yochai Maital: Can you, like, give examples to that?

Maya Horowitz: No, not really. [Laughter].

Yochai Maital: I had to try…

Maya Horowitz: After ten years in military intelligence, I can keep my mouth shut.

Yochai Maital (narration): But even without her naming names, it is clear that these silent wars are fuelling a cyber arms-race.

Gil Shwed: The NSA, the National Security Agency of the US, they are probably the largest cyber organization. They developed an amazing toolkit to penetrate to almost every system.

Yochai Maital (narration): Two years ago, in 2017, this toolkit, called EternalBlue – was leaked to the Internet by hackers identifying as ‘Shadow Broker.’

Gil Shwed: And that’s the scary part, that we all need to defend ourselves against technology that’s been developed by the best people.

Yochai Maital (narration): Widespread access to the cyber equivalent of WMDs.

Ehud Barak: By definition, attack is much easier than defense. If you are the defender, you have to protect every conceivable access. It doesn’t matter where you are attacked, if the attack is successful and penetrates and can travel easily within your inside, intestines, kind of so-to-speak…

Yochai Maital: Yeah.

Ehud Barak: Digital intestines.

Yochai Maital (narration): I asked Barak what needs to be done in order to defend ourselves?

Ehud Barak: My vision is that cyber will follow the example of the human immune system. Which is really extremely sophisticated, with the capacity to identify any foreign bit as not belonging to self and have different means of attacking them and producing the right antigens to attack. And then keeping the memory – the lessons – from the previous attack. So if something similar comes, it makes a shortcut into the right solution. And I think that should be the source of inspiration for development of cyber defense. And attack will be like the worst kind of viruses that are, you know, the metaphor of viruses is extremely relevant here.

Yochai Maital (narration): Back in the early nineties, Gil had a vision. To make the Internet a safe place. With time, that challenge keeps getting harder but also more lucrative. Even though Gil has personally “made it” in the world – his net worth is estimated at 3.7 billion Dollars (making him the eighth richest person in Israel) – he doesn’t own any yachts, jets or Lamborghinis.

Gil Shwed: For me, that was never the dream. I mean I’ve never… Very few things in our lives we actually build new things and in computers, you can build something new every day. That’s what attracts me today, and attracted me back then to be a programmer.

Yochai Maital (narration): Gil still arrives at the office early, and puts in long work days. It’s clear he has tons of energy and fight left in him.

Gil Shwed: The battle in neverending. There’s always criminals, they’re always there and they always become creative. The number of vulnerabilities that we have in our infrastructure is just going up.

Yochai Maital (narration): Of course, the frightening threats Gil is talking about are not new. I mean, we’ve all witnessed the dangers of hacking and cyber terrorism – from tampering with elections all the way to the delayed sending of ultrasound images. But somehow, sitting by Gil’s side in Tel Aviv, this middle-aged billionaire computer geek made me feel, if just for a brief moment, completely safe.

Anonymous: This is a message to the foolish Zionist entities. We are coming back to punish you again. We will take down your servers, your banks and your public institutions. We will hunt you down. We are Anonymous. We do not forgive. We do not forget.

Act II: Lenny at the Gate

What happens when an internationally renowned artist stands in front of his inspiring muse? Mishy Harman tells a tale which all began when, in November 1957, one particularly prominent New Yorker opened his Sunday morning Times and read about an astounding biblical discovery halfway across the globe.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): On November 17, 1957, a forty-nine-year-old New Yorker – we’ll call him Lenny – opened his Sunday morning Times. And there, at the top of page nineteen, just above a huge Saks Fifth Avenue ad, he stumbled upon an intriguing headline.

“Digging in Israel,” it read, “Supports Bible.” As he skimmed down the page, Lenny learned that Yigael Yadin, Israel’s Indiana-Jones-slash-Carl-von-Clausewitz, had unearthed a massive city gate built by none other than… King Solomon himself.

The gate and adjacent wall were discovered at Hazor, an ancient city north of the Sea of Galilee.

Amnon Bentor: Hazor, it is the number one site as far as the Bible is concerned.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Amnon Bentor.

Amnon Bentor: We have artifacts, we have buildings, we have strata, of – I’ll just give names – for the time of Joshua, time of the Judges, Solomon, Ahab, Jeroboam II. So if you want a reflection of the biblical story, come and look at our gates!

Mishy Harman (narration): Amnon has led the excavations at Hazor for the last thirty years, and, as you can tell, he’s quite fond of the place.

Amnon Bentor: We are the center of everything. [Mishy laughs]. Yeah, we are! It’s not funny.

Mishy Harman (narration): In the Bronze Age, he says, it was…

Amnon Bentor: Like the New York of the time, if you wish. Like the Paris of the time.

Mishy Harman (narration): Amnon, who’s nearly eighty-five now, is a celebrated archeologist. Just this year, on Yom Ha’Atzmaut, he was awarded the Israel Prize in archeology. But back in the late fifties, when the gate was discovered, he was just a young undergrad, basking in the glory of his famous IDF-Chief-of-Staff-turned -professor, Major General Yadin.

Amnon Bentor: Ahh… A picture? You want to see a picture?

Mishy Harman: Sure!

Amnon Bentor: Ahh… Just a minute. Where do I have a picture?

Mishy Harman (narration): Amnon went to his bookcase, and pulled out a large volume. He flipped through the pages and found a group photo of the delegation.

Amnon Bentor: This is the team, working at Hazor, 1958.

Mishy Harman: Where are you?

Amnon Bentor: I am here. That’s me.

Mishy Harman: You were blond?

Amnon Bentor: Sixty years ago. Yes, I was blond. I was blond and I had a lot of hair. So, what was your question again?

Mishy Harman (narration): Anyway, back in New York, good ‘ol Lenny was ecstatic.

Alex Bernstein: He was very excited about the State of Israel in those days.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s his son, Alex.

Alex Bernstein: He actually was there during the war in ‘48.

Mishy Harman (narration): And since, Lenny had been back a bunch of times.

Alex Bernstein: Oh yeah, he went back again and again. He just loved it. He loved the spirit of the place. You could say that my father was a Zionist, absolutely. Yeah.

Mishy Harman (narration): So as he read through that New York Times article, his imagination went wild.

Alex Bernstein: He loved those stories of the Bible. He spoke Hebrew very well. He read Hebrew very well. He knew the prayers. He had gone to synagogue all his life. So he knew all the stories.

Mishy Harman (narration): And now, his creative juices were really flowing. By the time he finished the piece, he was so touched, so inspired, that he had made up his mind. He was going to write an opera about the ‘Solomonic Gate’ of Hazor.

Now, this wasn’t as random as it might sound. Because, you see, Lenny? Well, he was actually better known by another name: In 1957, Leonard Bernstein was a rising star.

Alex Bernstein: Things were happening so fast.

Mishy Harman (narration): That very same year, not only he was named the Music Director of the New York Philharmonic, but West Side Story, the musical he composed, premiered on Broadway.

Bernstein wrote to Yadin, and asked to come visit Hazor. Yadin, himself pretty excited by the celebrity attention and the prospect of a world-class opera being written about his site, immediately accepted. So lo and behold, in the summer of 1958, the famous yet giddy maestro schelped up to the far north of Israel to observe his newly unearthed musical muse.

Amnon Bentor: There are very few of us, who were at Hazor at the time, and I am one of the few, in my old age, so I remember because it was a big story. It was a big story. I don’t know how much we knew about the importance of Leonard Bernstein at the time, but we knew that an important composer, da-da-da-da, was about to visit Hazor. And everybody wanted to see, who and what and wh… We didn’t know who Leonard Bernstein was at the time. I’m sorry.

Mishy Harman (narration): But Bernstein had done his homework. He knew, no doubt, exactly how important gates were in the walled cities of the ancient Near East.

Amnon Bentor: If you have a wall all around the city, how shall people come in and out? So you have a major gate. That’s where everything takes place. That’s where the king sits and receives guests. This is where judgment takes place. Trades. All these things take place at the gate. So the gate is really the focus of everything that happens in the city. The city gate.

Mishy Harman (narration): Given all that, in his mind, Bernstein must have imagined something grandiose. An Israelite version of Paris’ Arc de Triomphe, Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, or Rome’s Arch of Constantine. You know, something that would befit his soon-to-be-written epic opera. So on the day of the visit, an eager Yadin welcomed the maestro to his kingdom, and showed him around the excavation. First he took him to Ahab’s storage rooms. Then he showed him Yavin’s palace. The Bronze Age temple. The city’s casement wall. And finally, they arrived at the wondrous Solomonic gate. Supposedly built three-thousand years ago, by an omnipotent king with a thousand wives.

And at that dramatic moment, when the great creator came face to face with his ancient inspiration, Mr. Leonard Bernstein of Manhattan, New York, learned something fundamental about Levantine archeology.

He learned that you need a lot of imagination.

Amnon Bentor: You know, we archeologists we see two stones and it’s a house, and three stones and it’s a palace, and four stones it’s a gate. Normal people don’t see this.

Mishy Harman (narration): As the animated Yadin pointed here and there, and waxed poetic about biblical kings, all Bernstein could see was a few old stones, strewn on the ground.

Amnon Bentor: There was very little of the gate to be seen. Only the foundations could be seen at the time. This a gate. Everybody can see this. Not everybody… Every first year archeologist can see that this is a gate, but you know, normal people when they hear a gate they want to see something big, enormous. And, in those days, you couldn’t.

Mishy Harman (narration): Bernstein was crushed. His muse, it turned out, was no more than a pile of rubble. Needless to say…

Amnon Bentor: He was very disappointed.

Alex Bernstein: [Laughs]. I came all the way for this, yeah? Oh, that’s funny.

Mishy Harman (narration): The opera, you can imagine, was never composed. Not a single note was ever written.

Mishy Harman: What do you imagine an opera about Hazor would have been like?

Amnon Bentor: I have absolutely no idea. I don’t know.

Mishy Harman: Would you go see it?

Amnon Bentor: I don’t go to see operas anyway, I don’t like opera [Mishy laughs]. I really don’t. I think you can say everything you need, and don’t have to sing it.

Mishy Harman (narration): But despite what Amnon says, one of the most amazing things about creating a podcast, is that sometimes – occasionally – you can alter history. So it is with great pleasure, dear Israel Story listeners, that we bring you a sneak peek of the world premiere of Leonard Bernstein’s never-written operatic hit about King Solomon’s, let’s just say, slightly more successful building project, on Jerusalem’s Mount Moriah.

The most beautiful mountain I’ve ever seen,

Moriah.

It’s more than a mountain,

Moriah.

So I’ll build the most fabulous temple that’s ever been,

On Moriah, King Solomon’s shrine on Moriah.

Moriah, Moriah, Moriah.

I’ll build you and then I’ll retire.

He has a thousand wives.

Nobody is as wise as he.

Moriah, King Solomon’s shrine on Moriah.

The nation will unite.

We’ll build it in a night,

You’ll see.

Moriah, wave my hand and the bricks start laying.

Soon we’ll open the doors to your praying.

Moriah.

And then I’ll retire, Moriah.

Credits

The original music in this episode was composed, arranged, and performed by the Israel Story band led by Ari Jacob and Dotan Moshonov, together with Ruth Danon, Eden Djamchid and Ronnie Wagner-Schmidt. The new lyrics to Leonard Bernstein’s “Maria” (or “Moriah”) were written by Ari Wenig, who also sang it. The end song is our band’s cover of Shomer HaChomot (“The Keeper of the Walls”), written by Dan Almagor, composed by Benny Nagari and originally performed by Zevet Havay Pikkud HaMerkaz.

Additional music by Broke For Free, Lee Rosevere, Dotan Moshonov, Yochai Maital, Podington Bear, Kevin MacLeod, Biz Baz Studio, The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Sensorama, Wayne Jones and the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra. This episode was edited by Sara Ivry, Yochai Maital and Zev Levi, and was mixed by Adam Milliner and Kfir Shai.

Thanks to Latif Nasser, Revital Iyov, Lawrence Bull, Rafi Schoffman, Dani Schoffman, Yotam Michael Yogev, Nili Priel, Chanan Mazal, Adar Waldman, Gil Messing, Noam Bar, Shira Kaplan, Israel Finkelstein, Neil Silberman, Avner Goren, Gideon and Nechama Foerster, Shlomit Bechar and Shlomo Maital for both dubbing and guiding us through the world of Israeli cybersecurity startups.

It is based on Israel Story’s latest live show tour – “The Wall.” Thanks to all who made that tour possible, including Sutton Place Synagogue, Ben Murane and Hannah Cohen from NIF Canada, Peter Fehlhaber, Lynn and Aubrey Kauffman, Elisa and Gil Palter, Brian Garrick, Mindy Shipon, Rachel LeVine, Chris Phillips and Chris Renda.

Sponsors

The Jerusalem Portfolio is a professionally managed investment portfolio of Israeli-focused public companies listed on the Tel Aviv, US and London stock exchanges. Learn more about how you can invest in the Israeli innovation, creativity and vision that made the desert bloom!

The Jerusalem Portfolio is a professionally managed investment portfolio of Israeli-focused public companies listed on the Tel Aviv, US and London stock exchanges. Learn more about how you can invest in the Israeli innovation, creativity and vision that made the desert bloom!

The first ten Israel Story listeners who sign up will receive a free $50 to invest. Use promo code ‘Israel Story’ when signing up.

Wartime Diaries

Wartime Diaries