Who is Yitzhak Rabin today, twenty years after his murder? In this episode, we discover that for many Israelis, he represents completely different – and often conflicting – things: Rachel Rabin remembers her older brother as a shy kid, who forced her to be the goalie in neighborhood soccer games. His ‘fixer,’ Me’ir Palevsky, tells how a crude joke might have saved Rabin’s political career. Aliza Goren, the woman closest to the scene of the assassination, talks about standing in the operating room, looking at a dead prime minister. For Etgar Keret, Rabin is a cat, and maybe that’s not so strange, when we hear how others – filmmakers, educators and politicians – take Rabin’s legacy in all kinds of other – no less bizarre – directions. Lastly, Naomi Chazan reads the very last note she got from Rabin – a letter from the grave.

Prologue

Host Mishy Harman reflects on his whereabouts when he received the news about the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Just about two months before November 4th, 1995, I began seventh grade. And in Israel, that’s the start of Junior High. So… new school, new building, all the other kids are new too. You have to figure out, really quickly, which group to join: The science nerds, the hippies, the Nirvana fans. You do your best to score some goals in soccer games during recess, ‘cuz that’s the surest way to become popular. Anyway, hectic times. So I was really looking forward to November 4th, it was a Saturday, because my entire old class, from sixth grade, were invited to Maya Baharal’s Bat Mitzvah. I hadn’t seen most of them since school ended the previous summer, (we had basically all gone to different Junior Highs), but it just felt familiar, and right, the minute we met up at synagogue that morning. We slipped right back into our old roles, with all the same dynamics, which had been established since kindergarten. And in that group, I was part of the cool kids. At Maya Baharal’s Bat Mitzvah, being part of the cool kids meant leading the boys to the balcony of the synagogue. There’s this tradition at Bar and Bat Mitzvahs to throw candy at the kid, once they’ve finished reading the Torah. Usually it’s soft toffee, so no one gets hurt. But Maya’s parents handed out hard candy, and I convinced the boys to play a game: We would unwrap the hard candy, lick it, throw it, and you’d get five points if you could get it to stick to the Rabbi’s bald head. I lost. I think Yonatan Yodkuvich won. Anyway, after the services we went to Sacher Park, Jerusalem’s main grassy area, and played ball. My best friend Yoav’s dad suggested that we play touch football. At sports at least, I was much more Israeli than American, so I didn’t know the rules. Everyone else did. So every time I’d catch the ball, I’d try to pass it, ‘cuz I didn’t know you had to run with it. Everyone was yelling at me. We played all afternoon, and by the time Yoav’s parents dropped me at home, I was zonked. My big brother Oren was going to Tel Aviv, for a peace rally. I wanted to go with him, but my mom said I couldn’t. I remember all of this because the next morning, really early, both of my parents woke me up. My mom was crying. My dad looked as if he hadn’t slept all night. My first thought was that my savta, my grandma, had died. But she hadn’t. My mom held my hand, and said, “Mishy, they killed Rabin.” Yitzhak Rabin was our Prime Minister. And I was obsessed with politics. I had a poster of Rabin in my room, and my favorite tshirt was one I’d gotten at an election rally, three years earlier, when Rabin won and became PrimeMinister. Yisrael Mechaka Le’Rabin, it said. Israel’s waiting for Rabin. A few years later, I was watching TV. My favorite show, HaChamishiya HaKamerit, was on. It was everyone’s favorite show at the time sort of a local SNL, with little skits about politics, and just life in general in Israel. In this particular skit, which later became really famous, there’s an MTVstyle callin show, where school children can ask questions. One girl, Ahuva, calls in and says that she’s having some trouble with an assignment she got at school. “What’s it about?” the host asks. And she says that they need to write an essay with pro and cons of the Rabin assassination. “Oh, I see,” he answers, “and you’re probably having a hard time coming up with the pros?” There’s a pause for a second, and then Ahuva replies “no, I just don’t know who Rabin is.” I guess that skit worked because at the time there was this sense, or fear, that Rabin would be forgotten. That enough time would pass that people wouldn’t even know who he was anymore. But that hasn’t happened. This week is the twentieth anniversary of that assassination, and Rabin hasn’t been forgotten. It’s more like he’s multiplied. To mean everything, and be everywhere. We thought that the best place to start was with the person who knew Rabin the longest.

Act I: Rabin is My Brother

Rachel Rabin, Yitzhak Rabin’s little sister, isn’t so little anymore. Rachel, 91, reminisces about her childhood with her older brother who she remembers as a shy kid, who forced her to be the goalie in neighborhood soccer games.

Rachel Rabin: Shalom.

Mishy Harman: Shalom, Rachel?

Rachel Rabin: Ken.

Mishy Harman: Ken Shalom, Medaber Mishy Harman.

Rachel Rabin: Ken.

Mishy Harman: Ma Shlomech?

Rachel Rabin: Beseder.

Mishy Harman (narration): Rachel Rabin, Yitzhak Rabin’s little sister, isn’t so little anymore. She’s almost 91, and she lives alone at the very edge of the country, in Kibbutz Manara, less than a hundred meters from the border with Lebanon. She had told us to call when we got to the entrance of the Kibbutz, so that she could direct us to her house. Somewhat embarrassingly, and even though there are only like two and a half streets in the whole place, we got lost. When we finally pulled into her driveway, she looked at us and with half a smile said “guys, you kind of screwed up, ha?” You wouldn’t guess her age if you saw her she has a quick step, a long white braid, and a young voice. But the main thing you notice about her, immediately, is that she looks exactly like her brother. She gave us some coffee, and slices of an apple pie she had made. We sat in her tiny apartment, and as if we were talking about yesterday Rachel took us back to the early 1930s in Tel Aviv.

Rachel Rabin: Our parents were always very busy, so we were alone a lot of the time. And somehow Yitzhak always felt that he was responsible for me. That he needed to take care of me. To protect me. And that’s how I felt. Till his last day, really, I felt he was protecting me, even from afar.

Rachel Rabin: One day, I remember, we went to see a movie. That was a big deal in those days. And I cried my eyes out. And Yitzhak, he said to me, “I’m never gonna take you to the movies again. The film’s barely started and you’re already crying. Even if it’s not sad!” So I said, “OK, I promise not to cry at the movies anymore.”

Mishy Harman (narration): Even though we know that our leaders were all just once normal kids, it’s kind of funny to imagine a national icon like Rabin going to a school dance and waiting sheepishly for some girl to smile at him.

Rachel Rabin: Yitzhak was a shy kid. Closed. Very quiet. You know, one of those ‘don’t touch me and I won’t touch you’ kind of kids. He wasn’t one of the popular, or loud, kids. But he was a good athlete, from the beginning. He was good at soccer, and his friends would come over to play soccer in the street. They didn’t want me to bother them, so they’d make me the goalie.

Mishy Harman (narration): We spent about three hours with Rachel, and I’m gonna say that I’ve never been with anyone who receives as many phone calls as she does. There were journalists, of course, old friends of Yitzhak calling to check in on her, neighbors, grandchildren, and I kid you not someone who called to say that had gone to the same summer camp as Rachel in 1935, and wanted to know whether she remembered the words to the camp anthem. She did. Before we left, Rachel took us to the den, where she keeps all her memorabilia. She pointed to the wall, to a large faded picture of their mom, Roza, holding her two kids, fiveyearold Yitzhak, in sort of a blueandwhite sailor’s outfit, and twoyearold Rachel, with short curly hair. She showed us part of a Katyusha bomb, that landed in her living room, and then she opened folders, where in individual plastic sheets she keeps dozens and dozens of letters from Yitzhak. She took out a few, and as she began reading them to us, I thought about what it’s like to share your big brother with an entire country. To have so many people feel as if they had a special relationship to him, even though they never even knew him, let alone fought with him about who would do the dishes. Rachel talks about her big brother with admiration, and respect. And from all his letters you can tell just how much he loved her too. But like all of us even with her there’s a sense that something wasn’t completely equal. In the sixties, once her brother had already become a war hero and a public figure, he was on the radio, talking about his childhood.

Rachel Rabin: My dad and I sat here in the living room and listened to the show. And Yitzhak was talking about how lonely he felt at home, growing up. And I was really surprised, since I never felt lonely. So I called him up afterwards, and we tried to understand why we had such different memories. And then I realized that I was never lonely because I had him. He was always around. And I guess I just wasn’t the same kind of rock for him as he was for me. I was just his little sister. I just miss him so much.

Mishy Harman (narration): In the years after Rachel and Yitzhak shared a small bedroom that doubled as a guest room, they went in very different directions. She established her Kibbutz in the Upper Galilee, and was a high school biology teacher till she retired. He became a soldier in the Palmach, the prestate troops. And then in 1948, in the War of Independence he was the commander of Chativat Har’el, the brigade that opened the route to Jerusalem. He quickly rose through the rank of the newlyformed IDF, till in 1964 he became its Chief of Staff. Rabin led the army to its crushing victory in the Six Day War, and was kind of a national rock star. Teenagers would ask for his autograph on the street. When he left the military, after twentyseven years, he was appointed to be Israel’s Ambassador in America, and after that he joined politics, first becoming Golda Meir’s Minister of Labor, and then, when she resigned in 1974 after the Yom Kippur War, he was named Israel’s fifth PrimeMinister. He was a different kind of politician. For starters, he was young, a member of a new generation, that hadn’t come from Europe. He was a Tzabar, born and raised here, a man of the land. But his term as PrimeMinister was anything but glorious. He was considered a mediocre leader, and in 1977 when a report came out about an illegal bank account that his wife Leah held abroad, he resigned. He lost control of the Labor party, and his big rival, Shimon Peres, was selected to run in the general elections. Peres lost, to Begin the first time the right wing Likkud party came to power. So, at the age of fiftyfive, Rabin had basically become a has been. He wasn’t very popular anymore, just kind of living a normal life. That’s where our next story picks up.

Act II: Rabin is Just a Guy

Yitzhak Rabin’s ‘fixer,’ Me’ir Palevsky, tells how a crude joke might have saved Rabin’s political career.

Me’ir Palevsky: We used to eat in restaurants. You had hummus and kebab, and that’s all. No lobster, no shrimps, no… no… like the others. Hummus and kebab, and that’s all. And some whisky. More than some whisky.

Mishy Harman (narration): Me’ir Palevsky is a private detective. He lives alone, in Tel Aviv. He smokes a lot, writes a lot of facebook statuses. Me’ir and Rabin had a very special relationship. They were friends, but not only: Me’ir doesn’t like the term, but he was Rabin’s fixer. The guy that takes care of things, things that a politician needs, but can’t really know about. They met after Rabin had resigned the Prime Ministership.

Me’ir Palevsky: It was the end of the 70s. We were in the reserve in the army in the Sinai desert, reserve soldiers. Ordinary people. Like me, I’m not ordinary, but everybody is ordinary. Begin was the Prime Minister then. And we were not happy about what was going on in the country. We discussed the situation and decided we needed another Prime Minister and we decided between us that Rabin was the right person and could make it better. So, we went home after the reserve. We found his phone number in the book, his private number in his apartment. We called it, made an appointment. We came to the office. His handshake was very shaky. He was a general in the army and so on but he was not a macho. He was like a university lecturer or something like that. He didn’t look me in the eyes, he looked down. His friend goes, “What can I do for you?” I said, I want you to be the Prime Minister. He sat back, was a little bit startled. You need to understand at the time, Rabin was at the back benches of the party. Nobody cared about him. He was alone. Nobody cared about him except us. We kept talking about the idea. He didn’t commit but he was interested. We decided that at the end of the meeting, we will make a gathering at my home with 40, 50, 60 people. We will talk to them and see the atmosphere. We were sitting, a lot of people in my apartment. 60 people, sitting on the floor. Everywhere. Rabin was sitting on the chair like this and I was beside him. And he started telling us memories at the time when he was the Prime Minister. The finance minister came to him with the problem of inflation and suddenly the unions of the teacher began striking and in the middle of all this mess, the Prime Minister of Canada Trudeau came to Israel. It was a boring lecture. It was so boring that everybody started moving. So one of my friends asked him, did Trudeau brought his wife? His wife was a famous beautiful woman and the gossip said she had a fling/romance with Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones. “Yes, sure” he said. “How is the wife?” He said, in English, “Nothing to write home about.” She was a famously beautiful woman. So my friend insisted, said, “Everybody is saying she is beautiful.” He didn’t answer. People started moving. Didn’t like the atmosphere. The evening was going very wrong. I was not happy so I decided, I must make a move to salvage this evening. if my fail, I fail, if I succeed, we all succeed. so I open my mouth, I have a big mouth. I said, “yitzhak” you never call him Yitzhak. Respectfully, “Yitzhak”. So I said loudly and clearly, “Yitzhak.”…I’m trying to translate..I’m trying to find the words…Okay, I said…. “Yitzhak, would you fuck her?” Everybody starts laughing and his wife, she sent me her rays of fire from her eyes. He didn’t answer but he became free because he was 40 years in the army. You know the nature of people in the army. So the atmosphere became very friendly. And the evening became a big success. Everybody was very happy and joined our Rabin group and the rest is history. The end of the evening, him and his wife stayed with me and my wife with some whiskey he said in his voice, “Meir, don’t do it again.” And I said, “Yitzhak you started!”

Mishy Harman (narration): Ultimately, whether or not that exchange about Trudeau’s wife actually served as a pivotal moment, Rabin’s career got back on track. There was a national unity government and Rabin served as the Defense Minister. These were the days of the first Intifada, the popular Palestinian uprising, and Rabin was a hardliner. He famously said that Israeli soldiers shouldn’t shoot at the Palestinian protestors and stone throwers, but should break their arms and legs. He was Mr. Security, and in 1992, he finally beat his nemesis, Peres, in the Labor Party primaries. In June of that year, he led the Labor Party to a resounding victory in the general elections, in a campaign which mainly emphasized his personal popularity. That’s when I got that “Israel is waiting for Rabin” tshirt. The night of his election, at least in my house, there was a lot of excitement. Almost immediately Rabin set off on a new path. It included negotiations with the PLO, and their leader, Yasser Arafat. These were the Oslo Accords, which recognized the PLO and granted the Palestinian Authority partial control in Gaza and certain cities in the West Bank. On September 13, 1993 I remember listening to the radio, with my mom in the car, when Rabin somewhat reluctantly shook Arafat’s hand on the South Lawn of the White House. My mom looked at me, with tears of disbelief in her eyes, and said, “remember this moment, Mishy.” The next year, we made peace with King Hussein of Jordan, and Rabin, Peres and Arafat flew to Oslo to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. People were talking about a peace treaty with Syria, and there was this general sense of hope in the air. We could actually end this bloody struggle. Of course not everyone shared those feelings. Terror attacks continued, and the right blamed Rabin, saying that his agreements gave the Palestinians guns, which were now being used to kill Israelis. He was giving away the land, they claimed, and before long the more extreme voices began calling Rabin a traitor, a murderer. There were rabbis in the West Bank who performed Pulsa DeNora ceremonies against Rabin, basically kind of a ritual curse. Some said outright that he should be killed, and the demonstrations got more and more hateful. In one big rally, in Jerusalem’s Zion Square, on October 5, 1995, the political leadership of the right, including Bibi Netanyahu, Ariel Sharon and many others, gave speeches from a balcony. Below them, the demonstrators handed out leaflets with a picture of Rabin dressed in an SS uniform. Dead doves were sent to Rabin’s office, even to his home. Some youngsters vandalized his car, and one religious man tried to assault him at the end of an event he attended. As all this violent rhetoric escalated, the left began planning a counterdemonstration, which would take place a month later, in Tel Aviv’s main square. The slogan for the rally was Ken LaShalom, Lo La’Alimut Yes to Peace, No to Violence. The organizers didn’t know how many people would show up, and Rabin was nervous. The elections were less than a year away, and he needed a strong showing of support to continue with his peace making policies. People we talked to told us that Rabin himself sent them to scout out the square, and report back every hour how many people were coming. If it was just a few thousand, he thought, he might say he came down with a sore throat. But there was no need for excuses. The square was packed. Rabin spoke, a speech which has since become part of Israeli history, about how violence eats away at the foundations of democracy. He said that that wasn’t our way. We solved things in democratic elections, not by violence. At the end of the rally the leadership of the left stood together and sang Rabin couldn’t carry a tune a song called, Shir LaShalom, A Song for Peace. Everyone felt exhilarated. Including Rabin. It had been a big success. Then he walked down the stairs, to his car. That’s where Yigal Amir, the assassin, was waiting.

Act III: Rabin is Dead

Like the JFK assassination, everyone remembers what they were doing when they heard the news. For Aliza Goren, that isn’t so hard – she was one of the people closest to the news. Matan Dishon, on the other hand, was more or less the farthest you could get from the news, at least in Israel.

Mishy Harman (narration): Like the JFK assassination, everyone remembers what they were doing when they heard the news. For Aliza Goren, that isn’t so hard she was one of the people closest to the news.

Aliza Goren: My name is Aliza Goren, and I am a businesswoman. I was used to be the spokeswoman for PrimeMinister, the late Prime-Minister Rabin, until the minute he died.

Mishy Harman (narration): Matan Dishon, on the other hand, was more or less the farthest you could get from the news, at least in Israel.

Matan Dishon: My name is Matan. Dishon. I live in Kibbutz Mizra, in Jezreel Valley. Twenty years ago we were serving in a post in Lebanon, in the Security Zone. My unit is called Palch”an Nachal which is like a small unit, who is professionally suited for handling engineering and explosives.

Mishy Harman (narration): Together, they tell the story of that night, November 4th, 1995.

Matan Dishon: So that night it was winter of course and it was probably cold and muddy as usual.

Aliza Goren: That night, we had a big rally in Tel Aviv. And Rabin wasn’t sure he wants to do it. And he had to be convinced.

Matan Dishon: We were doing this mission called a stake out. Marav Beten. Marav Beten: Marav is a stake out and Beten is like belly. Probably around ten or so, soldiers just lie on your belly all through the night in the mud and watch over whatever.

Aliza Goren: The place was full of people. There were about a quarter of a million people at that rally. Very big demonstration in Israel and they were all carrying signs supporting him, supporting his acts, supporting peace. It was so nice and Rabin was so happy and at the end of it, they sang the song of peace.

Matan Dishon: That part of Lebanon is really beautiful. Quite high mountains, they are green I guess most of the year. Rivers running below this ridge for instance. And there’s quite nice cliffs, it’s a really nice place to be in terms of the wilderness, the view. But there wasn’t even one second that you can forget that it’s really dangerous.

Aliza Goren: We start to say goodbye to everybody and I escorted him to the car. We went downstairs, the car was waiting for him. The bodyguard was walking behind him. There were a lot of policemen around him. I was walking behind the bodyguard and he kept saying goodbye to people while stepping down the stairs, and suddenly I heard shots.

Matan Dishon: And suddenly, we see, as far as the eye can see, flares, shootings, we hear a lot of gunshots in the air. And these light flares.

Aliza Goren: Now, I’ve never heard shots before. I’ve never witnessed a scenery like this. And I saw that he fell and in a minute it was, the car was vanished. They drove off, they threw him into the car and they drove off. And I was standing there and I couldn’t..I kept thinking “what happened?”

Matan Dishon: So, I think my initial thought was that the stake out was discovered and we’re under some kind of attack. Because you hear gunshots and see all these flares in the air. And then the next thought was that it was very widespread across Lebanon. It’s all of Nabatieh and all of the villages around shooting in the air and these flares and fireworks and so on. So, it’s probably not about us, but something is happening.

Aliza Goren: Then I saw a pile of people laying one on top of the other, and on the bottom was Yigal Amir, the murderer. A filthy murder.

Matan Dishon: I believe I thought it was some kind of celebration, some kind of Lebanese holiday or celebration, something like that.

Aliza Goren: I was standing there and I said “what am I going to do? I have to call and see where he went, Rabin, and if something happened to him.” The only number I could remember at this moment was the number of the military attache of Rabin, Dani Atun. So I called him up.

Matan Dishon: And then we radioed up back to the post, what’s going on?

Aliza Goren: And I said listen Dani, I think they shot Rabin. He said, “what are you talking about?” In the beginning he was yelling at me that I’m imagining things. And I said, “listen, they shot him and I have to know where he went.” He said, “I’ll get back to you in a minute.”

Matan Dishon: And then the reaction was quite surprising, something we didn’t hear anywhere before, saying something like, in Hebrew it’s “kodkod kahol lavan eneno,” the blue and white vertex is gone. So I have to explain that sentence probably. Blue and white is a code the radio code for Israel. Vertex is a general radio code for an officer.

Aliza Goren: He got back to me in a few minutes and said, “they took him to Ichilov hospital.” Which was like a mile, a mile and half away. But my car was parked so far so I started running by foot. At some point, my assistant drove next to me and drove me the rest of the way.

Matan Dishon: We dismantled this stake out, we went back to the post..very early. I guess I started thinking about who is gone? Who is this person who is gone and what’s all these celebrations?

Aliza Goren: When I got there, I went downstairs, I saw Mrs. Rabin with the driver. And he told me, the driver told me, “Listen, they shot him in the back and he was wounded.” And I said, “What are you, a doctor?” and she was standing there speechless, Leah Rabin. We went downstairs…where the operation rooms were and oh we waiting I think about an hour and a half, two hours.

Matan Dishon: I guess we were very alert because of all these shootings and flares. I also guessed that we were maybe a little bit happy to go back to the posts instead of spending the night on our bellies in the mud. So, I believe that was our state of mind at that point.

Aliza Goren: While waiting, people started gathering there, all of the cabinet members, some of the security forces, the chief of staff. And then, ? general of the hospital came out and said, “I’m sorry but he died.” And we couldn’t believe it.

Matan Dishon: Guessing that Rabin was dead, killed, assassinated, that of course, was out of anyone’s imagination at that point. But we found out that our prime minister was assassinated and we were of course shocked. But I must say that the missions in the post, were overwhelming even on this event.

Aliza Goren: A few people, his wife, his kids, Shimon Peres, another cabinet member by the name Efraim Sneh, Dani Atun, the military attache, maybe another person, I don’t remember, went to see the body and he was lying there covered with a sheet. And he had a bruise on his forehead because he fell. He was lying there so calm. It was terrible, really terrible. Everyone went and kissed his forehead. I was just standing there, I couldn’t touch him. I just.. I was the only one who didn’t touch him and didn’t kiss his forehead. I just stood there, looked at him. That’s it.

Matan Dishon: When we came back to Israel after about four weeks, we really realized what happened and could really stop and think about it. And then it was..it felt like a backstabbing.

Aliza Goren: I thought it was the end of Israel. That Israel will never be able to get back to what it was. That evil has prevailed. That injustice has prevailed. The incitement succeeded in an undemocratic way and I think it’s..we still feel it until today.

Mishy Harman (narration): That piece was by Shoshi Shmuluvitz, with original music from Collin Oldham. Etgar Keret, an author and a regular contributor to our show, lives less than a ten minute walk from Kikar Malchey Israel, the square where Rabin was murdered. One of his most iconic short stories is actually about Rabin. Yochai Maital and I went to talk to him about that story. It’s called “Rabin is Dead” but Rabin in the title of the story isn’t the Rabin.

Act IV: Rabin is a Cat

Etgar Keret, an author and a regular contributor to our show, lives less than a ten minute walk from Kikar Malchey Israel, the square where Rabin was murdered. One of his most iconic short stories is actually about Rabin. It’s called “Rabin is Dead” but the Rabin in the title of the story isn’t THE Rabin.

Act TranscriptEtgar Keret: I got a lot of bad reactions. kind of people said how dare you write a story about a cat named rabin? you know? this means that you really didn’t like rabin that you didn’t believe in the peace process. that you hate your own country. and the world thinks that calling a geriatric hospital in which people pee on himself, rabin hospital, is very respectable, or calling a dead end street that is all dirty rabin street is wonderful, but calling the animal that they love the most after rabin, is something that is not acceptable. so this is kind of how I sat down and started writing this story.

Mishy Harman (narration): Here’s Etgar’s story, read to us by Neil Friedlander. Rabin’s dead. It happened last night. He got run over by a scooter with a sidecar. Rabin died on the spot. The guy on the scooter got hurt real bad and passed out, and they took him away in an ambulance. They didn’t even touch Rabin. He was so dead, there was nothing they could do. So me and Tiran picked him up and buried him in my backyard. I cried after that, and Tiran lit up and told me to stop crying cause I was getting on his nerves. But I didn’t stop, and pretty soon he started crying too. because I really loved Rabin a lot, but Tiran loved him even more. Then we went to Tiran’s house, and there was a cop on the front stairs waiting to bag him, because the guy on the scooter came to and squealed to the doctors at the hospital. He told them Tiran had bashed his helmet in with a crowbar. The cop asked Tiran why he was crying and Tiran said, “Who’s crying, you fascist motherfucking pig.” The cop smacked him once, and Tiran’s father came out and wanted to take down the cop’s name and stuff, but the cop wouldn’t tell him, and in less than five minutes, there must’ve been like thirty neighbors standing there. The cop told them to take it easy, and they told him to take it easy himself. There was a lot of shoving, and it looked like someone was going to clobbered again. Finally the cop left, and Tiran’s dad sat us both down in their living room and gave us some Sprite. He told Tiran to tell him what happened and to make it quick, before the cop returned with backup. So Tiran told him he’s hit someone with a crowbar but that it was someone who had it coming, and that the guy’d squealed to the police. Tiran’s dad asked what exactly he had it coming for, and I could see right away that he was pissed off. So I told him it was the guy on the scooter that started it, ‘cause first he ran Rabin over with his sidecar, then he called us names and then he went and slapped me too. Tiran’s dad asked him if it was true, and Tiran didn’t answer but he nodded. I could tell that he was dying for a cigarette but he was afraid to smoke next to his dad. We found Rabin in the square. Soon as we got off the bus we spotted him. He was just a kitten then and he was so cold he was trembling. Me and Tiran and this uptown girl with a navel stud that we met there, we went to get him some milk. But at Espresso Bar they wouldn’t give us any. And at Burger Ranch, they didn’t have milk ‘cause they’re a meat place and they’re kosher, so they don’t sell dairy stuff. Finally, at the grocery store on Frishman Street they gave us a halfpint and an empty yogurt cup, and we poured him some milk, and he lapped it up in one go. And Avishagthat was the name of the girl with the studsaid we ought to call him Shalom, because shalom means peace and we’d found him right in the square where Rabin died for peace. Tiran nodded and asked her for her phone number, and she told him he was really cute but that she had a boyfriend in the army. After she left, Tiran patted the kitten and said that we’d never in a million years call him Shalom, because Shalom is a sissy name. He said we’d call him Rabin, and that the broad and her boyfriend in the army could go fuck themselves for all he cared, cause maybe she had a pretty face but her body was really weird. Tiran’s dad told Tiran it was lucky he was still a minor, but even that might not do him much good this time, because bashing people with a crowbar isn’t like stealing chewing gum from a candy store. Tiran still didn’t say anything, and I could tell he was about to start crying again. So I told Tiran’s dad that it was all my fault, because when Rabin was run over, I was the one who yelled it to Tiran. And the guy on the scooter, who was kind of nice at first and even seemed sorry about what he’d done, asked me what I was screaming for. And it was only when I told him that the cat’s name was Rabin that he lost his cool and slapped me. And Tiran told his dad: “First, the shit doesn’t stop at the stop sign, then he runs over our cat, and after all that he goes and slaps Sinai. What did you expect me to do? Let him get away with it?” And Tiran’s dad didn’t answer. He lit a cigarette, and without making a big deal about it, lit one for Tiran too. And Tiran’s dad didn’t answer. And Tiran said the best thing I could do would be to beat it, before the cops came back, so that at least one of us would stay out of it. I told him to lay off, but his dad insisted. Before I went upstairs, I stopped for a minute at Rabin’s grave and thought about what would have happened if we hadn’t found him. About what his life would have been like then. Maybe he’d have frozen to death, but probably someone else would have found him and taken him home, and then he wouldn’t have been run over. Everything in life is just luck. Even the original Rabin after everyone sang the Hymn to Peace at the big rally in the square, if instead of going down those stairs he’d hung around a little longer, he’d still be alive. And they would have shot Peres instead. At least that’s what they said on TV. Or else, if the broad in the square wouldn’t have had that boyfriend in the army and she’d given Tiran her phone number and we’d called Rabin Shalom, then he would have been run over anyway, but at least nobody would have gotten clobbered.

Mishy Harman: I’m constantly thinking is there an allegory here that I’m not getting?

Etgar Keret: I didn’t write it as an allegory, and I think that the thing that connected me the most to this kind of collective emotion that I felt in Israel after the assassination of Rabin was this idea that everybody was in pain, and everybody was really really sad, but a lot of the people instead of showing this sadness or vulnerability they turned into some kind of aggression. I think there is something about Israeli mentality that whenever you have pain or vulnerability then you automatically try to transform it to something that is more macho like, or more kind of defendable, which in this case would be to take your anger out on somebody. When I wrote the story, I wanted to write a story about some kind of ritual of memory, but i think that what came out of it was really this kind of inability to show your pain, and how this inability to share your pain turns pain into aggression.

Yochai Maital (narration): This aggression was something that Etgart witnessed personally, on the very night of the assassination.

Etgar Keret: When Rabin was assassinated, I was watching with a friend a trashy film on TV, and we were really bored. one of us his girlfriend dumped him, and i remember that we were really really depressed that day anyway, and the movie was really really bad, we just saw it because it was kind of pre cable time so it was the only thing you could see on tv, and then they stopped showing the film and started talking that something happened in the square, and my friend said i must have a drink. so we turned off the TV and we went outside of his house. there was a pub in lasalle street which is now closed, it doesn’t exist anymore, and we went there and they were closing the place because of Rabin’s assassination. and he said just give me a beer for the way, my friend. and the guy said to him I can’t sell you beer, Rabin was assassinated. so my friend said i want to have a beer to mourn for him, i want to drink a beer in his memory. and the bartender said you shiting with me? and he said no you shiting with me, and like in twenty seconds, they almost had a fight. they almost had a punch fight. and you felt that both of them were very very volatile but their emotion turned into some kind of anger toward the world and i remember myself in lasalle street both of them kind of trying to punch each other and me pushing them to two sides and both of them were much bigger than me. so this is kind of my memory. this kind of eruption of violence that nothing to do with reality. I never saw my friend get into a fight, you know. i hardly see people in tel aviv get into fights, and this kind of fight that i thought all came from this kind of pain, and anger, that had to be ventilated somewhere, and me there kind of trying to stop it in a very unsuccessful way.

Yochai Maital (narration): And how is etgar going to mark the 20th anniversary of rabin’s assassination?

Etgar Keret: Well, the truth is I don’t give much importance to specific dates, but the issue of Rabin’s assassination is something that comes up in my conversations with my son, and actually my son had told me and my wife during the last Gaza war that we should learn from this countries history and not say out loud that we want to have peace. because he said that if i quote him ‘if you would have listen in school, then you would have known that Rabin and saadat and john lennon were all killed because they wanted peace, and I want peace to, but even more than that I want to have parents so… you can support peace but you shouldn’t say that in public places. that’s the lesson that he got from Rabin’s assassination.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yochai Maital. So, if for Etgar, Rabin could be a cat, for other Israelis, especially in recent years, Rabin can take on almost any shape or form.

Act V: Rabin is Up For Grabs

For Israelis, especially in recent years, Rabin can take on almost any shape or form. Shai Satran speaks to filmmakers, educators and politicians about their take on Rabin’s legacy.

Act TranscriptShai Satran (narration): There was this moment toward the end of the 2015 election debate. It was a small moment but I just can’t get it out of my head. Naftali Bennett, the leader of Israel’s nationalist right wing party, and Zehava Galon, the leader of the leftist party were going at it. They were arguing about the two state solution, and the settlements. She called him a fascist. and then this happened: Bennet says: for 20 years the left has held Rabin’s murder over Bibi’s head. I’m not part of that generation he says, I’m part of a generation that doesn’t apologize! I am not going to apologize for that! The reason this is such an amazing moment is that until that point, in an hour and a half debate, no one even mentioned Rabin’s name. In a sense, Bennett just brought Rabin up out of the blue. But the truth is, over the last twenty years Rabin is always there, just under the surface of any political argument, any talk of Palestinians, settlements or terror. A few moments later Bennett was at it again: I’ll tell you where I was when Rabin was murdered, during that same murder which you’re blaming me for: I was an officer in combat in the south of Lebanon protecting you! and you won’t dare accuse me of the murder! I am proud of my opinions! Zahava Galon tries to counter I didn’t blame you of the murder she says. and she didn’t. but also, in a sense, she did… Rabin was murdered by a religious right wing Jew. In the weeks and months before the murder there was an escalating atmosphere of incitement against Rabin, seen as stemming from, or at the very least allowed by, the right wing and religious leadership. Netanyahu, who was then the head of the opposition, was one of those held responsible. Dror Moreh is the director of the academyaward nominated documentary ‘The Gatekeepers.’ He spends a lot of time thinking about that day, November 4, 1995.

Dror Moreh: The assassination of Rabin marked the lowest point, which from there we are only going down.

Shai Satran (narration): He’s outraged at the reality which has allowed Bibi, just two decades later, to become the chief eulogizer at Rabin’s memorials.

Dror Moreh: Bibi walked in a rally where behind him there was a coffin, and on that coffin it said, Rabin, the killing of the Zionism. What does it signal? He was sitting or he was standing on the porch in those horrible demonstrations that were in Jerusalem in the Zion square, where Rabin was portrayed as a nazi SS officer …so the political leadership…. people that are with us still in the Knesset today.

Shai Satran (narration): Talking to Dror a picture of Rabin and the murder emerges: Rabin was courageous in fighting for peace. The extreme right and the religious zealots were responsible for creating the national atmosphere in which the murder could occur.

Dror Moreh: Rabin was the Prime Minister of Israel. He was assassinated because he tried to go for peace. The commemoration of Rabin is subdued into one camp which is shrinking rapidly which is the “peace camp” let’s call it like that, in Israel. And the other camp is growing bigger and stronger.

Shai Satran (narration): This is a widespread sentiment in the Israeli left: We are the few that still uphold Rabin’s memory, they say. And while it is undoubtedly true that sizeable parts of Israeli society would rather forget Rabin altogether, it isn’t that simple.

Erez Eshel: You know you try to say I belong to his legacy. Okay..so say it.

Shai Satran (narration): This is Erez Eshel. As you can hear, Erez has strong feelings concerning Rabin.

Erez Eshel: He was from the labor so what? so what? Because Rabin doesn’t belong to the left. He was the Prime Minister of the state of Israel of the Jewish people around all of the world and we so many times get confused. Thinking that he belongs to one group.

Shai Satran (narration): Erez is a right wing religious educator, though he probably wouldn’t like me labeling him as such. He is the founder of several prearmy leadership academies. Like Dror, he considers the murder to be the defining moment of his life, and a watershed moment in Israel’s history. But the similarities end there: Erez’s Rabin is rather different than Dror’s.

Erez Eshel: For me Rabin is a warrior that sacrificed his life in the Independence War. For me, Rabin is the one that symbolizes uniting Jerusalem. The Six Day War. I am a real Zionist. I will give my life for the State of Israel, for the Land of Israel and for the People of Israel. I do believe in all of the Land of Israel. I do. I believe the Yitzhak Rabin believed in all of the Land of Israel.

Shai Satran (narration): And how does Rabin’s striving of peace factor in?

Erez Eshel: You know, there was the endless campaign about peace. Many times the campaign for the peace was a campaign against the extremers. Against the settlers. This fantasy, saying like ‘if Rabin would be alive, we would have peace now.’ And there were no stabbing and no explosions Peace movement! With whom do we do peace? We speak about in Gaza Hamas? In the West Bank-Abu Mazen?

Shai Satran (Narration): Many people in the nonextreme right agree with Erez: They think that the peace process has tainted Rabin’s true legacy. Rabin is remembered as a military hero and the unifier of Jerusalem. In this narrative the peace process becomes a late-life lapse of judgement, of which we need not be reminded too often. In addition, the tendency to scrutinize the murderer’s religious and political background is considered misguided.

Erez Eshel: Yigal is nothing for me. He’s really nothing for me. The blame of the murder of a symbol, of a Prime Minister, is a blame of all the groups of the Israeli society. There was a lost of trust between left and right, secular and religious, we lost the respect.

Shai Satran (narration): This is a major point of disagreement. For Dror the murderer is instrumental.

Dror Moreh: Not only that he succeeded in assassinating the Prime Minister and by that the assassinating the peace process, he succeeded also because of this false kind of unity that was swept over Israel after the assassination. And to call Yigal Amir as a weed…as ….to isolate him as someone that was instead of really looking at the bigger picture and looking at the camp that he came from. He represents thousands of thousands of people in that camp, and today I think it’s in the tens of thousands of people. And in that sense, we failed.

Shai Satran (narration): This kind of exchange over Rabin’s identity, the responsibility for his murder and the lessons from the murder, has been happening, in one way or another, for the past twenty years. But it hasn’t been happening in a vacuum: Today the peace process seems all but dead, Israel’s politics have shifted to the right, and the left, or “the peace camp” as Dror called it, has indeed shrunk considerably. Some of the ways in which Rabin is routinely discussed today would have seemed unacceptable ten or fifteen years ago. Around this time of year there is always a lot of talk of Rabin’s legacy. It’s become a phrase, almost a cliche. In Israel there are oped pieces in every paper with titles like “Rabin’s real legacy,” or “In Search of Rabin’s Legacy.” The findings are dizzying in their variety. Some say his legacy is dialogue, or pragmatism. Others make it about his personality traits honesty, responsibility, humility. Prime Minister Netanyahu seems to find in Rabin inspiration for whatever necessary. Last year, speaking at the annual memorial ceremony for Rabin, Bibi talked about the Iranian threat, crediting Rabin as a leader who recognized the dangers of a nuclear Iran. I figured it was worth paying a visit to the official bearer of Rabin’s legacy. A law was passed in 1997, establishing the Rabin center in Tel Aviv as the official commemoration center for Rabin and the murder.

Annie: My name is Annie Eisen. I handle international relations for the center.

Shai Satran (narration): The Rabin center is in a delicate position in the midst of Rabin’s commemoration. Right off the bat Annie made it clear that the center is government funded, not political and that they tell the “full story.” The full story tries to be all inclusive. You can find Dror’s Rabin here the Rabin who went for peace. And Erez’s militarized Rabin? He’s here too. There is definitely an attempt to keep Rabin appealing in the current zeitgeist.

Annie: I don’t agree that he was a leftist, I think he was a pragmatic strong leader, I’m not saying he was a rightist, I’m saying he was a centrist and he was a pragmatic human being. I think we are doing him a disservice if we label him.

Shai Satran (narration): I asked Annie if by not labeling Rabin we aren’t allowing people to exploit him for their own political agendas.

Annie: Rabin’s legacy is transcending all of that, he is becoming more in consensus for the left and for the right.. I think it’s wonderful that so many people feel inspired. i think 20 years on his legacy is more powerful than ever, because people understand what a courageous leader he was, that he was able to understand like, this is it, we don’t have a choice, and if all these different people from different parts of society can tap into Rabin and understand his greatness, WOW that’s amazing, isn’t it?

Shai Satran (narration): So, there we are, twenty years after the murder: Rabin’s a courageous military leader. A great guy. A leftist, a hawk, a centrist. A reminder that violence is bad, that democracy is important, and that we should all just get along. Maybe this diluted, compromised, onesizefitsall version of Rabin’s legacy is all we as a society can handle at the moment. So be it.

Mishy Harman (narration): Shai Satran. It used to be taboo, at least in most circles, to utter anything but total condemnation of the assassin, Yigal Amir. No longer. Just this week the Jerusalem soccer team, Beitar Yerushalayim, was punished because its fans were chanting slogans praising him. The last person we talked for this show lives right next to the stadium, and can hear those hateful chants in her living room.

Act VI: Rabin is Really Gone

Naomi Chazan, a former member of Knesset (and Mishy’s aunt), reads the very last note she got from Rabin – a letter from the grave.

Naomi Chazan: My name is Naomi Chazan, I’m a professor of political science, and a former Member of Knesset. I was Deputy Speaker of the Knesset for quite some time.

Mishy Harman: And my aunt.

Naomi Chazan: And your aunt, of course, maybe I should have said that first.

Mishy Harman (narration): Naomi is one of the leaders of the Israeli left. She was first elected to the Parliament as part of the Meretz Party in 1992, when Rabin won the elections and became Prime Minister. She was a member of his coalition, and was there, at the demonstration, the night he was killed.

Naomi Chazan: Of course I was at the rally! That was a period when we were at rallies of one form or another several times a week.

Mishy Harman (narration): Naomi left a bit early, right after Rabin spoke, so that she’d beat the traffic. By the time she got to Jerusalem she had heard the news on the radio. But the words of that speech weren’t the last ones she heard from Rabin.

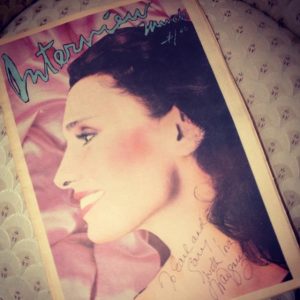

Naomi Chazan: Exactly two weeks later, a messenger came with a package. Small package. From the the Prime Minister’s office. And I opened it.

Mishy Harman (narration): Inside was a book, and two letters. The first was written by Eitan Haber, Rabin’s Chief-of-Staff.

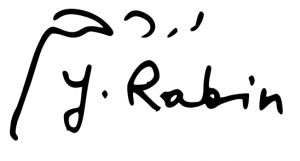

Naomi Chazan: Dear Naomi, even after the tragic events, I thought you’d want to receive this on your birthday, it was my birthday. And here is a letter and a book that Yitzhak wrote you, wanted you to have. And he prepared it before he was assassinated. And I opened further, and found a letter, a birthday greeting, from Rabin. The letters was dated, 18 November, 1995. Signed by Rabin.

Mishy Harman: So two weeks after he was murdered.

Naomi Chazan: Exactly two weeks after. And I must admit it sent chills down my spine. And the truth of the matter is even when I talk about it, (I talk about it rarely)… But still… It’s sort of… It’s chilling, it’s amazing. That was my gift from Rabin, in sense a present from somebody who had died, and been assassinated, for what he believed in.

Mishy Harman: Sort of a letter from the grave?

Naomi Chazan: Exactly, yeah.

Mishy Harman: Can you show that to me?

Naomi Chazan: Sure! To Naomi, greetings. Your birthday is a day of celebration for all of us. Please receive my greetings for health and longevity. Mazal tov, congratulations, Yitzhak Rabin.

Mishy Harman: What do you… What does it do to you? What do you feel reading this?

Naomi Chazan: Oh… Jesus.. I haven’t… Truth be told I haven’t read it out loud, I never read it out loud until today. But you Mishy have seen it several times because you… Every time you come visit me you go to it, like a magnet.

Mishy Harman: But what does it make you feel?

Naomi Chazan: Ehh, sad, reflect[ive]. It makes me feel like part of the Israel that I knew and loved is no longer here.

Mishy Harman (narration): But what is here, Naomi believes, is a deep deep concern.

Naomi Chazan: Israel’s democracy has never been the same since the assassination of Rabin. In the twenty years that have elapsed, no one has had the courage that Rabin had to pursue peace. In many respects peace has almost become a dirty word. And I would go one step further: The fundamental source of Israel’s strength is its democracy, and if it undermines its basic democracy, then it’s in trouble. I don’t love Israel any less, maybe even more, but the challenges are much greater in the past twenty years than they have been, or were, at the time.

Mishy Harman (narration): That piece of music that you’re hearing, that’s Bach’s Mass in B Minor. But, for, I’m gonna say almost every Israeli over thirty, it’s the Rabin song. It accompanied every broadcast surrounding his death, and every anniversary ever since. And it takes me right back to seventh grade. To a feeling of loss, and pain, and confusion. There’s something visceral about it, for me, and raw, in that way that music, or smells, can put you back in an exact moment in time. This week I went to the big memorial rally for Rabin, in the same square where he was killed, twenty years ago. I’ve been going almost every year, but this time it felt different. There wasn’t really anything emotional or painful about it. Bill Clinton spoke beautifully, Rubi Rivlin, our President, also said some nice things. But I was looking around, and most of the crowd kids from youth movements spanning the political and religious spectrum were sort of having a good time. It was a happening. They hadn’t been born when Rabin was murdered, and I can’t blame them it’s hard to get all emotional about a historical figure. I mean how many people cry at Lincoln memorials these days? But for me Rabin, and his memory, go together with sitting on sidewalks, lighting yahrzeit candles and singing sad songs into the night with people you don’t know. And I guess that’s what time does. Maybe that satire program wasn’t so wrong after all. Rabin hasn’t been forgotten, but he’s remembered in so many different, even conflicting ways, that they kind of cancel each other out. And maybe, in his case, that’s what being forgotten really means.

Credits

This episode was a mammoth effort, by the entire Israel Story team, and orchestrated by Shai Satran. Thanks to Davia Nelson, of the phenomenal Kitchen Sisters, who dubbed Rachel Rabin, to Niva Lanir, Uri Rosenwaks, Dani Zamir, David Harman, Matti Friedman, Rotem from the Rabin Center, Guy Eckstein, Elad Stavi, and Yonatan Glicksberg. To Collin Oldham for the original music for Rabin Is Dead, and to the IDC Radio Studios in Hertzliya. Our staff includes Yochai Maital, Shai Satran, Roee Gilron, Maya Kosover, Benny Becker and Shoshi Shmuluvitz. Rachel Fisher and Sophie Schor are our incredible production interns. Julie Subrin’s our Executive Producer.

Wartime Diaries

Wartime Diaries