In the last episode of Israel Story, we met couples in love. But for every story of love found, there are, of course, piles and piles of broken hearts. So today on our show, “Over and Out.” We’ve got three stories of relationships that have ended, and the things (the often slightly nutty things) that people do once they no longer see eye to eye. We’ll journey back to the early days of the State of Israel, and then travel all around the world, to London, New York, and even to Beijing.

Our first story, “United We Fall,” chronicles the falling apart of a tight-knit ‘family’ – the members of Kibbutz Ein-Harod, in the north of Israel. It was founded in 1921, and three decades later – in 1952 – things started to disintegrate. After years of living, farming, and fighting together, they found themselves on opposite sides of a deep ideological rift. The sense of hurt that accompanied that breakup hasn’t fully healed to this very day.

Act TranscriptYisrael Smilanski: The story of EinHarod, the split, the pilug, was very sad story, it was a break of lot of years of friendship and all of a sudden the whole thing fall apart. .ר חל לצטר: הלכו פה מכות. היו פה דברים נוראיים .פ ה היתה דרמה אמיתית. ומשפחות רבו בינהםVoiceover: there were fistfights here. actual fistfights. terrible things. a real drama, which tore apart families.

Muki Tzur: Big friendships that were completely destroyed.

Yisrael Smilanski: The fight here, was like a war. Really war.

Yochai Maital (narration): Once upon a time, there was a small kibbutz in the north of Israel called EinHarod. It was founded in 1921, by chalutzim, or pioneers, who came from Russia.

Yisrael Smilanski: EinHarod was the first kibbutz to be in this place, in the eastern side of Emek Yizrael Jezreel Valley.

Yochai Maital (narration): The kibbutz was built on top of a hill covered with wildflowers. Right below it was a wide valley with green fields, and in the distance the Gilboa Mountain where King Saul and his son Jonathan were slain in the biblical battle with the Philistines towered above it all. The Jordan River snaked to the east, and beyond it, on clear days, you could make out the imposing hills of the Gilead. The members of Ein Harod weren’t each other’s’ neighbors. They were family. They lived a completely communal life tilling the land together, going out to the battlefield together, raising their children together. Three times a day they would gather in the cheder ochel the dining hall for communal meals, and, on Fridays, they’d mark the end of the work week with some singing, dancing, and a drop of cheap brandy. This serene idealism went on for more than thirty year. But then one day, in 1952, it all came to an abrupt end. To understand the rift that tore apart this tightknit community, and changed it forever, we need to go back to the early days of the state: Though they never represented a large segment of the population, kibbutzim were the golden boys of the Zionist Movement. They stood for selfsufficiency and might, and their members tan and strong were the epitome of the new Jew, the “sabra.” Right after the establishment of the state, in 1948, Israel found itself fighting for its survival. Most male kibbutzniks joined the fight, forming the backbone of the armed forces. And they paid a very heavy price: Twelve percent of the casualties of the War of Independence were kibbutz members.

Muki Tzur: The war destroyed a lot of things internally, psychologically.

Yochai Maital (narration): That’s Muki.

Muki Tzur: Muki Tzur, I am a member of kibbutz Ein Gev for the last sixty years.

Yochai Maital (narration): And a leading historian of the kibbutz movement.

Muki Tzur: You know people who had dreams, you know, like to make a revolution, a pacifist revolution, to create a society by voluntary organization. To create a new world, and they find themself in war. And people find themself with death, destruction, personal fears. They were regular people went to the war, and when they came back from the war, the state had no time for them. Because huge immigration came into the state.

Yochai Maital (narration): In the early 1950s, just as Israel was trying to recover from the devastating violence, and get on its feet, a massive wave of immigration from North Africa and the Middle East flooded the country. The government was totally focused on the mammoth task of absorbing them.

Muki Tzur: Imagine today, people are scared of immigration to Europe. And they say ‘one million, how can we absorb one million? It will break Europe!’ And then you have a society, that had to absorb one and a half the quantity of the people who are living there. The state had no time to deal with the old voluntary society, you know?

Yochai Maital (narration): Now maybe, as Muki says, the state had more pressing matters to deal with, but its legendary leader, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion found the time to lash out against the kibbutzim. In a speech he delivered in the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, in 1950, the “old man,” as he was fondly called, didn’t hold back any punches “where is the kibbutz movement when it comes to helping out with immigration?” he asked. “They’ve done so splendidly for themselves, but what have they contributed to the task of absorbing the new aliya? I’m deeply ashamed of the kibbutz movement.” This statement triggered a heated debate within the kibbutzim. It was part of a much larger clash between various different political parties in the new country’s left and center. The irony was that all in all, they were pretty similar, much closer to each other, ideologically, than they were to say Jabotinsky and Begin’s Revisionists. But as often happens within groups with similar ideologies, the internal disagreements even on minor points can get out of hand, and cause tremendous ruptures. Just think of the history of the Christian Church, for example, or the backstabbing between Trotsky and Stalin. As you can imagine, there were countless divides within Israel’s early Socialist movement. It’s really complicated, but in broad terms there was a split between BenGurion’s supporters members of Mapai the historic Labor Party, and the more leftwing parties Achdut Ha’Avoda and Map”am who saw themselves as the true bearers of Socialist Zionism. In some ways, it was a local version of clashing Cold War ideologies. BenGurion was steering the country towards the West, while EinHarod’s own Itzhak Tabenkin, and the other leaders of the kibbutz movement, many of whom immigrated from Russia glanced Eastward with admiration. They looked up to Stalin, and saw BenGurion’s maneuvers and harsh rhetoric as a crude attempt to solidify his rule, and discredit any ideological adversaries. Ein Harod was in the eye of the storm.

Yisrael Smilanski: Most of the leader of the kibbutz meuchad were in EinHarod. EinHarod was the capital city of the kibbutz meuchad.

Yochai Maital (narration): That’s Yisrael Smilanski.

Yisrael Smilanski: I am a native. I was born in this kibbutz.

Yochai Maital (narration): Yisrael’s 84 years old, a retired farmer and former music teacher. He boasts that five of his sixteen grandchildren still live on the kibbutz. But sixty-five years ago, when all this ideological turmoil was taking place, Yisrael was just a young soldier. In 1952, after he was discharged from the military, he came back to a home he could barely recognize.

Yisrael Smilanski: The kibbutz was in two groups that couldn’t speak to each other. The situation in EinHarod was very bad. It was… two sides of the the dining hall, it was divided into two section.

Yochai Maital (narration): At first, like a feuding couple, members of the kibbutz tried to work things out and come to an agreement that would allow them to carry on. But the arguments just became louder and louder, and the two factions drifted apart: An actual line was drawn down the middle of the cheder ochel the very heart and symbol of communal life. And that simple white line had the power to split close friendships, and even families. Rachel Letzter was a child at the time.

רחל לצטר: ההורים היתה להם בעיה איך לאכול, כי הם לא ה יו יכולים לאכול ביחד. אז היא [אחותי] היתה מביאה להם .ה רבה פעמים אוכל הביתה. מאוד קשה. מאוד קשה

Voiceover (Rachel Letzter): My parents fought all the time, and they had a big problem they couldn’t sit and eat together. So I remember my sister would constantly have to bring them food back to our home. It was really difficult.

Yochai Maital (narration): Rachel’s was a mixed family, and she was torn between her father and mother.

רחל לצטר: חגים אני זוכרת שהיינו נוסעים לדודים, חג רציני כמו פסח שאי אפשר היה לחגוג ביחד, הייתה בעיה. היינו נוסעים למשפחה של אמא של בקריות

Voiceover (Rachel Letzter): On the major holidays, like passover, we would have to go to the city, to my mother’s family, because we couldn’t celebrate together on the kibbutz.

Yochai Maital (narration): Ein Harod’s school was the main ideological battleground. Officially, it was run by Mapai BenGurion’s party but most of the teachers belonged to other factions. These young idealistic educators were actively taking sides in the classroom, drawing students after them. Rachel’s two older sisters were teanagers at the time, and followed their teachers. The mother was on their side as well, but her father was a staunch BenGurion supporter. Eventually, the parents decided to split their kids between the two factions the pragmatists of BenGurion’s ‘ichud ’ and the ideologues of Tabenkin’s ‘meuchud.’ Ironically, both those words, ichud and meuchad come from the same Hebrew root yachad which means united. Rachel, who still lived in meuchad at the time, started going to school in ichud.

רחל לצטר: אני זוכרת שללכת לבית ספר המשותף היה סיוט! סיוט! בשביל להגיע לבית ספר של האיחוד הייתי צריכה להיפגש איתם [חברות שלי] על המדרכה. הרגשתי בוגדת. לא רציתי שיראו אותי. הסתתרתי. לא הייתי מסוגלת ללכת לבית ספר. הייתי מסתתרת או מחכה עד הרגע האחרון

Voiceover (Rachel Letzter): Going to the new ichud school was a nightmare. literally a nightmare. on the way to school i’d bump into my old friends, who still went to our old school, of the meuchad faction. and i felt like a traitor. i didn’t want them to see me, so i’d hide.

Yisrael Smilanski: One of the women that was in our group, she came up and said I had a son, his name was… As if he was dead. It was impossible to listen this kind of lamentation. It was horrible.

Yochai Maital (narration): The kibbutz descended into a tension filled silence. People on both sides were engaged in espionage and sabotage against each other.

דניאל לוז: אני בצבא הייתי קצין מודיעין, ואחי היה חשמלאי. גמר בטכניון

Yochai Maital (narration): “I was an intelligence officer in the army,” Daniel Luz recalls. Growing up, he and Yisrael the proud grandpa had been good friends. They even had Russian nicknames for each other Daniel was Ivan and Yisrael was Vassil. But the split severed all that Sovietstyle camaraderie. Yisrael was an ichudnik, backing BenGurion’s Mapai, and Daniel, on the other hand, joined meuchad. Together with his electrician brother, Daniel snuck into the children’s center, where the ichud folk would meet up to strategize.

דניאל לוז: אנחנו העברנו קו עם רמקול בתקרה. זאת היתה תקרה חלולה עם עלייה כזו. שמנו רמקול שם. ישבנו במקלחת ואנחנו האזנו בעצם למזכירות שלהם למפקדה שלהם, מה מתכננים מה לא. מתכננים

Voiceover (Daniel Levi): We hid a wiretap in the ceiling, and we would sit in the shower and listen to their headquarter meetings. that way we knew what they were planning, and what they were up to.

Yochai Maital (narration): Later, the Luz brothers ransacked the place. Here’s Yisrael again.

Yisrael Smilanski: The whole thing was very bad, it was very hate from both sides.

Yochai Maital (narration): Muki, the kibbutz historian, also remembers those days.

Muki Tzur: People said, ‘how is this happening to us? We love each other… we were with the… You know, they entered into a tragic trend. And a tragic trend is something… like destiny we can’t control it.

Yisrael Smilanski: And was fights, really fights.

Yochai Maital: Like fistsfights?

Yisrael Smilanski: Yeah, fights. Like in the movie. [laughs]. It was… and in the dining hall there was fight also.

Yochai Maital (narration): Fights broke out more and more frequently over the use of a tractor or the division of a field of crops. After a few youngsters took over a house that belonged to members of the other side, a giant brawl began. Basically the entire kibbutz participated. Eventually cooler heads prevailed. But the rift was so deep, that people on both sides realized that this liminal state was untenable and that a split was unavoidable. So the two sides appointed mediators, members of other kibbutzim who helped them negotiate the terms of the breakup. Ultimately, about half of EinHarod’s members left to form a new kibbutz, EinHarod Ichud, directly adjacent to the old one. But the divorce just got uglier and uglier.

דניאל לוז: כל צד, את מה שהוא היה יכול להוציא החוצה .ו להבטיח שהוא ישאר אצלו? הוציאו

Voiceover (Daniel Levi): Each side took whatever they could with them.

Yochai Maital (narration): That’s Daniel Again.

דניאל לוז: פרות? פרות אנחנו הוצאנו לבית אלפא. מכונות ב מוסך, כלים במוסך. אין לך מושג למה זה הגיע. עמודי חשמל ש עוד לא נבנו והוציאו. ציוד שהיה אפשר להוציא הוציאו. רבו על .מ שאיות. היו שתי משאיות, אחת טובה ואחת פחות טובה

Voiceover (Daniel Levi): Cows, heavy machinery from the car repair shop, you have no idea how far it deteriorated… people took electricity poles. everything. we fought over trucks. there were two trucks, one was good, and the other one was pretty crappy.

Yochai Maital (narration): In the “divorce settlement,” Daniel’s side, EinHarod Meuchad, got the crappy truck. But he and his friends weren’t going to let that fly. So in a wellplanned militarylike commando operation, they snatched the other truck. A month later, as the truck was out delivering goods in the area, the meuchad driver was ambushed.

.דניאל לוז: זרקו אותו מהאוטו, ולקחו את המכונית חזרה

Voiceover (Daniel Levi): They threw him out, and took the truck back.

Yochai Maital (narration): It went back and forth like that for a while. Retaliations upon retaliations upon retaliations. Ultimately, things started to settle down, and all that was left was the pain.

Muki Tzur: And then you have the period of mourning silence, people don’t speak about it. It was a very very difficult moment.

Yochai Maital (narration): Each kibbutz concentrated on rebuilding itself, but EinHarod, just like the entire kibbutz movement really, never returned to its previous glory. With time, the open wound morphed into a nagging scab, which the old timers, at least, will carry with them to the grave.

רחל לצטר: אמא, אחרי שהיא עברה לאיחוד, היא לא הלכה לבקר את החברות שלה אף פעם.

יוחאי מיטל: ואו.

רחל לצטר: לא הלכה. ואבא שלי לא התקרב למאוחד. עד יומו האחרון

Voiceover: My mom never went back to visit her friends after she moved to ichud. not even once. and my dad? didn’t set foot in meuchad till the day he died.

רחל לצטר: אני חקרתי אותם כמה פעמים. כשהייתי כבר אדם נשוי עם ילדים, להבין איך עשיתם את זה? למה עשיתם את זה לנו? מילא אתם, אבל למה לנו? זר לא יבין זאת. תאמין לי אי אפשר להבין את זה. פה היתה מלחמת אזרחים

Voiceover (Rachel Letzter): Once i grew up, and had children of my own, i asked them about it. i wanted to understand how they could do such a thing. how they could have put us kids through all of this. believe me, i don’t think anyone who wasn’t part of it can ever really understand what went on here. it was a civil war.

דניאל לוז: תראה אני גם כן לא… אני הולך לאיחוד. לאישה יש חברים… אני הולך אבל לא… אם יש שמה מופעים בחדר אוכל. אני לא הולך

Voiceover (Daniel Levi): Look… what can i tell you… i go to ichud from time to time. the wife has friends there, so I go.. but if they have some sort of performance in the dining hall, i don’t go.

Yochai Maital (narration): Before the split, when Daniel and Yisrael still called each other Ivan and Vassil, their fathers were also good friends. They too broke along party lines. Decades later, they met up in the regional old age home.

Yisrael Smilanski: And they spoke together what happened? Why we split, why this happened? And they sat there and tears fell from their eyes.

Muki Tzur: After a while they asked themselves, ‘why we did it? What happened to us?’ And silence came. Nobody was ready to speak about it.

.רחל לצטר: אידיאולוגיה היא הורסת עמים. תחשוב על זה

Voiceover (Rachel Letzter): Ideology… is the ruin of nations. think about it.

In Act II, “Prison Prayer,” Shoshi Shmuluvitz revisits her first big high-school love, Jonathan. He lived in London, she was in New York. He was into drugs and music, she was a studious introvert. But they fell hard for each other, loved intensely, and then crashed and burned. Recently, she got back in touch with him, to talk about what they had, and what they lost.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): I’m sitting on my couch with Jonathan, a skinny ultra-Orthodox Jewish convert with a long wispy beard, sharp cheekbones, and big, expressive eyes. The table is covered with half empty cups of tepid coffee and Jonathan’s cheap Israeli cigarettes, which he pulls the filters out of before smoking. We’ve been here talking and looking at old photos of us for the past three hours.

Jonathan: You’re looking at a photo of Shoshi kissing my eyebrow. What do you think of when you look at that photo, Shoshi?

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: I don’t know.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): What does our relationship — our first love, which, in some ways, never really ended — what does it mean? That’s what I’ve been trying to figure out for the past year and a half, ever since Jonathan began calling me from the Israeli prison where he was doing time.

Jonathan: When they were like, “whose number do you want?” I was like, “Give me Shoshi’s number.” That’s the first number I asked for.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): We hadn’t spoken in years, so, at first, I couldn’t understand why he was calling me — or why I kept answering. But a long time ago we were in love, and now he was on suicide watch. I met Jonathan twelve years ago, when we were both 18. His dad, who lived in London, and my mom had been friends in the 70s. They’d lost touch for years, and my family lived in New York. So we didn’t all meet until my senior year of high school, when we spent a weekend in London at Jonathan’s family home.

Jonathan: You roll up in the black Audi cab. Like, I didn’t really think that much of anybody getting out of a car until you got out of the car. In the moment when you meet someone and there is that cosmic feeling it’s hard to meet anyone who has ever felt that feeling and not just run with it, see where this goes. See where the rabbit hole ends up and that’s sort of where I went.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): From that moment, until I left London, Jonathan and I were inseparable, which was surprising: I was painfully shy, sheltered, and very studious; Jonathan was a charismatic prep school dropout with dreadlocks and a smoking habit. We all spent that weekend touring the London Eye and the British Museum, sampling the chip shops. We’d pile into Jonathan’s dad’s minivan, Jonathan and I sitting way in the back, oblivious to anyone else. Neil Young’s Harvest Moon was stuck in the CD player and it became our soundtrack. On the second day, Saturday, Jonathan kissed me.

Jonathan: We were making out and I went to slip a couple of pills, and you went “what is that, what are you taking?” and you were freaking out and I was like “no, I’m taking a sleeping tablet,” and I lied straight to your face. “Yeah I’m taking a sleeping tablet,” “oh okay,” and I was like alright, fine.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Months later he’d confess that he was a drug addict, that he’d quit school after a cocaine overdose.

Jonathan: When we met I was a mess. I’ve been a mess most of my life, and when we met I was a mess too. I had been messing around with a lot of cheap cocaine renditions, cheap speed renditions, and a lot of psychedelics. I probably had my first joint of cannabis at about 11.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): That was around the time of his parents’ divorce.

Jonathan: I had a nature for addiction it seemed. I feel that a lot of things in my life not just drugs I have a tendency to become addicted to them in a very deep way, whether it’s my magic tricks or music or my spiritual life. Also with women as well.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): But that weekend at least, that one little valium was the only thing he took.

Jonathan: We just hung out. We were together the entire time, I didn’t feel the need so much. I hadn’t touched anything. On the way back from the airport it dawned on me that I was coming down — coming down off of a bunch of different stuff that I’d been taking up until you’d arrived. That was the last time I had touched anything like that for the remainder of the time we were together until we broke up.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): When we first met, Jonathan had still been using, but he had been cutting down. The worst of his drug use seemed to be behind him. And he had hope for the future: he’d just gotten his high school equivalency and been accepted to nursing school.

Jonathan: I was living with my dad and my sister, things were idyllic in that sense. I had a roof over my head and I felt that my writing, my musical writing was very good and I started messing around with poetry and writing and things like that.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): When I got back home to New York, Jonathan and I began talking on the phone — a lot. And it was through those hours and hours of long distance phone calls that we just fell completely in love.

Jonathan: It makes sense that our entire relationship has been one of words because the first thing you ever bought for me was a book by Pablo Neruda, and in it you say, ‘Love begins when a woman enters her first word into her poetic memory,”

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): I stole that from Milan Kundera. But love is really about building a new dictionary, a specific dictionary that is just between the two of you where one word that’s seemingly innocuous is a very important thing all of a sudden. For us, it was very much the speaking and listening to each other. I think, first time we had a friend who was prepared to listen to all of the BS in our brains and in our hearts.

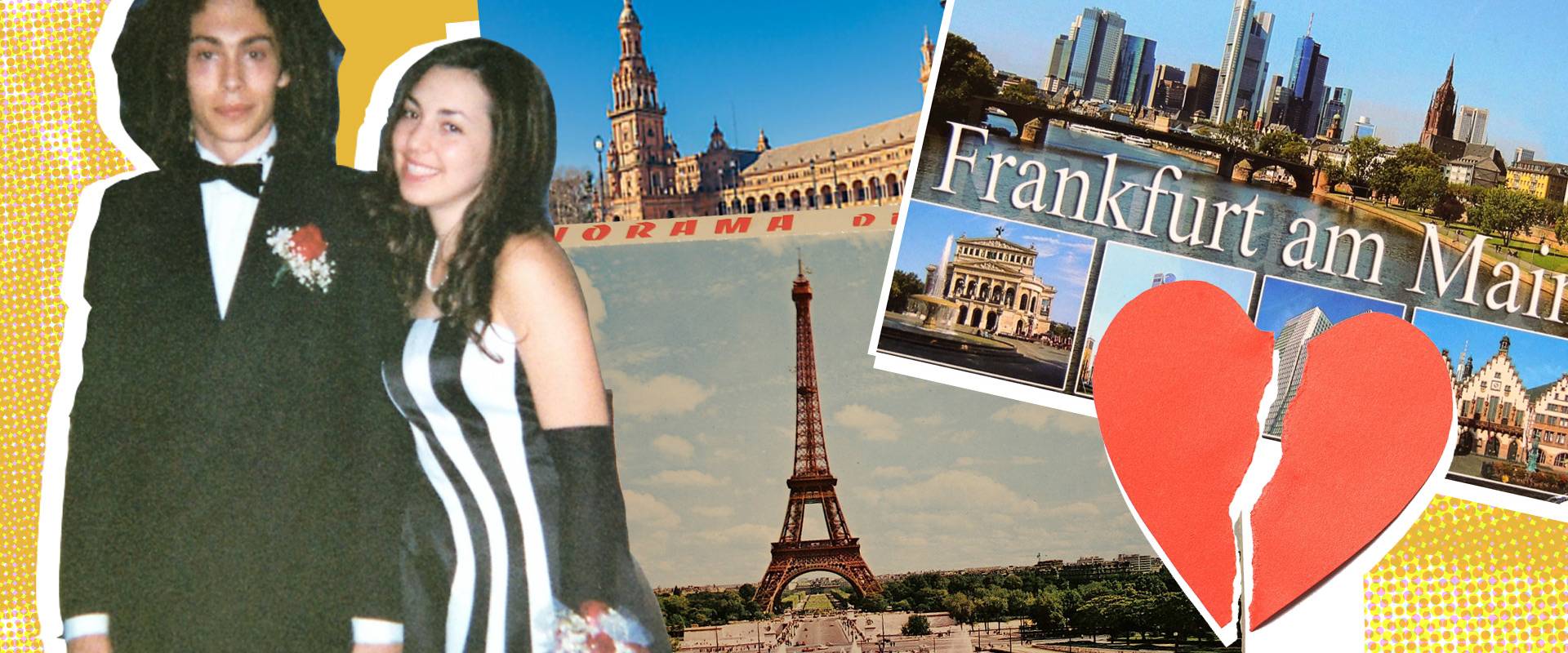

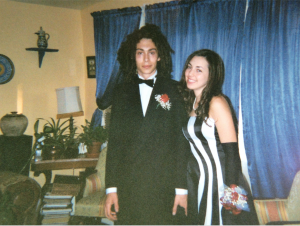

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): After two months of that, Jonathan landed in New York. It was early June, my last month of high school. I cut class and took Jonathan to ride the cyclone in Coney Island. He bought me a corsage and took me to prom. And it was dreadful, but I looked great. I turned up in my tuxedo and my dreadlocks just looking completely ridiculous and you looked like something out of a 1950s romance movie.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): When we walked into that ballroom, jaws literally dropped. Pretty much anyone who saw us together was taken aback: we seemed like such opposites. But once they got to know him a little, everyone loved Jonathan. He was charming and kind and my parents treated him like one of the family. He left on the day of my graduation, which I skipped so I could see him off at the airport. Two long weeks later, I was on a plane. We spent most of that summer at Jonathan’s dad’s house in London. One morning we went to Hampstead Heath, ate an entire lemon meringue pie for breakfast and then skipped across the lawn shouting, “And they were blissfully, blissfully happy, forever and ever and ever.” It was line from a series of very silly internet videos called Tales of the Blode. But we believed it. We were eighteen and we were so sure that we’d always be together and that, as long as we WERE together, we would be as happy as we were in that moment. Full of love, full of pie, in a beautiful park, on a beautiful July day in London. We were sure of it despite his parents’ divorce and my parents’ lackluster marriage. We were sure of it because before we met, he was a drug addict and I was so lonely. And now, he was clean. I was connecting with people. Together, we’d undergone an almost magical transformation. And to us, our relationship seemed otherworldly, preordained, sacrosanct. And then, we visited his mother in a quaint seaside village called Somerset.

Jonathan: You were the first woman I had ever introduced my mother. And I think that was a shock for you, meeting my mother and to have that Somerset experience. When we were there there were access to a lot of drugs, right in front of us all the time. I remember we were sitting at a table, drinking coffee smoking cigarettes, smoking a bit of pot and someone dropped 5 grams of, whatever on the table and just said “you don’t want any of this do you? For free, right here, right now? You and the lady?”

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: So your hands started shaking and I pulled you out of there.

Jonathan: Oh so it was you who saved me. Okay … eh it wouldn’t be the first time you had done such a thing.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): That scene in Somerset left me deeply disturbed. It was the moment that I first understood the extent of Jonathan’s addiction — and his tendency for selfdestruction. I loved him in spite of it, and I was certain that that love would save him. At the end of that summer, I went back to New York and started college. Jonathan started nursing school in London. It was a difficult adjustment, and a lot of pressure for each of us. By midterms, our relationship had fallen apart. But a few months later, around the time Jonathan quit nursing school, we started talking again. And that summer, he came to New York to try and make our relationship work.

Jonathan: That was also quite an amazing summer, the first time I’d seen fireflies.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): We slipped right back into love, even though we knew the long distance thing was not sustainable. To stay in the country, Jonathan would either have to get into school and get a student visa, or I’d have to marry him so he could get a green card. He wanted to get married and start a family — and soon.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: Why do you think that’s always been so important to you?

Jonathan: Well Freud, I think that the obvious reason is the lack of stability in my own family causes me to reach out and try to create a stable family. I suppose that’s what Freud would say.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: We were at a stalemate.

Jonathan: You chickened out on the marriage, that’s really what happened. Like, straight to the point.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: I was 19 years old, I didn’t wanna do it.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): And Jonathan never applied to universities in the US. He didn’t WANT to go back to school. That was it, you know. Although we stayed together till the end of the trip obviously, didn’t change anything but it did cement the fact that it would end, that it would have to end. It didn’t end; we kept talking on the phone every day. I was in love with him but I still wasn’t going to marry him: we were too young, I cared more about school and building a career, and Jonathan was still completely directionless in that respect. He felt me slipping away, so he drove me away. He knew exactly how to infuriate me, by constantly picking arguments, by twisting my words and playing devil’s advocate to everything I said, even if I was just stating simple facts. It became impossible to have a conversation with him. And after a few months of that… I lost patience and gave up. Somewhere, though, I held onto a sliver of hope that we’d eventually find our way back to each other.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: What happened to you after we broke up? What was going on in your life?

Jonathan: I came back to England and I crashed. I crashed and burned. I began to use the psychedelics heavily and one thing led to another and I ended up on a bit of powder. But not enough to get cracked out on. And then I went to an Aish lecture with a Rabbi and that’s how that whole road began just after that.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): That’s when Jonathan became an ultra-Orthodox Jew. It was surprising, but then again, it wasn’t. He’d always been interested in the spiritual. As a teenager, he’d studied the occult and could read tarot cards and runes. Later, he read the Qur’an, the old and new testaments, the Bhagavad Gita. He seemed always to be searching. Years passed. I graduated college. He got clean again. And then he moved to Jerusalem to study at a yeshiva. At the same time, I moved to Tel Aviv to study Middle Eastern History. So we decided to meet. It was August 2009, exactly four years since we’d last seen each other. I had no idea what to expect. Now that he was ultra-orthodox, I didn’t know what he’d look like, or how I should greet him, whether he was shomer negiah and avoided contact with women. He met me on Ben Yehuda street wearing black pants, a white button down, and a beret instead of the traditional black fedora. He’d grown a scraggly beard and sidelocks, which he tucked behind his ears.

Jonathan: And we gave each other a big hug. And we sat on the beach under the full moon listening to random pieces of music on each other’s iPod. and that was a very very intense moment.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: That old chemistry was back.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): It felt like nothing had changed between us, and despite his new look, he was still Jonathan. We sat up all night on that beach, talking, until just before sunrise. And in that moment, anything could have happened.

Jonathan: And nothing happened, not so much as a kiss happened.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Because even though it was the first time we were living in the same country, we were further apart than ever. We didn’t just have different values and goals in life; now, he was religious and I was secular and neither of us would change. But that night, even though I realized that we would never get back together again, all the old feelings had flooded back. I expected closure from that meeting, but I came away racked with confusion. It should have been a postmortem of our relationship, but instead it had turned into an epic date. A date with someone I had serious feelings for, but who was completely unsuitable for me. After that night on the beach, Jonathan and I stopped talking again, for years.

Jonathan: I went through a very dark time after that. (laugh) Sounds like I’m always in a dark time, there were many years in between that relapse and the other one. I was just drinking a lot, very depressed. And then I met my wife online on a poetry website that she had created. I was on there and she liked one of my poems and we got chatting.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Tamar was 19 years old. She came from a family of messianic Christians who had all converted to ultra-Orthodox Judaism and moved to Israel.

Jonathan: We had a lot in common in that we both didn’t have much of an academic education but both very much enjoyed learning things. and we had a very very deep attraction to each other from day one. But it was beset with issues from the get go. A member of her family was very much against the idea of me. He thought that everything was too fast, he didn’t like the fact I had a history of drugs.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Jonathan called to invite me to his wedding. By then, I’d stopped harboring any romantic intentions towards him. But it still felt surreal and a little soul crushing. I wanted to be happy for him, but instead of a sense of closure, I had an ominous feeling about the marriage: it WAS happening quickly, and Jonathan still didn’t have a career, or much direction at all. I got the sense that he was as unstable as ever. And I hoped that I was wrong. I hoped that things WOULD work out for him. I made up an excuse why I couldn’t go to the wedding, and congratulated him. We didn’t talk again until he called me from prison. After Jonathan got married, he began formal studies to become a rabbi. He started writing more seriously. And he and Tamar would host these huge shabbat dinners. He was really building a life for himself.

Jonathan: We got pregnant straight away and I have to say that pregnancy is possibly the most incredible thing in the universe. Your child growing between you, it was magical. Shlomo was a shabbat birth. And I walked into the room, me and a wife, and I came out as a family, holding this little screaming pink thing. And they say something happens to you when you hear the cry, for me it was true and I heard that cry and I don’t know, something changed.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Jonathan finally had his own family — it was exactly what he’d always wanted.

Jonthan: And then I … destroyed my marriage basically.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Throughout the marriage, he’d been casually using drugs.

Jonathan: LSD and weed and things like that. Very often without anyone knowing.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): It became more serious when he began suffering from back pain.

Jonathan: I started taking the oxycontin and just about anything else that had opiates in it and smoking a lot of those and mixing that with high levels of LSD and things like that, with valium and with ritalin and with psychiatric medicines and anything I could get my hands on. I don’t know what happened. I was good for so long as well, and I had a blip. And I went way off the deep end. And it got there in a couple of weeks. A lot of my savings I burned on the Oxycontin in about three, four months. Things got more and more and more unstable with me. everything was on its head, lots of missing time.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): And then, one night, it got much worse.

Jonathan: I’m not exactly sure what happened is the truth because I know I way way over did it that night. And I blacked out and when I woke up, my wife was crying in the corner holding her… our baby when I started coming around. she said I had threatened her, threatened to kill her, had a knife to her throat, dragged her back into the house by her hair and threatened to kill the kid. I find it hard to believe that that’s somewhere inside me. whether it was a verbal threat or a physical threat or whatever, that wasn’t part of our relationship before or after it was like this one terrible moment that… for me to understand that it was that serious is very difficult.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Tamar took the baby and went to stay with her parents. Within a few days, Jonathan patched things up with her and she came back home. He tried to cut down on his drug use. Things seemed to be getting at least a little bit better — until, six months after that awful night, Tamar and Jonathan had an argument.

Jonathan: I stormed out, I got a call from the police that they were at the house with my wife. I naturally assumed something happened, she hurt herself. I didn’t realize I would get arrested. I don’t think she really realized I would get arrested either.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Tamar had told the police about the incident that happened six months before. They arrested Jonathan for domestic abuse, and they told him he could get a maximum sentence of ten years. And he believed them.

Jonathan: For ten years, I wasn’t going to see the sunlight. I wasn’t going to live by myself or take a walk in the street or hold my boy for ten years. And so I ruined my best chance of having a normal time in prison by trying to kill myself.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): And that’s when he started calling me a few times a week — when he was on suicide watch. I’d never known Jonathan to be violent so when he told me what he was accused of, I was shocked. It was July 2014, the height of Operation Protective Edge, the latest round of fighting in the Israel-Gaza conflict. I was working as a journalist, and as soon as the war broke out, I went from covering concerts and conferences to protests and funerals. I’d go out and interview people whose relatives had been killed, people who were filled with grief and despair and rage. And then I’d go home and get these phone calls from prison and it felt like another emotional burden. I was powerless to help him but felt morally obligated to keep answering his calls. He’d hit rock bottom, and he hardly had anyone to talk to; after what happened, a lot of his friends in Israel just abandoned him. When I answered the phone, he would start rambling so that it was difficult to understand him. He’d recount memories from the time we were together, stories we’d both forgotten that resurfaced in his mind as he sat in solitary confinement. We would talk about meeting up for coffee when he finally got out, which I knew I would avoid. And he’d read me poems that he’d written about his son and about me.

Jonthan: In the meal of love, dessert was served first. The eyes you once cherished burn now with sorrow. And I’m ready now to throw myself to the one who might catch me again

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): More than a decade earlier, when we were 18, it was me reading a poem I’d written for him over the phone. Now, those prison phone calls were an unsettling parallel. I still loved Jonathan, but it had become a very different kind of love. It had gone from being purely romantic, to familial. It was gut wrenching to bear witness to his ruin and when we hung up, I felt drained. But not Jonathan.

Jonathan: I was thinking about life in New York a lot as like a really big turning post between my realities. I thought about my time clean with you, you know, totally clean. And it was very helpful to have your voice in an extreme situation. And I knew that you wouldn’t slam down the phone on me if I told you I was in jail.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: How did you know?

Jonathan: I know you.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): All together, Jonathan served a seven month sentence for verbal domestic threatening and one count of battery for shoving his wife against a wall.

Jonathan: The first day out of jail was so powerful. I was down in Yafo, in Tel Aviv, looking at the sea. I broke down in tears — the beauty of it.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): A year later he was on my sofa and we were looking at that old photo.

Jonathan: These guys in the photo could have made it.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: It was impossible, like we had a romance and then it was unsustainable and that was it.

Jonathan: So then why have you done a whole interview about it? You don’t feel that at all. (laughs) That’s complete and utter junk. Who are you kidding? It’s one of the defining romances of your life.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz: Yes.

Jonathan: Okay. I’m okay with saying that. It’s a tragedy they didn’t make it. And although I have loved — and rather intensely — after you, none of them have been the defining romance of my life, even my marriage. That’s why you’re the first person I called from jail. That’s why you’re doing an interview. That’s why we don’t meet up.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): It WAS the defining romance of my life. And the truth is, I haven’t loved anyone the way I loved Jonathan. Since we broke up, I have had romance and love in my life. But it was never as intense. I don’t know if that’s because of who Jonathan is, or because of the mysterious connection we’ve always had, or simply because he was my first love. But I do know, and I think I’ve always known, that I’ll never have a love like that again. And that’s why, for over a decade, I carried around a horrible sense of loss, like a hollowness that echoed through all the years and relationships since. That’s why I answered Jonathan’s prison phone calls. That’s why I did this interview. And now, after pouring over the artifacts of our relationship, that sense of loss has dissipated. By saying out loud how big our love was for me, it’s now somehow easier to just hold it — not clinging, but also not pushing it away. Jonathan helped me do that. Now, we’re friends. I don’t dread his calls anymore. And he’s right — wherever he is, whatever’s going on with him, I’ll always pick up the phone.

Act III, “Anywhere,” is about the lengths we will go to win a person back. After Mishy Harman’s girlfriend, “the one” as far as he was concerned, dumped him, he hitchhiked around the world to prove to her that he was “flexible.”

Act TranscriptMishy Harman: At the end of the summer of 2008, my girlfriend Natalie, who I was absolutely sure I was going to marry, broke up with me. It was kind of surprising, and totally onesided, and mainly just devastating. And what’s more, after nearly two intense years together, it was… over the phone. One of the things that she said in that last fateful phone call was that I wasn’t flexible enough. Honestly, I had noticed that myself, how I was rigidly wedded to certain ways of life, and how it would be almost impossible for me to change my mind, even on small things like what we’d order at a restaurant. So I took her criticism to heart. I was just about to move to Cambridge, England, to start a master’s in archeology, and the quest for flexibility became the theme of my life. I wasn’t absolutely sure what she had meant by it, but I decided on an allout approach: If I was going to become flexible, I thought, it would be in every possible way. So I joined a yoga studio, signed up for some pilates classes, did my daily morning stretches. For months, there was one thing, and one thing only, on my mind: How to show Natalie that I’d become flexible, and win her back. Now, I knew of course that her complaint didn’t really have to do with the fact that I couldn’t touch my toes, so I was constantly searching for ideas that would expand my flexibility. And one rainy night, as I was walking back to my room from a screening of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, I had this idea, which seemed both simple and exciting. If I really wanted to become flexible, I needed to place myself in a situation where I had no control over the outcome. By the time I had reached my room, I’d thought of the perfect solution. It was the middle of the semester, but instead of opening my lecture notes on Mesopotamian archeology, I found a cardboard box, tore off a small rectangle, and scribbled “anywhere” on it in big blue, all caps letters. I threw some clothes, a tent and a sleeping bag into a backpack, and went outside. My idea? To hitchhike to… well anywhere.

The rules were simple: I would accept any ride, and that way I would literally have no control over where I was headed. Or at least that’s what I told myself. You see, even though this was designed as this sort of no set destination kind of romantic odyssey, it’s hard maybe impossible to shed years of inflexibility in just one evening. So as I stood on the side of the road, my thumb stretched out like I had seen in 1970s European movies, I harbored this secret desire that if things went really really well, I would end up in Seville, in Spain.

The Seville dream wasn’t entirely random. Growing up, my older brother Oren had told me about his favorite paradox. It was about a barber from Seville, who shaves all the men in town who don’t shave themselves. The question, Oren explained, is whether or not the barber should shave himself. It’s a classic paradox, because if he does shave himself, he shouldn’t, but if he doesn’t then he should. Now I know this isn’t totally rational, so bear with me, but in my slightly obsessive and hazy state of mind, I felt some close affinity to that poor fictional barber. We were both going through endless mind loops him about shaving people, and me about trying to be flexible enough to get Natalie back, even though that dogged desire was itself a prime example of my inflexibility. Anyway, I decided that I had to search for this barber. Maybe, once I found him, we could put our minds together and break out of our respective maddening, rabbit holes.

Not many people stopped to offer me rides, and I began to feel that I had missed the window of opportunity for my ideal fantasy by about three decades. I walked to the freeway outside of town, and held up my sign. Barely anyone noticed me. The few who did slowed down, read the sign, kind of smiled, and whizzed off.

Half the night passed before someone stopped. He was an elderly Pakistani man, who was on his route to refill soda vending machines. He took me to Newmarket, the next town over, where I was picked up by some stoned members of a teenage punk band, who stopped to rehearse at some grindy basement nearby. The farther I got from the large cities getting rides got easier, and it was all kind of exhilarating. I was having a blast, mainly because I felt I was becoming more flexible by the minute. Natalie was going to be so impressed.

Almost immediately it dawned on me that Natalie would only be impressed if she knew about my journey. But since we weren’t really talking, and she was halfway around the world, I decided I would write her postcards, which would chronicle the adventure and my growing flexibility. There would be one postcard a day, telling her everything I saw and learned. But quickly, too much was happening for just one daily dispatch, and I found myself writing two, three, sometimes even four, five or six postcards a day. Now, I was definitely not exactly stable, but I also wasn’t crazy. And even in the middle of it all, I realized that she wouldn’t really appreciate receiving dozens and dozens of unsolicited postcards from me. So I started keeping them, stamped and ready to go, in a large manila envelope in my backpack. In my imagination which was in overdrive mode throughout the trip I would present her with the whole bundle one day. And she would read them, and see just how much I missed her, and melt.

I was also going to give her another gift: On the flip side of my anywhere sign, I wrote in the same big block letters “I Love You, Natalie.” And I did that because I figured that I was meeting so many strangers, from so many different places, that I would take snapshots of them holding up the sign, and then make an album with a whole world worth of people expressing my undying love. So… yeah. Dire times…

About a week into this trip, somewhere in Kent, I got into a van of gypsies, who were heading to Holland. They smuggled me onto the ferry from Dover in England to Calais in France, which seemed like a big step towards reaching my barber in Seville. Once I was on the ferry, I snuck into the truck drivers’ cafeteria, to see if any of them were going to Spain. Plenty of them were in fact heading there, but no seemed to want company. No one, that is, except for one tall, shy man, with dark hair, sitting in the corner, eating by himself.

That was Vladimir, who I later found out spoke not a single word of English. I asked where he was going, and he said ‘Spain.’ I was delighted. “Spain?!” I cried out, “that’s great! Can I come with you?” Vladimir didn’t really understand what I was saying, so he said yes, and that’s how about an hour later I found myself climbing into the cabin of his huge semitrailer and driving into the French night.

After Vladimir said “George Bush, George Bush,” we more or less exhausted all our common vocab, and continued in complete silence. Half an hour later, I suddenly noticed that Vladimir took an unexpected left hand turn, into Belgium. I looked at him, and sort of anxiously pointed south, yelled out “Vladimir Spain! Spain!” But Vladimir, who never seemed to get too excited about anything, just looked at me, a bit confused, and with some sort of a deadpan seriousness just said “No, no Spain, Ukraine.”

Thinking back I probably should have been concerned, but at the time there was only one thought going through my head: If there was ever a moment to practice my flexibility, this was it. Natalie was going to go bananas. So, for the next four days, Vladimir and I crisscrossed Europe, making our way to the Ukraine. He kind of taught me how to drive his truck, and managed to explain that we were taking the sideroads because he didn’t want to pay the tolls, and then finally we arrived at the Slovakian-Ukrainian border crossing near Uzhgorod. We were detained there, ‘cuz it turned out that Vladimir’s entire truck it was packed with counterfeit Barbie dolls that he was trying to smuggle into the Ukraine. Once the guards realized that I wasn’t part of the Barbie doll scheme, they let me go. And in some sort of Forrest Gumplike fashion, I figured that if I’d gotten this far from home, I might as well continue. So I traveled all over the Ukraine, stayed with Chabadinkim in Odessa, with Braslav Chasidim in Uman, and even saw the former centers of Eastern European Jewry in places like Lvov and Kamianetz-Podilskyi. It was the end of the winter, and I remember everything looking pretty drab and depressing. At night I would stay in cheap inns, or hostels, or with families renting out a room, or even a sofa, for the night. I ate a ton of potatoes, in every possible shape and form. But, and all in all, was quite lonely. But there were also fun moments, like when I went to the opera house in Odessa, and was I kid you not the only person left in the audience at the end of Verdi’s fourhour long ‘Don Carlos.’ Or when I stumbled into a magical hidden kingdom of pierogies in Kiev, and sampled every single kind. I ended up in Moscow, where I got off at the central train station, and boarded the Trans-Siberian Railway, which crossed all of frozen Siberia, Mongolia’s Gobi Desert and stopped, seven days later, in Beijing. There were almost no tourists on the train other than me. It was mainly Russian farmers going from one small village to another, and every night they’d throw the wildest vodka parties in the sleeping cabin. The train would make a whole bunch of stops each day, and I would run out to the platform, and snatch some pictures of locals holding up my “I Love You Natalie” sign. The pile of postcards also continued to grow. But, more than anything, I really did start to listen, and become a bit more flexible. I was collecting ideas and tidbits of wisdom along the way. In Kiev, at a particularly seedy youth hostel, I had stayed up all night listening to the stream of consciousness of a middleaged Canadian hockey fan. “You miss 100% of the shots you never take,” he quoted Wayne Gretzsky as we were saying goodbye. And then, a few weeks later, at the train station in Ulaanbaatar, I met a beautiful Swedish drifter, who told me that her life motto came from John Lennon.

It was almost Passover when we finally pulled into Beijing, and I went to a Chabad Seder at some huge function room in one of the fancy hotels. I sat down next to a gorgeous Israeli girl, Maya I think her name was, and began telling her about my hitchhiking adventure. She seemed very enthusiastic, and by the end of the evening asked me if I wanted to continue the odyssey, together, and hitchhike with her to India. I didn’t know what to say. Even though I had become completely swept away by the trip, I had never forgotten why I had set out on it in the first place. But could it be, I thought to myself, that this whole journey would ultimately lead me not back to Natalie, as I had hoped, but rather to opening up a new chapter with someone else? There was something both bitter and poetically ironic about that thought. I took down Maya’s email address, and told her I would write the following morning. Now, remember this entire trip took place in the middle of my semester. I hadn’t told any of my professors, and whenever they’d email to ask where I was, or how my thesis was going, I would reply that we must have just missed each other in the department, or something like that. But with Maya’s offer I began to wonder who really needed a masters from Cambridge anyway. I drafted a long email to my advisors saying that I wasn’t coming back. Luckily, I didn’t send it right away. The very next day I met up with Maya, to go over some logistics. And then, completely nonchalantly, she said, “yeah, and we can stop in Tibet on the way, and pick up my boyfriend Udi.” And I was like, “your boyfriend Udi?!” Udi, and the fact that I was getting a bit tired of this vagabond lifestyle, all seemed like a sign to me. Go back to the real world, it was saying, and to your boring thesis about Proto-Israelites and pig bones. For once, I listened. So I hitchhiked to the Beijing airport and asked the Chinese travel agent for a ticket on the cheapest same day flight going anywhere west of there. He started typing into his computer and then looked up with a grin. He informed me, in broken English, that I was very lucky because there were still tickets available on a cheap flight, leaving a few hours later, to Europe. “Oh, that’s wonderful,” I said, “Where’s it to?” And he looked down at the screen and back up at me and said… “Spain.” So… despite the very long detour, I did end up in Seville and I did go looking for a local barber. When I found one, he couldn’t have been farther removed from my fantasy. I had pictured this fat, balding Spaniard called Juan Carlo or Pedro. I thought he’d have a huge mustache, and would spout out words of wisdom about life within a paradox. But in reality, the barber’s name was Mustafa and he was a twentyyearold recent immigrant from Algeria, who had no idea what I was talking about. The Andalusian music I had imagined as the backdrop to this meeting turned out in the real world to be Celine Dion’s theme song from Titanic.

Other than an outrageously expensive shave, Mustafa didn’t give me any words of wisdom to take back home with me. A few months later, taking up Wayne Gretzky and completely ignoring John Lennon, I moved back to the States to be closer to Natalie and try to show her my new flexible self. And on her birthday that year, I invited her over to my place to present her with my labor of love. An album with pictures of more than a hundred people all over the world holding up my sign. A whole world of people all the way from Senegal to Afghanistan, telling her how much I loved her. On the shelf in my room, carefully tied with blue string, was the pile of postcards I had written to her. I thought I would bring them out at the most climactic moment of our reconciliation. But things didn’t quite turn out that way: She opened the picture album to some random page with a chubby toddler in Australia holding up a homemade “I Love You Natalie” sign. She sort of smiled, flipped one more page, and then gently closed the book. There was a moment of silence. I looked at her, and she looked down at the floor. And then, at least this is the way I remember it, she got up, put on her coat, and walked to the door. I was stunned, and cried out, “but wait, your album, you forgot it.” And Natalie looked right at me, and said, dryly, “oh, was I supposed to take that?”

I’ve seen Natalie a few times since, but that was our last intimate, if you can call it that, interaction. The whole story happened a long time ago, and has sort of entered this mythical place in my life. I’ve told it more times than you can imagine. For years I thought of it as my all-star story, and would tell it stupidly, I guess on every first date I went on. (You can just imagine how well that went…). And when you tell a story so many times, you sort of lose the experience of it actually happening to you. But when I try to strip it of all those additional layers, and go back to what it actually meant to me at the time, I’m left with this gnawing fear that maybe, probably, this crazy worldwide quest for flexibility was actually the best example of the complete opposite that compulsive rigidity and uncompromising stubbornness Natalie was running away all along.

A very special thank you to Mishy’s parents, David and Dorothy Harman, who did the voiceover recordings in the kibbutz piece. Thanks to HaZira – Performane Art Arena who gave us permission to use music from their great puppet drama – “The Road To Ein Harod” – and to the musicians Guy Sherf and Rona Keinan. Thanks also to our friends at TTBOOK, Charles Monroe-Kane, Caryl Owen, Steve Paulson and Anne Strainchamps.

Closing song: Layla Dmama (“Night of Silence”). Original melody by Moshe Bik. Lyrics by Naomi Bruntman. Covered by Guy Sherf and vocals by Rona Kenan.

For more sounds of Israel, listen to our featured song.