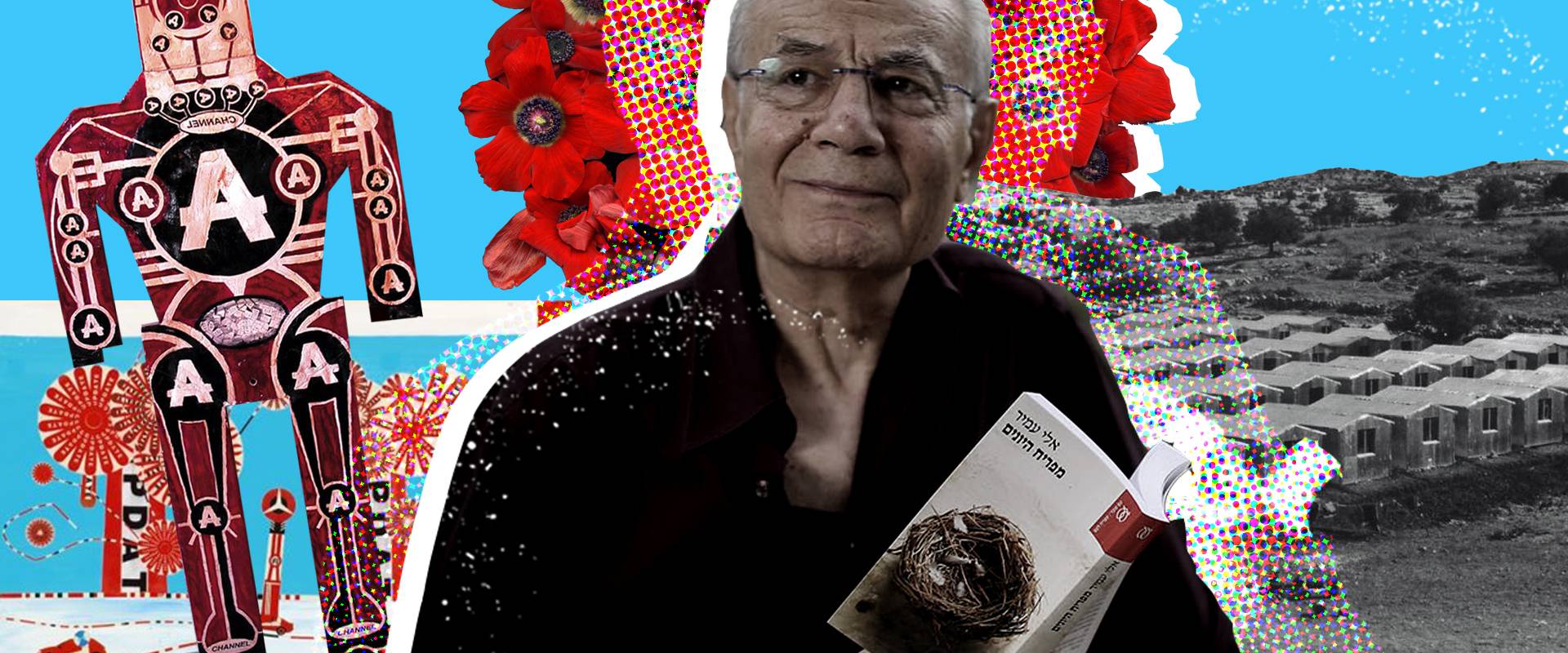

Eli Amir, Eliyahu Rips and Eliezer Sonnenschein couldn’t be more different: the first is a celebrated Baghdad-born author, the second is a brilliant mathematician from Latvia, and the third is the enfant terrible of modern Israeli art. But they are all, in their own unique ways, outsiders. Their struggle for recognition took on different forms, and enjoyed – naturally – different degrees of success. But whether it’s the hora dancing circles at Kibbutz Mishmar Ha’Emek, the pages of prestigious statistical journals, or the hallowed galleries of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, our episode explores just how far we go to feel as if we belong.

Eli Amir takes Mishy Harman back to the early 1950s, and straight into the closed world of socialist kibbutzim. Amir and his family had just come to the nascent state of Israel from Iraq, and were placed in a ma’abara, a refugee absorption or transition camp. Life there was hard, and before long, twelve-and-a-half-year-old Eli was sent off to lead a better life on a HaShomer Ha’Tzair kibbutz in the Jezreel Valley. An endless string of culture shocks followed, and the kibbutz old-timers made sure Eli never forgot he was only a yeled chutz, an ‘outside child.’ But still, Amir – who is now one of Israel’s most beloved novelists – had but one wish: to “become one of them.”

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Next month, Eli Amir will be eighty. He’s one of Israel’s most celebrated authors, he’s received many prestigious literary prizes, has a bunch of honorary doctorates, and, if they did their homework, almost every Israeli kid read at least one of his books. See, Eli’s first novel, Tarnegol Kaparot or Scapegoat in English, is assigned tenth grade reading. But despite all of that, he still doesn’t feel totally at home here in Israel.

Eli Amir: I am newcomer. I am an outsider. I was not born in the country. And, Hebrew is not my mother tongue. Whatever I do. Whatever I learn. If you want to be honest with yourself, not to play games, and to say ‘oh, of course, I am insider, the country is mine.’ No, no. I feel a bit outsider. A bit.

Mishy Harman (narration): As you can imagine, when Eli says he’s a newcomer, that’s more a state of mind than a fact. After all, he’s been here sixty-seven years. Eli was born in Baghdad. His name was Fuad Elias Nasech Chlaschi.

Eli Amir: I came to Israel at the age of twelve and couple of months.

Mishy Harman (narration): It was 1950, and like many other immigrants to the new country, the Chlaschis were sent to a ma’abara, a refugee absorption or transition camp.

Eli Amir: And the life were terrible. We saw our father’s figure walking around like shadow. They lost everything, their status, their work, their money. And it hurt me very much. Deeply. And I was very concerned. I am the oldest son in a family of nine, and I worried a lot about my father, about my family, about my sisters and brothers.

Mishy Harman (narration): He began to lose weight.

Eli Amir: And my grandmother said, “oh, kapara aleich,” in Arabic it means ‘let me go around you, to save you.’ “You lost so much weight, you look very worried, your eyes are sad.”

Mishy Harman (narration): It was decided that Eli would be sent to a kibbutz.

Eli Amir: To eat, to learn, to be in a different environment.

Mishy Harman (narration): Several months later he got his chance. A delegation from Mishmar Ha’Emek, a Shomer Ha’Tzair kibbutz in the Jezreel Valley, came to the ma’abara to recruit young immigrants. Their idea was to form a group of forty of them, all from Iraq. Eli went to the interview.

Eli Amir: They asked me, “what would you like to do in the kibbutz?” I said, “to work, to build the country.” You know, a Zionist answer. OK, of course they accepted me.

Mishy Harman (narration): Soon, Eli – who wasn’t yet thirteen – left his family.

Mishy Harman: Your brothers and sisters also went to kibbutzim or they stayed in the ma’abara?

Eli Amir: No, they stayed in the ma’abara. And you can feel the differences between them and me.

Mishy Harman (narration): Eli says he’ll never forget his first impression of the kibbutz.

Eli Amir: It was a total shock. You know, from the camps we came to paradise – buildings, quiet, afternoon, everything is so clean, even the roads. And what astonished me is that I didn’t hear any noise. It was the schlafstunde hour, at noon. And we were taken to houses, oh my god, electricity! We haven’t seen them for couple of months in the ma’abara. Wow!

Mishy Harman (narration): This was the beginning of a new life for Eli and his Iraqi friends, and the folks from the kibbutz made sure they understood that.

Eli Amir: The counselor came and he started to change our names on the spot. “What’s your name?” “Abdel Aziz.” “From now your name is Binyamin.” “What’s your name?” “Fauzia.” “From now you are Ilana.” And the children started to spell their new names. And it was no way to argue with the counselor. And he wanted to change my name. And I said “no, I would like to remain with my name.” He said, “why?” I said, “this is the name of my grandfather.” And then he said, “what your grandfather has to do with it?” I said, “he does do, ken, he does!”

Mishy Harman (narration): Everything that followed was new.

Eli Amir: We were taken at night, of course, to take shower. And we took shower with everybody. In public. A total strange culture for me. For us. So I was very shy, and I made a shower with my underwear. And then we came to the dining room. For the first time in my life, we sit in a dining room. Everybody goes there, and they see you: What you take to eat, and how much you take to eat, and how you eat, and if you know how to hold the forks and this and that. And we were very shy. We didn’t know what to do.

Mishy Harman (narration): It was there, in the middle of the dining room of Kibbutz Mishmar Ha’Emek on a hot day of early summer, 1950, that Eli made a decision which – he says – changed the rest of his life.

Eli Amir: There is a say in Arabic, that if you live with a different people for forty days, you become one of them. So I wanted to become one of them. I decided on the spot that I will do everything that the kibbutz people and pioneers are doing.

Mishy Harman (narration): That same night, Eli vividly remembers nearly seventy years later, the Iraqi kids were invited to a party with the kibbutznikim.

Eli Amir: So I saw this girls with shorts. The girls of the kibbutz, because our girls did not go with shorts. So we lost our minds, you know. I lost my mind!

Mishy Harman (narration): Everyone was dancing the hora, and Eli felt this could be his moment.

Eli Amir: So I enter the circle to hold one of their girls hand. And then another girl of our Iraqi group took courage and joined me. And then, the third one, the fourth one.

Mishy Harman (narration): But the melting pot merriment, didn’t last long…

Eli Amir: The kibbutz girls and boys left the circle. So we found ourselves on the last circle. The outsider circles, dancing alone with ourselves. And we stood back. We just look at them.

Mishy Harman (narration): You see, Eli, and all the Iraqi kids, were what what known as yaldey chutz, children from the outside world who came to the kibbutz without their parents. And, as they painfully started to realize, no matter how hard they tried to blend in, they would always be yaldey chutz.

Eli Amir: I didn’t know enough Hebrew. My accent was an Arabic accent, till now. I could never became a sabra. I could never dance the way they danced. To sing the song that they accustomed to sing. And to be part of their gathering, of their club, and belong to them.

Mishy Harman (narration): Kids are kids are kids, I guess. But here it was also wrapped up in a national ideology. One that had a very clear image of what it meant to be Israeli, and looked down on anything, and anyone, who was different. They’d call the Iraqi newcomers names.

Eli Amir: This is an Arabush, a small Arab.

Mishy Harman (narration): And make fun of their background.

Eli Amir: To be told that your culture, means the Arabic culture, is nothing, there is no culture, and all the rubbish that they are saying, and all the prejudice that they have, it was terrible. It hurts. Because we were told that by the elite of the country, and you cannot compete with the elite. You are not part of the elite, you know. And all these feelings, and thoughts, escort you on your life.

Mishy Harman (narration): Amazingly, Eli didn’t let any of it break him. Quite the opposite, in fact.

Eli Amir: I wanted to assimilate. To be one of them. I was a very curious boy, and I was lucky that my bosses in the kibbutz were like fathers to me, because they found out that I like them, that I admire them. And that I really curious to know who are they, why they came, what is their ideology. You know, till nowadays, I look up to that generation, and I admire them. I think we owe them everything we have in the country.

Mishy Harman (narration): Eli left Mishmar Ha’Emek three years later, in 1953.

Eli Amir: But it is like lifetime for me. Every moment was worth it. Every effort was worth it. Really.

Mishy Harman: With all of the trouble?

Eli Amir: With all of the troubles and with all of the difficulties. And I think that I am a very lucky person that, you know, my destiny brought me there. Yeah. It was astonishing for me. It was a miracle for me. And this a miracle that built my personality as an Israeli.

Mishy Harman (narration): So as you can hear, Eli still has mixed feelings about his kibbutz years. He was put down, time and again, as an outsider. But that outsider experience was, ironically, his ticket into the heart of Israeli society. Many years after that failed dance party, Eli started to write. His breakthrough novel, and a bunch of his other ones too, tell stories of teenage Iraqi immigrants, who – just like himself – left their families in the ma’abara and moved to closed, elitist and often unwelcoming kibbutzim. His books resonated with many people, and Eli became a famous author. At one point, in 2006, there was even a grassroots campaign to elect him president. Eli still visits Mishmar Ha’Emek from time to time. He likes to sit down with the oldtimers, the same boys and girls who used to call him an Arabush, and are now retired grandparents in their eighties. They welcome him with open arms, and Eli feels, at least for a brief moment, as if he’s at home.

Eli Amir: Because in my soul I am still kibbutznik.

Shlomo Maital delves into the world of intellectual peripheries, and asks what it’s like when your ideas are considered so far out that you lose all credibility. The unusual story of Eliyahu Rips begins in Riga, Latvia, with a radical act of political defiance. And it ends, almost half-a-century later, with a tired, if persistent, math professor fighting for academic legitimacy.

Act TranscriptEliyahu Rips: I don’t understand the whole picture not at all. I only tell you we have some drops of the ocean of information, is going here. This I can tell you. No more than this. But this for sure.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Did G-d, or whoever you believe authored the Bible, sprinkle it with secret messages? And are we just now starting to uncover their true meaning? This is a story about these questions – questions that have kept theologians, mathematicians, statisticians, journalists and politicians very busy. But at the same time, this is also a story about a man, his faith, and the lengths to which he was willing to go to stand by his beliefs.

Eliyahu Rips: My name is Eliyahu Rips. Actually when I was born I was Ilya Rips. I was born in Riga.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Riga, the capital of Latvia, was then part of the Soviet Union. Today, Eliyahu is a professor of mathematics at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University. He’s also an ultra-orthodox Jew. So picture him; He has a long white beard, payis (or sidelocks), a wide-brimmed black hat, and some blackboard chalk powder on the left lapel of his jacket. (Yes, apparently Hebrew University’s math department still uses chalkboards…). Our story begins way back when Eliyahu was still Ilya – a twenty-year-old clean-shaven student in the mathematics department at the University of Latvia.

Eliyahu Rips: In the beginning of 1968, began the so-called Spring of Prague.

Shlomo Maital (narration): The Prague Spring was a brief period of cultural and political upheaval in Czechoslovakia, while the country was, essentially, a Soviet satellite. It began on January 5th, 1968, when a local reformer, a guy by the name of Alexander Dubček, was elected to be the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

Czech documentary: Czechoslovakia has perhaps never experienced such a celebration: Free and spontaneous.

Shlomo Maital (narration): By the end of that summer, an alarmed Kremlin had sent Soviet troops to invade Czechoslovakia, putting a violent end to the democratic reforms.

[Enter ambient sounds of Czechoslovakian demonstrations]

Shlomo Maital (narration): Ilya followed these dramatic unfolding events on his shortwave radio, tuning into foreign broadcasts like the Voice of America and the BBC.

[People shouting “Dubcek! Svoboda!” and then shooting and sounds of tanks]

Eliyahu Rips: It was a very sad, very sad feeling, feeling of despair, of hopelessness, of being able to do nothing. Everything was gloomy.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Young, passionate and restless, Ilya decided that he couldn’t just sit around moping. He felt he simply had to act.

Eliyahu Rips: To express my protest about what is going on.

Shlomo Maital (narration): So he prepared a makeshift banner, and scribbled a fairly straightforward slogan on it – “I protest against the occupation of Czechoslovakia.” He then stuffed his coat and pant pockets with gasoline-soaked rags, walked over to the Freedom Statue in Riga’s main square, unfolded his banner, and spread it out on the floor beside him.

Eliyahu Rips: This was the most difficult thing I did in my life. This was a point of no return.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Then, he struck a match and set himself on fire.

Eliyahu Rips: I remember the flame on this hand and on the neck, but then I don’t remember.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Just by chance, a group of sailors passing by saw him. They threw their heavy overcoats on him, and extinguished the fire. When he regained consciousness, he was surrounded by strangers.

Eliyahu Rips: Then a person come from this crowd and arrested me, they brought me first to the Interior Ministry, then to the KGB.

Shlomo Maital: Were you happy to find that you were still alive? How did you feel about your plan failing?

Eliyahu Rips: You see, the fear disappeared.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Ilya was thrown in jail, interrogated, and charged with crimes of anti-Soviet behavior. But he wasn’t found guilty at his trial. Instead, he was simply proclaimed ‘insane’ and consigned to a closed psychiatric ward.

Eliyahu Rips: At this time, the preferred tactics of the regime was to present people protesting are insane. And actually it could be for indefinite number of years.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Fortunately for him, he had some admirers among the psych ward’s staff; people who secretly supported his protest and viewed him as a hero. He discovered this the very first morning, when he woke up to find…

Eliyahu Rips: Under my pillow, the finest kind of sucariya, Misha Kosolapi, the most expensive candy that you have in the Soviet Union.

Shlomo Maital (narration): A piece of candy, just laying there. But even more significant was the pencil that was placed right next to it. He took that pencil and wasted no time getting back to his favorite pastime: Solving math problems.

Eliyahu Rips: On toilet paper.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Yes, on squares of toilet paper in the psych ward, believe it or not, he managed to refute a famous “solution” to the ‘dimension subgroup conjecture’ – a problem that had baffled mathematicians around the world for decades. It didn’t take long before word of Ilya’s discovery reached the Western scientific community. The mystique surrounding a young and brilliant mathematician stuck in a Soviet psychiatric ward grew. Soon, an international lobby began to fight for his release.

Eliyahu Rips: The Russians did not like to have an embarrassment, so it turned out that my condition suddenly improved. The institution sent me home.

Shlomo Maital (narration): But he knew he could never fully be safe behind the Iron Curtain, so after some more pressure, Ilya and his family managed to obtain visas and…

Eliyahu Rips: In the January ‘72 we were here, in Israel.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Math had literally saved Ilya from the clutches of the Soviet psych ward, but it would ultimately lead him – as unlikely as that sounds – to even darker corners. At just twenty-three, with the eyes of the mathematical world fixed upon him, Ilya (now Eliyahu) enrolled in the Hebrew University, where he quickly finished his PhD.

Eliyahu Rips: And then I was accepted to the staff and I am… since then I am working here.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Eliyahu settled down, and everything seemed to be going his way. He got married, had kids, and spent his days teaching math. In yet another break with his Soviet past, he was also becoming increasingly religious, and began attending a daily minyan, or morning prayers. It was a mundane lifestyle, really, that is apart from being a rockstar in the combinatorial group theory scene… Then one day, as he was praying in a small synagogue in Ramat Gan, he stumbled upon a little book.

Eliyahu Rips: Chidushei Torah.

Shlomo Maital (narration): It was a compilation of drashot, or sermons, given by Rabbi Michael Ber Weissmandl, a Slovakian Holocaust survivor, to his congregants. As Eliyahu perused it, he came across a…

Eliyahu Rips: Few pages in which they recollected what he told them about his findings of skipping the Torah with equal intervals. And of course we all understand he did it without a computer. And this is just a spark of the genius.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Let me explain this whole “skipping the Torah with equal intervals” business. Suppose you pick a text, Harry Potter for example. Now erase all the punctuation marks and the spaces between the words and you end up with a very long list of letters. Then, select a certain number, let’s say seven. Circle the seventh letter of the text, skip seven again, circle the fourteenth letter, skip seven again, circle the twenty-first and so on. Finally, check to see if anything meaningful emerges from all the circled letters. That’s exactly what Rabbi Weissmandl did, and he detected what seemed to him to be messages that could not occur by chance. As he was reading about this at shul that day, Eliyahu thought to himself that it would be an interesting experiment to take Rabbi Weissmandl’s work and try to prove it, mathematically. Now, it’s important to Eliyahu that we clarify he wasn’t looking for predictions. Just statistical anomalies.

Eliyahu Rips: I looked for the first thirteen letters in the Book of Leviticus, from the word ‘Aharon.’

Shlomo Maital (narration): He wanted to check how many times that name – Aharon, the brother of Moses, appeared when skipping equal distances in Leviticus.

Eliyahu Rips: I already knew that the mathematical expectation to find is 8.3 times and it turned out that it was there twenty-five times.

Shlomo Maital (narration): So, in case you didn’t catch that, ‘Aharon’ is supposed to occur 8.3 times, but in fact, Eliyahu found, it occurred twenty-five times. The probability of that happening by accident, randomly, was nearly zero. Eliyahu was dumbfounded.

Eliyahu Rips: Unforgettable moment. I became convinced that this could be studied by scientific means.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Following that initial surprising find, Eliyahu went on to devise a more comprehensive experiment – he picked thirty-four prominent rabbis, and checked how many time, using the equidistant-letter-spacing method, their names showed up in the Book of Genesis. He then compared that number to what he would have expected to find, statistically-speaking. Separately, he also looked into whether the occurrence of those rabbis’ names in the text happened to be next to a stretch of letters that corresponded to their dates of birth and death. Eliyahu and his two research partners – Doron Witztum and Yoav Rosenberg – discovered uncanny correlations between the names and the dates. The math involved is extremely complicated, but the bottom line was that this was really, really, unlikely. In any event, they wrote up their findings, and submitted their paper to a well-respected journal called Statistical Science.

Eliyahu Rips: I had a conviction that science looks impassionate search for truth.

Shlomo Maital (narration): The paper ended up on the desk of the journal’s editor, Robert E. Kass, a famous statistics professor from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. He was completely baffled: On the one hand, he didn’t believe it for a second; the entire idea seemed utterly preposterous. But on the other hand, he couldn’t find a single methodological or computational flaw in the draft of the article. Not knowing what else to do, he sent out the paper to independent peer-reviewers. He was certain they would quickly point out the errors, debunk the argument, and then he could scrap it in good conscience. End of story. But the thing is… they couldn’t! So Kass brought in his senior editors for a consultation. Here he is.

Robert Kass: One person in particular argued strongly against publication. He effectively predicted exactly what would happen. And I decided that, for the benefit of the field of statistics, we should publish it.

Jordan Ellenberg: They published it, quite unusually, with a kind of editorial note at the beginning of that issue of the journal saying, “you know, we’ve published this as kind of a challenge to our readers. This finding seems bizarre, we don’t really believe it, but you know we’re scientists, this study was carried out in accordance with like usual practices, and so it wouldn’t really be fair not to publish it, but just so you know, we think it’s weird.’

Shlomo Maital (narration): That’s Jordan Ellenberg.

Jordan Ellenberg: I’m a professor of mathematics here at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Ellenberg, who devoted a whole chapter to Rips and the Bible Code in his latest book, ‘How Not To Be Wrong’, is actually the one who got us onto this whole saga. Back in 1994, when the article came out, Ellenberg was in graduate school.

Jordan Ellenberg: My initial reaction was the same as that of a lot of people, which was that something must be wrong with this.

Shlomo Maital (narration): And Ellenberg wasn’t alone.

Jordan Ellenberg: It became a huge craze in the United States. This idea that there were secret messages, I mean people here in the US are pretty interested in the Bible as it is, as you know. And even more so, right, when there’s kind of fascinating secret messages which foretell the future.

Shlomo Maital (narration): One of those who jumped on the ‘Rips bandwagon’ was an American journalist by the name of Michael Drosnin. In 1997, he published a book titled ‘The Bible Code,’ which took Eliyahu’s statistical observations one, crucial, step further.

Michael Drosnin: I found encoded in the Bible a prediction of the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin a year before he was killed.

Shlomo Maital (narration): This was precisely what Kass’ editors had feared. That quasi-scientists and non-academics would take the finding they had published and run with it in all kinds of crazy directions. This is Drosnin talking to Charlie Rose on PBS:

Michael Drosnin: I immediately flew to Israel, I gave this in a letter to a close friend of the Prime Minister, a poet named Haim Guri, who had known Rabin since childhood and won Israel’s two top literary prizes. And I said please give this to your friend. I don’t know that he is in actual danger but I do know that his assassination is very clearly encoded, and if I were him I would take this very seriously because the Bible code also details the assassinations of both Kennedys and Anwar Sadat.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Drosnin, quite simply, was using Eliyahu’s methods (or at least his version of them) to predict the future, and his predictions were making the rounds. The media was loving it…

TV ad: Every major event in world history… [Goes under].

Shlomo Maital (narration): And the general public was eating it up.

TV ad: Appears to be encoded in the Bible… [Goes under].

Shlomo Maital (narration): Drosnin’s book made the New York Times bestseller list and even Oprah invited him to appear on her show.

TV ad: [German]. The code that tells of events far in the future. We might face the real armageddon. [Spanish].

Shlomo Maital (narration): In all his media appearances, Drosnin made sure to mention that his book was based on a ‘major publication’ – that is, Eliyahu Rips’ article. While Drosnin’s ‘Bible Code’ was selling like hotcakes, the scientific community was mortified. My favorite demonstration of that embarrassment comes from mathematician Dave Thomas who worked hard to find his own secret message encoded in the Bible: “The Bible code,” it read, “is a silly, dumb, fake, false, evil, nasty, dismal fraud and snake-oil hoax.” But while Drosnin could be dismissed as a crackpot, mathematicians around the world were still enthralled, and confused by Eliyahu’s seemingly rigorous, and robust publication. One of them was all the way over in Canberra, Australia.

Brendan Mckay: I’m Brendan Mckay, I’m just retired as a computer scientist at the Australian National University, and I specialize in combinatorial mathematics and probability theory. When I first heard about these claims, I was excited because I’ve had, as a sort of hobby, the debunking of claims like this for a very long time. But because Rips is such an excellent mathematician, and because the paper they published was written so carefully in order to not expose the weak points in their case, it was quite a difficult debunking task.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Mckay wasn’t only intrigued, but also spurred to action. He spent a long time trying to refute Eliyahu’s claims, and he didn’t get very far. At the same time, and on the other side of the globe, a group of Eliyahu’s own colleagues from the Hebrew University were also working on a rebuttal. They had heard of Mckay’s efforts, and decided to give him call. They said…

Brendan Mckay: “Look, we’re working on this too, why don’t you come to Israel, we’ll work on it together?” And that’s how I got started.

Shlomo Maital (narration): It took them three years, but eventually another paper appeared in the same journal – Statistical Science. The joint Aussie-Israeli team basically replicated Eliyahu’s experiment, with one major difference.

Brendan Mckay: The famous experiment of Rips and his coworkers compared names and dates of birth and death of famous rabbis from Jewish history in the text of Genesis. We did the same thing in the text of War and Peace, and we “proved” (where the word “proved” is in quotation marks) that War and Peace predicted these correspondences between these rabbis and their dates of death.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Basically, they showed that these statistical anomalies could exist in any long text. That the Bible did not, as many people thought Eliyahu’s research had shown, contain a secret code. Almost overnight Eliyahu went from being a well-respected member of the academic community to being a derided and ridiculed mathematician.

Eliyahu Rips: We were buried. So it seemed, so it seemed.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Now, while Mckay and company merely claimed to uncover flaws in Eliyahu’s scientific method, others went so far as accusing him of intentionally falsifying the data, by cherry picking the names that came up with the best correlations.

Robert Kass: I would not have called him a charlatan. I would have not have called him a fake. I don’t… I didn’t question his motives. It’s just that it never surprised me that he got this wrong. Or, at least, I think he got it wrong.

Shlomo Maital (narration): That’s Robert Kass, the journal’s editor, once again.

Robert Kass: So I… I never thought that, you know, he was deliberately distorting things. That wasn’t the point. The point was actually a more important one. Because someone who really means well and believes in what they’re doing can make a very basic mistake.

Jordan Ellenberg: This is really a con you can pull on yourself.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Here’s Jordan Ellenberg again.

Jordan Ellenberg: You can fool yourself without being a sort of evil person who is trying to fool other people. They wanted this to be true. And that’s the hardest kind of con to defeat – the one they run on yourself.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Despite his tarnished reputation, Eliyahu still believes he’s right, and that he’s onto something so big, so incredibly huge that people have a hard time accepting it. Eliyahu thinks that the statistical anomalies he unearthed can only be explained by the fact that the Bible was written by G-d. A G-d who knows the future. But down here, in the terrestrial world of math and statistics departments, his claims have been regarded as somewhere between wrong and fraudulent. And this is, he says, an accusation more painful, more paralyzing, than setting himself on fire. For the last twenty years he’s been trying to publish another paper responding to the allegations leveled against him with further proof of his Biblical correlations.

Eliyahu Rips: The journal did not allow us to respond.

Robert Kass: So in principle, I think it would be reasonable for them to absolutely to consider such a letter.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Robert Kass is no longer the journal’s editor, but he agreed to answer my hypothetical.

Robert Kass: I have to tell you I have trouble imagining what he could say that would materially change anything. And the very fact that he continues to believe it, that’s not publication-worthy.

Shlomo Maital (narration): In many ways, Eliyahu feels that this state of academic shame is worse than the Soviet prison or the closed psychiatric ward.

Eliyahu Rips: I must say that somehow, maybe because then I was young, I didn’t feel it scratch me. And here, this controversy, was a real suffering. You see there was a saying in the Soviet Union. To be in prison is difficult only for the first ten years. So I am kind of the intellectual prison, just I have to do what I can do, that’s all.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Still, despite the entire firestorm, Robert Kass doesn’t regret publishing Eliyahu’s paper. That’s just how science, and knowledge in general, advance, he told me. People put their ideas out there, and others scrutinize them. Many new ideas will get shot down. But once in awhile an idea will stick, and generate new ideas.

Robert Kass: Is society ultimately served by this process? Yes it is. Because people will come to appreciate all of these subtleties, they will come to appreciate even better that it’s hard to be sure or to be confident about patterns in complicated data and what they mean. And that’s the ultimate lesson of the story, that there is subtlety there and you have to be very careful.

Shlomo Maital (narration): But Eliyahu doesn’t agree. For him it’s not about subtlety or an evolutionary process of natural selection of ideas. As far as he is concerned, it’s a story of a misunderstood scientist who made an astounding discovery, one his peers were too scared, or too reluctant to acknowledge. In the meantime, stuck in an academic limbo, Eliyahu continues to do the exact same thing that helped keep him sane back in the Soviet psych ward. Math. I met up with him a couple of times to record his story. And at the very end of our last interview, Eliyahu excitedly pulled out a thick binder from his briefcase and handed it to me.

Eliyahu Rips: Here is some new thing that was done by Doron Witztum and curiously I obtained this paper just this Friday.

Shlomo Maital (narration): As he told me this he had a big smile on his face, and seemed almost radiant. Eliyahu and his long-time research partner, Doron Witztum, had recently made some new discoveries.

Eliyahu Rips: He had the following idea.

Shlomo Maital (narration): It could, he said, be big.

Eliyahu Rips: This is extremely important new data. It overturns the table on this discussion, It surely deserves a major publication, at least you have found me at this point, I still did not lost the hope.

Shlomo Maital (narration): Eliyahu Rips, you see, is far from giving up.

Eliyahu Rips: Who knows. Let us hope.

Long before Banksy became a mysterious international star, Eliezer Sonnenschein from Haifa was being called an “artist/terrorist.” Zev Levi enters the heart of staid art institutions, and brings us the tale of one man who decided he would go as far as he possibly could to leave his mark.

Act TranscriptZev Levi (narration): Back in the ‘90s, Eliezer Sonnenschein from Haifa would routinely sneak into museums and art galleries. But he wasn’t a thief or a vandal. He wasn’t even trying to avoid paying the entry fee. You see, he thought he belonged there. With a ponytail and all the confidence that comes from being in your twenties, he was certain that…

Eliezer Sonnenschein: I’m very talented. Very talented. My mother says to me that I’m talented.

Zev Levi (narration): Eliezer saw himself as a respectable artist and was convinced that museums should exhibit his work. He approached the who’s who of curators and gallery owners – the gatekeepers of the art scene – and… was promptly rejected. Without a degree in art, they didn’t know him and weren’t impressed. But Eliezer wasn’t phased; asking their permission was only one option.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: I looked at the museum as a space. And kind of a communication.

Zev Levi (narration): That space, he thought, should be open to everyone. Regardless of what the “experts” believed.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: One of the things that I loved to do is to open the catalogue that the museum send you and to see what new exhibitions are coming, and to decide in what exhibition I will exhibit.

Zev Levi (narration): So, one day in 1995, this self-proclaimed virtuoso quietly waltzed into someone else’s exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. He was armed with a concealed package. His heart was racing so fast, he could barely think straight. He walked the halls alongside the unsuspecting public, hoping they couldn’t hear the thumping inside his chest. And then he saw his chance. In an unobserved flash, he crouched down and added a homemade piece of art to the collection – a glass bottle painted stark black, white, and red.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: From the first bottle that I laid down on the floor on the museum, I knew that in two years, I’m going to be much more bigger than that.

Zev Levi (narration): Eliezer was high on adrenaline: He was actually exhibiting in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art! To bask in his glory, he returned the next day and checked on his piece. It was standing proud. He came back the day after. And the day after that. And the day after that. His bottle lay untouched, gathering dust, on the floor by the wall. He wondered whether anyone had even seen it. Finally, one day, he saw it was gone. Eliezer breathed a sigh of relief. He knew exactly what to do. He called the museum and yelled at them. How dare they remove art from an art exhibition? Who were they to decide what belonged there? In no time at all, Eliezer retaliated: He planted a new bottle in the same place. This cycle was repeated several times. And each time Eliezer snuck in some of his work, he gained energy. He gained a purpose. He gained a direction. And he started hatching a bigger plan. A few days after a new show opened, Eliezer called the museum and impersonated the curator. As the curator, he told the museum staff that an important artist was coming in directly from Europe, and that they shouldn’t get in his way. Thirty minutes later, Eliezer called again, this time as himself, that is the ‘important artist from Europe.’ He casually liaised with the staff about how they could help him arrange his artwork. Later that day, he was already drilling a hole in the museum wall and hanging up his art.

Zev Levi: When you were setting up your pieces, did you feel like you were forcing a place for yourself in the art world?

Eliezer Sonnenschein: It was my place already.

Zev Levi (narration): Before too long, museum officials realized that they’d been… hacked.

Itamar Levy: I just got a call from the museum.

Zev Levi (narration): That’s Itamar Levy, the curator that Eliezer had impersonated.

Itamar Levy: They asked me if a certain work is part of the exhibition which I had curated. And I said “no, it’s not.” “What shall we do with it?” I said, “remove it.” And I didn’t know who put it there. I didn’t know what it was about. I didn’t give it a second thought.

Zev Levi (narration): Itamar felt that his exhibition had been hijacked.

Itamar Levy: You think, when you position work in the museum, about every detail. How it will look from every angle, what other artists will be the background. You know, you have so many considerations. And they suddenly… You know, they are the ones who suffer from this proximity to a work that was not invited.

Zev Levi (narration): An irate Itamar immediately called the infiltrator.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: He was furious. After he found out that I planted my stuff in his exhibition. And he shouted, I’m doing shit, I’m a shit artist and all this stuff.

Itamar Levy: Yeah, you are a saboteur, you sabotage the authority of the museum. You can fool the museum, but the bottom line is that you want to join the party.

Zev Levi (narration): Unsurprisingly, Eliezer’s work was removed.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: And the day after, I put another thing in the museum, just to show them that it’s my game.

Zev Levi (narration): This time it was a wad of bills, made of plaster. To Eliezer, the whole episode was…

Eliezer Sonnenschein: Some kind of a dance that I’m doing with the museum. The museum was furious. I was great. They were playing to my hands.

Zev Levi (narration): And Eliezer was just getting into the swing of things. As the dance of the guerrilla artist and the guards continued, word of his clandestine tactics and invasive approach began to spread.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: So they call me a terrorist.

Zev Levi (narration): But it turned out that Eliezer had some sympathizers on the other side.

Ellen Ginton: Well, it’s terror on a very symbolic level.

Zev Levi (narration): This is Ellen Ginton, a curator at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Ellen remembers…

Ellen Ginton: Just strolling in the museum as I used to do. And there was an object. Black, red, and white. A beautiful robot.

Zev Levi (narration): She was struck by the crude style and materials, by the aggressiveness of the piece. To her, the robot looked like…

Ellen Ginton: Outsider art.

Zev Levi (narration): Outsider art. Art made by people who aren’t members of the closed world and elite circles of art institutions. She says she didn’t really know what the piece was, but she found it very interesting nonetheless.

Ellen Ginton: And the next day it was gone. I asked what was it, by whom was it? And I was told that somebody smuggled it in and planted it in the exhibition and the curator didn’t receive it well and he asked for it to be removed, and it was removed and I never saw it again.

Zev Levi (narration): Shortly afterwards, during one of Ellen’s own exhibitions, she also got a call from museum security, just like Itamar had.

Ellen Ginton: I was called by our guards, “come please! Please do come! Somebody left some shit in your exhibition.”

Zev Levi (narration): Those guards weren’t just being vulgar. This time, Eliezer had dropped off sculptures of… feces.

Ellen Ginton: And I ran downstairs to the exhibition and I saw beautiful sculptures on beautiful boxes with commercial logos, a Barilla pasta, Marlboro cigarettes, black, white, and red, a very intensive red.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: Pieces of shit. They were all made of plaster. And I concealed them behind statues. They were very nice. And it was beautiful because you could see people walking and then looking behind the statue and starting to laugh and something like this.

Zev Levi (narration): Just like many of the visitors, Ellen got a kick out of it.

Ellen Ginton: I thought that, if the artist will identify himself, the sculptures remain because it’s beautiful and it’s ingeniously placed.

Zev Levi (narration): Alas, only months after he began his symbolic terrorism, Eliezer paid the ultimate price for being counter-cultural; the art world started embracing him.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: I got a phone from Ellen. I wasn’t into calling her back because I didn’t felt like being shouted again. And then I get a phone call from another friend that knew her. And he told me, “it’s OK, call her.” I called her and she likes it and she put a real label – like a museum label. It felt like the new era had just came flashing down.

Zev Levi (narration): That was 1996. But being accepted by one good-natured curator by no means meant that Eliezer was now on the inside. Two exhibition-less years later, in 1998, Eliezer caught wind of an upcoming show: “Ninety Years of Israeli Art.” That title really bothered him. How could a comprehensive history of Israeli art not include… him? Eliezer decided it was time to take his guerilla-art tactics to the next level. The night of the grand opening, Eliezer milled around the museum, blending in with the swarm of guests. He waded through the crowd, making his way to the bathroom, where he transformed. He changed into clothes that were completely black, he donned a black face mask, and assembled a four-and-a-half-foot-long sculpture made of plaster and covered in product packaging and news media logos. The piece was an overload of black, white, and red, and had the shape of a rifle. The barrel bore the words…

Eliezer Sonnenschein: Fuck Claudia Schiffer.

Zev Levi (narration): Apologies to nineties supermodel Claudia Schiffer. Exiting the bathroom, the dense crowd scattered before him as if he was a disease. They weren’t afraid, exactly. It was totally clear that his oversized “gun” was just a prop. But still, they all realized that something odd was going on. Imagine you’re at a business meeting, and someone dressed as Chewbacca walks in and sits down. It’s not threatening. It’s just bizarre and disturbing. Anyway, while the museum director addressed the packed room from a podium, Eliezer sidled up and stood directly behind him, in full view of everyone. After the speech, Eliezer himself took the stage. And stood there. Holding his corporate “rifle” in the air. It may be difficult to understand why anyone would let this masked figure with a toy gun get on stage. An easier question may be who, at an art gallery, would want to get in his way. By the time a member of the Shabak – Israel’s national security agency – whispered to him, “hey buddy, you’re making the organizers nervous,” Eliezer was ready to leave. He had accomplished what he had set out to do: Leave his mark on one of the ninety years of Israeli art. Eliezer was, in every way, an artist-terrorist.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: I wasn’t really a terrorist. You know, it sounds great because everybody calls you an artist terrorist, so you’re an artist terrorist but really it’s like a dog going into a chicken coup. I mean like, is he a terrorist? No he’s not a terrorist. He just went inside. I really don’t give a shit. I’m just doing what I like to do and I will continue doing it until the lights go down.

Zev Levi (narration): But that gun-toting appearance was the last time Eliezer infiltrated an exhibition. After that, there was no real need; museums were asking him to put on solo exhibits and he was gaining an international reputation. Just a few short years later, in 2001, he represented Israel in the prestigious Venice Biennale. Yet throughout his career, he told me, nothing felt as exhilarating as planting his first bottle on that museum floor. Presenting solo international shows doesn’t even come close. Eliezer remains proud of the way he broke onto the scene. He believes that artists should control art spaces. Though he always felt that the high echelons of the art world were his rightful home, his natural habitat, his domain, he doesn’t really feel at home with his neighbors there. To this day, he still has to work with all the people he offended with his antics – people who still think he doesn’t belong.

Itamar Levy: We know there are people that are sophisticated people and there are vulgar people. There are people who are just about power and there are people who are committed and have responsibility.

Zev Levi (narration): For the record, Eliezer – the outsider who’s now on the inside – is not interested in patching things up.

Eliezer Sonnenschein: I’m Israeli macho sabra artist. What can you expect from me? Maybe if he’ll go to Sweden, he will find other artists. But being in Israel and looking for Swedish art is stupid.

The original music in ‘Skipping the Torah,’ was composed and performed by Ruth Danon. The final song, “Yeladim Kamonu”, is by Elai Botner and Yaldey Ha’Chutz. The episode also features music by Karolina, Tristan Lohengrin, Dana Boulé and Robert Schumann. It was edited by Julie Subrin and mixed by Sela Waisblum and Aviv Meshulam.

Thanks to Daniel Estrin, who did the original recordings for the Sonnenschein story, to Charles Monroe-Kane, Caryl Owen and all our friends at TTBOOK, to Prof. Hillel Furstenberg, to Ran Tal and to our beloved Eve Sneider and Dima Perevozchikov.

Amazing Journeys is a travel company offering group trips for Jewish Singles. Indulge your passion for discovering new destinations with like-minded travelers from around the world. They take the guesswork out of vacation planning, so all you have to do is sit back, relax and enjoy the journey!

Amazing Journeys is a travel company offering group trips for Jewish Singles. Indulge your passion for discovering new destinations with like-minded travelers from around the world. They take the guesswork out of vacation planning, so all you have to do is sit back, relax and enjoy the journey!

Get $100 off your first amazing journey with the code Israel Story.