This Thursday, May 5th, Israelis observe Yom HaShoah, or Holocaust Remembrance Day. At 10 a.m., according to custom, an air raid will sound and the country will fall quiet for two long minutes. Silence won’t do for a podcast, so instead we bring you two stories.

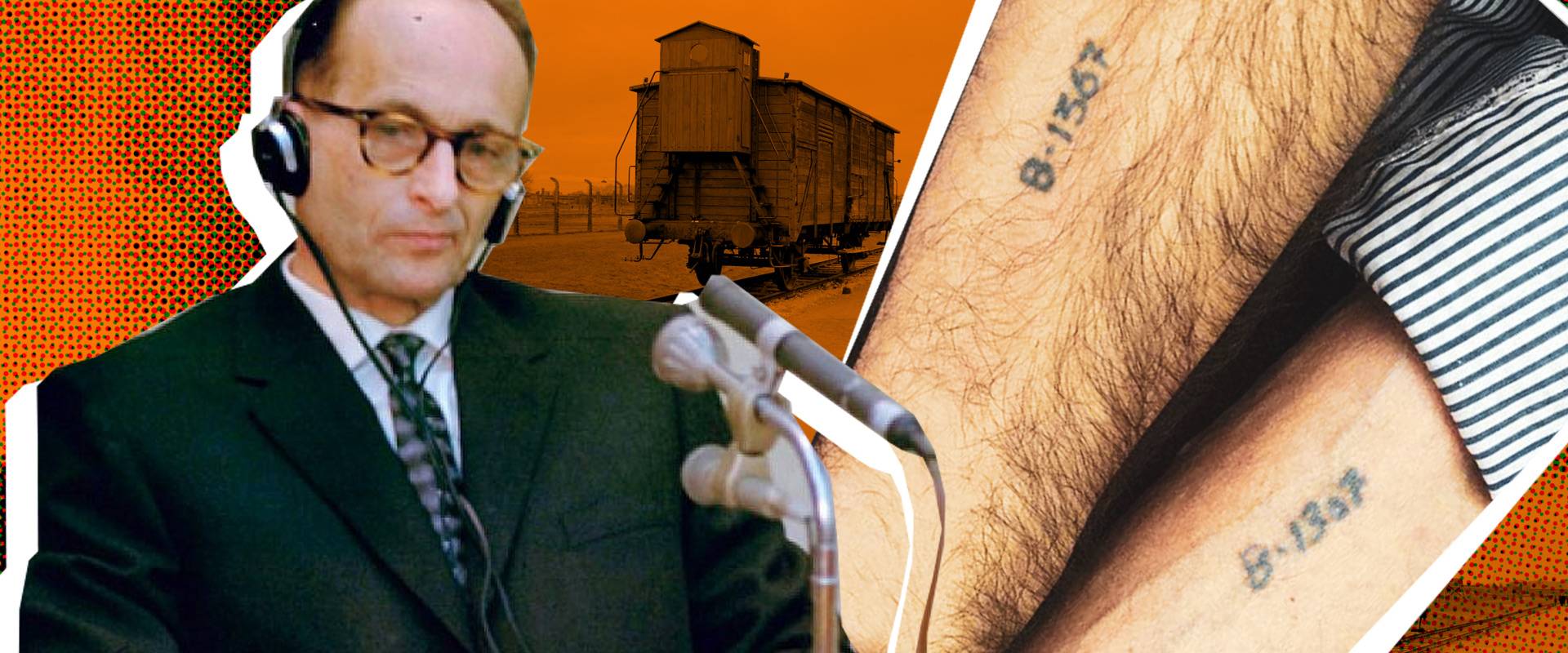

Our first story, “B-1367,” is about an elderly father and his 53-year old son, and the inked number that binds them.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): Walking into Ahuva and Yeshayahu Folman’s flat, on the eleventh floor of a white, modern-looking apartment building in Rehovot, is like stepping into another era. When I got there, together with their son Ron – an ex fighter-pilot in the Israeli Air Force – the mom, Ahuva immediately guided us to the dining table. Before I could say that I had already eaten, she placed a bowl of chicken soup with matzo balls in front of each of us. That was soon followed with a full plate of kasha, fish, tzimmes and boiled squash. For dessert, and mind you this all happened within the span of about ten minutes, we each got a small serving of applesauce. So classic. Only some fruit compote was missing to make it the quintessential Polish mama experience. After we finished we rolled into the living room and started chatting. It was well after 2pm, but eighty-two-year-old Yeshayahu said it was OK, that he’d postpone his schlafstunde, his afternoon rest, till a bit later. When you look at Ron and his Dad, you immediately notice that they look a lot alike: The same wide-bridged nose, the name bluish-gray eyes, same high forehead. And then, there’s this other thing they have in common.

Ron Folman: So the number I have on my hand is B-1367.

Yeshayahu Folman: And I have the same number – B-1367.

Mishy Harman (narration): The two men roll up their sleeves and show me their left forearms. Yeshayahu’s looks like that of an old man: Fragile, a bit saggy, with paper-thin skin through which you can see many blue veins. Ron is fifty-three. His arm is stronger, and covered with dark hair. Yeshayahu’s tattoo is faded. Ron’s, on the other hand, is sharp. But other than that, and a small difference we’ll get back to later, they’re completely identical. The circumstances in which they got them, of course, couldn’t have been more different.

Yeshayahu Folman: I remember vaguely getting my tattoo. We stood in the queue. I remember two small tables and two people behind their tables doing tattooes to people and at the same time also making notes on small cards. This was in Birkenau. I was then ten-and-a-half years old. Birkenau, as you know, was part of the Auschwitz Complex.

Mishy Harman: Ron, can you describe getting your tattoo?

Ron Folman: Well, I was in my thirties, somewhere in the middle of Tel Aviv, I don’t remember exactly where. I just sat down in front of a tattoo artist who was shocked by the request. He is used to making birds, and flowers and animals and suddenly he’s asked to make a number, and it’s not a telephone number of some nice girl. And, ahhh… and he did it!

Mishy Harman (narration): Ron got his tattoo in the year 2000, right after handing in his physics PhD. It was almost exactly fifty-six years after his father had gotten his.

Mishy Harman: Did getting the tattoo hurt you?

Yeshayahu Folman: No, no. It did not hurt. No… I don’t think this bothered me at all. There were other things [laughs] that bothered me more like what to put in my mouth, I guess. [laughs].

Mishy Harman (narration): Yeshayahu survived the Holocaust. That’s a whole other story. He ended up in Israel, in the Ben-Shemen Youth Village. He began attending night school.

Yeshayahu Folman: This was the first time when I went to school, at the age of thirteen.

Mishy Harman (narration): And that was also where he met a girl, who had originally come aboard the Exodus.

Ahuva Folman: Well, I’m Ahuva (Luba) Folman-Gordon [laughs]. And was born in 1934 in Minsk, in White Russia. We hardly got away from the Nazis. I met Yeshay in evening school of working youth. We worked during the day, we studied during the night.

Mishy Harman (narration): The two teenagers fell in love. They got married, moved to Rehovot, had three kids. Ron is the middle child. They’ve been together for more than six decades, but still look at each other as if they’re on their first date. And all those years, Yeshayahu – who ultimately became a biology professor at the Hebrew University, and the Chief Scientist of Israel’s Ministry of Agriculture – never tried to hide his past, or his number.

Yeshayahu Folman: I don’t remember any occasion that I was ashamed of the number, or that I was trying to hide [laughs] the number, or anything of like it. Nothing of the sort. Nothing.

Ahuva Folman: We tried to be normal parents, and the children should have a normal childhood and everything. But of course in the background they always felt, and they knew, what their father went through. So, it’s always in the background.

Yeshayahu Folman: We behave absolutely normally in everyday activities, in everyday expression of feelings. We don’t remember, or talk about, or remind ourselves of the Shoa. This is the main success, that you are able, after all that’s happened, to live a normal life.

Mishy Harman (narration): But like in many families, despite the attempt to move on and live a normal life, there was an underlying sadness that the kids were all aware of.

Ron Folman: As a child, I remember no signs of pain from my father. And, the only signs I could ever see was almost a hidden, a secretive teardrop coming out of his eye, without any words being spoken, when he was watching some movie about the Holocaust. So that was very rare but that was the only sign I remember for many many years to what was really going on inside him. And I think he himself was even living until quite a late age in denial.

Mishy Harman (narration): It took Yeshayahu a long time to even acknowledge that the War had left its mark on him.

Yeshayahu Folman: Until the age of thirty-five, I was absolutely sure that the Shoa did not affect me at all.

Ahuva Folman: He was just rejecting the thought that it is in any way has affected him.

Yeshayahu Folman: But one day I saw a photo, and I decided, good God, this guy has depression. Myself I mean [laughs]. And that must come from the Shoa.

Mishy Harman (narration): None of the Folmans remember the first time Ron asked about his Dad’s tattoo. But they all remember the day he told them he wanted to get one of his own.

Ron Folman: It was, I could say, a very personal decision, not as some demonstration, or as some message to the world that I’m strong and I’m here and I survived, but a very personal message to my father. At that time my father was very ill. He was in a hospital. I had the feeling that we will soon say goodbye. And I felt that I have to convey some kind of message of love, of solidarity, of understanding, to him, and I felt that words are just not enough. And so at that moment I decided that I would like to make this tattoo.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yeshayahu and Ahuva couldn’t really understand Ron’s gesture.

Yeshayahu Folman: We expressed our total objection to it [laughs]. We don’t want that his daughters, the next generation, will feel the burden of the Shoa.

Ahuva Folman: I objected to it, totally, as well.

Yeshayahu Folman: I felt that this is too much of a sacrifice, on the part of Ron, towards myself.

Mishy Harman (narration): But Ron was determined.

Ron Folman: I decided to do it anyway, I am sometimes a very stubborn person.

Ahuva Folman: [laughs] But we are also getting along with it, we had to accept it. He is a grown person, and that’s what he decided, so we had no choice.

Mishy Harman (narration): He knew exactly what he wanted.

Ron Folman: I wanted it to be very accurate, in terms of color, and position on the hand, and the exact numbers and letters.

Mishy Harman (narration): And since nothing could be a better stencil than the original, Ron, Ahuva and Yeshayahu found themselves stepping into a dingy tattoo parlor in the middle of Tel Aviv. Ahuva, a dentist, was worried about the sterilization of the equipment, so she went inside with Ron. After showing the tattoo artist his arm, Yeshayahu waited outside. It must have been surreal for him. Here he was, in the middle of a Jewish city in a Jewish state, waiting as his son, a fighter-pilot in the Israeli Air Force, got the the same tattoo that had been forced upon him, more than half a century earlier, in Birkenau. When it was all done, and the newly tattooed Ron came out, they all noticed the tattoo artist had messed up. Nothing major, but just a little bit.

Ron Folman: He didn’t do it perfectly, unfortunately. The letters and the numbers are correct, and the position, and the color, are perfect, but the number three that my father has is completely circular, and the number three that I got, ahhh… the top of the number three is flat.

Mishy Harman (narration): I asked Ron why that mattered to him. He said he’s a scientist, and that accuracy has always been a big part of his life. This tattoo, he continued after a short pause, needed to be accurate too, because it represented a memory. A memory of what went on back then. And memories, Ron thinks, memories should be precise. Sixteen years have passed since that day. Ron has made his peace with the straight top of his number three. Like his Dad, Ron also became a professor, at Ben Gurion University in the Negev. He got married, divorced, remarried. He has four daughters.

Mishy Harman: So, Ron, if your daughter came to you and said, “I want to also have the same tattoo,” what… what would you say?

Ron Folman: Well, ehhh… she did indeed come when she was sixteen (she’s now eighteen) and said that she’s going to make this tattoo on her hand. And I gave her, straight away, the exact same response my parents gave me, and that is an absolute no. But she is a free, independent individual, what she does is up to her, it’s her decision. But my answer to her was very clear.

Mishy Harman: Why?

Ron Folman: For the exact same reasons that my parents told me not to do it. And that is that they wanted their children, and I want my children, to have a happy childhood, happy life, as much as possible in this world. And not to carry on them, on their back, the burdens of pain of previous generations.

Mishy Harman: So she didn’t do it yet?

Ron Folman: No, she didn’t do it yet.

Mishy Harman (narration): Before I left Ahuva and Yeshayahu to their afternoon naps, and returned to a life in which you don’t get a small serving of applesauce at the end of the meal, I wanted to know what they all felt, now, about this larger-than-life homage.

Ron Folman: Ehh… Actually, after I did the tattoo, and for many years since then, many people come to me, or write to me, from many different places. And some of them say that it’s the most horrible thing that I did, and that I’m letting the Nazis win all over again. And some of them say exactly the opposite. They say that here I am, the next generation of the Jewish people. I am strong. I am educated. I have my own country. And I am free to choose whether or not I put this number on my hand.

Ahuva Folman: Of course Ron wanted to do this tattoo as a great great homage to his father, to show his love and devotion and all that goes with it. That’s wonderful. That’s more than you could expect from a loving son. But I think something from inside also wanted to declare Am Yisrael Chai. I think so. He doesn’t think so, but I think he felt it.

Ron Folman: Eh, I don’t consider it to be a victory over the Nazis or victory by the Nazis.

Mishy Harman (narration): At this point, Yeshayahu nodded his head, and put his hand on his son’s arm, just above the number.

Yeshayahu Folman: I don’t see a victory, I don’t see it a defeat [laughs], I see it a message from Ron, to myself, and eh… I feel a little… a bit awkward even now [laughs] that he did it. But what can I do? Here I am, he did it, and that’s it. You have to accept the facts of life. This is one of them.

Mishy Harman (narration): Our second story today takes us back in time to a very different Israel. One in which the Holocaust was still a shameful topic, that wasn’t really discussed much. European Jews, many Israelis felt, had gone to the camps like lamb to the slaughter, without resisting, without a fight. That began to change, as a result of one event. One event which still, in some very real way, shapes Israel today. On May 23rd, 1960, just as most of the citizens of Israel were waking up from their afternoon naps, Prime Minister David Ben Gurion made a dramatic announcement in the Knesset.

[Ben Gurion speaks in Hebrew]

In Act II, “Herr Eichmann,” we meet up with a group of men for whom Eichmann is not a symbol of Nazi evil, but a gaunt, balding prisoner for whom they were responsible, as guards and interrogators.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): “A while back,” he told the nation, “the Israeli security services discovered one of the greatest Nazi war criminals alive, Adolf Eichmann. Along with other Nazi leaders, Eichmann was responsible for what they called the ‘Final Solution’ for the Jewish problem, the extermination of six million European Jews.”

Ben Gurion then paused for a second, and delivered the bombshell: “Adolf Eichmann,” he said with excitement, “is now in custody in Israel and will soon stand trial in Jerusalem.” Now, we all know about the Eichmann trial. You can probably even conjure up the famous image of a balding, thin middle-aged man, responsible for the deaths of millions of Jews, sitting inside a glass booth in the Jerusalem courtroom. Many of us have learned about the trial in school, or watched documentaries about it on Holocaust Remembrance Days, or read Hannah Arendt’s “Report on the Banality of Evil,” or a zillion other accounts of the saga. And, just in case none of this sounds familiar, the Israeli National Archives have recently uploaded videos of the entire trial to YouTube. Eichmann has become a symbol. A symbol of evil. But for today’s show, we decided to seek out members of a dwindling group of Israelis who remember Eichmann not as a symbol, but rather as a man. A man with a name.

Shai Inbal and Katie Pulverman met up with people for whom the encounter with the Nazi officer wasn’t just a moment of national catharsis. It was an intimate experience. Maybe even too intimate.

Amram Lusky: I was twenty-seven at the time, and I was serving in the Border Police.

Katie Pulverman (narration) That’s Amram Lusky. Today he’s an eighty-two-year-old retired grandpa of five, who likes to pickle vegetables. But in 1960 he was a young cop, chosen for a very sensitive task.

Amram Lusky: One day I was summoned to the police national headquarters and was interviewed by Amos Ben-Gurion, the Prime Minister’s son. He was actually the one who chose me. I remember Amos just said, “you will be a part of this team.”

Katie Pulverman (narration): Amram had no idea what team he was joining. All he knew was what he had been told.

Amram Lusky: As of today, you belong to a special unit, which doesn’t even have a name. Tomorrow morning you’ll report for duty, and you’ll tell your wives that you don’t know when you will be back home.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Amram agreed.

Amram Lusky: Then, in one night, we made an entire prison made for one prisoner.

Katie Pulverman (narration): The next day, when he heard who it was he would be guarding, Amram wasn’t too impressed. He had emigrated from Morocco at a young age, and knew very little about the Holocaust.

Amram Lusky: You see, I come from a community that didn’t suffer at the hands of the Nazis. Everything we knew came from the radio, or from what we heard from the rabbi in synagogue. And don’t forget, I was only a kid during the war. So when they told me, “this is the Nazi criminal Adolf Eichmann,” I didn’t even know who Adolf Eichmann was. I remember the first time I saw him as if it were yesterday. I saw this pale, scrawny guy. He was about my father’s age, and was wearing these military issued clothes the IDF had given him.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Another one of the guards, Shalom Nagar, who was born in Yemen, also couldn’t really imagine his mild and polite prisoner as a heartless monster.

Shalom Nagar: He had this presence, I thought, what a righteous man. When I would take him to the restroom I’d chain his legs. When I would take them off he’d say thank you, in Spanish, ‘gracias.’ You didn’t feel that he is cruel. He was calm, he was sitting in his corner, he had a desk, a chair, and all day long he would write. Either write or read. He had a bed next to him and if he was tired he would go to bed and sleep. That’s it.

Katie Pulverman (narration): These two men – the German SS Lieutenant Colonel and the Yemenite Jewish prison guard – didn’t really have a common language.

Shalom Nagar: I couldn’t teach him Yemeni Arabic, and he wasn’t successful in teaching me German, so he communicated with me through hand gestures.

Katie Pulverman (narration): As a result, there was little communication between Eichmann and his guards.

Amram Lusky: It was absolutely forbidden to talk to him. Here and there we would sneak in a few words, but mainly we just kept quiet.

Katie Pulverman (narration): All of this was, of course, by design. Guys like Amram and Shalom were selected to guard Eichmann precisely because they had no personal connection to the Holocaust: They wouldn’t try to engage the prisoner in conversation, or – and this was a real concern at the time – try to hurt him. In fact, Eichmann was such a high-profile prisoner and the anxiety surrounding his well-being so great, that even the guards were closely monitored.

Amram Lusky: I mean they didn’t want to take any chances. Just imagine what would have happened if in some moment of madness, a guard would have killed Eichmann. So we guarded him without a rifle, without any blunt instruments that could endanger him. They’d search us before we went into the cell. Make us to take off our belts. Just like him, really.

Katie Pulverman (narration): It didn’t take long for Amram and Shalom to learn all about the man they were charged with guarding. Reports about Eichmann appeared daily – in print, on the radio.

Amram Lusky: The more we learned about him, the more we learned about what he had done, and about how bad he was, we began hating him. I personally hated his guts. But in the cell, I always smiled at him.

Katie Pulverman (narration): When he wasn’t in his cell, Eichmann was being interrogated. Endlessly. During the first nine months of his imprisonment in Israel, he was cross examined by members of the Zero-Six Bureau – a special police unit set up for the purpose of collecting all the information needed for Eichmann’s trial. One of the fourteen Zero-Six investigators was Michael Goldman-Gilad. He’d actually left the police two years earlier, and was just getting used to civilian life when he heard Ben Gurion’s announcement on the radio.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: When Ben Gurion told in the Knesset that Eichmann is here, that we brought him from Argentine, I sent a letter to the Chief Inspector of the police that I am ready to be in the special unit which will investigate Adolf Eichmann. And he told me that it’s impossible to be only for a time. For investigation in this unit, I have to return to the police. So I return to the police.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Michael can’t forget the first time he saw the man responsible for sending his parents, sister and brother to their deaths.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: I remember exactly. When I saw him sitting in front of me for the first time, when he opened his mouth I had the feeling that I see the gates of the crematorium open. That was my first feeling.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Avner Less, a Berlin native, served as Eichmann’s chief interrogator. [German].

Katie Pulverman (narration): This is him, in a recording from those interrogation sessions. Less clocked more than two-hundred-and-seventy-five hours with Eichmann, going over questions that the whole Zero-Six team had prepared. They taped all the sessions, and took meticulous notes. For Less, this work was personal. Most of his family had been killed in the Holocaust. That’s why he was reluctant, at first, to take on the task of interrogating Eichmann. He didn’t really want to revisit the horrors of the past.

Alon Less: And in the end my mother asked him to do this work because her parents were killed in the Holocaust.

Katie Pulverman (narration): That’s Alon Less, Avner’s son, who now lives in Switzerland. He told us, over the phone, about his father, who died in 1987.

Alon Less: He was a very relaxed man, quiet and polite. He had to get everything he could out of Eichmann.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Most of the Zero-Six team had close ties to the Holocaust. Mickey Rish, for example, was added mainly because he’d been in the camps.

Mickey Rish: I didn’t know anything about Eichmann. I knew nothing. when you’re in a concentration camp, you have no radio, no newspaper – and you don’t care what is happening, you have one worry: Survive another day.

Katie Pulverman (narration): They all say Eichmann was smart and manipulative. He realized that most of his interrogators were survivors.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: In summer, because we, we were, we were not in uniform, and he saw from time to time my number on my arm, and of course he didn’t ask or didn’t say some… nothing. And some of my colleagues in this unit, they were also ex-Auschwitz prisoners, with number. But I was sure that he, in his mind, “how I had not the possibility to kill him before?”

Katie Pulverman (narration): Eichmann famously claimed that he was a mere cog in the Nazi machine. Just a bureaucrat following orders. A paper-pusher.

Mickey Rish: Eichmann said during one of his conversations with Less, “look, I know the end of me, I only want you to trust me. To me Hitler was the legislator, if he put out a law that ordered the execution of every person over the age of fifty, I – with my own hands – would have killed my parents.”

Michael Goldman-Gilad: It was his line, “I follow orders.” And no with a personal initiative.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Michael didn’t buy this line of defence.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: We knew that he is a liar.

Katie Pulverman (narration): The extensive evidence they gathered painted a wholly different picture.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: But also in the Nuremberg trial, there were some SS officers that gave testimony against him. And they told that he was a initiator. He hate Jews fanatically. We knew that he did his job with gusto.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Throughout the questioning, Less played the role of the ‘Good Cop.’ He insisted that no one raise their voice at Eichmann, and that everyone treat him with respect.

Alon Less: Eichmann thought my father was a polite Jew, and stupid. He thought he could tell him anything and he wouldn’t know, wouldn’t understand. But my dad just manipulated him that way. Really got him to say everything.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Playing along with this calm, civilized charade, Eichmann would call Michael ‘Herr Hauptmann,’

[‘Herr Hauptmann,’ in German]

Katie Pulverman (narration): German for Mister Captain, referring to his military rank.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: For me it was difficult because I had to be very strictly and official, not to ask him personal questions, etc. Only to see him as an object for what we have to do.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Less’ orders caused some tension within the Zero-Six team.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: He was the permanent investigator, he was a really gentleman. I was not so, such gentleman with Eichmann.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Michael got particularly incensed when he heard Less call Eichmann, Herr Eichmann.

[‘Herr Eichmann,’ in German]

Katie Pulverman (narration): Sir Eichmann. Michael leapt out of his seat.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: Herr it’s the highest calling. They called us dogs, fleas, lice, and other such names. And you sit in front of him, and you are questioning him, and you tell him Herr? So after I made a scene an order was issued by the head of the unit to stop calling him Herr.

Katie Pulverman (narration): At the end of the investigation, in April of 1961, everything was set for the start of Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem’s District Court. He was accused of fifteen different charges, including crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes against the Jewish people. One of the three presiding judges, Moshe Landau, read the indictment, in front of a packed courtroom. Outside, the entire country was glued to the radio.

Moshe Landau: [Hebrew] Adolf Eichmann, tagid lo lakum.

Katie Pulverman (narration): He ordered Eichmann to stand up.

Moshe Landau: [Hebrew] Ata Adolf, bno shel Adolf Karl Eichmann?

Adolf Eichmann: [German] Yavol.

Katie Pulverman (narration): “Are you Adolf,” he asked, “son of Adolf Karl Eichmann?” Yes,” Eichmann answered.

Moshe Landau: [Hebrew] Zeho Ktav HaIshum Negdech, Mi’Ta’am Ha’Yoetz Ha’Mishpati Le’Memshala.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Standing up in his famous bulletproof glass booth, with Israeli guards at his side, Eichmann listened, almost expressionless, to a simultaneous translation of the charges.

Moshe Landau: [Hebrew] Ha’Im Hevanta Et Ktav Ha’Ihum?

Adolf Eichmann: [German] Yavol.

Katie Pulverman (narration): “Did you understand the charges?” “Yes.”

Moshe Landau: [Hebrew] Ha’Im Hincha Mode, O Eincha Mode?

Katie Pulverman (narration): When Landau asked him to enter a plea, Eichmann replied: “In the spirit of the accusation, not guilty.”

Adolf Eichmann [and then Interpreter]: [First in German, then in Hebrew] Be’Roach Ha’Ha’ashama, Lo Ashem.

Katie Pulverman (narration): The judges rejected Eichmann’s defense. Fifty-six court days and one-hundred-and-twelve witnesses later – on December 15th, 1961 – Landau handed down an unprecedented sentence: In a country that had never executed a soul – Eichmann was going to be the first.

Moshe Landau: [Hebrew] Beit Mishpat Ze Dan Et Adolf Eichmann Le’Mita.

News Reel: A story that had a grim preface in the horror of Nazi concentration camps, comes to an equally grim end in Israel, as Adolf Eichmann is sentenced for his crimes against humanity. In his bullet-proof booth, Eichmann sits stoically as the charges are summed up. The judges then call on the defendant to stand as they pass their sentence. The end of a trail of blood and horror, the end of a man whose name will be written in infamy.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Some people, both in Israel and abroad, opposed Eichmann’s death sentence. One of them was Levi Eshkol, who – just a year later – became Israel’s Prime Minister. He thought it would be better if Eichmann wandered the world bearing the mark of Cain. The Jewish philosopher Martin Buber added his signature to a letter from Israeli intellectuals to President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, expressing their concern over Israel’s moral character and international image should Eichmann’s execution go through. But they were in the minority. Most Israelis heavily favored the hanging, and President Ben-Zvi rejected the idea of a pardon. May 31st, 1962, was set as the execution date. Here’s Shalom Nagar, the Yemenite guard, again.

Shalom Nagar: After the verdict was given the commander came to me, and asked “if I need you, will you be ready to push the button?” I told him “no, not to take me.” I said, “Why don’t you want to do it? Or we have Ashkenazi brothers whose families suffered, let them.”

Katie Pulverman (narration): On May 31st, Shalom was already on his way home after a long shift.

Shalom Nagar: Pitom Atzar Otto Al Yadi… [goes under].

Katie Pulverman (narration): A car pulled up next to him. It was his commander. “We’re one person short,” he said. “You need to come.”

Shalom Nagar: Nagar Bo Kanes… Ata Tzarick Lavo.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Shalom got in the car, and they drove to the Ramle Prison, where Eichmann was held. Michael Goldman-Gilad, who was appointed to be the police representative at the hanging, was waiting for them there.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: It was a Thursday night. We were together ten men, inside. We stand near to him, about one, one-and-a-half meter. There were four journalists, one of them was a German journalist. A priest, he was together with him also before because he wanted him to confess and the priest told us after what happened. He told him, “I have no time for stupidity.” Nothing. Not one word. And then the priest, who stand near to me told him so quietly, “say Jesus, say Jesus.” And no answer. And then he told, “I believe in God, and I die believing in God.” In this moment I thought to myself, “which is his God?

Shalom Nagar: I came with the commander. We wrapped the rope around his… his neck.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: He began to speak. What I remember: “Long live Germany, long live Argentine, long live Austria. I only did my orders, and bla bla bla bla.”

Shalom Nagar: By the rules his face should be covered but he didn’t want us to do it. We told him, “OK, it’s up to you if you don’t want it, but it would be a shame.” We wrapped the rope, and there was a table, the table had a button.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: The police officer said one word, “Pe’al.” In Hebrew, “do it.”

Shalom Nagar: I pushed on the button, this opened the two shutters he was standing on, and he fell.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Within a few minutes Eichmann was pronounced dead. But there was no sigh of relief in the room. Just a quiet sense of emptiness.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: I didn’t feel nothing. No revenge, it don’t exist revenge about what they did to us. I was sure that he have to receive his punishment about what he did… not more. I’m sure that only God can take revenge. It is impossible to hang him six million times.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Shalom was deeply disturbed.

Shalom Nagar: I saw his face, his white face. His eyes were opened wide from suffocation. I thought his eyes would swallow me at that moment. And his tongue dropped down to his stomach. I just saw him and I was scared, I ran away from the guys who were there. The commander told me “Nagar, come here, come here.” I told him “leave me alone, sir, I don’t feel well!” He told me, “come and finish your work.”

Katie Pulverman (narration): But when he thinks about it today, Shalom is grateful to his commander for forcing him to come back.

Shalom Nagar: The Torah says: “For I will completely erase all memory of Amalek from the face of the earth.” I got my own living Amalek.

Katie Pulverman (narration): The group carried Eichmann’s body to a special furnace, built by a Holocaust survivor whose family had been burnt in the crematoriums. Eichmann’s ashes were placed in a milk jug.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: A milk jug of two liter. I was shocked to see how little ashes is from a man, together with his clothes! Then we went to Yaffa, to the port of Jaffa with the jug in a police boat, and after six miles of Yaffa, the Chief of all prisons in Israel, together with me, we opened the jug and we put the ashes on the… on the sea.

Katie Pulverman (narration): In a way, this marked the end of the saga, which forever changed the way Israelis talked about the Holocaust. But for that small group of people who interacted with the Nazi commander, it never really ended. Mickey Rish, the Zero-Six interrogator who had survived the camps, looks back with great satisfaction.

Mickey Rish: I think it was the most difficult job in my life. And I thank God for choosing me.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Shalom Nagar, on the other hand, was initially scarred by the experience.

Shalom Nagar: Truth be told, I remained fearful for a few months, I don’t know what happened to me. I was in the paratroopers and everything, but I was afraid of him. He was in my dreams. After a few months, maybe a year, this whole mess left me. And that’s was it.

Katie Pulverman (narration): Avner Less, the chief interrogator, left Israel, in 1968. He settled down in Switzerland and continued writing about Eichmann until his death, in 1987. As he held the empty jug, and looked out at the sea on his way back into Israel’s territorial waters, Michael Goldman-Gilad’s thoughts wandered back to the day the War ended.

Michael Goldman-Gilad: I was in the military hospital when it was the eight of May. When the War was end and they came to hospital crying and singing. They came to each one with a small glass of vodka. I remember that one told me, “you know, we will go at home, to our parents, to our family.” And I told him that I have no a home, no parents, nobody. We were three children at home, a brother he was older than me, and a sister, she was ten when they killed her. Only two cousins, they survived. Of course I was very happy that the War was end, but I was not happy because I knew that I was alone. I remember that in the same moment when we put the ashes on the sea, I said a sentence of the prophet of Deborah, Ko Yovdo Kol Oyvecha Yisrael, “So will died all your enemies oh lord.” It came on the moment. I was very relieved, I very relieved. I saw the end of one of them. So, it was the sunshine, we saw the fishers, they came back from the fishing, we saw children, they went to the school. It was a new day. A calm day.

The end song is רכבת (“Train”) by Amir Lev.