These are – it goes without saying – tumultuous times here in Israel. But especially now, we believe it is important to double down on our focus on people – ordinary people, living extraordinary lives. Because at the end of the day, once we’re all done fighting, protesting and calling each other names, we will still live together. And, given that, we might as well know who we’re living with.

So during this season of Israel Story we will meet clowns at demonstrations and air force pilots in captivity; we’ll attend a tragic funeral in Beer Sheva and sit in on an incredibly awkward first date in, of all places, our own recording studio; we’ll play therapeutic rounds of Dungeons & Dragons and place mega expensive (and complicated) long distance phone calls. And we’ll also have one giant, and still secret, audio project for Israel’s 75th Independence Day.

This season we’ll cry together, laugh together and get angry together. But whatever the emotion might be, we’ll be together. And that – at least to us – feels very good.

We chose to open our season with a theme that actually isn’t grounded here. A theme that can spread its wings, fly far, far away and provide us with a zoomed out view of ourselves.

Free As A Bird has three stories that are ostensibly about birds, but are really about the heights to which the human spirit can soar, and the depths to which it can plunge.

Six years ago, we released a Hebrew episode about the idea of letting go. At the time, we interviewed Shmulik Landau, the Chief Caretaker at the Israeli Wildlife Hospital at the Safari in Ramat Gan, who kindly invited us to tag along as he released a frail common blackbird back into nature.

Shmulik texted us the day the episode came out, and told us that he liked it, that it was very moving.

Two months later, he killed himself. He was thirty-two.

Shmulik was buried in Har HaMenuchot cemetery in Jerusalem. His colleagues from the Wildlife Hospital brought a rehabilitated Eurasian sparrowhawk they had been treating and Shmulik’s mom, Rachel, released the bird back to nature at the grave site.

Six years later, we return to the cemetery with Shmulik’s older brother Eli, his sister-in-law Sarah, and his childhood friend Shmuel to recount one final and truly unusual plot twist in Shmulik’s tragic tale.

Mishy Harman (narration): Six years ago, we released a Hebrew episode about the idea of letting go.

Mishy Harman: [In Hebrew] Hey hey, I’m Mishy Harman, and welcome to another episode of Israel Story. And this time: An Exercise in Letting Go.

Mishy Harman (narration): And for the lead of that episode, we spent a day with Shmulik Landau, the Chief Caretaker at the Israeli Wildlife Hospital at the Safari in Ramat Gan.

Shmulik Landau: [In Hebrew] We are entering the ward. [Goes under].

Mishy Harman (narration): Shmulik introduced us to some of the hospital’s patients: An injured griffon vulture from the Golan, a tortoise with a shattered shell from the Arava and a gazelle that had been hit while crossing Route Six. Then – and this is why we were there – he kindly let us tag along as he released a frail common blackbird back into nature.

Shmulik Landau: [In Hebrew] So this is a blackbird. A blackbird about to be released.

Shai Satran: [In Hebrew] Cute!

Shmulik Landau: [In Hebrew] He’s very cute! Ready? [Goes under].

Mishy Harman (narration): “Ready?” he asked as he held the small bird in his hands. “How was the release?”

Shai Satran: [In Hebrew] How was the release?

Mishy Harman (narration): Our producer Shai Satran asked him.

Shmulik Landau: [In Hebrew] It was a good release.

Mishy Harman (narration): “Good,” Shmulik said, “it was a good release.” The blackbird flew a few feet away, and landed on a nearby branch. Shmulik turned around to go back inside. “We need to let go,” he said. “He’s on his own now. We can’t keep on looking after him. We did everything we could for him. We treated him, we fed him good food, he practiced flying, and now he has to go out and make it on his own. We did our part.” As we were talking the blackbird took off, and within a few seconds disappeared out of sight. A somewhat unceremonious end to this supposedly dramatic act of letting go. But that blackbird, Shmulik made sure to tell us, was lucky. Most wild animals that come his way, he said with sad eyes, will never be released back to nature. They just wouldn’t make it.

Shmulik Landau: [In Hebrew] Those who don’t have those conditions, we put to sleep.

Mishy Harman (narration): So – reluctantly – Shmulik and his colleagues put most animals they receive to sleep.

Shmulik Landau: [In Hebrew] We understand that that’s the best outcome for them. Unfortunately.

Mishy Harman (narration): “We understand,” he said, “that that’s just what’s best for them. Unfortunately.” We gently asked whether that was also a form of letting go. But Shmulik? He didn’t see it that way.

Shmulik Landau: [In Hebrew] I wouldn’t call it a release. Let’s say that it leaves you with a heavy heart more than a light feeling of release.

Mishy Harman (narration): “I wouldn’t call it a release,” he said. “It leaves you with more of a heavy heart, a stone in your heart really, than a feeling of having let go.” Shai pressed him on this.

Shai Satran: [In Hebrew] Maybe it’s not a release into nature, but it’s a release from suffering.

Shmulik Landau: [In Hebrew] Right… [goes under].

Mishy Harman (narration): “Maybe it’s not a release into nature,” he suggested, “but you are releasing the animal from its pain.” Shmulik agreed with that, and then told us something we later realized we had only partially understood. “Sometimes you see a creature that’s scared to death, suffering physically in a way we can’t even imagine, that has been through trauma, and you feel like, ‘OK, let it be, he’ll be better off that way. That we humans have inflicted enough pain, caused enough damage, and now all we have left to do is minimize its suffering. It doesn’t feel like a release to me, but you can call it that if you want to.”

Adina Karpuj tells a story of three best friends – Amir Balaban and brothers Yoav and Gidon Perlman – who, for the last forty years, have been united by their joint love of birds.

In 2015, when 43-year-old Gidon – a leading cardiologist – was diagnosed with ALS, he decided it wasn’t going to slow him down. After all, he still had many birds he wanted to see. And thus started an adventurous journey – equal parts satisfying and irresponsible – to “get” Gidon his birds.

In a tale that begins with a stolen falcon chick and ends with a modern-day version of the miracle of Jesus walking on water, we encounter – up close – the sheer power of human resilience.

Adina Karpuj (narration): On the morning before Passover, I left my Jerusalem apartment and headed down Gaza Street. Evidence of pre-holiday cleaning – open packages of pasta, half-consumed loaves of bread, and tins of microwavable Quaker oats – were strewn along the sidewalk. It was still quiet outside, and save for a honk here or there, it was just me and the birds.

Adina Karpuj: Ooh, listen to that one. I think it’s going to be a good day. Good day for birding.

Adina Karpuj (narration): I was on my way to the Jerusalem Bird Observatory, which is right across the road from the Knesset’s Rose Garden. And when I arrived – just before 7am – the day’s activities were already in full swing.

Amir Balaban: [In Hebrew] Good. Stretch out your hand, put it out like that. Good. [goes under].

Adina Karpuj (narration): Teenagers in cargo pants and hiking boots were entering data points into a computer. A gaggle of little girls crowded around a tall, bald man with a tiny bird in his hand. But I wasn’t there to learn about migratory patterns or mating calls. Instead, I’d come to hear a story about the three friends who run this place: The bald guy, Amir.

Amir Balaban: My name’s Amir Balaban. I’m the head of the Urban Wildlife Initiative in the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Yoav…

Yoav Perlman: OK, so my name is Yoav Perlman. I’m a birder. Currently I’m the director of ‘Birdlife Israel,’ which is a branch of the Society for Protection of Nature in Israel.

Adina Karpuj (narration): And his older brother, Gidon.

Gidon Perlman: [Three clicks] I am Gidon Perlman.

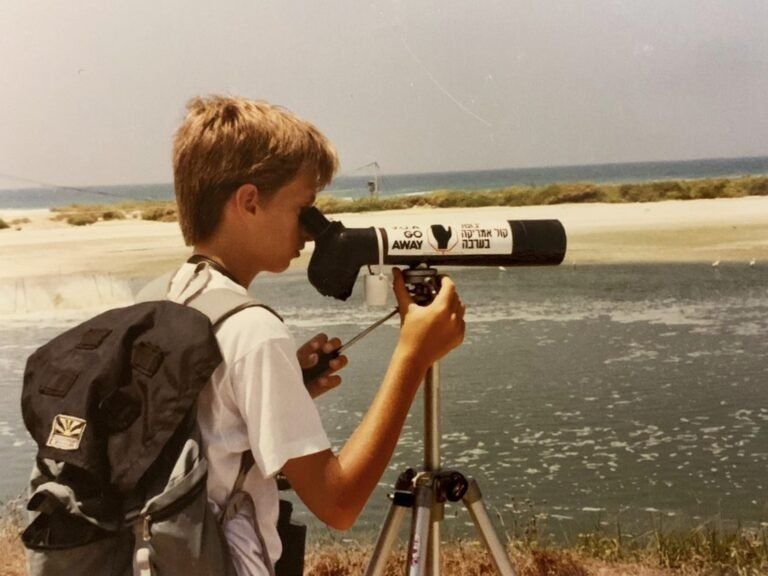

Adina Karpuj (narration): Their story begins back in 1975. Eleven-year-old Amir was bored, restless and feeling adventurous. A dangerous trifecta if there ever was one.

Amir Balaban: In those days, it was either soccer, crack, chess, or birding.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Yeah, birding. This new ornithological addition to the after-school landscape of mid-seventies Jerusalem was the passion project of a young zoology grad student.

Yosssi Leshem: OK, my name is Yossi Leshem. Some people say that I am a craziest guy because I am always doing what I want to do, but I think this is my advantage.

Adina Karpuj (narration): And what he wanted to do was make the boys and girls of Jerusalem fall in love with birds. So he opened the city’s first, and only, birding club.

Yosssi Leshem: You have always to think out of the box.

Adina Karpuj (narration): The club attracted a bunch of nature nerds, who’d follow Yossi into the woods armed with binoculars. It was a small-scale operation. Then, one day, Yossi got an unusual call. The man on the other end of the line told him that…

Yosssi Leshem: There is a young boy that is raising a falcon at his home.

Adina Karpuj (narration): A young boy raising a falcon – a wild bird of prey – in his bedroom. And that young boy? None other than our rambunctious sixth-grader – Amir.

Amir Balaban: I was always a troublemaker in school, so together with a few friend we robbed a nest.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Now, it was (and still is) illegal to capture and raise falcons. But none of that seemed to matter to Amir and his friends. They divided the chicks between them and thought they had gotten away with it.

Amir Balaban: But it wasn’t the perfect crime because the flat owner knew me.

Adina Karpuj (narration): A neighbor noticed what was going on and decided to teach the boys a lesson.

Amir Balaban: So he called the SPNI.

Adina Karpuj (narration): That’s the Society for Protection of Nature in Israel.

Amir Balaban: And they told him, “talk to Yossi Leshem.”

Adina Karpuj (narration): The guy phoned Yossi, the zoology grad student, recounted the story, and asked for help. Yossi, totally outraged, called up Amir and demanded that he release the poor falcon chick at once. But Amir – quite the daredevil – promptly refused. Yossi had no other recourse than to call the cops.

Yossi Leshem: I told the police, “come and confiscate it because it’s against the law.”

Adina Karpuj (narration): The cops summoned Amir to the station.

Amir Balaban: And I was fingerprinted as an eleven-year-old, that’s quite an experience.

Adina Karpuj (narration): As for his punishment…

Yossi Leshem: I told the policeman, “listen, you know, he’s a young guy, he’s not… he doesn’t understand what he’s doing exactly. Tell him that if he releases the falcon, then the only thing will be that he can join the bird club, and he will see that we have to protect the bird and not put him in a cage or hold them at your home.”

Adina Karpuj (narration): With the alternative being criminal charges, Amir reluctantly joined Yossi’s birding club. And, to his surprise…

Amir Balaban: What happened was that I turned from a hunter into a conservationist.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Amir liked it so much that he stayed on, long after his unofficial punishment time was up. He soon became Yossi’s protégé and even started guiding younger kids as a birding counselor. It was then, in the early 80s, that two scrawny – and enthusiastic – brothers showed up: eleven-year-old Gidon and eight-year-old Yoav.

Amir Balaban: Suddenly you get these two thin, blond kids holding a pair of binoculars in one hand and a sandwich on the other hand. I would stop for lunch and they will not. And when you see people that won’t give up birding time when they’re hungry, you understand that you have suckers on your hand and that they’re there for the long ride.

Adina Karpuj (narration): And so it was. Apparently uninterested in crack, chess or soccer, the Perlman brothers became regulars at the birding club. Here’s Yoav, the younger of the two.

Yoav Perlman: I must admit that in the first years, Gidon… I think he looked at me as the annoying young brother and he didn’t really want me to join the group. But I think he understood that I’m not giving up from quite a young age, we spent a lot of time together birding and trained together.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Amir taught them how to ring – a monitoring method which involves trapping birds in nets, taking their measurements, and placing a metal ring with a serial number on one of their legs before releasing them back into the wild. Yoav remembers how they’d travel all over the country to set up their gear before dawn.

Yoav Perlman: Birds are active early in the morning usually. Sometimes you wake up at three or four, drive somewhere, set up the nets, the gear, and start work at first light.

Adina Karpuj (narration): At 18, Amir was, supposedly, the responsible adult. But, once a daredevil, I guess, always a daredevil. And in the brothers he found eager young partners.

Yoav Perlman: Together we do many stupid things, take too many risks, too many adventures.

Adina Karpuj (narration): One time, for instance, Amir convinced them to…

Amir Balaban: Cross the Israeli-Syrian-Lebanese border on Mt. Hermon because all the good birds are beyond the border. So you have to pass all the army checkposts as a stow away in uh… in an army truck. And then you could walk wherever you like – into Syria or into Lebanon depending on the birds. And this is how we added some very nice birds to our list. It was very irresponsible, but yet very satisfying.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Irresponsible yet satisfying. That would become a motto by which all three of them would go on to live.

Yoav Perlman: Because Amir was my mentor in those early days I think I grew up as an irresponsible and reckless adult. [Amir laughs].

Adina Karpuj (narration): In 1984, Amir – the beloved counselor – was drafted into the army. He joined a special-ops intelligence unit and – after his compulsory service- signed on as an officer. When it was time for Gidon, his former birding mentee, to enlist, Amir secured him a spot-in the very same unit. Yoav, the younger brother, was still in high school, but they’d all meet up on weekends, to bird of course. This went on for years. Sometimes, they’d travel hundreds of kilometers at a moment’s notice to spot a rare bird. Other times, they’d head out to their backyards – apparently they saw more than one-hundred and sixty species just outside their living rooms. Surprisingly though, the place they frequented most was the Knesset. Or well, right outside of it. During one of those visits, on a clear Saturday morning in April 1994, they were setting up their ringing nets near the Rose Garden, just as they’d been doing for years.

Amir Balaban: It was a beautiful spring morning. First round. Net number one. And I saw this little bird, and it had a ring. And I said, “wow, we haven’t ringed here for at least two weeks. I wonder if it stayed two weeks.”

Adina Karpuj (narration): It was a lesser whitethroat – a small warbler with a gray back and white underbelly.

Amir Balaban: And I remember reaching for the bird, taking it out, looking at the ring and just freezing.

Adina Karpuj (narration): To their amazement, this wasn’t a bird they’d ringed two weeks earlier, or, for that matter, ever. The bird had been ringed thirty-three-hundred kilometers away in Sundre, Sweden. And for all you non-birders out there, Amir explains that catching a bird with a foreign ring is rare. Very rare.

Amir Balaban: I don’t know if you believe in omens, but it was like an omen.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Come spring, birds like this lesser whitethroat would voyage from their Saharan winter to a cool Scandinavian summer. Jerusalem was a mid-journey pit-stop. Amir, Gidon and Yoav, you see, were standing in the middle of one of the world’s busiest intercontinental avian highways. Clearly, they thought to themselves, this was the place to set up a toll booth. And that’s how the Jerusalem Bird Observatory, or JBO, was born.

Amir Balaban: That was the start of the path.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Somehow, the three passionate friends managed to convince the state to hand over an…

Amir Balaban: Acre-and-a-half of prime real estate between the Parliament and the Supreme Court.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Yeah, imagine the US federal government giving three amateurs in their twenties a plot of land on the National Mall. But that’s exactly what happened, and almost immediately the trio assembled a team, built an artificial pond, planted trees and constructed a bird hide. They transformed a dilapidated storage room in the Knesset’s backyard into the offices where – almost thirty years later – I would meet them on that pre-passover visit.

Amir Balaban: Instead of a derelict asbestos hut, we converted it into a research station and educational facility. We’re sitting actually where the tractor and all the herbicides were kept.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Today, Amir told me…

Amir Balaban: We have about 50,000 paying visitors for guiding services every year, and I would say about another 50,000 or even more that just pass through in the afternoons, Shabbat, you know.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Amir, Yoav and Gidon spent a lot of time and energy making their JBO dream a reality. And they assumed this is how things would always be, researching at the observatory and birding out in the field – sandwiches in one hand, binoculars in the other. But a few years in, Gidon – the older of the two brothers – threw a wrench into those plans.

Amir Balaban: I remember we guided a young ornithological trip to Eilat. And on the way back he, like, told me, “listen, I decided to go and study medicine.” And I told him, “are you crazy?! You can’t do it, you know? It’s too demanding, you know? What about our project?” And I didn’t stop badgering him until we got to Jerusalem. It’s two-and-a-half hours and he didn’t budge an inch!

Adina Karpuj (narration): Despite Amir’s pleas, Gidon enrolled in medical school.

Amir Balaban: And he proved me wrong.

Adina Karpuj (narration): But even so, Amir never stopped complaining.

Amir Balaban: When he became a doctor, that also – I said “listen, you’re saving people. It’s… It’s not ecological to save people, you know? Nature has to do its course. You have to let them die. You know, you’re working against us.” No, he has to save people.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Gidon promised Yoav and Amir that he wouldn’t give up birding. And he kept that promise. Between rotations and shifts at the hospital he’d join them out in the field to ring.

Amir Balaban: Gidon can do eight things at once. But that’s Gidon. He’s one of a kind.

Adina Karpuj (narration): As they each advanced in their respective careers – Yoav and Amir in wildlife conservation, Gidon in medicine – birding always remained the glue. They each got married and had kids. But at heart they were still just three pals, on a neverending birding odyssey. Life was good. Stable. Yoav worked at the SPNI, Amir headed the observatory, and Gidon climbed the ranks of the medical world. In March 2015, he was offered a prestigious fellowship in cardiology at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, Canada. He was at the top of his game, doing research, operating, and, in his free time – it goes without saying – birding. But then…

Gidon Perlman: [In Hebrew] I started to feel weak.

Adina Karpuj (narration): That’s Gidon.

Gidon Perlman: [In Hebrew] I am Yoav’s brother.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Gidon started feeling a sharp pain in his right leg, and when it wouldn’t go away, he – begrudgingly – got it checked out. After all, he was in Vancouver to be the doctor, not the patient. But after weeks of tests and medical exams, the verdict came back: ALS.

Yoav Perlman: I remember the moment. It was a late night call, and I understood that something is going on.

Adina Karpuj (narration): That’s Yoav, who received the news from their father.

Yoav Perlman: Yeah, it was quite a… quite a shock, especially because Gidon was so active, and so excellent, and so young back then.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Gidon was 43 at the time, 12 years younger than the average age of ALS diagnoses. He was given three years to live. It’s now been seven. Gidon can no longer speak. At least, not with his mouth. To communicate anything more than a grunt, he uses an iPad, staring at each character on the keyboard long enough for it to recognize his gaze. Every letter, let alone word, takes significant effort. And his articulation is extremely slow. Not because his mind is sluggish, but rather because the technology attempting to replace his mouth simply isn’t there yet. Those clicks you hear between each of his words are the sound of him “typing,” with his eyes that is. I’ve condensed them here for the sake of time, but you should know that a simple sentence – “I’m Yoav’s brother,” for instance – can take a full minute or more. And that hum you hear in the background? Those are the various machines that allow him to breathe and cough. Or, in other words, keep him alive. Amir and Yoav told me that many ALS patients choose a certain “red line,” beyond which they aren’t willing to go on with their treatment. For some it’s the feeding tube, for others it’s intubation once breathing independently becomes impossible. But Gidon took a different approach. Almost immediately after the diagnosis he decided that ALS wasn’t going to stop him: He had children to raise, research to do and – of course – birds to spot.

Gidon Perlman: [In Hebrew] I want to see as much as possible.

Adina Karpuj (narration): ALS or not, he was determined to criss-cross the globe, and track down as many birds and other rare species as possible.

Yoav Perlman: We actually decided that we’re going on this big cat quest.

Adina Karpuj (narration): A big-cat quest. Why? Because, as Yoav claims…

Yoav Perlman: Big cats are something special, they’re like honorary birds.

Adina Karpuj (narration): “Honorary birds” – something only true ornithologists would ever say.

Amir Balaban: The idea is making lemonade from lemons.

Adina Karpuj (narration): That’s Amir once again.

Amir Balaban: Gidon’s the best excuse to travel all over the world. You know, Gidon needs to see a tiger. You know, he has ALS and he’s never seen a tiger. He missed it in his twenties, so we have to get him a tiger.

Adina Karpuj (narration): So the trio sprung into action, adding in a fourth musketeer – their childhood friend, Eli.

Eli Karniel: My name is Eli Karniel.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Eli is – conveniently – a physician. And thus, team roles were assigned.

Amir Balaban: Yoav is well connected. Eli’s a doctor. I’m in charge of fun and games.

Gidon Perlman: [In Hebrew] We were a special team.

Amir Balaban: And the adventures are crazy, of course.

Adina Karpuj (narration): They saw black bears and humpback whales in Canada, went dog-sledding in Alaska, spotted a Pallas’s Fish-Eagle in an Indian sewage dump, and laid eyes on an Iberian lynx in Spain. As you can imagine, the habitats in which these animals live aren’t exactly gold-standard accessible. But that wasn’t going to stop them.

Yoav Perlman: The logistics of traveling with a person with disabilities are quite complicated. Gidon’s physical condition did deteriorate between trip and trip. Emmm, Gidon started saying something.

Gidon Perlman: [In Hebrew] I wasn’t scared. That’s life.

Adina Karpuj (narration): And, just in case anything went wrong, there was Eli.

Eli Karniel: I was equipped like an intensive care unit. Had everything on my back.

Amir Balaban: Eli is the most, I’d say, professional irresponsible doctor I know [laughs], and we need him on board.

Adina Karpuj (narration): On one of these expeditions they found themselves in the world’s largest tropical wetlands.

Yoav Perlman: The Pantanal in Brazil, that’s the place in the world to see jaguar. And everything was great, we had fantastic time.

Adina Karpuj (narration): In fact, Amir recalls, they were having so much fun that they simply couldn’t leave.

Amir Balaban: One of our main problems is knowing when enough is enough.

Adina Karpuj (narration): When they were finally heading out of the wetlands and back to their hotel, they suddenly saw…

Yoav Perlman: This big sign “do you want to see Agami Heron?” Agami Heron is like a most beautiful and rare heron.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Spontaneous detours with a paraplegic ALS patient in a remote Brazilian river? For these guys, a no brainer. There was just one small problem.

Yoav Perlman: There are caiman alligators there in the in the water and piranha fish in that river.

Adina Karpuj (narration): But the opportunity to see such a rare bird was just too tempting.

Yoav Perlman: And we thought, “yeah, why not? Let’s try.”

Adina Karpuj (narration): So they did.

Yoav Perlman: It was a three meter climb down from the pier. Tiny, very unsafe boat.

Eli Karniel: Very, very, very narrow.

Yoav Perlman: And we thought ‘nah, it’s too dangerous, it’s too unsafe.’

Adina Karpuj (narration): They were, Yoav remembers, about to fold.

Yoav Perlman: But Gidon really insisted and we agreed on, on, on doing it. So we put Gidon on a, like a white plastic chair and a few of us, we sort of lowered him down the ladder into that tiny boat.

Eli Karniel: We kind of improvised because it was too low for him to sit on the regular bench.

Adina Karpuj (narration): With Gidon settled in, the team started canoeing around the river, looking everywhere for the Agamis.

Yoav Perlman: We didn’t see the heron. It was a bit too late in the day, but it was a nice trip nevertheless. And when we got back to the pier, Eli – who’s uh, quite a big guy – he stood up because he wanted to climb up the ladder and start arranging things to get Gidon back on shore.

Amir Balaban: He just rose from his chair, and… the boat started swaying.

Eli Karniel: I rocked the boat.

Adina Karpuj (narration): To everyone’s horror, Gidon went flying in the air.

Eli Karniel: I see him, mid-air, falling into the water. Boom.

Yoav Perlman: Plomp.

Eli Karniel: Flew off.

Yoav Perlman: Fell into the water.

Amir Balaban: You know, you couldn’t say Jack Robinson, Gidon was head first into the murky, brown water of this caiman- and piranha-infested river.

Yoav Perlman: Instantly he went down three, four meters.

Amir Balaban: And he just disappeared.

Eli Karniel: He can’t help it.

Amir Balaban: You have the dilemma, ‘is this over, or… or not?’ And I just remember seeing Noga’s face…

Adina Karpuj (narration): Noga is Gidon’s wife.

Amir Balaban: In front of my face when I come back to Israel and I tell her that Gidon drowned in a river in Brazil. And without having a second thought I jumped in.

Yoav Perlman: Amir and Eli – instantly they jumped after him.

Eli Karniel: I had my passport on me and my phone and everything.

Yoav Perlman: It was quite scary, but they managed to get him out.

Eli Karniel: We took him to the… the shore.

Adina Karpuj (narration): All’s well that ends well? Not quite. Here’s Amir.

Amir Balaban: My binoculars, my beloved Swarovski binoculars, fell into the deep abyss. And then I had a second dilemma – whether to jump in and search for the binoculars.

Yoav Perlman: So Amir and I went back into the water and we started diving to search in the mud there in the muck in the mud.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Again and again they came up empty-handed.

Yoav Perlman: So one of us was diving and another one was with a metal rod, ready to hit the caiman when it comes close. Eventually we found the binoculars and Amir was sort of floating on his back. And then I see the caimans starting to swim to him and I tell him, “Amir, I think it’s time you get out of the water. There’s a caiman.”

Amir Balaban: And suddenly I hear them shouting, “get out of the water! Get out…” [laughs].

Yoav Perlman: And he said, “nah, you must be kidding.”

Eli Karniel: “Oh come on guys. Stop that shit.” You know, just like, “pulling my leg.” I said, “no no, look back, he’s swimming at you. Get the fuck out.”

Amit Balaban: And I look towards my feet and I see this caiman starting to swim towards me. I think this was my fastest swim ever back to shore and they were laughing their heads off [laughs].

Yoav Perlman: It was quite, quite scary.

Amir Balaban: But uh, it ended well.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Even though Gidon soon lost the ability to breathe independently and impulsively hopping on a canoe in a river flush with piranhas seemed like a lifetime ago, the crew just kept on going, adding more and more exotic animals to their bucket list.

Yoav Perlman: Tiger, lions and cheetah and leopards.

Gidon Perlman: [In Hebrew] Wild dogs and wolves.

Adina Karpuj (narration): When flying abroad became impossible for Gidon, they shifted to local adventures.

Yoav Perlman: Yeah so in July we went to the Kinneret.

Amir Balaban: We created a pyramid of rafting boats that could sustain the weight of four adults and a hundred-and-twenty kilo wheelchair. I think since the miracle of Jesus walking on water, never has the Sea of Galilee seen a crazy sight such as this.

[Tape from the Kinneret outing]

Adina Karpuj (narration): This is audio from a video taken at that outing. Amir’s pointing out purple heron to Gidon, who’s sitting underneath a beach umbrella, being fed fresh watermelon and seemingly enjoying the adventure more than anyone.

Yoav Perlman: And that’s how it works. Gidon says, “take me there,” and we – like good soldiers – we get everything together and do it.

Amir Balaban: A theme in whatever we do is that if you get a bad card, do something good with it.

Gidon Perlman: [In Hebrew] Agreed.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Gidon’s condition has declined quite a bit since I began interviewing him. It’s become harder and harder for him to answer questions or even reply to texts. He’s extremely tired and doesn’t get out as much as he used to. On one of my visits to the JBO – this time without Gidon – I met his ten-year-old daughter, Naama. I couldn’t help but notice the white bengal tiger on her t-shirt. She’s her father’s daughter, that’s for sure. Naama was gently detangling a bird from a net, trying to beat her own record for most birds ringed in a single day.

Naama Perlman: Wait, that was the sixth one!

Adina Karpuj: Yay!

Naama Perlman: Yes…

Adina Karpuj (narration): I asked her what she likes so much about coming here.

Naama Perlman: Taking the birds out of the net, holding them, just looking at them because they are really pretty.

Adina Karpuj: Emm hmm.

Naama Perlman: And there’s a lot to learn from them. Many things you can learn from birds, yeah.

Adina Karpuj (narration): She even had a PSA for you, dear listeners.

Naama Perlman: If, for some reason, you wake up really early, like at five, and you want to do something and you have nothing on your schedule, it will be open here.

Adina Karpuj: Really?

Naama Perlman: Yeah, at five they open…

Adina Karpuj (narration): Unsurprisingly, Naama wants to be an ornithologist when she grows up, and though she’s still too young to officially join the club, she trains on her own.

Naama Perlman: Yup, I already started doing it.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Or, sort of on her own. See, Yoav and Amir have stepped in where her own dad no longer can, and will often pick Naama up at the crack of dawn so that she can help them ring. In fact, adventures at unusual hours are something that happen with a certain degree of regularity. A few months after I first met the crew, I got a text message from Yoav. “Feeling spontaneous?” he asked. “Sure,” I texted back. “Good, later tonight we’re heading into the desert. Gidon wants to see a certain kind of rare fox. You in?”

Adina Karpuj: [In Hebrew] Hey! OK. How you doing?

Yoav Perlman: [In Hebrew] OK.

Adina Karpuj (narration): When I arrived at our meeting point, Gidon wasn’t there. He had hired a special taxi to traverse the mountains and valleys, dry riverbeds and gravel roads leading to the spot of the stakeout. By the time Amir, Yoav and I got there, he was already situated…

Adina Karpuj: [In Hebrew] Hey Gidon, how are you? [goes under].

Adina Karpuj (narration): Looking up at the starry night, waiting for the fox.

[Gidon Perlman grunts]

Adina Karpuj (narration): Gidon’s iPad struggles to calibrate outdoors, which rendered him non-verbal for the evening. When he needed something, a game of ‘20 Questions’ began.

[Gidon Perlman grunts]

Yoav Perlman: [In Hebrew] I can’t understand you. Amir, can you understand him? Come listen a second.

Amir Balaban: [In Hebrew] Say it again, Gida’le.

[Gidon Perlman grunts]

Amir Balaban: Glasses? No.

Adina Karpuj (narration): “Is it your glasses?” Amir asked. Gidon shook his head, “no.”

Amir Balaban: [In Hebrew] Are you cold? Are you hot? Is it your hand? Your legs? The angle of your wheelchair?

Yoav Perlman: [In Hebrew] Do you want to sit up more? Or lie on your side?

Adina Karpuj (narration): Are you cold? Are you hot? Is it your hand? Your legs? The angle of your wheelchair? Do you want to sit up more? Or lie on your side? This went on for a while and no one was ever able to figure out what exactly Gidon actually needed. Because in the middle of all the guessing, the fox suddenly appeared.

Yoav Perlman: [In Hebrew] It’s here. It’s here. There, there, Gidon.

Adina Karpuj (narration): Yoav asked his brother if he managed to see it. A huge smile spread across Gidon’s face. Yes, he had. A few days later, back in Jerusalem, I asked Amir if they ever think about slowing down for the sake of Gidon’s safety. He seemed amused by my question.

Amir Balnaban: [Laughs] Wha… What’s the worst that can happen, that he’ll die? He was expected to have three years. He’s now running into seven. Gidon’s never going to give up easy.

Adina Karpuj: And do you think about the day after?

Amir Balaban: Yeah, like everybody else. You know, my day after, your day after. All of us are going to have a day after. So I’m not much, you know, worried about it or giving it much attention. It will come. It will have its bad side, it will have its good sides.

Adina Karpuj (narration): When Amir said that – that Gidon’s death will have its good sides – I assumed he was referring to the sense of relief that can often accompany the end of a loved one’s battle with a long and debilitating disease. That feeling that they’re now at peace, that the suffering is over. But Amir… what can I say? He’s a naturalist, through and through.

Amir Balaban: Remember, at the end of the day, every person alive is bad for conservation. We need to die. We need to make room. Our body has to decompose. We need to release the energy we’re taking for something else, in order to create life. It’s a cycle of life. So if you get a long ride, it’s not always good. If you get a short and happy ride, that’s the best. The mentality in what were trying to achieve as long as Gidon is with us is carry on, doing what we like. Full steam ahead.

Adina Karpuj (narration): The next time I saw Gidon, I asked him what was next. What he still has left to do. Yoav took a moment to wipe the saliva that had run down his older brother’s chin so that he could answer me more comfortably. Gidon looked at me, then he looked at his brother, smiled mischievously and started to type.

Gidon Perlman: [In Hebrew] To live and create. I am writing a book… [Goes under].

Adina Karpuj (narration): He’s currently writing a book about the Jerusalem Bird Observatory, and still works in the medical field, too. He continues his research at Hadassah Hospital and is developing cardiovascular stents at a company called Medinol. Just recently, they released a new coronary stent, the PERL, named for its lead scientist, Gidon Perlman. Unfortunately, the pandemic put a huge wrench in the big cat quest. And for fear of infection, Gidon moved to working entirely remotely. For good. The one place he still frequents, though less and less these days, is the observatory. On my last visit there, I found him sitting in his fancy electric wheelchair, looking up at a large computer screen. Two young ornithologists next to him were entering observation data into the system, while Amir was teaching a group of kids how to release ringed birds back into the wild.

[Gidon Perlman grunts]

Amir Balaban: [In Hebrew] Six? Five? It’s five-years-old.

Adina Karpuj (narration): It’s a little hard to hear, but Gidon would occasionally let out these low-pitched grunts, indicating to the teens that they’d made a mistake. Amir – his interpreter – would stop whatever he was doing to explain to them what Gidon meant. Meanwhile, Yoav was ringing on his own nearby. Things were, in some strange way – and give or take an oxygen tank and feeding tube – just as they’d always been. The trio, together, doing what they love.

Little girls: Woah!

Back in the 1980s and 1990s you couldn’t turn on the radio or switch on the TV in Israel without encountering Doron Nesher. He was everywhere, and everything: a singer, an actor, a poet, a broadcaster, a comedian, a popular TV host.

He was good-looking, eloquent, smart.

Today, following a nearly fatal stroke he suffered a decade ago, 68-year-old Doron is a different man. He is a man on a journey of rebuilding and refinding himself. He is trying to discover who, and what, makes up the person he now is.

Actors Yishai Golan and Gilia Shtern Nechmad read a story Doron wrote about a bird – a hoopoe bird to be precise – that served as the long-lost key to a seemingly impenetrable lock.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): We released the Hebrew episode that included our visit with Shmulik – the Chief Caretaker at the Israeli Wildlife Hospital whom we met at the top of the hour – in January 2017. Shmulik texted us the day it came out, and told us that he liked it, that it was very moving. Two months later, Shmulik Landau killed himself. He was thirty-two. When we relistened to what he had told us about injured animals, that sometimes he received creatures who were suffering so terribly, that he felt, ‘OK, let it be,’ let’s end their pain,’ we suddenly understood he may have been talking about himself.

Eli Landau: [In Hebrew] When I listen to what you asked him then, I shiver. Because without knowing it, you were asking him about himself.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Shmulik’s older brother, Eli.

Eli Landau: [In Hebrew] That was exactly the dilemma he lived with all the time – whether to give up or to continue to fight. For many many years Shmuel tried to live. And for many many years he tried to die.

Mishy Harman (narration): The successful attempt which ended Shmulik’s life hadn’t been his first. For years he struggled with eating disorders, and sadness, and – though it was never officially diagnosed – a borderline personality disorder. He was the youngest of six children in a very religious family (today we’d call them chardalim, or nationalist charadim). He grew up in Kiryat Moshe, a religious neighborhood at the entrance to Jerusalem. Shmulik and Eli’s dad had made aliyah from the States, but left that life behind, which is why, Eli, apologized.

Eli Landau: My English is not so good, but I can try.

Mishy Harman (narration): Instead of going to the army, Shmulik volunteered at the Safari, as part of his national service. And then he just stayed there, for almost 15 years, till the very end.

Eli Landau: And you know, he… he keep a normal face and normal life outside. And…

Sarah Landau: It was his way to survive.

Eli Landau: I think so, yeah.

Sarah Landau: To be meaningful, to be for animals and people as well.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Sarah, Eli’s wife, Shmulik’s sister-in-law.

Eli Landau: [In Hebrew] Look, he tried to kill himself many times. And to get up, after a suicide attempt and try to go on with your normal life? That’s something you can only do if you can make a complete separation between things. You can’t do it any other way. It’s just too painful. And that’s the pain that he ultimately ended. I can understand that, but we’re the ones left behind. We’re the ones with that stone in our heart.

Mishy Harman (narration): Shmulik was buried in a wall – that’s the new burial method here in Israel, since cemeteries are running out of space. His colleagues from the Wildlife Hospital brought a rehabilitated Eurasian sparrowhawk they had been treating and Shmulik and Eli’s mom, Rachel, released the bird back to nature at the gravesite. There’s an amazing photo of the moment of the release, which you can see on our website, israelstory.org. We’ll return to Shmulik – and to one final and truly unusual plot twist – at the end of the episode. But for now, let’s continue with a completely different tale, in which a bird – a hoopoe bird to be precise – served as the long-lost key to a seemingly impenetrable lock.

Doron Nesher: Look, I… I… I can’t. I can’t.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Doron Nesher. Back in the 80s and 90s you basically couldn’t turn on the radio or open the TV in Israel without encountering him. He was everywhere. And everything: a singer, an actor, a poet, a broadcaster, a comedian, a popular TV host. His 1987 film, Blues La’Chofesh Ha’Gadol, or Late Summer Blues, opened the Jerusalem Film Festival, became a cult film overnight and is – till this day – one of the most popular and iconic Israeli films of all time. He was good-looking, eloquent, smart. And then, at the height of his success and fame, he decided to leave the spotlight, and move to the States, where he served as a JNF emissary for ten years. Given that, you might have thought that doing this interview in English would have been a piece of cake for him. But…

Doron Nesher: I forgot my English and it isn’t that I just “forgot” it. As part of my stroke, my English was entirely erased. You can’t imagine what it’s like. I mean, for ten years I was in America, living in San Francisco, and I used to perform in English. Can you imagine? Now I have to learn the language from scratch.

Mishy Harman (narration): So our conversation, in Doron’s home in Ramat HaSharon, took place entirely in Hebrew. Doron’s 68 now, and has – since he suffered a nearly fatal stroke in August 2012 – been on a journey. One in which he’s rebuilding himself. Refinding himself. Discovering who, and what, makes up Doron Nesher.

Doron Nesher: And I still don’t know who I am. I am learning everything from the start.

Mishy Harman (narration): The stroke, he says, was the defining moment of his life.

Doron Nesher: It’s like an earthquake that devastates everything. Everything. Everything. And now my right leg and right arm are paralyzed. But my greatest difficulty is my aphasia.

Mishy Harman (narration): Aphasia can refer to many different things, but in Doron’s case it’s an inability to formulate language. To retrieve certain words.

Doron Nesher: If I want to say a simple sentence, I can. Things like, “I want to eat,” “I’m tired,” or “I’m hungry.” All that’s OK. But if I want to say a more complex sentence, like the ones I’m using now, it’s hard. It requires endless concentration. And if, for example, I want to use a word I haven’t said in a while…

Mishy Harman: You have to somehow bring it up from the depths.

Doron Nesher: Exactly!

Mishy Harman (narration): After his stroke, Doron spent months at Beit Loewenstein, a rehabilitation center in Raanana.

Doron Nesher: For the first three months, I didn’t say a word. And look, I understood everything. And I was trying to talk, but I just couldn’t. I kept on asking myself, how the hell do you talk? I tried, I really tried, but nothing came out.

Mishy Harman (narration): Doron worked – intensely – with a speech therapist named Tze’ela. And with her help, words slowly slowly started coming back to him.

Doron Nesher: Ta-ble, cur-tain, air-plane. Every time I managed to add another word to my collection, I was in tears. At the end of the sessions with Tze’ela I’d take the elevator back up to the ward and I’d say to people there, “cur-tain,” and I’d cry. “Cur-tain.” And they’d look at me as if I’d lost my mind.

Mishy Harman (narration): Each word was a bridge to new words. And to new parts of his old self. Getting there, arriving at each new word, forced him to dig deep into his past and into his subconscious world of associations. But certain words just wouldn’t come.

Doron Nesher: And that brings us to the story we’re here to discuss.

Mishy Harman (narration): So here are actors Yishai Golan and Gilia Shtern Nechmad reading a story Doron wrote about one of his first major breakthroughs.

Doron Nesher: Tze’ela sits at the end of a very long corridor. And there, she guards the Hebrew language as if it were a treasure. Sometimes Tze’ela reminds me of a sentry at the gate. Other times she’s a friend. Like now for instance.

Tze’ela: Hi Doron, it’s good to see you again.

Doron Nesher: We have just under an hour together. She smiles as I enter, and hands me an empty notebook with lines. I’m 59 years old and I’m learning how to write with my left hand, but also with my paralyzed right hand. I’m also relearning to talk. I don’t know how to talk anymore. I mean I do, but have issues with recalling specific words. I just can’t find them. They are right there, on the tip of my tongue, but I can’t get them out. When Tze’ela asks me to say something.

Tze’ela: Say something, Doron.

Doron Nesher: I don’t know which muscles to move.

Tze’ela: Anything.

Doron Nesher: Up until a few weeks ago I could talk freely. I even made a living talking. I could find every single word I wanted, and didn’t even have to try very hard. They were just there. Always. I don’t exactly know how to explain what happened to me. “A stroke,” they say. The connection between thought and speech has been severed. It’s tiring. Very tiring. Tze’ela shows me pictures – a chair, a desk, a bed, a telephone – I know exactly what they are. I know it’s a chair – but the word won’t come to me. I can’t say it. Tze’ela has this patient smile. Behind that smile she hides the secret password needed to enter the world called ‘Hebrew.’ I used to know that password too. Not any more. I lost it. For the life of me, I can’t remember what it is. And it’s not just the password, I lost language itself, too. It’s gone. That thing that makes you feel that you’re part of a group, that you’re in on a secret. That makes you smile when you hear familiar Hebrew words spoken in a distant land, when someone you don’t even know speaks your language. I used to be part of all that. Now I’m not. They are. They know. I don’t. Tze’ela begins.

Tze’ela: Shall we?

Doron Nesher: She seems nice enough. She has a tiny lisp. It’s something in her lip, I think. I’m not sure I have the patience for this today but then again, I don’t really have a choice. And I trust her. She’s probably coached many people like me before. Guided them through the labyrinth we call ‘talking.’

Tze’ela: Let’s start with some simple words.

Doron Nesher: She pulls out a folder with pictures and shows them to me one after the other. She asks me to identify and name them. They are simple objects – hammer, fork, light bulb – and I get that this should be child’s play. There’s another one – it’s like a seedling but taller. Kind of a plant… But with arms. Leaves. It’s big. Very big. What the hell is it called? It’s a simple word, I know that. It’s a word people use frequently. I know it. I know that I know it. But I can’t find it.

Tze’ela: It’s OK, let’s move on.

Doron: No!

Doron Nesher: I yell.

Doron: Wait a minute.

Doron Nesher: I look around. I gaze out the window and see it. I can point at it, but I can’t name it. I’m so frustrated that I start tearing up. It doesn’t help. She crosses her legs. It’s a tiny gesture of impatience that she lets slip. But I understand. I’d be impatient too. She taps the table with her pinky. I have no idea how this works. Do I move my tongue? My lips? When do I release the air from my lungs? How does this work? What comes first? And why can’t I do it? Then suddenly…

Doron: Etz, tree!

Tze’ela: What did you say?

Doron: “T…T…Tree!”

Tze’ela: Yes, very good Doron! Very good!

Doron Nesher: We look at each other, letting the feeling of victory wash over us. No one will ever know about this triumph.

Doron: Thanks.

Doron Nesher: Honestly, it was a guess. I wasn’t sure I had the right word but I just went for it. I gambled and it paid off big time. I feel like I just completed a treacherous three-day trek. Tze’ela shows me another picture. It’s some kind of tool. Not a broom… It’s used for… something. Not gardening but rather… cutting things in half. No matter how hard I think, the word doesn’t come to me. I can see two workers holding this object at each of its ends. They move it back and forth and it cuts. I know this tool, I know it. But nothing. It took me ages to re-learn ‘telephone’ as well. And then one day, as if with the flick of a switch, the light behind the word ‘telephone’ turned on. Te-le-phone. I was so happy when that word came back to me. I felt like a magician. But this object in front of me now… This tool moving forwards and backwards – it’s still dark. Still stuck.

Tze’ela: It’s OK.

Doron Nesher: Tze’ela tries to comfort me.

Tze’ela: We’ll come back to it later.

Doron Nesher: But my sense of failure ruins the next word for me too. It’s a picture of a tool again. But a different tool. This one you can work with. You can also kill with it. I close my eyes, and try to concentrate. I can hear Tze’ela say something but I gesture to her with my hand.

Doron: Just give me a second!

Doron Nesher: I have to solve this one. Then all of a sudden, out of nowhere, she starts yelling at me.

Tze’ela: If you don’t get this in ten seconds you will pay for every single word you forget! Do you hear me? Do you understand what I’m saying?!

Doron Nesher: She has a glint of crazy in her eyes.

Tze’ela: Behind each card there’s a number. If you get a word wrong, that’s the number of days you’ll spend in solitary confinement.

Doron Nesher: I wake up.

Tze’ela: It’s OK.

Doron Nesher: Tze’ela smiles as usual.

Tze’ela: Do you want to stop for today?

Doron: How long have I been sleeping?

Tze’ela: Oh, just about two minutes.

Doron: That’s it?

Tze’ela: Yeah, it’s OK. Really. I know how taxing this is. Why don’t you go wash your face?

Doron Nesher: I do. The cold water calms me down.

Doron: I’d like to give it another try.

Doron Nesher: She picks up a card. There it is. That tool again. The two workers.

Tze’ela: Say whatever comes to mind.

Doron Nesher: Tze’ela encourages me.

Tze’ela: Just blurt it out…

Doron Nesher: I stare at the picture, and try.

Doron: I see a nice man. A builder. He’s got a toolbelt with all his tools dangling around. He’s making these motions – back and forth, back and forth.. He’s working very hard. It’s a… different word. A special word. In the mountains.

Tze’ela: Say whatever comes to mind.

Doron Nesher: I force air out and exhale.

[Doron breaths heavily]

Tze’ela: OK, let’s stop for today. Really, it’s OK.

Doron: Du-Chi-Fat, HOO-POE!

Doron Nesher: I yell.

Tze’ela: What?

Doron: Hoo-Poe! [both laughs].

Doron Nesher: I burst out laughing. Tze’ela is laughing too.

Tze’ela: Why are you laughing?

Doron: I don’t know.

Tze’ela: Do you know what a hoopoe is?

Doron: No.

Tze’ela: Not at all?

Doron: It’s something in nature.

Tze’ela: Right, but what in nature?

Doron: Maybe a bird?

Tze’ela: Yes. A special bird.

Doron: A strange bird.

Tze’ela: Yes, exactly. Have you ever used that word before?

Doron: I don’t think so.

Tze’ela: So why did you say hoopoe?

Doron: Cuz’ you told me to. You said, ‘say whatever comes to mind.’ And that’s what came to mind.

Tze’ela: Have you ever seen a hoopoe bird?

Doron: I think so.

Tze’ela: When?

Doron: At school.

Tze’ela: When you were a boy?

Doron: Yes.

Tze’ela: And what did you think when you heard that word – “hoopoe”?

Doron: I’m not sure… Just that it’s… a special word.

Tze’ela: Special how?

Doron: It’s… It’s… different from all the other words you’ve asked me to say. It’s more special than “desk” or “chair.” It comes from far away. From a high place. A distant land. Where houses are made out of logs. Where builders mark the wood with pencils they keep behind their ears.

Doron Nesher: I’m exhausted.

Doron: Sorry again for falling asleep.

Doron Nesher: I close the notebook with the lined pages and slide it into my bag. She puts away all her “tools” – the hammers, the ladders, the trees, and pencils. All I want is to go to bed.

I turn my wheelchair towards the door, but stop before I leave.

Tze’ela: Did you forget anything? Doron?

Doron Nesher: Suddenly, I see a man. A man from long ago. The man who played that tool as if it was a musical instrument – even though it wasn’t a musical instrument at all. He was holding it between his knees, bending it and strumming it with a bow, getting it to produce all kinds of weird sounds. It was in Kibbutz Ramat HaKovesh, I now remember. I was there filming. All these kids were sitting around him. They were wearing orange t-shirts. Maybe it was a summer camp? It was a group, and they had a name. And this man… he was playing his non-instrument for them.

Tze’ela: Doron? Is everything OK?

Doron: That man… He was playing… a… s… s… saw.

Tze’ela: What did you say?

Doron: A “saw”! He was playing a “saw”! And those kids – they were a group of scouts… And their group, it was called duchifat, hoopoe.

Mishy Harman (narration): That association, between the word masor or saw and duchifat or hoopoe, dated back to 1981, more than thirty years before the session in Tze’ela’s office. Doron had been shooting a scene for a film on the main lawn of Kibbutz Ramat HaKovesh. There was a group of kids, their group’s name was duchifat – duchifat (or hoopoe) is Israel’s national bird, by the way – and in the middle of the group was a man playing on a saw.

Doron Nesher: Now listen, you have to understand that that association between a saw and the word duchifat was buried there, somewhere in my subconscious, since 1981. I was shocked.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yishai Golan and Gilia Shtern Nechmad with Doron Nesher’s story, Duchifat, which is part of his amazing memoir HaMoach Sheli Va’ani, or My Brain and I. The book, which I highly highly recommend, is in Hebrew, but Yochai Maital translated this story, and also produced and sound-designed the piece. Our dubber was Dan Gold. The beautiful original scoring is by the one and only Or Matias, and a special thanks to Jules Lawrence who played the saw for the piece. Yes yes, that weird wavy instrument you heard playing at the end was actually a saw!

Mishy Harman: OK, we are here at Har HaMenuchot cemetery in Givat Shaul, in Jerusalem. Trying to find the right entrance…

Waze: Continue straight.

Mishy Harman (narration): So I promised you one last chapter, one final twist, in the tragic tale of Shmulik Landau, the Chief Caretaker at the Israeli Wildlife Hospital at the Safari in Ramat Gan, who – several months after we spent the day releasing wild birds with him – took his own life.

Adina Karpuj: [In Hebrew] Joseph Gate. Benjamin Gate. Judah Gate.

Waze: Sharp left. Your destination will be on the left.

Mishy Harman: OK, here we are.

Adina Karpuj: Let’s go.

Mishy Harman: [In Hebrew] Hey, are you Shmuel?

Shmuel Kadoshi: [In Hebrew] I am.

Mishy Harman: [In Hebrew] Hi

Shmuel Kadoshi: [In Hebrew] Hi. I am Shmuel Kadoshi… [goes under].

Mishy Harman (narration): Shmuel Kadoshi is a ranger in the Park’s Authority. He also, just by chance, happened to be Shmulik Landau’s classmate in high school. Last April, Shmuel got a call from a contractor overseeing a building project in the cemetery. The contractor told him that an o’ach, an eagle-owl, had created a nest in an open grave in one of the cemetery’s wall burials.

Shmuel Kadoshi: [In Hebrew] I didn’t understand at first. What do you mean inside a grave? So we came here [goes under].

Mishy Harman (narration): Like the good ranger that he is, Shmuel showed up.

Shmuel Kadoshi: [In Hebrew] It nested in an empty grave. It laid eggs in the grave.

Mishy Harman (narration): Just to discover that this eagle-owl had indeed made its nest and laid five eggs in an empty grave right above Shmulik’s final resting place.

Shmuel Kadoshi: [In Hebrew] Wow, it’s in the same structure. The exact same structure, above Shmulik’s grave.

Mishy Harman (narration): Eagle-owl nests are rarely spotted, Shmuel told me, especially within a city. And there are more than 580 dunams and roughly 200,000 graves at Har MaMenuchot cemetery. So, believe what you want, but this is one hell of a coincidence. When the story came out, thousands of Israelis posted thoughts on reincarnation. Shmuel, the ranger, who’s religious by the way, isn’t sure what to make of it.

Shmuel Kadoshi: [In Hebrew] It’s some sort of full circle. An emotional full circle.

Mishy Harman (narration): He calls it a sgirat ma’agal, the closing of a circle. A continuation of what Shmulik did in his lifetime. The eerie fact that the bird nested right on top of Shmulik is less about mysticism. That’s not it, he says. It’s more the memories, the eternal things we leave behind in this world, that’s what’s moving for him. Eli, Shmulik’s brother, basically agrees.

Eli Landau: I have to say that, it is not excite me the story about the bird because, you know, he could be anywhere.

Mishy Harman (narration): Eli’s wife Sarah, Shmulik’s sister-in-law, sees it differently.

Sarah Landau: I just want to say one thing that very important to me about the bird and the nest. Because Eli doesn’t believe [laughs]. He doesn’t understand what is a big issue about this nest. But I believe that people wants… they want closure. They want to know that the person that they love didn’t leave them when he died. That the soul can send us some signs. Now, I totally agree with Eli that Shmulik would have laugh about what I’m saying now. But there are a lot of people, I believe, like me, that find very… a lot of meaningful in those kind of stories.

Eli Landau: It doesn’t matter what I think about the fact, OK? The important thing is the feelings and if people think that it is meaningful, so it is.

Zev Levi scored and sound designed this episode with music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Yishai Golan and Gilia Shtern Nechmad read Doron Nesher’s story, Duchifat, which is part of his memoir HaMoach Sheli Va’ani (“My Brain and I”). Yochai Maital translated this story into English, and also produced and sound-designed the piece. Our dubbers were Dan Gold (“Duchifat”) and Mitch Ginsburg (“Shmulik’s Letting Go”). The original scoring for the piece is Or Matias. Thanks to David Horovitz, Mick Weinstein, Theo Canter, Shlomit Berman, Matt Litman, Shai Doron, Roni Elias and Sasha Foer.