From our relationship with Ira Glass to priceless antiquities all the way to coveted sick passes – Israeli stories that are anything but real. In our very first episode, the Israel Story team delves into the realm of fakes, forgeries, and mimicry. Three stories, from different periods and places, of people pretending to to be something they are not.

Mishy Harman talks to Ira Glass, host of the popular podcast This American Life, about what it feels like to have an Israeli copycat.

Mishy Harman: Hey, and welcome to the very first English episode of Sipur Israeli, or Israel Story, here on Vox Tablet. I’m Mishy Harman, hi hi, and well, maybe the simplest way of introducing what we we’ll be doing here on the show is to play you something.

Ira Glass: Hey Mishy?

Mishy Harman: Yeah… hi!

Ira Glass: Hi! OK, it seems like we’re recording and and everything is going beautifully over here.

Mishy Harman: That, in case you don’t recognize the voice, is Ira Glass, the host of This American Life, one of *the* most popular radio shows in the States. I wanted to check in with him about some important business.

Mishy Harman: So Ira, how did you feel when you heard that there was this Israeli copycat?

Ira Glass: I felt fine about it. I felt flattered.

Mishy Harman: I don’t know if you remember this, but the first time we met, I came into your office, and you know, I was kind of starstruck, and really excited, and I walked into your office and, do you remember what happened?

Ira Glass: I totally remember. I said to you, like “oh, are you the Israelis who are ripping off our show?”

Mishy Harman: [laughs]

Ira Glass: I had heard about you.

Mishy Harman: And is that how you felt, that we were the Israelis who were ripping off your show?

Ira Glass: Well, it isn’t a question of how I feel, that’s just a statement of fact. You are the Israelis who are ripping off our show.

Mishy Harman: So yeah, that’s us. My best friend Roee and I were huge This American Life fans in college, and when we came back to Israel to begin our PhDs, we thought we would give it a try. An Israeli This American Life. We teamed up with two old childhood friends, Yochai and Shai, and began working on a podcast. And honestly, at most, we expected our family and friends to indulge us, give it a listen and hopefully pat us on the back. And that’s exactly what happened after our first episode. But then someone with like 5000 facebook friends shared the second episode, and it kind of went viral.

Now, I know, this sounds a bit like North Korea, but Israel has only two national talk radio stations one belongs to the government, and the other to the army. So just about then, I saw the head of the Army Radio, Galey Tzahal, at some event in Jerusalem. I totally ambushed him, and, while he was gobbling down some pigs in a blanket, I pitched our show. Somehow, amazingly, it worked. They agreed to run a pilot and then gave us one of the most listenedto slots of the week. Our first season had eleven episodes, and before we knew it, actually had quite a few fans. Now, this coming weekend actually, our second season in Hebrew will go on air. Working on the show we’ve met amazing people, and heard funny, touching, and incredible stories. So we began thinking about bringing some of these stories abroad, to people who believe it or not still don’t speak Hebrew. Lucky for us, Tablet Magazine loved the idea. So here we are, once a month for the next six months, bringing you stories by and about Israelis. You won’t hear about Bibi, the war in Gaza, or the Iranian bomb. Instead, it will just be regular, everyday stories, of an Israel people rarely encounter. Typically, we’ll have a theme, and several stories about that theme. And today, in honor of our attempt to create the This American Life of Israel, our theme is: “Fakin’ It.”

There’s this Simpsons episode where Lisa is trying to rack up extracurriculars to get into college. When it turns out she sucks at fencing, Marge tries to cheer her up.

Marge Simpson: Sweetie, you could still go to McGill, the Harvard of Canada.

Lisa Simpson: Anything that’s the something of the something isn’t really the anything of anything.

Mishy Harman: Here’s Ira again.

Ira Glass: [laughs] Yeah, so you’re you’re feeling that about like being the This American Life of Israel. That’s what you feel? I mean the fact is, like what does it mean to be the This American Life of Israel? It just means you’re doing narrative stories with characters and funny moments, and moments where there’s some feeling… I mean I don’t… like we own that as a radio show. Like, that’s why it didn’t bother me that there would be an Israeli knockoff of This American Life. [laughs]. Like, like, I hope that isn’t mean to say that, but like it didn’t… That seems good. If there was Korean one and a Japanese one and a British one that would all be… That’s fine with me. I don’t care.

In nineteenth century Jerusalem, Moses Wilhelm Shapira created fanciful forgeries that shook the world. But even today, 130 years later, no one is quite sure what to make of them. Fake? Real? Both?

The only known photograph of Shapira |

British cartoon of Shapira (on the right) |

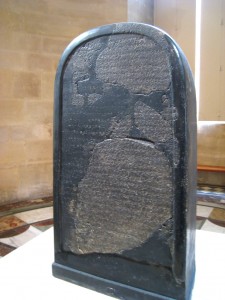

The Mesha Stele |

Mishy Harman: With that let’s begin. Today we have three stories of people, in completely different contexts and periods, trying to fake, pretend, mimic, forge. Whatever you want to call it. In the spirit of total emulation, act one ‘Truly Fake’. Depending on who you talk to, Moshe Moses Wilhelm Shapira is either a trickster of epic proportions, or the most unlucky fellow you can imagine. His story came to be known as the Shapira Affair, and many people are completely absorbed with it. Micha Shagrir is one of them. He’s making a documentary film about Shapira, and gives us the nutshell version.

Micha Shagrir: The time is 1883. A Jew from Jerusalem, actually a converted Jew, comes to London, to the British Museum. It sounds like a joke, but he brings with him fifteen scrolls on which, he’s claiming is original text of Deuteronomy. There is a big excitement. The museum offers him one million Pound. One million Pounds at 1883, it’s hundred of millions of Dollars today. But the museum people are saying that they still have to make some researches. And then they come back to him and say: “No business. We found your past. You are a forger. We even checked the text and the scrolls themselves. A forgery. The man leaves England, desperate, and after a year kills himself with a bullet in his head.

Mishy Harman: We always think that fake and real are opposites. You know, if something is fake, by definition it isn’t real, and viceversa. But, well. The story of Moshe Moses Wilhem Shapira shows us that sometimes reality is just more complicated than that. I didn’t know it when I began researching the story, but the Shapira Affair, or Shapiromania, as many of the people I talked to call it, continues to stir up really intense emotions, even though it took place more than a hundred and thirty years ago. Case in point, Micha Shagrir, a Jerusalem filmmaker.

Micha Shagrir: I am following for many many years. I am like a secret detective. Every day I think about him, or I do something that is related to his story. I go with him everywhere, and he is with me, in the archives, in the libraries, in Europe, in Israel, in Australia.

Mishy Harman: Without a single exception, when I called all the people I talked to for this piece collectors, professors, curators, archeologists, documentary filmmakers, and told them that I wanted to talk about Shapira they had the exact same response: “Ohho, Shapira… You have no idea what you’re getting yourself into.” And when I showed up at their houses to record, everyone, but everyone asked me to wait a second, and appeared a few minutes later, holding a stack of heavy folders full of pictures, newspaper clippings, articles, books and documents bursting out from every side.

Irit Salmon: You want to see the objects from, of, Shapira? I will show you. Aha, here you see one of his heads. Here, here’s the scrolls.

Micha Shagrir: And here, for example, photograph of Maria, Miriam, his daughter. And that’s Rosetta, the mother. And that’s Mr. Shapira himself. The only picture of him that I found till now.

Mishy Harman: It became completely clear to me that the Shapira Affair was very far from being settled. So, what are we talking about? In 1855, Moshe Shapira, a good Jew from an Orthodox family, left his home in the little Ukrainian village of KamyanetsPodilsky and set off on a long journey with his grandfather. They were going to the Holy Land, where, rumors had it, the Messiah was about to make an appearance. En route, somewhere in Romania, the grandpa died, and Shapira started mingling with all kinds of types. Most of them were representatives of an organization with a catchy name the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews. They promised him, with all their might, that the Messiah had actually already come. And that his name was Jesus. Moshe was slowly convinced, and when he arrived in Jerusalem a year later, he was a Christian and his name was now Moses Wilhelm. In Jerusalem he joined a small community of Protestants and converted Jews.

Buni Rubin: My name is Rehav Rubin, and I’m known by most friends as Buni.

Mishy Harman: Buni’s a professor of geography at the Hebrew University.

Buni Rubin: Well, there was in Jerusalem a group, kind of a social community of European people. Some of them were missionaries, other were scholars who were involved in the study of the history of the Holy Land.

Mishy Harman: But Shapira wasn’t really interested in the mission, or for that matter in research. He wanted to be a businessman, so he opened a small souvenir shop in the Christian Quarter of the Old City in Jerusalem. Irit Salmon, a true Shapirologist, who even curated an exhibit about him, explains.

Irit Salmon: Well, he had one of the first shops of antiquity in Jerusalem. So he sold everything which he could to the tourists. He sold Bibles, he sold dried flowers from the Holy Land, which the German pilgrims liked very much, and memorabilia from any kind. And he sold, as a matter of fact, the illusion that they touch history, because they grew on the Bible, and on the New Testament, and all of a sudden, they hold in their hands something which maybe also Jesus Christ kept it. So, it was very very strong.

Mishy Harman: In addition to those kinds of souvenirs, which still fill the shops of the Old City, Shapira also began selling antiquities that Bedouins from the area found, and brought to him. His shop was a huge hit, and he became one of the best known merchants in town.

Irit Salmon: It was a very famous shop. It was even written on the front of the shop that he’s the representative of the British Museum, not just a regular shop. In the Baedeker tourist guide from the nineteenth century, it was written that this is the best antique shop in Palestine.

Mishy Harman: Shapira’s life, as we say in Israel, was דבש, all honey: He married Rosetta, a devout German nurse, they had two girls Augusta and Miriam, and his business was booming. And then, one hot summer day in August 1868, a discovery made in Dibon, east of the Jordan River, changed his life. Local Bedouins had found a large basalt stone, inscribed with markings that sort of look like footprints of a chicken. Shapira rushed to see the stone, as did another archeology enthusiast a young French diplomat by the name of Charles ClermontGanneau who would, very quickly, turn out to be Shapira’s archnemesis. It seemed odd to the Bedouins that all these distinguished Europeans were so excited about the rock, and were fighting amongst themselves over who would pay a higher price to buy it. They were sure it had to contain some valuable treasure inside. So one night, they rolled the stone into a bonfire, poured cold water over it, and smashed it to smithereens. They were pretty disappointed. The crazy Europeans, it seemed, had been fighting over a plain black rock. No treasure. But ClermontGanneau had had his aid copy the inscriptions before it was smashed. And when he deciphered the lines, it turned out it really was a treasure. The thirtyfour lines on the Mesha Stele, that’s what they called the stone, described a series of wars between the King of Moab and the Israelites the exact same war described in the Second Book of Kings. Now, that might not sound super exciting today, but this was one of the very earliest external, independent accounts that verified a biblical tale. The craze around finding archeological ‘proof’ of the Bible, began. Everyone wanted Moabite artifacts.

Irit Salmon: Very soon, a tourist guide, Arabic tourist guide, came to him, after he opened the shop, and made him an offer he couldn’t resist. He said: “whatever you sell to the tourists during the day, I can complete during the night.” Which means to make fakes.

Mishy Harman: Here’s Buni Rubin, the geographer.

Buni Rubin: Well, we don’t know for sure. I can only make a guess, that if the demand was going up and up and up, and buyers could offer a lot of money, and they had a fairly lower ability to assess the authenticity or the quality of the antiquities, then a businessman like Shapira wanted to have enough stock in his shop in order to supply this demand for antiques, so I guess if he couldn’t get enough antiquities from proper sources, or kosher pieces, then it may well be that he thought how to supply this demand by producing, or actually faking, them.

Mishy Harman: Shapira saw the Moabite letters on the Mesha Stele…

Irit Salmon: And very soon, in the market, started to appear clay pieces with unknown letters, that nobody could read, which means he created a new culture which called Moabitika. He liked it very much and he started to get from the Bedouin who used to cross the Jordan and to bring all kind of antiques, part of them authentic.

Mishy Harman: Almost overnight, Shapira’s collection of Moabite clay artifacts became famous all over the world. Articles were written about it, new theories were based on it, people said the collection was priceless, and Shapira himself become a major celebrity within the antiquities world. But if you look at Shapira’s fakes today, even if you know nothing about archeology, they look like something that a fifth grader made in an arts and crafts workshop. It’s hard to imagine how these statues, figurines and ceramic human heads with gibberish inscriptions copied directly from the letters of the Mesha Stele, fooled the biggest experts of the time. But I guess we can be more forgiving. After all, they had nothing to compare it with, so most people just believed that that was what Moabite archeology looked like.

Irit Salmon: Today, when we look at those pieces, it looks so clumsy and so unprofessional, all the sticked letters, or the sculptures of heads of people, from stone, from clay. They look so strange, because nowhere there are pieces like that, or heads like that, or pieces of archeology like that. That’s why it was so easy to sell those objects because today, if you look at it, if I look at it, not professional, we would say “ah, this is a fake!” But at that time, nobody knew it, so nobody could identify it. Everybody wanted to believe.

Mishy Harman: And Shapira totally took advantage of that willingness to believe. In 1873 he convinced the Archeological Museum in Berlin, the Altes Museum, to buy 1700 pieces from his collection.

Irit Salmon: For those who were sceptic, he invited to come with him to an expedition. And he took them to the desert or to Transjordan, and the Bedouins prepared for him in advance, the area where he used to take them, as if they are going to excavated. And they just scratched the ground, and they found pieces of pottery and archeologic remains. And, he prepared the visit very very well.

Mishy Harman: The only problem with Shapira’s pieces was that they were, we’ve seen, completely bogus. But even today, there are people who don’t exactly see them that way. Uri Katz, a collector of Shapira fakes, for example, has a soft spot for Shapira, as kind of an original maverick, or biblical outsider artist, or something like that.

Uri Katz: The artifacts that he was selling, were really something new. It was not a copy of anything which we knew before. Shapira, or whoever made the artifacts, were some people of some originality, because they invented the artifacts. They invented the shape, and whatever. He created something new, in some way.

Mishy Harman: Micha, who we heard at the very beginning, and who is in the middle of shooting a documentary film about Shapira, basically agrees.

Micha Shagrir: No, he was not a chronical swindler. He was not a real swindler. But yes, he had his tricks.

Mishy Harman: When the folks at the Berlin Museum realized the artifact’s true nature, so to speak, they weren’t amused. They were embarrassed, and immediately hid the artifacts deep in the storage rooms. Of course the man who proved to the experts in Berlin that these were all fakes was none other than Shapira’s biggest rival, ClermontGanneau. Once the forgery was discovered, Shapira and his collection became sort of a laughing stock. He returned to his shop, and to the simple, silly souvenirs. But, as happens, time passed. And people began to forget the saga.

A few years later, his tarnished reputation almost completely rehabilitated, Shapira came out with a declaration that immediately rocked the entire world. He claimed that he held seventeen parchment scrolls inscribed with an unknown version of the book of Deuteronomy, the final book of the Torah, written in an early Hebrew script. Perhaps these were the original scrolls that Moses received from God, he hinted, or maybe a version written down at the time of Jesus, by a retiring sect in the Judean Desert, where, he said, the Bedouins who brought him the scrolls, had found them. Obviously, this was huge. The book of Deuteronomy! Maybe Moses’ own personal copy?! But there was one even more mindblowing surprise. Here’s Micha, the filmmaker.

Micha Shagrir: In the book that Shapira brought, there are eleven commandments. What is the eleventh? Do love your friend as you love yourself. Love thy neighbor. What does it mean? Is it a very Jewish version, or is it a very Christian version?

Mishy Harman: He toured all of Europe with his scrolls, and, you gotta understand, this was front page news in all the biggest newspapers around the continent for an entire year. The whole world, it seemed, was following the saga of Shapira and his precious scrolls.

Irit Salmon: He brought it to the German. And the German, as you remember, bought already 1700 fake pieces from him, and after few months, they thought about it, and they decided not to buy it. And then he came to the British Museum. They believed him. The British were VERY excited from it, because they loved the Bible.

Mishy Harman: Two of the scrolls were exhibited to the excited public, who queued up for hours to get a peek. Even the British Prime Minister, Gladstone, came to see them and tried to help raise the funds.

Irit Salmon: The sum of money he asked was unbelievable. Million Sterling in 1883! Today it’s also a lot of money, but then it was, phew… In fact, he said to his daughter before he went to his last journey: “When I come back, you will be the richest girl in the world.”

Mishy Harman: But then, of course, our French friend, ClermontGanneau, rushed over from Paris.

Uri Katz: Despite the fact that there was no tunnel, and no fast train, but it was fast enough to, from one day to the other. Irit Salmon: Then, Clermont Ganneau arrived. The same Clermont Ganneau which we met before in Jerusalem. Clermont Ganneau came, he looked at the scrolls, and then he said, “this is forgery.”

Irit Salmon: And he said that it’s the most chutzpadic fake in the history.

Uri Katz: [Laughs], yes.

Irit Salmon: The British press was wild. The story was everywhere, they didn’t stop to write about it day and night, in all the newspapers.

Uri Katz: The English got cold feet and they told Shapira, “sorry, we do not take the scrolls.”

Mishy Harman: Even for a tough survivor like Shapira this was a really hard hit.

Irit Salmon: He went from place to place, from country to country, all over Europe. And in March ‘84, he arrived to a small hotel in Rotterdam and committed suicide.

Mishy Harman: And what happened to the scrolls that caused a worldwide frenzy, and were nearly sold for a million Pounds?

Irit Salmon: The scroll afterwards were sold in a fair, to a collector who bought it for sixteen Sterling. And they say that his library was burned, and they were never found.

Mishy Harman: End of the story? Well, not exactly. A little more than sixty years after Shapira killed himself in that Rotterdam motel, disgraced, humiliated and penniless, a Bedouin shepherd, Muhammed EdhDhib, was out grazing his flock near Qumran, in the north of the Dead Sea. When one of his sheep ran into a cave and wouldn’t come back, the shepherd threw a little rock which hit something that made a strange sound. That’s how the Dead Sea Scrolls were found. Exactly in the same area where Shapira claimed that the Bedouins had found his scrolls. A new, completely horrifying, possibility, emerged. Could it be that Shapira’s scrolls, that were maligned and destroyed, were real after all?

Buni Rubin: To be really honest, there is a small, a tiny, like this, “what if.” And what if these pieces, which are lost now, were not faked? What if part of them was authentic? Then we lost something which might have been very very important. How can we know? How can we ever know how to deal, how to work out, this tiny little what if? The tiny what if, I think, will be an open question for ever. We’ll never know. And the what if will stand, I guess.

Uri Katz: [Laughs]. It remains a secret, and it will remain, I’m afraid. This will keep us on, continuing to ask ourselves, was it a fake or not. As a matter of fact, in my mind, the wonderful things is that there is no way to find physically the artifacts, the strips. The story of the scrolls remains unsolved. And I’m… I like it this way. It’s not our job to solve everything and I like it to remain as it is.

Mishy Harman: In one final, ironic twist that only a forger like Shapira would really appreciate, his fakes have now themselves become very valuable collectors items. In fact, today people talk of real Shapira fakes. And that’s what Irit Salmon called her exhibit about him. Truly Fake.

Irit Salmon: I think it’s a great name. In English it’s “Truly Fake,” and in Hebrew Ziuf Amiti, because it was really fake [laughs], so it’s a real fake.

Mishy Harman: And who knows, maybe somewhere in a back room workshop of a souvenir store in the narrow streets of Jerusalem’s bustling Christian Quarter, someone right now is sitting down and making fake Shapira fakes.

An IDF cadet proves that there basically isn’t anything we wouldn’t do for love. Yochai Maital with a story of deception, pain, and passion for one curly-haired American girl.

Act Transcript

Mishy Harman: There’s something you should probably know about before we begin this next story. And that thing is called ‘gimelim.’ Gimelim are sick days from the army, and, believe it or not, in the land of StartUp Nation and perennial peace talks, they are pretty much the most coveted item out there. If you think I’m exaggerating, I’ll just say that even Google backs me up on this one. The second most asked ‘how to’ question in Google in Hebrew last year was – yup – “how do I get gimelim?” Getting gimelim has practically become its own art form, some schmeer toothpaste or dishsoap in their eyes, others drink a mixture of cigarette ashes and chalk, and the most masochistic ones, those who I guess will really do anything at all to get a few days off, tie a potato to their arm or leg overnight. It sucks up all the calcium, and then, with a little tap of a spoon, they break their bones. Yochai Maital, one of the producers of our show, tried a different approach. Act II “Buzz Kill.”

Yochai Maital: About two and a half years into my IDF army service, after a particularly grueling couple of months of training, I got a regila a week long vacation, to go and rest at home. On the first morning of my regila, I woke up in my own bed, at home in Haifa. It was late, and no one was home. I stretched, made myself a cup of coffee and went to sit outside on the porch. I was completely relaxed, and savoring every moment of this rare freedom. That’s when the phone rang.

Now, this is never really a good sign. Nothing good has ever come from a phone ringing just when you are finally in some kind of zen moment. So I picked it up with more than a bit of trepidation. But it wasn’t, as I feared, my commander calling me back to the base. On the the other end of the line was Mollie, an American girl I knew from summer camps growing up.

Mollie had always been this sort of out-of-my-league kind of dream. And here she was. On the phone. With me! And, as she kept talking, my heart rate steadily increased, because what she was saying was nothing short of miracle: She was in Israel for a Junior Year abroad, it turned out, and all of her close friends were, like me, too busy in the army to hang out with her. She was dying to go on a tiyul, an outdoor hike, maybe a trip to the north, and wanted to know if I had any free time. In a very lame attempt to sound matteroffact, I managed to squeeze a meek “sure” and before I even finished my coffee, Mollie was on a bus to Haifa.

I, on the other hand, went into full panic mode. I ran around the house trying to put together everything a young Israeli guy needs in order to impress an American girl. I was a soldier, and needed to show off my wilderness prowess and ruggedness. So I strung together a camping stove, cast iron pots, strong black coffee. I begged my parents for the car, threw everything in the trunk, and on the way to the station, called a friend from a kibbutz in the north and pleaded with him to reveal the location of a couple secluded secret springs in the area.

I pulled into the central station, and just as I was rehearsing my opening lines one last time, I saw her big mane of curly brown hair heading in my direction. Smiling.

Despite the last-minuteness of it all, the trip was a huge success beautiful and romantic. I played the role to perfection. I took her to a hidden pond east of the Jordan River, where you can jump something like fifteen meters from a cliff into the water. Of course, I had to impress her. So I jumped. But when a few second later I looked up and saw her flying in the air too, right after me, I knew I was in love. I could even imagine the cheesy Hollywood soundtrack.

At the end of that week, I headed back to the my army base all dreamy and euphoric, grinning from ear to ear. One of those people it’s super annoying to be around. But my commanding officer found a quick way to wipe the constant smile off my face “Yochai,” he called me over, “you’re going to officer’s’ training.”

Now, basically the last thing I wanted at that point was to go to officers’ course. I had just fallen hopelessly for a girl who was only going to be in Israel for a few short months, and everyone knew that officers’ training, which was tucked away in some godforsaken base down south near Miztpe Ramon, sucked as far as vacations were concerned. But my commander’s face made it clear that it wasn’t exactly a suggestion… The next day, I was in the middle of the desert.

Rumor has it, that ‘Bahad Echad’ that’s what the cadet school is called was built according to blueprints of an American prison. The bare concrete buildings form a square around a central yard. There are guard towers in each corner, and the head commander’s office, with its big windows, overlooks it all.

It would be more than four weeks before my first vacation, and I roamed around the base feeling trapped and depressed. Basically, I was in jail. And Mollie, well, she was out there. In the real world. In Jerusalem. Hanging out with friends and drinking ice coffees in the German Colony. In Behad Echad, on the other hand, the days, you can imagine, went by slowly. Way too slowly. I barely managed to drag myself from one boring warfare theory class, to another night of guarding remote ammunition bunkers. It all felt completely pointless. I chained smoked whole packets of Nobles, the cheap local brand, and watched the summer just wither away. At some point in the middle of this agonizing course, Mollie told me she was going back to the States the following week. And that would be that.

But suddenly I couldn’t tolerate another moment in this stupid officer’s course. I just had to see her one last time. And the only solution I could think of was getting gimmelim. A sick pass. But here’s the thing I was sort of a straight arrow, highly motivated, kind of nerdy by-the-book soldier. I would get punished because I would do things like report that I had misplaced my helmet or sat down for five minutes while guarding. Things that no one would have ever known. Needless to say, I was kind of clueless when it came to getting fake gimmelim. I called my good friend Ariel.

Ariel Harpaz: I remember that just hearing your request, I thought to myself this is serious, you must really be into this chick.

Yochai Maital: Ariel is the type of friend you can call with any problem, at any time of the day. Especially if it involved the chance to gaming the system.

Ariel Harpaz: I always thought of you as this kind of upstanding, ‘perfect’ soldier, you know, and here you were, instead of excelling in officers’ course, you were trying to screw them and get all these gimilim. Gotta say, I was kind of proud. I thought that after all, maybe I taught you something.

Yochai Maital: Ariel swore me to absolute secrecy, and told me to meet him outside the base at one am that night at one am.

Ariel Harpaz: A friend of my uncle’s was a sort of bee therapist in Shilo, a little settlement in the West Bank. Yeah, bee therapy, it’s sort of like acupuncture, you know, like a Chinese doctor, but instead of sticking needles, he gets the bees to sting you. The guy had all these beehives in his backyard, and he would catch a bee with these long wooden tweezers, and hold it to your skin, then it would inject its poison into you, and after a few hours the whole area would swell up. And just around that same time, a miracle happened my parents got these wooden tweezers as a gift, you know the kind The Americans use to take bread out of the toaster or something. You know about the problem with how you’re not supposed to stick a metal fork in the toaster?

Yochai Maital: So Ariel adopted his uncle’s friend’s idea, and instead of using the tweezers to get the toast out of the toaster, he used them to help his friends get some gimmelim. Turned out he had done this before. I wasn’t his first client.

Ariel Harpaz: In those days, I knew where all the beehives in the Jerusalem area were. So I’d come at night with the guy who wanted gimmelim, walk right up to the hive, catch a bee or two and sting him. You see, I would always bring the patient to the beehive, but you were stuck in the south. I wasn’t really sure what to do, how I was going to handle it.

Yochai Maital: But Ariel wasn’t one to give up. The method was full proof, he thought. And it would work anywhere. So he waited for nightfall, when the bees were drowsy, drove up to a hive on a Kibbutz on the way, collected a few bees into a plastic bag, and headed south. But an hour into the drive, he noticed that the bees had stopped buzzing. They were dead. He turned the car around, drove back to the Kibbutz, and this time he found some jar to put them in, and learning his lesson, poked a few holes in the lid. With a new set of bees on board, Ariel was off to save me. Not all the bees survived the ride, but I guess he had counted on there being some casualties. As for me, I had no idea what Ariel’s plan was. All I knew was that I had to meet Ariel at the bus station outside of the base, at exactly one, and most importantly, Ariel kept stressing this point over and over.

Ariel Harpaz: The most important rule is not to talk to anyone about this. This was the biggest secret in the world.

Yochai Maital: I tried to concentrate on faking a kind of nonchalant confidence as I walked right out of the gate, too quickly for the guards to ask where I was going. Ariel was at the buss stop as promised, so was the buzzing jar. He was all business, evidently this was a delicate process.

Ariel Harpaz: You see, the problem was that we couldn’t risk you getting too many gimmelim because more than one week, and you’d automatically be expelled from the course, and you didn’t want that. So we had to get just the right amount, it was very tricky. Anyway I decided that instead of pricking you in the knee, which was the usual procedure, I would sting your foot.

Yochai Maital: I wish I could tell you that like a true officer, at that very moment in Ariel’s car, I considered all the consequences: Possibly getting kicked out of the course, maybe even out of my unit. But to be honest, I wasn’t thinking at all. The only thing going on in my mind was this stubborn determination to see Mollie one last time. So with his toast wooden tweezers, Ariel carefully plucked three exhausted bees, one after the other, from the jar. And each one of them sacrificed their life on the altar of my twenty-year-old horny-ness. Three pricks, on the exact same spot on my ankle. I waddled back to the base, got in bed and went to sleep.

I started burning up and hallucinating, a side effect from the all the bee venom. I imagined that Mollie appeared at my bedside, here in this awful base, holding my hand until I fell asleep. In my dream, I saw myself sitting high up in the stands above the central yard of the base. An military marching band was playing these patriotic songs. It was the graduation ceremony of the officers’ course. All my unit, and friends and family had shown up, only to discover that I had been kicked out of the course long ago. I woke up startled and sweaty. But when I looked down at my foot, a huge smile spread on my face: My ankle was the size of a watermelon.

I limped over to the infirmary where I told them that I had tripped and fallen down a flight of stairs. The medic took one look at my foot and sent me straight to the ER in Be’er Sheva, the closest big city. At the hospital, I waited impatiently as an elderly Russian orthopedic surgeon closely examined my x-rays. He stroked his Trotskyesque goatee for a while, turned to me and proclaimed. “Yup, just an I suspected. You have a broken foot.”

Now, up until this moment, I was fairly calm. Things were going exactly according to plan. But suddenly everything seemed to be going too well. A broken foot was serious. It was worth like a month of gimmelim. If not more. And I would be kicked out of the course for sure. I was still trying to formulate a plan of action when the doctor sat next to me and started casting my foot. But I wasn’t fast enough. Twenty minutes later I was at Be’er Sheva’s central bus station, with a cast all the way from my toes to my knee, and oh, yeah, two weeks of gimmelim, which, he said, would surely need to be renewed a few times.

But I was concentrated at the important task at hand: getting to see Mollie. It’s a two hour ride from Be’er Sheva to Jerusalem on the 446 bus. And, just around Kiriyat Gat, I had had it with this itchy cast. When no one was looking, I took out my pocketknife, and sawed the cast off. As soon as I got off the bus, I tossed it in some trash can.

This time it was Mollie who came to meet me at the station. My ankle was still huge, and she asked me about it. But I kept silent, just as promised. We went to the Machne Yehuda Market together, bought some vegetables and headed back to her apartment where I made us a potatoleek soup with Tom Waits singing in the background. A few days later, she flew back to the States, and I reappeared at the base sans cast begging them to let me return early. I mumbled something about how I gotten a second opinion, and how it turned out that the initial doctor had made a mistake. I had only sprained my ankle, but, apparently, all my bones were intact. Everyone at Bahad Echad were super impressed by my motivation and honesty, returning early from gimmelim. It was so unheard of, that they agreed to take me back.

Usually these stories end with a moral like cheating is bad or lying never pays off. Yada yada yada. But honestly, in this case, it did. I came out of this whole thing utterly unscathed. If anything, I learned the opposite lesson. For many years, I kept it a secret. Three tiny dots above my right ankle are my only reminder. Ultimately, I finished the course and became an officer. I became an officer. And even served for five more years. But I never, ever, faked a single gimmel again. I swear.

Mishy Harman: Yochai’s married now, not to Mollie, and even has a twoyearold daughter. Mollie’s also married, and lives in Brooklyn. We called her to see if she even remembers any of this saga. Turns out she totally does.

Mollie Andron: Yeah, when I want to sound like really awesome, yeah.. I tell this story. [laughs].

Noa Guy was a promising Israeli composer. When she came to New York twenty-one years ago to rehearse for a concert at Carnegie Hall, she never imagined it would become her permanent home. Shai Satran brings us her story.

Mishy Harman: Yochai’s self-inflicted injury was entirely superficial from the outside, it looked incredibly painful, but on the inside he was just fine. Better than fine, even. Our next story is pretty much the exact opposite. Noa Guy from Jerusalem was a world class composer. But twentyone years ago she suffered what she now refers to as a “transparent injury.” To anyone looking at her from the outside, she seemed completely fine, but on the inside, she was and still is anything but. Shai Satran brings us her story. Act III – “Disharmonia.”

Noa Guy: Hello, Shai!

Shai Satran: Hi, Noa.

Noa Guy: Hi!

Shai Satran: I met Noa Guy, an Israeli composer, in her Manhattan apartment.

Noa Guy: Well, when people ask me, “How did you end up in New York?” I always say, “by accident.”

Shai Satran: We’ll get back to how and why Noa ended up in New York, but our story starts in her hometown, Jerusalem.

Noa Guy: I was born in Jerusalem, and grew up there. And from very very early age was attracted to music, and studied music.

Shai Satran: The fact that Noa was so drawn to music was kind of surprising

Avner Goren: It’s hard to say how Noa becomes so much [enter music] into it.

Shai Satran: This is Avner, Noa’s brother.

Avner Goren: Our parents did not expose us to classical music.

Noa Guy: Our father was injured in the Independence War, and had, ah… Always had headaches. So… House has to be quiet.

Avner Goren: Any loud noise would disturb him a lot, and many times he would leave home just when Noa was playing, which was not very much encouraging. And, ah… in spite of that she was very stubborn and continued to practice, to learn more.

Noa Guy: So music was, in a way, sort of a noise, but ah… nevertheless I continued, and that was my passion. After high school, no question what I am going to do. I went to the Jerusalem Music Academy, finished the theory department. And then studied composition privately, and then moved to Berlin to study music there.

Shai Satran: After winning many international prizes, Noa moved back to Israel, and was appointed to be the Manager of the Jerusalem Music Academy, which, as you can imagine, is quite a big deal. And all in all, her career was booming.

Noa Guy: And, on ‘93, I came to work with Isaac Stern for a week.

Shai Satran: Noa’s week in New York was supposed to culminate with a concert at Carnegie Hall, a high point of any composer’s career. The first few days of the week, leading up to that concert were set aside for final rehearsals.

Noa Guy: On that day, which was a Thursday, we went to his country house in Connecticut, to work there, in, you know, a different environment, and quiet environment. I don’t remember really much since. It was country road, it was in the Fall, trees were burning colors, beautiful colors. Everything was a bit like a dreamy, in a way. I do remember, the last thing that I told Isaac that I think that he’s driving very very fast. And, he looked at me, you know, side-look, and he used to call me bubaleh, so he said “Bubaleh, don’t worry, I’m a very good driver.” That’s the last thing I remember.

Avner Goren: And on the way he hit a tree, and create a very severe injury to my sister. She just got out of the car, pull him out, and then collapsed and disappeared. She was evacuated to a New York hospital over there, and was in a coma for quite few days. And that came in a time that she was really getting into the peak of her career.

Shai Satran: She woke up eight days later.

Noa Guy: The first thing that I remember is that I was violated. That something really awful happened. I didn’t know where I was, I didn’t know where I was alive, or where I was dead. I was just seeing this halfwhite creatures hovering over me, touching me as if, you know, without asking permission. And, it was an awful way to wake up. I couldn’t make sense of anything. It’s really tempting to, to give up at this situation like that. But it was a decision not to, I’m gonna make it.

Avner Goren: But she made two decisions. One, to stay alive. Second one, was that she’ll be ok, and she’ll be able to function as a normal person.

Shai Satran: That second decision, to lead a normal life, would require tremendous efforts and many years.

Noa Guy: I was paralyzed on the whole right side of the body. You know, I had shoulder injury, hip injury, all kinds of injuries, but the main thing was the brain injury.

Avner Goren: She was then, with one of the physicians, they just put a pencil in front of her and asked her “What is that?” And, she could not say the word, she could not identify. And then I burst in tears and it was the first time for her to see me really cry.

Noa Guy: It’s not easy to explain, because after I got a little better and I was able to communicate, and I began to, to live again, people didn’t realize what really was going on. That for me to hear a sentence and remember the whole sentence and formulate an answer was an enormous task. And that’s why I call this a transparent injury, because from the outside I looked fine, I was talking, I was nice, I was smiling, I was polite. And inside it was this struggle to go on, not to, you know, not to let the injury shut me down, and… because it was so taxing.

Avner Goren: When we talk to each other now, and there is some background noise, we can ignore this noise. But she cannot. She has to process it through her mind, and decide what she had concentrate at. And that’s take a lot of energy, and very tiring.

Shai Satran: What Avner just described is a malfunction of sorts of Noa’s attention modification system. It can be explained through a famous psychological finding “The Cocktail Party Effect.” Imagine you’re chatting with someone at a cocktail party. There are many different background noises: Loud music is playing, the sounds of silverware, plates, glasses clinking, not to mention all the other conversations taking place all around. But, somehow, we sort of lower the volume on all those background sounds, and raise it on our friend’s voice. We don’t have to think about it. We’re not even conscious of it. It just happens . Basically, our brain is constantly filtering out a huge amount of stimuli that simply isn’t that important to us. Without these filters our brain would… overload.

Shai Satran: What does it feel like to sit in a noisy restaurant and just have a conversation with a friend?

Noa Guy: About half an hour after it begins, I have to leave, because it’s just bombarding me in, in a way that I’m so overwhelmed that at a certain point it’s too much. You know, when you talk to me, you listen to me and you’re not listening to the environment and for me, all the sounds are at the same level. It’s almost impossible to explain. It’s as if I’m on a stage and there’s floodlights all the time. There is nothing more important than the others. I can’t filter out things, cuz’ I lost the filters that we usually have of discerning what’s important and what not. It’s exhausting.

Shai Satran: This condition, of not being able to perceive, or focus on, more than a single object at a time, has a name, “simultagnosia.” It’s pretty rare, and most of the people who suffer from it, like Noa, experienced some sort of traumatic brain injury. But Noa’s case is particularly interesting to researchers, because her entire musical perception changed after the accident.

Noa Guy: The first piece I wanted to listen to was Beethoven’s string quartet. And, the first time I listened to it, I was blown away, because I didn’t hear a string quartet. I just heard four laser beams of sounds. They were very clear and totally disconnected. I couldn’t make sense of it. I couldn’t put it together. And I heard the violin, cello, viola, and I didn’t know what it was. It was like four parallel, independent lines, that wouldn’t connect. They were totally independent. It was like piece of puzzle, you know, just scattered on the table. And you know that if you put them in the right pattern they fit. I couldn’t do that. I heard it, I don’t know how many times. I heard it again and again, in the hope that I will be able to put them together. Couldn’t put it together.

Shai Satran: Oliver Sacks, the famous neurologist, dedicated a chapter to Noa in his 2007 book “Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain.” Sacks gave Noa’s condition a name Disharmonia the inability to integrate auditory components into a single harmony. Noa, of course, had devoted her life to music, and this was the worst injury she could imagine.

Noa Guy: In a way I think that if I would have lost a leg, it would have been easier for me. But the fact that I lost a major part of my identity, of my inner identity, and that I could not recreate it, is cruel, and painful, still today. At a certain point, you know, listening to it again and again, it became like a torture.

Shai Satran: Despite her disharmonia, Noa discovered that with substantial efforts she could still appreciate, and even create, music. For example, when Noa reads sheet music she can, in a sense, still imagine the music, at least in her mind, even though she can’t hear the music. It’s confusing. Her road to recovery was long, and full of hurdles.

Noa Guy: Today I can put things together, but it’s work. I have to do it consciously. It’s not that I put a piece of music and I hear the music. No, I… Now, I’m hearing the string quartet so, listen to them together. And I learned how to do that. But it’s still a conscious process. It used to be like language, it was, I wrote string quartets, I mean it’s ah… it wasn’t even a question. It was a pleasure, and it was my refuge.

Shai Satran: Noa had to relearn even the most basic skills.

Noa Guy: I bought a piano and I couldn’t play. And it was a shock. After trying and realizing that I’m not going to be able to do it alone, I swallowed my pride and I started taking piano lessons. I had to learn the eareyehand coordination. It was sort of a gift, because I realized how complicated piano playing is. But it was also very frustrating cuz’ I lost my ability to play. I lost this connection to music that I had, that I could sit and write music like you write a letter, and it was so easy, and everything was so enjoyable, and so fluent. And I think that’s the major thing that if you ask me something didn’t heal, this didn’t heal. Everything else is fine.

Shai Satran: Noa was stubborn. She learnt to play the piano again, and eventually even went back to composing. In 2006, thirteen years after that concert that should have been, Noa finally got her New York City debut.

Noa Guy: [enter music] I made three big pieces, hourlong each. Actually, it’s a musical diary of my recovery. So the first piece is from darkness to waking up, just broken pieces that are somehow put together and in the end are making some sort of sense. A friend of mine came afterwards and she said, “I know you for so many years, it’s the first time that I begin to understand what you’re going through.”

Shai Satran: At the beginning of the piece, you remember, Noa explained that she ended up in New York by “accident,” quite literally. What she didn’t say is that she hasn’t been back to Israel since that accident, over twenty years ago.

Avner Goren: Since then, she cannot travel, because all of her balance organs were destroyed, so she’s stuck, for life, in New York City, which is not bad. There are worst places to be stuck at.

Noa Guy: For a very long time, I thought that, well, another six months of therapy and I’ll be back home. I always wanted to go home.

Avner Goren: She didn’t make it back home. She didn’t see my father because he was sick and couldn’t travel, and she couldn’t travel, and he passed away quite few years ago. She could not be at her daughter’s wedding and things like that.

Noa Guy: And, it took many years of therapy and forgiving and accepting to realize, ok, I can’t go back. Israel is still, you know… I’m Israeli. But ah… It’s not painful anymore. But it used to be a real longing to come home. It took a lot of work to realize that a new beginning is the right approach, and not hanging on to the past, which is not available. I’m in a place that I don’t think that I would have been here, in this form, being able to look at things and see things and see the world in a way that I do. And a… In a, you know, topsy-turvy way, I’m grateful for it.

Mishy Harman: Aside from one Beethoven piece, and well Chumbawamba, all the music in that story was composed by Noa, who, from time to time, performs in New York. And, that’s it, our very first English episode.

Mishy Harman: Great well, Ira, I really hope that you listen to our show!

Ira Glass: I’m excited to hear the ones in English. That would be great.

Mishy Harman: Yeah.

Ira Glass: I said before that for me the only way that I could have listened to any of your stories in Hebrew is if you would have restricted the subject to the blessing over wine.

Mishy Harman: We were thinking of having a story which was solely the blessing over the wine.

Ira Glass: [laughs]

Mishy Harman: But we weren’t sure how popular that would be.

Ira Glass: Just that you’d do the blessing over the wine and somebody would be like “od pa’am ” and then they’d do it again. You know.

Mishy Harman: Exactly. Exactly. [both laugh]. Cool, well thanks so much, Ira, I really appreciate it.

Ira Glass: OK, thanks, OK, bye.