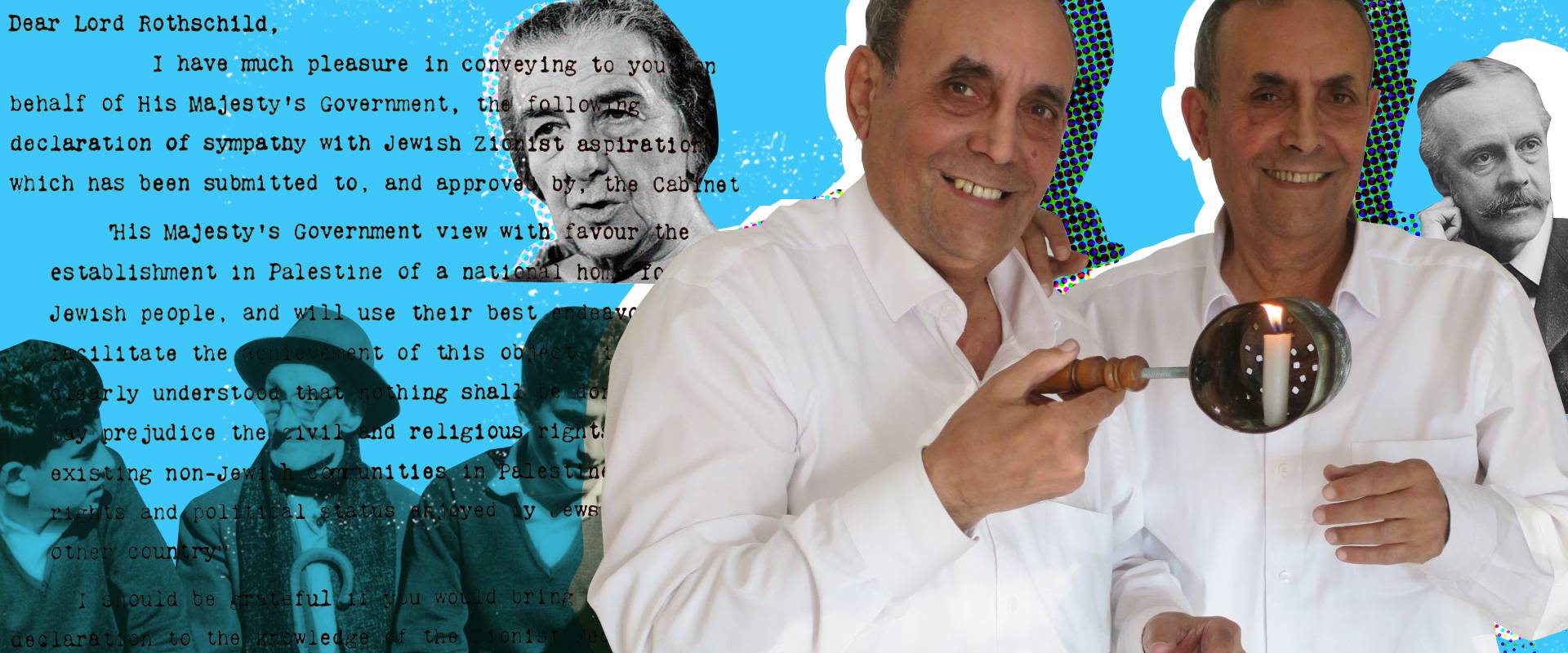

On November 2, 1917, Arthur James Balfour – Britain’s mustached Foreign Secretary – signed his name at the bottom of a short, typed letter addressed to a shy banker-turned-zoologist by the name of Lionel Walter Rothschild. “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,” it read. In the century since that fateful day, those words have reverberated around the world. They’ve changed reality, creating national dreams on the one hand, and squashing political aspirations on the other. And, of course, they’ve been scrutinized, analyzed and debated from every possible angle. The Balfour Declaration, for better or worse, is still very much with us. In a special commemorative episode, we set out on a less-than-intuitive journey in Balfour’s footsteps.

Prologue: His Majesty’s Government View With Favour

Mishy Harman tries to learn more about the famous declaration and its legacy by talking to three Israelis who spend a lot of time thinking about Balfour: Anita Shapira, Mahmoud Yazbak and Nirit Shalev Khalifa.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman (narration): There are a hundred-and-fifty-three insects, fifty-eight birds, seventeen mammals, three fish, three spiders, two reptiles, one millipede and one worm all named for Lionel Walter Rothschild. And who was this guy? Well, for starters, a Rothschild, from the British branch of the family. He was born in 1868, and told his parents – at the age of seven – that he would one day run a zoological museum. At first they indulged this hobby of his, buying him kangaroos and exotic birds. But ultimately they decided that enough was enough. Being an animal guy didn’t quite befit a scion of the illustrious financial dynasty. So they whisked him off to Cambridge, and – when he quit after just two years – they made him join the family business – international banking, that is. Walter, or should I say Lord Rothschild, never really loved the wheeling and dealing. Still, he was forced to stay at the bank, N.M. Rothschild and Sons, for nearly twenty years before he was allowed to pursue his true passion. It was only in 1908, at the age of forty, that his parents finally relented. But, as a compensation of sorts, they gave him the money to start his very own zoological collection. Even though a speech impediment made him quite shy, he was an extremely colorful man: He posed for a picture riding a giant tortoise, and – in an attempt to prove to Londoners that they could be tamed – he drove a chariot pulled by four majestic-looking zebras all the way to Buckingham Palace. Walter was a Conservative Member of Parliament, had a collection of more than two million butterflies, and – if that wasn’t enough – juggled two mistresses. But today, at least in Israel, Walter is remembered most for a short letter he received on November 2, 1917 – exactly one hundred years ago. “Dear Lord Rothschild,” it began. “I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet. His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country. I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation. Yours, Arthur James Balfour.” That’s it. The Balfour Declaration. A grand total of one-hundred-and-twenty-four carefully crafted, and intentionally vague, words that changed the fate of the Jewish people. Now, in the century since Balfour – Britain’s mustached Foreign Secretary – signed his name at the bottom of that Declaration, it has become one of the most scrutinized and debated documents around. What, people ask, exactly is a “national home”?

Anita Shapira: The ‘national home’ was a vague expression that could be interpreted as the power wished.

Mishy Harman (narration): Who are the mysteriously unnamed “non-Jewish communities”?

Mahmoud Yazbak: If you read the content as a Palestinian, you will see that you are not existing in this Declaration, because the Declaration talks about the Jewish people, but it doesn’t mention any sentence or any word, ‘Palestinian.’ That mean they are ignoring the Palestinian existence.

Mishy Harman (narration): And why was such an important diplomatic policy relayed in letter to a private citizen?

Nirit Shalev Khalifa: He was the most distinguished representative of the Jewish community. And in a way, you know, the Rothschilds, they were negotiating with governments, and with kings, and with rulers.

Mishy Harman (narration): Countless books, articles and films have analyzed the Balfour Declaration from every possible angle. This week, throughout the country, there are international conferences, public lectures, discussion groups, gala dinners and exhibition openings, all marking the centennial. So there are many people who spend a lot of time and energy thinking about Balfour and his legacy.

Anita Shapira: My name is Anita Shapira, professor emerita at Tel Aviv University in Jewish history.

Mahmoud Yazbak: I am Mahmoud Yazbak. I’m professor of Palestinian studies at the University of Haifa.

Nirit Shalev Khalifa: I’m Dr. Nirit Shalev Khalifa, and I’m a curator and art historian. And I’m now the curator of an exhibition about the Balfour Declaration that will take place in Jerusalem on November 2, this year. Hundred years exactly after the Balfour Declaration.

Mishy Harman (narration): I asked Anita Shapira – who’s written extensively on just about every aspect of the Zionist and Labor Movements – what, at the end of the day, was so important about this one letter.

Anita Shapira: The Balfour Declaration is the first declaration of a big power that recognizes the connection of the Jewish people, as a people, to the Land of Israel. It’s a turning point in Zionist history, no doubt about it, and in the history of the Jewish people. This is what gave the Jews the capability of establishing a state. And, as I am an Israeli patriot, I view it in the most favorable way.

Mishy Harman (narration): For Nirit Shalev Khalifa, the Balfour Declaration is the…

Nirit Shalev Khalifa: Starting point for the conflict between the Jews and Arabs in the Middle East.

Mishy Harman (narration): And indeed, Mahmoud Yazbak – an Israeli-Palestinian and an expert on 19th and 20th century Palestinian social history – has a different take on the whole matter.

Mahmoud Yazbak: The Balfour Declaration started a very important deterioration in the Palestinian history, which at the end resulted in the 1948 nakba, or crisis. Now, looking a hundred year later, after, you understand now that it was a very important moment in the Jewish history, in the Israeli history. But at the same time, this important moment in the Israeli history was a very disastrous moment in the Palestinian history.

Mishy Harman (narration): Yeah, different narratives. We know all about that. But everyone agrees on some basic facts: Towards the end of World War I, the mighty British Empire – then at the height of its power – decided to support the Zionist cause. They had many reasons for doing so – geopolitics, economics, trade considerations, immigration policies, religious sentiments, you name it.

Anita Shapira: What was behind the Declaration were British interests, as they were understood at that moment.

Mahmoud Yazbak: England at that time didn’t think that Palestinians would serve the interest of England, so they wanted somebody to come from outside the Middle East, to be planted in the Middle East in order to serve its political interests.

Mishy Harman (narration): Recognizing this window of opportunity, Dr. Chaim Weitzmann, a Zionist leader and biochemist working in Manchester, managed – with the help of others – to convince the Brits to put their support down in writing. This was a period of emerging nationalism, and timing was everything.

Anita Shapira: The First World War was one of the last moments in which the Great Powers could sit around the table, and draw new maps, completely out of the blue, completely without reference to the nations that were settled there etc. etc. For the Zionists this was an opportunity that had it not happened, I wonder if we would be sitting here today.

Mishy Harman: Had the Declaration not happened?

Anita Shapira: Yes.

Mishy Harman (narration): Everyone involved, including prominent Jews who opposed the idea, realized that it was an extremely delicate – and potentially explosive – matter. So there were many drafts of the Declaration, before it reached its final form.

Nirit Shalev Khalifa: Tens of people, worked for months.

Mishy Harman (narration): Every word was contested and evaluated. And the result – a document that is, Nirit says.

Nirit Shalev Khalifa: The basic for building the State of Israel.

Mishy Harman (narration): You see, even a century later, this brief letter still matters.

Nirit Shalev Khalifa: You have to show it, and you have to declare it all the time, and no one should forget it.

Mishy Harman (narration): And what about the tall, philosophically-inclined, British politician who scribbled his autograph at the bottom of the page? Who is Balfour today? Like anything in this country, it depends, of course, on who you ask.

Mishy Harman: Are you personally angry at Balfour?

Mahmoud Yazbak: Look, it’s not a matter of being angry or not. Balfour had given a land which is… doesn’t belong to him. I think it was big mistake that have been done for Palestinians.

Anita Shapira: He identified, with time, with the Zionist project in Palestine. He visited the country in 1925, he was vilified by the Arabs, and the more he was vilified, the more identified he was with the Jews.

Nirit Shalev Khalifa: He is a saint for the Jewish people. His face became like a Jewish icon.

Act I: Meet the Balfours

In London’s upper-crust circles, there are some people for whom Balfour is more than just a historical figure. He’s a source of pride, a daily presence, and… family. Danna Harman seeks out his living relatives, to get a sense of what it’s like to be a Balfour today.

Roddy Balfour: That’s the famous Lord Salisbury.

Danna Harman: Wait, I just… Just let me just say that we are in the bathroom. In the loo. [Roddy laughs].

Danna Harman (narration): So, I am ‘squooshed’ in here, in a very small bathroom, (or, as the Brits call it, the loo) in this fashionable apartment in Chelsea, London. It’s me, our elegant host, and our sound woman Shir, who – surprised our conversation is getting going in this location – whips out her iPhone to record. Our host is wearing a beautiful, soft gray suit, this understated, but expensive baby blue tie and a pocket handkerchief. He’s peering through horn rimmed glasses at framed caricature portraits from the last century hung on walls of the bathroom – giving us an introduction, so to speak, to the members of his aristocratic family.

Roddy Balfour: Oh well, all us Brits…

Danna Harman: Aha.

Roddy Balfour: Always keep these sort of things in our loos. We don’t sort of have them out and about.

Danna Harman: Why is that?

Roddy Balfour: I don’t know. It just is… It’s one of those sort of things. I think it’s not sort of showing off too much, you know.

Danna Harman: Aha.

Roddy Balfour: So that’s the famous Lord Salisbury, a wonderful picture of him. Then that is Arthur.

Danna Harman (narration): Arthur. As in Arthur James Balfour. Yes. The very same guy who penned the very aptly named Balfour Declaration. And our host here, drum roll please: Is none other than Lord Balfour himself.

Roddy Balfour: [laughs] Yes. That’s right.

Danna Harman (narration): OK, not the original Lord Balfour who sent the famous letter to Lord Rothschild. That one – Arthur James Balfour, known as AJB – was born in 1848. And he passed away, age 81 (an avid tennis player almost until the end) in 1930. So who is this Lord Balfour?

Roddy Balfour: I’m Arthur Balfour’s great great nephew, and he had no children so everything went sideways to his brothers and then down to me. So I’ve got the present mantle of being Lord Balfour. In many ways it’s a great honor and on certain occasions, it’s – I get all the blame.

Danna Harman (narration): Today’s Lord Balfour – friends call him Roddy – was born in 1948, like the State of Israel, a hundred years after his great great uncle. He works as an international tax advisor to wealthy families – and lives with his wife Tessa (that would be Lady Balfour) between this flat in London, and their family estate in Sussex, on the grounds of the one-thousand-year-old Arundel castle. There’s a lot going on the morning I visit: London traffic outside an open window, someone making tea in a back room, and a pop in from the lady of the house.

[comes up from under]

Roddy Balfour: And he had been born with, what as I would put it, Tess?

Tessa Balfour: Yes.

Danna Harman: Hi!

Roddy Balfour: Hi!

Tessa Balfour: Are you…?

Roddy Balfour: This is Danna. This is Tessa.

Danna Harman: Hi.

Danna Harman (narration): She immediately tells me about their recent trip to Israel.

Tessa Balfour: And we had a fantastic, an amazing time in Jerusalem. We were just… Ah! I was just… People came up to Rod and said, you know, “can I shake your hand?”

Danna Harman: I’m sure, I’m sure.

Tessa Balfour: And it was just an amazing experience for me actually. Any case, I won’t interrupt you anymore.

Danna Harman: Thank you so much.

Tessa Balfour: Lovely lovely to meet you both.

Danna Harman: Thanks.

Roddy Balfour: You’re off in a minute, are you my love?

[goes under]

Danna Harman (narration): Lady Balfour is actually an aristocrat in her own right. Her father was the 17th Duke of Norfolk, but that’s a whole other story. Back to the current Lord Balfour. His full name is Roderick Francis Arthur Balfour, he’s the 5th Earl of Balfour.

Roddy Balfour: The Israeli embassy never ever gets my title right on the invitation.

Danna Harman: That’s ironic. [Roddy laughs]. Really? What do they write?

Roddy Balfour: All sort of things!

Danna Harman: Really? Like?

Roddy Balfour: The Earl Rodrick Balfour, Lord Rodrick Francis Arthur Balfour. I mean things like that.

Danna Harman (narration): We complete our bathroom tour.

Roddy Balfour: That is the Duke of Argyll, and his sister was my great grandmother.

Danna Harman: Hmmm…

Danna Harman (narration): And settle on the couch in the living room, surrounded by framed photographs of Lord and Lady Balfour posing with their four glamorous-looking grown up daughters or with other aristocrats and royals.

I ask him what stories all these present day Balfours tell about their famous ancestor, who was in government for twenty-eight years: One of the longest ministerial careers in modern British politics – second only to Winston Churchill.

Roddy Balfour: He inherited a vast amount of land and wealth when his father died very young. He had seven or eight brothers and sisters. They were a highly intellectual family. Arthur himself was no slouch when it came to intellect. He was a very clever man. So he was very comfortable. He was the first Prime Minister to have his own motor car which he liked to drive into Downing Street. He was always helping out the family.

Kinvara Balfour: So in the family, Arthur Balfour is like a superhero. We absolutely love him. We have his portrait on the walls.

Danna Harman (narration): That’s one of said glamorous daughters, Lady Kinvara Clare Rachel Balfour, whom I meet up with later. Kinvara is forty-one, energetic, fun, and was briefly married to a count. Of course.

She’s English, naturally, but now lives in LA where she works as a writer, producer, fashion pundit and sort of “ambassador of cool.”

Kinvara Balfour: I’d love to sit with him and say like, “why didn’t you get married?” and “what love affairs did you have?” and “who loved you?”

Danna Harman (narration): She’s back in rainy England for a visit and I catch up with her at her fancy private fitness club, right before pilates class. Her blond hair is pulled back, and she’s sipping an energy drink. In the background you might be able to hear another member having his afternoon tea.

It’s fair to say that neither Kinvara nor her father grew up thinking too much about their ancestor’s role in the creation of the State of Israel, or for that matter, about the state of Israel at all.

Roddy Balfour: British children don’t learn about the Balfour Declaration.

Danna Harman (narration): Neither of them have ever seen the actual document.

Kinvara Balfour: So is the actual Balfour Declaration in the British Library?

Danna Harman: I can’t believe you’ve never seen the Balfour Declaration.

Kinvara Balfour: Yeah.

Danna Harman: That’s wild!

Kinvara Balfour: I’ve never known that it was there.

Danna Harman: Lord Balfour, in all fairness, does have a facsimile of the Declaration. He keeps it – where else? – in one of the loos at the Sussex estate.

Despite, shall we say, their slim early interest in the whole thing, there came a point in both Lord Balfour and Kinvara’s lives when they realized that to some people the Balfour Declaration was a super big deal.

In LA, for example, a city all about celebrating its various stars, Kinvara is probably the only one who gets name recognition based on a short document from 1917.

Kinvara Balfour: I’ve made friends with so many Israelis. I’m very celebrated, and they’re all super excited. I say, “yeah, he was my great great uncle and he’s super cool, you know, and great.”

Danna Harman (narration): One time, Kinvara tells me, her last name got her invited to a pretty surreal dinner party at the Beverly Hills Hotel with then President Shimon Peres, who was in town. Her agent – a Jewish guy – called her and said…

Kinvara Balfour: “Balfour? You’re a Balfour, you’re coming for this dinner.” And so I thought, “right. Now I have to do a lot of homework.”

Danna Harman (narration): She quickly reached out to one of her best friends, who, like the agent, is Jewish, for a speed birth-of-a-nation tutorial.

Kinvara Balfour: So that I would do all my Balfour Declaration homework and really get it all up to scratch, should I be sat next to or speak with Mr. Peres.

Danna Harman (narration): She did sit next to him, but lucky for her, the conversation was mostly about Facebook – Peres had just been on a visit to their headquarters. And then there was a mysterious Russian woman at the table who got up and sang ‘Happy Birthday Mr. President,’ even though it wasn’t actually anyone’s birthday. So that took up a lot of attention.

Kinvara Balfour: I didn’t really put my homework to good use because no one really asked me that much about the Balfour Declaration. And then one of his aides kind of got up and said, “Mr. Peres needs to go now.” And that was kind of the end of dinner. And it was just so LA.

Danna Harman (narration): Lord Balfour explains that it’s important to consider his ancestor’s Declaration in its historical context. This is especially the case when it comes to responding to the calls for an apology from the British Government that are being made by certain Palestinian groups.

Roddy Balfour: I find it sort of… I find it very odd.

Danna Harman (narration): He gives me a short history lesson about those historical circumstances.

Roddy Balfour: You know, one of our main concerns was the security of the Suez Canal.

Danna Harman (narration): He mentions…

Roddy Balfour: Colonial priorities, there was the war priority.

Danna Harman (narration): The caveat that…

Roddy Balfour: Oil hadn’t featured quite so much in the Middle East by that stage.

Danna Harman (narration): And of course the fact that so many of Britain’s leaders at the time were religious millenarians, who believed that restoring the Jews to the Holy Land would hasten the Second Coming of Christ.

Roddy Balfour: You know, it has to be remembered that Lloyd George, Balfour, all that generation, they went to church on Sundays – twice often. I went to church twice, every Sunday while I was at school. And I went to chapel every day at school. So what did we hear? We heard the Old Testament, we heard about the Covenant of Abraham, we… we heard about Moses. We read Deuteronomy, Exodus, you know, sang the Psalms of David. I mean, the idea that somehow we didn’t that it was perfectly natural for the Jews to live in Palestine… in fact I think I was brought up sort of assuming that Palestine was already full of Jewish people.

Danna Harman (narration): I try and find out, considering that the first Lord Balfour wrote the famous letter to Lord Rothschild, whether there is a “je ne sais quoi” between the two titled families.

As it happens, the current Lord Balfour, in his capacity as an international tax advisor, actually works for the Rothschilds these days.

Roddy Balfour: I work for them for fifteen years. Evelyn, David, Eric. Terrific people. Terrific.

Danna Harman (narration): But, he insists, they talk tax returns, not Jewish homelands.

Roddy Balfour: Absolutely not, no. And it never really came up.

Danna Harman (narration): That said, there was a Balfour Declaration “where-are-they-now” epilogue of sorts some years back when Lord Balfour found himself on a business trip to Israel on behalf of billionaire financier Sir Evelyn Rothschild. Israel’s then-President Ezer Weizmann – the nephew of Chaim Weizmann – heard that a Balfour was in town and invited him to tea.

It was a lovely historical moment, in a way. But one which was lost, as it turns out, on the security guys at Ben Gurion Airport.

Roddy Balfour: So, I must have been in Israel for forty-eight hours. And in those days, you were grilled far more by the security forces when you left, than when you came into the country. So this guy was giving me a grilling grilling grilling. So I said, “well this is what I’ve been doing,” and I put down my invitation from the President and all the rest of it. He said, “interesting. But what were you doing the other forty-eight hours?” [Danna and Roddy laugh].

Danna Harman (narration): Apparently, I guess, being called Balfour just doesn’t cut it among the Zionists in the way it used to. But just in case someone over there at security is listening, and feels compelled to write Lord Balfour a quick note to smooth things over, I’d recommend addressing him correctly:

Roddy Balfour: If you’re being technically correct, on the envelope, you’d write, “the Right Honorable the Earl Royal of Balfour.”

Act II: And the Lord Came Over with His Car

Tucked away between Nazareth and Afula, in the heart of the Jezreel Valley, Moshav Balfouria feels like a time capsule: Its forty-six agricultural farms haven’t changed much since 1922, when the village was established, and Balfour – its namesake – still looms large. Speaking to some of the Moshav’s old-timers, Zev Levi discovers a quickly vanishing Israel.

Zev Levi (narration): A few hours drive from Israel’s bustling center is the Jezreel Valley. It’s this expansive plain of brown and green agricultural land, bracketed on all sides by tree-lined hills with patches of cement buildings. On our way to the Valley, we passed through Wadi Ara with its hodgepodge of humble homes, impressive mansions, well-known restaurants, and oil-stained auto-repair shops. With the town of Umm al-Fahm towering over us, we watched as an old man on a donkey marched twenty goats across a busy four-lane highway in just a few seconds. It seemed like an impressive feat, but then again, I don’t really know anything about goat-herding. We were on our way to Moshav Balfouria, a small village nestled in the middle of the Valley. Balfouria was one of the first agricultural collectives established in the Land of Israel after the Balfour Declaration and was named in Balfour’s honour. Its forty-six meshakim, or small private farms, have changed very little since it was founded, back in 1922.

Zev Levi: There it is. There’s Balfouria.

Zev Levi (narration): Driving through the yellow sliding gate of Balfouria’s main entrance felt like inching into the past. Everything slowed down, as if we’d stepped into a Meir Shalev novel. By the main roundabout, a giant hand-painted sign read “Balfouria celebrates Shavuot,” a festival that happened four months ago. Under the warm sun, a few oldtimers were busy working in their yards, farming with well-worn hand tools.

Zev Levi: How’s it going?

Yizhar Be’er: Hey!

Zev Levi: Thank you so much.

Zev Levi (narration): Eager to show off the village to us city folk, Amatzia Gilat, one of said oldtimers, immediately launched into a history lesson. Pointing to the gate we had just passed through, he told us about another, more celebrated, visit. Lord Balfour’s. In 1925.

Amatzia Gilat: Lord Balfour came over to visit the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Of course he came to the place called after him.

Zev Levi (narration): Amatzia’s nearly eighty, a proud representative of a dwindling generation who vividly remember the British mandate, the birth of the state, and the War of Independence.

Amatzia Gilat: I was born in Balfouria in 1939. My parents were children of the settlers in Balfouria. So I am a third generation here.

Zev Levi (narration): Amatzia has calloused hands, unruly chest-hair, and a forehead free of wrinkles. He wore aviator sunglasses and a broad smile as he described Balfour’s visit.

Amatzia Gilat: People all over the valley came over here. Jewish and Arabic, you know, Bedouins.

Zev Levi (narration): They all lined the road, mounted on their horses.

Amatzia Gilat: And the Lord came over with his car, passing in the beautiful gate they made. My mother was a child at that time. Seven or eight years. She and another girl brought the flowers to the Lord and they were very excited to be the ones who received the Lord in Balfouria.

Zev Levi (narration): Balfouria is quiet and unpolished, with only a handful of streets, each the width of a single car, all lined with plots of land that are deeper than they are wide. Interspersed with open fields, each property looks like a self-contained Garden of Eden. We visited Amatzia’s neighbor, Yizhar Be’er.

Yizhar Be’er: Each season, it’s own fruit and vegetable. Watermelon, you see. My chicken here.

Zev Levi (narration): Yizhar is a short, well-built man with cropped white hair. He greeted us in an unbuttoned shirt with sleeves rolled up his forearms. He used to be a journalist, but a few years ago he transitioned into a full time farmer. Everything about him – from his firm handshake to the dirt under his fingernails to his smiling chapped lips – suggests that his old desk-job couldn’t be further from his mind.

Yizhar Be’er: My father passed away and he left for his three children this piece of land in Balfouria. And I… I got about ten dunam of empty field. And since then, in the last five years, I make my paradise.

Zev Levi (narration): Yizhar gave us a tour of his paradise, which is just about the size of two football fields put together.

Yizhar Be’er: In few weeks, I will harvest the olives and we will make oil and olives to eat. I start growing up bees. I have honey.

Amatzia Gilat: Yeah, you grow everything!

Zev Levi (narration): While commending Yizhar’s bounty, Amatzia noticed that the only thing he lacked was cows.

Amatzia Gilat: I see that poultry and, only cows; you miss cows. You have to bring a cow or two.

Zev Levi (narration): Yizhar disagreed.

Yizhar Be’er: Cows? No, I want to be more independent.

Zev Levi (narration): After a glass of homemade lemonade and some biscuits, Amatzia suggested that we all drive around the village.

Amatzia Gilat: You see, all the black fields are prepared for the winter – for wheat or whatever other winter crops. You can see also olives orchard over there and the almonds over there.

Zev Levi (narration): We turned up a small hill.

Amatzia Gilat: You see this almond orchard, in a month or two, the leaves will fall down.

Zev Levi (narration): Near the top of the hill, Amatzia pulled over outside a big black iron gate, adorned with a large golden Magen David. Balfouria’s cemetery.

Amatzia Gilat: Please, come in. Follow me. You know, maybe you are afraid… [laughs]. We are in the Balfouria cemetery. The first person died here on 1926, it was an old lady. Since then, all the veterans are buried here. Second generation, third generation, we have here some of our young who fell in Israel wars.

Zev Levi: Will you be buried here one day?

Amatzia Gilat: Maybe [laughs].

Zev Levi: Would it bring you pleasure to be buried in Balfouria?

Amatzia Gilat: I don’t know what will be my pleasure after I’m dead [laughs]. But anyhow, I think and I hope that I can be buried here, with my ancestors. A part of our history. Only people who were or lived here can be buried here. It’s quite a right to be buried here.

Zev Levi (narration): Amatzia personally knew almost everyone interred in this cemetery. He has childhood memories of the moshav’s founders; tough, hard-working idealists like his grandfather, who was Balfouria’s first blacksmith.

Amatzia Gilat: My grandparents are here. All the stones here you see, are of the first settlers of Balfouria. Here is my grandfather. You can see, this stone.

Zev Levi: Amatzia, how does it feel for you to visit this place?Amatzia Gilat: Well it’s quite a feeling. I feel as, you know, as you have roots in the ground, and you feel them. And the roots starting from here.

Zev Levi (narration): On the way back from the graveyard, we passed a single row of cypress trees next to a large dirt field. The field looked completely ordinary, but it used to be a magical site that brought real life superstars to the village. Here’s Yizhar again.

Yizhar Be’er: Many Israelis didn’t hear about Balfouria and didn’t know where it is, because Balfouria was not in the headlines during the last hundred years, except in one issue.

Zev Levi (narration): So what’s Balfouria’s claim to fame? Their soccer team. Their soccer team from six decades ago, that is.

Yizhar Be’er: That arrived to the national level.

Amatzia Gilat: And this was the place where they had the ground to play.

Zev Levi (narration): Amatzia pointed to the unimpressive patch of mulched earth. Behind his sunglasses and stiff upper lip, he seemed to reach all the way back to when he was just a boy, living in a very different Israel. An Israel where national-league soccer players lived and worked alongside the rest of the village folk; they didn’t make millions or date supermodels. In that Israel, a national-league soccer game was a village-wide affair.

Amatzia Gilat: First of all, it was a celebration. All the people came over with chairs from home because there was no place to sit here. We don’t have a stadium over here. And then, it was quite a pride. You see we were a very small place. And we held a very very good team, who played in the first league.

Zev Levi (narration): The team, Ha’poel Balfouria, had just one weakness…

Yizhar Be’er: The team, was well known as the worst defence team in football. There was a game, with I think Ha’poel Ramat Gan, they lose 11-0.

Zev Levi (narration): Actually, the game Yizhar is referring to was against Maccabi Tel Aviv. And the score? It was 12-0.

Yizhar Be’er: Why? The team never practice. They came to the game directly from the cows and the sheep and the fields.

Zev Levi (narration): Even though the team spent only two years in the top division, and was ranked last both times, and those two years were in the 1950s, the fact that they made the national stage at all is still a great source of pride.

Amatzia Gilat: We liked our team, our players. They were us.

Zev Levi (narration): In a flash, a tractor punctured Amatzia’s reverie. The boy from the 1950s was gone and the cheering fans morphed into a handful of workers toiling on the land.

Amatzia Gilat: Nowadays, you see, it’s a field. In the near future, they will build houses all over here.

Zev Levi (narration): On the way back from the remains of the once glorious soccer pitch, we again passed by the moshav’s main gate.

Yizhar Be’er: Look, here is… Stop a minute. Balfour and his group came from the junction over there, came over here, and then, if you see the green gate, the first floor was built specifically to the visit of Balfour.

Zev Levi (narration): I stared at the junction in wonder, trying to imagine what it would be like if, every time you passed by your front gate, you were transported a century back in time. How would that feel?

Amatzia Gilat: I feel that I live as part of history. You know? It is not just a place to live.

Zev Levi (narration): That’s Balfouria; Not just a place to live.

Act III: What’s in a Name?

In April 1948, a few weeks before the establishment of the State of Israel, Ezra and Saida Chakak, a Jewish couple from Baghdad, gave birth to identical twin boys. A zealous Zionist, the dad decided that this was excellent opportunity to honor the movement’s towering figures. Almost seventy years later, Hannah Barg meets up with the twins, and finds out what it’s like to live your life as a walking symbol.

Hannah Barg (narration): When I visited the Chakak brothers in Kiriyat Moshe, a religious neighborhood on the edge of Jerusalem, they greeted me in matching outfits — black pants, a simple white button down, and the exact same reading glasses hanging around their necks. The two sixty-nine year old men had matching smiles and matching wrinkles around their eyes. And while I could spot a few differences in their aging features – one had more hair, the other a rounder face – they were unquestionably identical. The kind of twins that can’t help but interrupt each other and finish each other’s sentences. The dining room table was filled with objects they’d taken out for me to see — there were family photo albums, poetry books, the colorful striped gowns their mother sewed for them as babies, handmade childhood toys. The Chakak brothers, you see, are collectors. Of stories, of memories, and of history itself. Partly, that’s just who they are, but it’s also thanks to their dad, who thrust the weight of history upon them from the very start.

Herzel Chakak: Our names were leading the way.

Hannah Barg (narration): Without further ado, here are the twins.

Herzel Chakak: Hi I’m Herzel Chakak.

Balfour Chakak: I’m Balfour Chakak.

Hannah Barg (narration): Yeah, Herzel and Balfour, as in, the two legendary champions of Zionism you read about in history books. Only, this Herzel and this Balfour were born in 1948 to Jewish parents in Baghdad, just a couple of weeks before the establishment the State of Israel. Their birth was something of a legend itself, at least in their family. Here’s Herzel:

Herzel Chakak: The midwife she came, she took me out, but she didn’t know there was another one.

Hannah Barg (narration): Keep in mind this was a homebirth. In 1948. No heart monitor or anything. So after the midwife delivered Herzel, she went on her way.

Herzel Chakak: After an hour and a quarter, she came again when they called her, and Balfour came to say his declaration.

Hannah Barg (narration): Their miraculous birth brought comfort to a grieving family. Seven years earlier, in 1941, their mother’s two brothers were killed in the Farhud – a massacre against the Jews of Baghdad. In a way, she thought of her beautiful boys, Herzel and Balfour, as a compensation for her loss. After their birth a rabbi told the family, “you received two for two.” So maybe you’re wondering how identical twins born in Baghdad ended up being named for two prominent European statesmen? Balfour explains.

Balfour Chakak: My father was a activist in the Zionist underground in Baghdad.

Hannah Barg (narration): And when his twins were born, he knew he wanted to pay tribute to the Zionist movement’s towering figures.

Balfour Chakak: Since we were born, we were walking symbols. Our names were Herzl and Balfour. So it was something symbolic of redemption, of independence.

Hannah Barg (narration): And had they been triplets…

Balfour Chakak: If he had three sons, it was Herzl, Balfour and Weizmann. But he has only two, so he has to choose.

Hannah Barg (narration): Two years after the twins were born, the Chakak family was in trouble. Someone had squealed on Ezra, the father, to the Iraqi police, saying that he was donating money to Keren Kayemet, the Jewish National Fund. He spent three months in jail, before paying off one of the guards.

Balfour Chakak: He was released near leil ha’seder in 1950. At the night, after the Passover Seder, our family escaped from Iraq, Baghdad to Tehran. We were taken to a secret camp of the Zionist Movement, in cemetery in Tehran, we were also two years old we were.

Hannah Barg (narration): That’s right, the Jewish Agency’s transit camp was in a cemetery…

Herzel Chakak: It’s called “beheshtia.”

Balfour Chakak: It means paradise, gan eden. Beheshti is cemetery, called beheshtia, Paradise.

Hannah Barg (narration): And one called paradise, no less.

Balfour Chakak: So we were three weeks in the paradise, in cemetery as little kids. And they tied to our legs “djnijel” – bells – to frighten all the bad magic powers.

Hannah Barg (narration): After three weeks, the Chakak family left the cemetery and boarded an airplane to Cyprus. From Cyprus they were taken to Israel, where they lived in a ma’abara, a transit camp. Eventually they settled in Jerusalem. Here’s Herzel:

Herzel Chakak: It was something special to be twins in Jerusalem because they didn’t know who is who. So if I went to the barber and Balfour came after one day or two days. He says, your hair is…

Balfour Chakak: He say, “how your hair is grow? In a day!” [laughter].

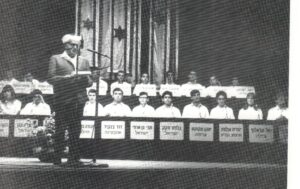

Hannah Barg (narration): No one could tell them apart. Actually, the only way people could tell which brother was named for the Zionist leader and which one was named for the British politician was to look down at their wrists. Balfour wore his watch on his left hand, and Herzel – thankfully – wore his on his right. They were excellent students, and had photographic memories. Before long, they were both accepted into Jerusalem’s most elite high school, where there was just a handful of other Mizrahi immigrant kids. The Chakak brothers gradually became minor celebrities around town, but that was nothing compared to the national fame they attained in the spring of 1965, when they turned seventeen. That’s when Herzel and Balfour participated in the second International Bible Competition. You may remember the International Bible Competition from one of our previous episodes. If you don’t, all you need to know is that this competition is a big deal. And in 1965? It was an even bigger deal. Herzel and Balfour immediately stood out. While they came from a traditional home, they weren’t religious like most of the other competitors. But in the preliminary rounds they were heads and shoulders above everyone else. In the Jerusalem-wide competition, Herzel won first place and Balfour was the runner up. And in the national round, they once again came out on top, together with Hagi Ben-Artzi, who, incidentally, is Sarah Netanyahu’s older brother. In any event, this meant that the Chakak brothers were among the three teenagers who represented Israel in the final stage, the International Competition, on Yom Ha’Atzmaut, Independence Day, 1965. The auditorium in Jerusalem was packed with twenty-two Bible whizzes from twelve different countries. Proud family members and eager journalists filled the hall. Everyone stood up as trumpeters announced the entrance of the Prime Minister, Levi Eshkol, along with Yitzhak Rabin, the Chief of Staff, and other dignitaries like Abba Eban and David Ben-Gurion. Pumped full of adrenaline, the Chakak twins were ready to go. They both reached the final round, when just three contenders were left standing. Balfour, Herzel, and the US champ, Esther Rose Freilich from Far Rockaway, Queens. Balfour had an almost perfect score, and Esther was far behind. But Herzel – in second place going into the last stretch – could still theoretically catch up to his brother and win it all. And that’s when, at least this is what Herzel claims, a delightful backstage distraction thwarted his would-be comeback.

Herzel Chakak: Balfour was on the stage, and I went to the isolated room with an American, she was the champion of America and Diaspora. And to be with someone gingit [laugh]…

Herzel Chakak: Redhead… you forget all the Bible! So I lost and he wins.

Hannah Barg (narration): The redhead from America, he says, made him forget all his Bible verses. Balfour was crowned the champ, Herzel was the silver medalist. Esther, with her powerful ginger locks, went back to New York, where she later became a math professor and, believe it or not, the mother of eight. The first and second place finishes of the identical, memorably-named twins from Jerusalem plunged them into Israeli stardom. They were invited down to Sde Boker, to meet with Ben-Gurion, and to the President’s house in Jerusalem, for an audience with Zalman Shazar. And basically ever since, Herzel and Balfour have continued to thrive. Both went on to become respected poets, each serving three terms as Chairman of the Hebrew Writers Association.

Balfour Chakak: It’s a unique phenomenon that two identical twins are writing poems. We didn’t find in other country two identical twins that are both poets and writers.

Herzel Chakak: We are doing everything together.

Balfour Chakak: He is my editor and I am his editor. When we talk to each other, sometimes I can feel that I’m talking to myself. Because it’s one person that’s divided to two persons.

Hannah Barg (narrator): They both married Ashkenazi women – Balfour’s wife is Polish and Herzel’s is Russian – and they had children, many of whom became ultra orthodox. And throughout it all, the weight of their birth names guided their way.

Balfour Chakak: It’s right, we fulfilled the dreams of our parents. They dreamed that they will have Zionist sons, and we fulfilled their dreams. They were satisfied.

Hannah Barg (narration): To continue what his father had started, Balfour decided his marriage should pay tribute to his namesake. He convinced his fiance to share their wedding anniversary with the anniversary of the Balfour Declaration.

Balfour Chakak: I made my wedding in the second of November and Herzl was jealous so he made his wedding in the day of Jabotinsky.

Hannah Barg (narration): Even as they approach seventy, Herzel and Balfour Chakak remind me of childhood twins who want to be both better than and exactly like each other. They see each other almost every day, and when they don’t, they talk on the phone. Their wives listen in on these conversations simply to know what their husbands are up to. Theodore Herzl and Lord Arthur James Balfour could not have imagined the Iraqi-born twins who came of age with the State of Israel. The Chakaks are proud Zionists who have made history, in their own small way. And till this very day, the only discernible difference is the hand on which each wears his watch.

Act IV: Not Your Typical Landlady

When David Harman was eighteen-years-old, he returned to Israel to enlist in the IDF. Since the rest of his family was stationed abroad, he needed to find a place to rent. Lucky for him, a chance meeting with Golda Meir in Jerusalem’s Rehavia neighborhood landed him not only a room on Balfour Street, but also an opportunity to witness history in the making.

Mishy Harman (narration): These days, when most Israelis hear the name ‘Balfour’ they don’t think of good old Arthur James, his phenomenal facial hair or his philosemitic Declaration. Instead, the first association that comes to mind is a street. A street in Jerusalem. Balfour Street. And what’s so special about that street? Well, a lot of things really, but probably nothing more than the identity of the resident living at number three. The Prime Minister. That’s right, America has Pennsylvania Avenue, the Brits have Downing Street and we, we’ve got Balfour.

Mishy Harman: Abba, do you think that there’s some symbolism in the fact that the Prime Minister of Israel lives on Balfour Street?

David Harman: Yeah, you can… You can impute symbolism to anything. If you want to think it’s a symbolic thing, OK. But this Prime Minister’s building is now by decision of the government gonna be moved. There goes your symbolism.

Mishy Harman: You know that it’s Bibi’s birthday today.

David Harman: Mazel tov!

Mishy Harman (narration): I asked my dad, David, to meet me on Balfour Street.

David Harman: OK, what we gonna do? We’re gonna walk here?

Mishy Harman (narration): This was, after all, where he grew up.

David Harman: Yeah, our home was right down this street to the left, on Disraeli Street, a street named for another British Prime Minister.

Mishy Harman: So would you come here a lot when you were a kid?

David Harman: Yeah, I walked up and down here all the time. I walked on this still at least once or twice a day ‘cuz this was the route that you took from our apartment into the center of town.

Mishy Harman (narration): We set out on a little stroll down memory lane.

David Harman: Yeah, well, this building right here to our right, there were a number of very important people who lived in that building. The one who lived on the first floor was Prof. Michaelson, who was my opthamologist and prescribed my first glasses when I was nine years old. And on the top floor lived Moshe Sharett, who was Israel’s second Prime Minister, it was his private apartment.

Mishy Harman: It’s not a particularly fancy building or anything. It’s just an apartment building.

David Harman: It’s an apartment building. A walk-up in fact. Sharett walked up two flights. In this building, also lived Zalman and Rachel Shazar. Zalman Shazar became Israel’s third President.

Mishy Harman: Why did all these people live on this one street?

David Harman: Well, it was walking distance from where they worked, the Prime Minister’s office.

Mishy Harman (narration): Just sit with that for a second. The reason all these founding fathers and mothers of the State lived here, in modest apartment buildings, was because they could walk to work. No limos, no motorcades, just feet. There were also other houses on Balfour Street, older, single family houses.

David Harman: Like the one right here to our right, which is where our very close friend Walter Eytan lived.

Mishy Harman: So these were Arab buildings originally, that were left, or forced to leave in ‘48?

David Harman: I believe so.

Mishy Harman: And then they were basically annexed by Jews?

David Harman: Yes. And this building over here, which is a brand new building (brand new… it was built in the 50s), was where a classmate of mine, Nira Bar-Akivah, lived and we used to have class get-togethers there. Yeah, and across the street in this building, lived Amir Schor, another classmate of mine. And Amir and Nira ultimately got married.

Mishy Harman: These two classmates that lived across the street from each other?

David Harman: Yeah, but they were not going together when we were kids. Now I think it was this building, if I’m not mistaken… [goes under].

Mishy Harman (narration): My dad had stories about each and every house. One was where Alex Kainan used to live.

David Harman: Alex was a professor at the Hebrew University, a friend of the family’s.

Mishy Harman (narration): Another was the home of Yitzhak Nissim.

David Harman: The Sephardic Chief Rabbi.

Mishy Harman (narration): My dad told me tale after wonderful tale of Jerusalem in the 1950s, but none of them captivated my imagination as much as the story about when he, and an unusual roommate, shared the big old house on the corner of Balfour and Smolenskin.

David Harman: Mishy, I’ve told you the story six times. It’s recorded ten times. Again you want me to tell you?

Mishy Harman: Yeah, again.

David Harman: In May of 1962…

Mishy Harman (narration): My dad – who was then eighteen – came back to Israel, in order to go into the army. He had been living with his family in Washington D.C. for a few years, since his dad, Abe, was serving as an Israeli diplomat there. My father was going to be what’s called a Chayal Boded, a lone soldier whose family doesn’t reside in the country, and he needed to find a place to live. So a week or two before he was supposed to go into the army my dad and his dad came to Israel (it was quite a trip back then), to go apartment searching. And that’s how, on a warm day of early summer, they found themselves trekking up Gaza Street, in Jerusalem’s Rehavia neighborhood.

David Harman: Checking out a few places which I could rent. And as we were walking, a car (a pretty fancy car by the standards of those days) stopped and the window rolled down and an elderly lady poked out her head and said, “Abe and David what are you doing here?”

Mishy Harman (narration): The elderly lady in question…

David Harman: It was Golda Meir, who was then the Foreign Minister, my father’s boss, and an old time family friend.

Mishy Harman (narration): Jerusalem was a small town in those days. A place where it made sense that you’d bump into the Foreign Minister and start chit-chatting. In any event, they told Golda they were looking for a room for my dad, who was about to go into the army.

David Harman: And she immediately said “stop looking, I live in a house, a block and a half away from here, which is all empty, and it would be a pleasure if you just came and took a room there. And two days later I moved in.

Mishy Harman: What did you think when she said “come live with me”?

David Harman: I was delighted! It was a good address, great location, low rent.

Mishy Harman: So Golda was your first roommate?

David Harman: She was not my roommate, we were housemates. I was her boarder.

Mishy Harman (narration): Golda was then living in the Foreign Minister’s official residence, at number three Balfour Street, which later on became the Prime Minister’s house.

Mishy Harman: What was it like living with Golda?

David Harman: Well, firstly, Golda was a very warm and wonderful person. And I must say somewhat lonely. I mean she was this important woman and she would come home usually late in the evening, to ummm… usually an empty house.

Mishy Harman (narration): On a typical night, my dad recalls, she would swing by his room, and very softly say…

David Harman: “David? Ata Sham?”

Mishy Harman (narration): “Are you there?”

David Harman: And I would come down, and we would sit and have tea. And she would take a sugar cube and break it in the palm of her hand and put one half in each cheek and that’s how she drank her tea. And she drank her tea and smoked. She smoked unfiltered Chesterfield cigarettes. And we would sit around the table in the famous kitchen, ‘Golda’s Kitchen,’ and spend hours discussing this, that and the other.

Mishy Harman (narration): Now, living with the Foreign Minister wasn’t exactly the most normal way to spend your military service.

David Harman: I was in a unit where we were told – and I kept to it assiduously – not to say anything about what we’re doing. (It was an intelligence unit). So when she asked me what I was doing in the army I would say, “I’m sorry, I can’t tell you.” She said, “you can tell me. [David laughs] It’s OK.”

Mishy Harman (narration): My dad lived with Golda Meir for close to four years, and still talks about her – and that period – with a mixture of nostalgia and admiration.

David Harman: As far as I was concerned, in addition to having a good friend, and a very warm sort of mother figure… Ummm, once I had a toothache and Golda prepared some grandma’s remedy for me with salt which she fried and then put in a handkerchief and then I put it on my cheek and ummm… (It didn’t help, mind you). But beyond that, thinking back, I basically had a front row seat during a critical period of this country’s development, seeing the workings of government, and to just be a fly on the wall while all this was going on is one of the most significant experiences of my life.

Mishy Harman (narration): Today Bibi and Sarah live in that grand old house, and things are a bit less village-like than the days in which my dad and Golda would go grocery shopping together, or catch the late night showing at the Eden cinema downtown. There’s a tall wall surrounding the house, and severe looking Shabakniks don’t let you get close. The entire block is now closed off, and we had to get special permission just to stand there and talk.

David Harman: I told them that I was just coming through to record some memories with my son, and they said ‘OK, just don’t take pictures.’ This was totally open when I was a kid. None of these cameras were here, nothing. And there were two elderly policemen at the front entrance, and this was not considered a heavy-duty job for policemen.

Mishy Harman (narration): As we walked back to the car at the end of our little walking tour, my dad noticed a sign in one of the windows.

David Harman: Oh, that apartment’s for sale, my G-d, ha! Sharett’s apartment.

Mishy Harman: You interested?

David Harman: No.

Mishy Harman: You wouldn’t want to live on Balfour Street?

David Harman: Ahhhh… Location is good. Well this was a great pleasure.

Mishy Harman: Thank you, Abba. That was fun!

David Harman: Yeah. Don’t use a lot of it.

Mishy Harman: What do you mean?

David Harman: How much are you going to use of this?

Mishy Harman: All of it!

David Harman: You are not!

Mishy Harman: Ha?

David Harman: You are not!

Mishy Harman: Tov, yalla.

David Harman: Yalla chamud.

Mishy Harman: Bye.

[Kiss]

David Harman: See you later.

Credits

The original music in this episode was composed and performed by Ari Jacob, with additional scoring by Yochai Maital. The episode also includes tracks by the late Nachum Heiman. The final song, “Balfour“, is by Itay Pearl. The episode was edited by Julie Subrin, recorded by Shelly Dardik and Raphael Biberfeld and mixed by Sela Waisblum.

Thanks to Shir Shimoni, Josh Berger, Simon Wilkinson, Nave Yehezkely, Yisrael Sivan, Izi Mann, Elan Ezrachi, Naomi Schneider, Rotem Zin, Oren Harman, Esther Werdiger and Wayne Hoffman.

Sponsors

Best-Day Adventures offer specialized trips for active Jewish singles in their 40s, 50s and 60s. They plan their trips to a tee, with top-notch services, fun icebreakers, and an indulgence of enriching discoveries designed to create a warm, welcoming environment.

Best-Day Adventures offer specialized trips for active Jewish singles in their 40s, 50s and 60s. They plan their trips to a tee, with top-notch services, fun icebreakers, and an indulgence of enriching discoveries designed to create a warm, welcoming environment.

Wartime Diaries

Wartime Diaries