David Remez was born as Moshe David Drabkin in what is today Belarus, in 1886. As a boy he studied Talmud with his grandfather and then attended a traditional cheder. In 1905, he was drafted into the Tzar’s army, but was soon dismissed, on the grounds of being an only child. He then moved to Constantinople, Turkey, to study law, and it was there that he met and befriended David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, who would both – years later – ink their names beside his own on the Israeli Declaration of Independence.

Remez moved to Palestine as a newly-married man in 1913 and started working the land in Be’er Tuvya, Karkur and Zichron Yaakov. But his career as a farmer didn’t last long. By 1921, he was already the head of the national construction company, Solel Boneh, and – in that capacity – bought lands and initiated affordable housing projects.

Under the tutelage of Berl Katznelson, he served for almost a decade as the Secretary General of the all-powerful Histadrut Workers’ Union and was instrumental in founding many of its subsidiaries, such as the Zim shipping company, the Mashbir department stores, and the still-thriving Am Oved publishing house. In 1945, he was elected to be the chairman of the Va’ad HaLeumi, the Jewish National Council, and though – according to certain historical accounts – he voted against Ben-Gurion’s proposal to declare the State on May 14, 1948, he nevertheless proudly signed the Declaration, and was named the country’s first Minister of Transportation.

He was a lover of the Hebrew language, and coined many new words, such as muvtal (unemployed), vetek (seniority), tachbura (transportation), mimtza (archeological finding) and dachpur (bulldozer).

In 1951, while serving as the Minister of Education and Culture, Remez died at the age of sixty-four, making him the first of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence to pass away. At a Mapai Party memorial meeting, future Prime Minister Moshe Sharett praised his linguistic skills and unparalleled succinctness. “He walked in his secular life,” Sharett said in his eulogy, “like a priest through the temple of language.”

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: There were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

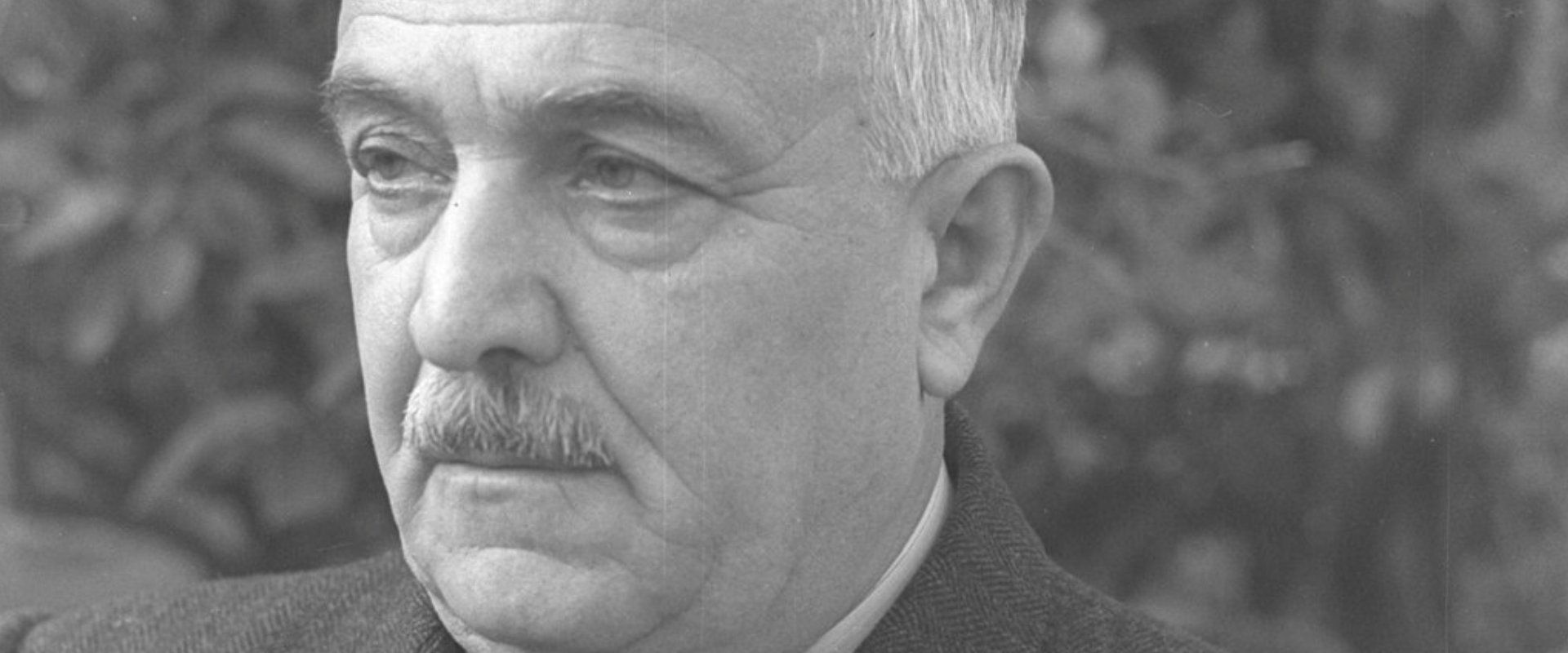

Today we’ll meet David Remez, and his grandson, Gideon Remez. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

Act TranscriptGideon Remez: He liked the mishkal segolim, the ‘eh-eh,’ the combination, like ‘Remez.’ And he even incorporated the name Remez into one of the words, which you probably are familiar with, but you don’t know (as no one else does), that he coined the term ‘ramzor’ for traffic light. Remez-or – a light signal.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Gideon Remez, a Sokolov Prize-winning journalist who headed Kol Yisrael, or the Voice of Israel’s, foreign desk for decades. His grandfather, David Remez, Israel’s first Minister of Transportation and the man who chose the biblical phrase ‘El-Al’ as the name for Israel’s national airline, was known for his linguistic flair, for his love of organized labor and – of course – for his oversized autograph.

[Signed, Sealed, Delivered? introduction]

Today we’ll meet David Remez, and his grandson, Gideon Remez. He’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series. Here’s our producer Mitch Ginsburg with Gideon Remez, David Remez’s grandson.

Mitch Ginsburg (narration): David Remez, who – among many other things – invented the Hebrew word for “archaeological finding” while sitting in a British prison cell, was born as Moshe David Drabkin, in 1886, in what is today Belarus.

He studied Talmud with his grandfather, a rabbi, and in his youth attended a traditional cheder. In 1905, he was drafted into the Tzar’s army, but was soon dismissed, on the grounds of being an only child. He moved to Constantinople, Turkey, to study law, and it was there that he met and befriended David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, who would both – years later – ink their names beside his own on the Israeli Declaration of Independence.

Remez moved to Palestine as a newly-married man in 1913 and started working the land in Be’er Tuvia, Karkur and Zichron Yaakov. But his career as a farmer didn’t last long. By 1921, he was the head of the national construction company, Solel Boneh, and – in that capacity – bought lands and initiated affordable housing projects. Under the tutelage of Berl Katznelson, he served for almost a decade as the Secretary General of the all-powerful Histadrut Workers’ Union and was instrumental in founding many of its subsidiaries, such as the Zim shipping company, the Mashbir department stores, and the still-thriving Am Oved publishing house. In 1945, he was elected to be the chairman of the Va’ad HaLeumi, the Jewish National Council, and though – according to certain historical accounts – he voted against Ben-Gurion’s proposal to declare the State on May 14, 1948, he nevertheless proudly signed the Declaration, and was named the country’s first Minister of Transportation – or tachbura – which, by the way, was another word he himself invented.

As the Minister of Transportation, he officially opened Ben-Gurion Airport (which was then called the Lod Airport) and – on August 7, 1949 – he was the guest of honor aboard Israel Rail’s maiden trip from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Not long afterwards, he made the very first phone call to the southern city of Eilat, speaking over a somewhat crackly line to Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion.

He was a lover of the Hebrew language, and coined many new words, such as muvtal (unemployed), vetek (seniority) and dachpur (bulldozer).

In his personal life, Remez was said to have had a long-standing love affair with Golda Meir – a rumor that some say was confirmed in 2008 with the publication of their private correspondence. In an interview at the time, Remez’ grandson Gideon called the affair “the most guarded, and yet most well-known, state secret.”

In 1951, while serving as the Minister of Education and Culture, David Remez died, rather suddenly. He was sixty-four-years-old, and the first of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence to pass away. At a Mapai Party memorial meeting, future Prime Minister Moshe Sharett praised his linguistic skills and unparalleled succinctness. “He walked in his secular life,” Sharett said in his eulogy, “like a priest through the temple of language.”

Here’s Remez in a May 1951 speech, just several weeks before his death:

David Remez: Gentlemen, it is not my manner to speak at length. I always stand with great awe in our houses of Torah study and our houses of science. I know that there within lies the secret of our strength to stand on our feet and take our place in the world. I always set before me the verse, “the Lord did not set his love upon us, nor choose us, because we were greater in number than other peoples; for we were the smallest of all peoples.” So if not in numbers, what is the source of our strength? One of the wonderful treasures that is archived in our national psyche is our strength in Torah, our strength in science, and our strength in knowledge.

Gideon Remez: The John Hancock on the Israeli Declaration of Independence in terms of size is Ben Gurion’s. But my grandfather’s is the one that stands out most if you look at it from a distance, because he used a very thick fountain pen, so it’s the darkest one, and also the only one that’s vowelized in Hebrew. He had a special attachment to the name because it wasn’t his. He was born Moshe David Drabkin in 1886. And he adopted my grandmother’s maiden name, Remez, when they married, perhaps because it sounded more Hebrew than Drabkin. He was one of a group that went to study law in Istanbul. He went back to Russia, married my grandmother, and they came to then-Ottoman Palestine in 1913. Here he became gradually, after being a simple laborer for several years, he began to rise in the Labor Movement, and he then participated in the establishment of the Histadrut on Hanukkah of 1920. My grandfather was known as a conciliator and mediator among the various factions within the yishuv. In June of 1946, on the Black Saturday, Shabbat HaSchora, he was arrested by the British along with other members of the leadership of the yishuv and he was held in Latrun. His roommate there — or cellmate — was Yitzhak Gruenbaum, the former Jewish leader from Poland. And Gruenbaum wrote that one day his socialist Labor leader roommate said to him, “I want to see whether I still remember how to read the Talmud.” So he went down to the regular camp and joined some of the prisoners from the Irgun (Etzel) and from Lehi, what the British called the Stern Gang, and came back later and told Gruenbaum happily, “I can still read the Talmud.” And from then on whenever there was any negotiation between these factions and the mainstream Labor-led leadership, the right wingers, Revisionists, insisted that Remez represent the leadership because he was known to be capable of at least bringing people together and hammering out some kind of agreement. He was known for his wit and his puns. In particular, he had the gift of brevity. Some of his best known speeches were one sentence long. On the day that the first Knesset was opened, he handed over the baton with a one sentence speech saying, [in Hebrew] “As the river flows into the sea, so Knesset Israel flows into Medinat Israel, which will live forever.” “As the river flows into the sea, so Knesset Israel,” as it was known then, “flows into Medinat Israel, which will live forever.” He was Minister of Transportation. And at that time, transportation included the post office, and he was in charge of reactivating the post office from the British Mandate. And until very close to the Declaration itself, the name of the State hadn’t been determined. How do you print postage stamps when you don’t have the name of the country? So proofs were made with names like Yehuda and a couple of others, and he finally determined to print up the first Israeli stamps, which don’t say Israel, they say Doar Ivri — Hebrew Post — they are the most valuable for collectors today. Not only my grandfather, my father commanded the Air Force in the War of Independence after flying a Spitfire for the RAF in World War II. My mother was one of the early American olim, arrived here in 1945 pregnant with me. So yes, I do feel that I have a founding share in the country. It doesn’t entitle me to any privilege, but it does enhance my commitment to the country. Definitely. My father was sent to the United States in 1951. He went first and I and my mother followed. I was just over four-years-old. It was around Hanukkah, and El Al airliners didn’t have the range then to fly nonstop to the United States so there were stopovers in Athens, Rome and London. And when I heard that we were about to land in Greece, I said, “no way. The Greeks are our enemies (this is Hanukkah), I’m not landing in Greece.” My grandfather went and bought me a pop gun, like the one Christopher Robin uses to shoot down Winnie-the-Pooh’s balloon, and says, “well here, if the Greeks try any monkey business, you can defend yourself.” You know, the cartoonist Dosh had a strip for Hanukkah, I think in the 50s, or early 60s. You see little Israel with the tembel hat — his image of the Israeli — talking with the ghost of Yehuda HaMacabi, Judas Maccabeus, in the cloud, complaining that this is bad and that is bad, and even our democracy is in danger.” And Yehuda HaMacabi says, “democracy?! Now I understand all your troubles, you’re Hellenized!” So our democracy is in trouble. I’m not leaving this country no matter what happens. But it makes me feel sorry to see what the country has come to now. I think that sometimes we put things in the wrong proportion. To give one example, there’s nothing wrong at all with what they call the Abraham Accords. But from our point of view, having a friendly relationship with Bahrain, it’s fine, it’s OK. But it’s not going to solve our problem with the Palestinians. We have to find an accommodation with our neighbors. It’s not going to solve itself. If we have a one-state situation, then the choice will be between ultimately losing the Jewish majority, or justifying the accusations that we’re an apartheid state. I don’t see any other choice. My grandfather was a committed social democrat. He believed in the public sector. He was one of the originators of the cooperative ideal in Israel, setting up cooperatives from transportation through printing to consumerism. Now they’ve all been taken over by private interests. He would be devastated to see the income gap between rich and poor in Israel today. Anything reeking of socialism or social democracy has become practically taboo since the prostituted, tyrannized version of it in the Soviet Union failed. It has been replaced by a complete dedication to a kind of ultra-Thatcherite economy that I don’t think is doing the country that much good either. When he took over as Minister of Education in the second cabinet, which was his last post (he died in office), he penned in his handwriting a greeting to elementary school pupils, saying, [in Hebrew] “redeemed boys and girls,” which means in English roughly “redeemed, or liberated, boys and girls, greetings from the Government of Israel. Study hard, work hard. The future is yours. Build the country, build the nation.”

For an account of the famous May 12, 1948 cabinet meeting in which it was decided to declare statehood, see historian Morechai Naor’s Haaretz article.

For a recording of Remez (and fellow Declaration of Independence signatory Aharon Zisling) speaking at the first Histadrut Workers’ Union meeting following the founding of the State, listen to this recording.

For clips of the maiden Israel Rail voyage from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, see this archival video.

For a four-minute recording of the first phone call from Eilat, listen to this audio clip.

For David Remez’ many contributions to the Hebrew language, see this fascinating article (in Hebrew).

For Remez’ obituary, see the May 20th, 1951 front page of Davar.

For Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett’s speech at the Mapai Party meeting which took place one week after Remez’s passing see the Ben-Yehuda Project.

For a discussion of the ethics of exposing the love affair between Remez and Golda Meir, see this Seventh Eye article.

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubber is Leon Feldman.

The end song is HaIvrit HaChadasha (lyrics and music – Omri Glickman, arrangement – Piloni), performed by HaTikvah 6.

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.