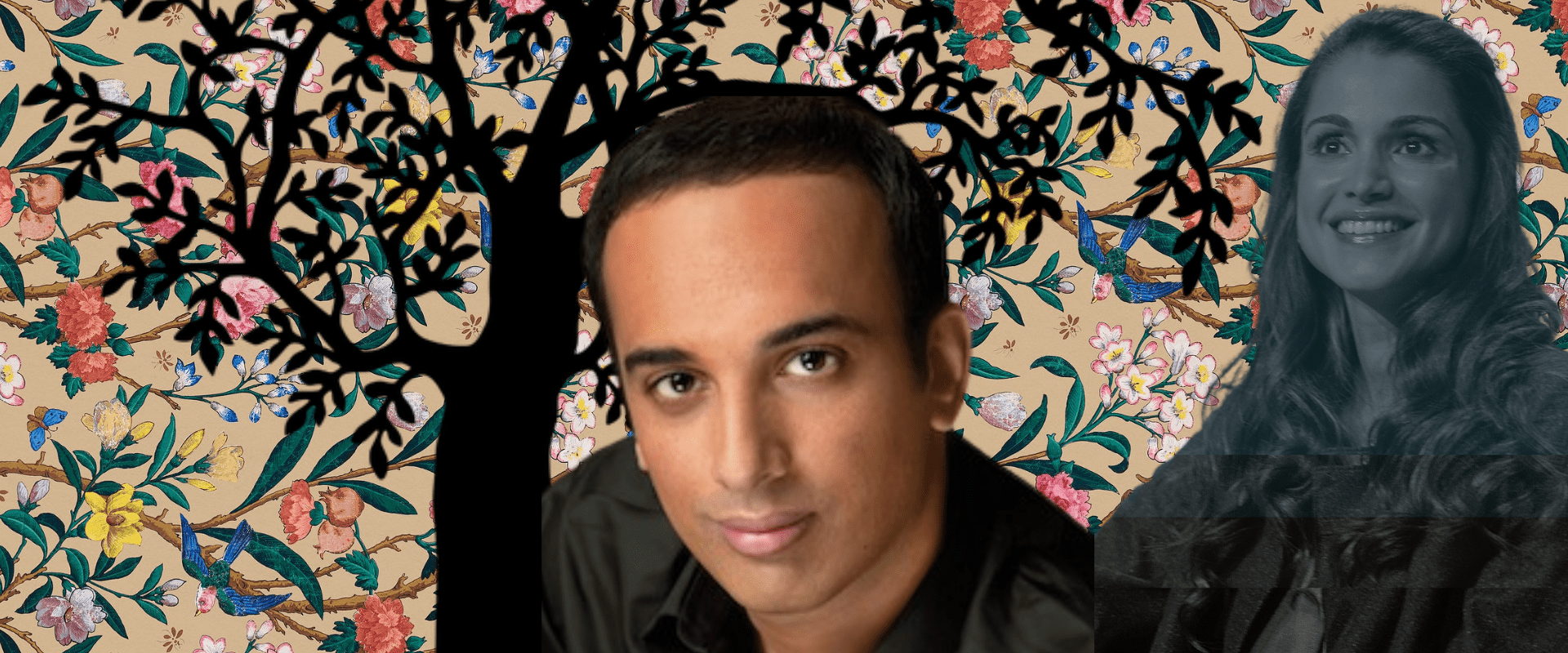

On March 29, 2020 – during the very early days of the pandemic – Israel Story fans from around the world tuned in for what was then still very much a novelty – a live online conversation. Mishy Harman “sat down” with Ghazi Albuliwi, the hilarious protagonist of one of our most outrageous early episodes, to hear what had transpired in the five years since his story aired. Has the fatwa caught up with him? And – most importantly – has he finally settled down?

Ghazi Albuliwi’s father was (supposedly…) dying of cancer when he begged his thirty-four-year-old son to find a nice Palestinian woman and get married. Guilt-ridden and dutiful, Ghazi traveled to Tulkarm, in the West Bank. There, he hoped to meet a mate as beautiful as the native Queen Rania. But – unsurprisingly perhaps – that’s where things started to turn south. And, today, well… let’s just say that Ghazi isn’t exactly a welcomed guest in the Palestinian city.

Act TranscriptGhazi Al-Buliwi: You can’t date without being married. That’s like the Islamic way, you can’t date someone without marrying to them. So it’s like the ultimate let’s-play-Russian-roulette-with-your-life way of marriage. Let’s get married and then let’s date.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Ghazi Al-Buliwi is a Palestinian-American writer and director. He was born in a refugee camp in Jordan and then, when he was two months old, the family moved to Brooklyn. That’s where he grew up and he is a Brooklynite, through and through. Ghazi’s family is Muslim, but he’s not religious. And that’s part of the reason why, at age thirty-four, much to his parents’ chagrin, he was still unmarried.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: In the Arab custom, the oldest son usually is the head of the family. That is the case here with me. Arabs will say ‘Abu,’ which is ‘father of’ and the name of the first son. And in my case, for my dad, it’s Abu Ghazi. He walks around with this title attached to me, whether he likes it or not.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): When you call someone Abu something, it’s a sign of both respect and familiarity. But it also creates this inextricable link between the father’s identity and the accomplishments and failings of his eldest son. Now, Ghazi’s single status is definitely seen as a failing. And in Arab culture it’s a failing for the same reasons as it is in Western culture. Basically, people wonder what’s wrong with you. And if you’ve ever been single in your thirties, you know what that’s like. For Ghazi, that pressure to get married? Is worse.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: It’s kind of like a scarlet letter. He’s walking around with this name attached to a son who is not married. Every time his relatives or those around him ask him anything, it’s like “so, oh… how’s your son, did your son get m—” “No.” Basically it depresses the guy.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): His parents offered to find him a nice Muslim girl, but Ghazi refused. The last thing he wanted was to get roped into an arranged marriage with someone too religious. So his parents nagged him. For years. And then Ghazi’s dad got sick.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: So, he had cancer of the kidneys, they removed one of his kidneys. The second operation when they removed another half, I’m walking home with him from the hospital and he just stopped me at a stoplight, and I remember exactly where it was, it was like Court and Warren in Brooklyn, and he turns to me as we’re waiting for this light to change, and he turns and he goes, you know, “I want to see your children before I die.” That statement right there propelled me to do things that I never thought I would do. So I did something very impulsive, I had a conversation with my mom, which I never thought I would have with her, but I was like, look, I wanna compromise with you guys. I want a woman who is more on the modern side of things. We’re Jordanian/Palestinian – I think Queen Rania of Jordan is amazingly beautiful. If I can find someone like Queen Rania of Jordan, I would be so happy. And so, my mom’s exact words, “Queen Rania? Yeah, her family’s from Tulkarm, where our relatives live. I’ll tell you what, in Tulkarm it’s like going to a lemon tree, you can pick all the Queen Ranias that you want. You can just pluck ‘em out.” And she did this thing with her hands where she mimed plucking a Queen Rania off a tree. And I’m like visualizing like beautiful women hanging like Queen Rania on a tree that I would just pluck out when I got there. So I book a ticket. I fly into Ben Gurion, where I was proceeded to be interrogated. And I had my American passport. An American passport has some cache to it. It’s not just any passport, it’s America’s passport. So I kind of walk up and there’s this girl direct people to either passport Israeli control or other international visitors passp— so I walk up to her. She looked at my thing, she looked at me. She… I now know she sees the Arab name, she goes, “what is your purpose to coming to Israel?” I said, “Umm, I’m gonna see my family in Tulkarm.” “Tulkarm?! Go over there, go to that…” And I turn around and I see this little room. It was like… It’s the equivalent of a smokers’ room, you know, they have these see-through windows, where people can just go in and smoke. It’s such a sad thing, you see people pacing around, smoking and just no one is smiling, no one is talking to each other. This was the same room but it was just full of Arabs waiting to be questioned by immigration. Israeli immigration. And then you’re in the little room, you’re kinda hanging out. And you’re wondering, well why are all these other people in the little room? I mean, I can understand the guy with the beard named Muhammad, who was there. I was like, ‘alright dude, you, I mean, come on, you know… what were you expecting? There’s no way they were gonna let you through.’ So you start judging other people in the little room. And then there was this one white European girl — Why are you here? And she was like, “Oh, I took Middle Eastern Studies back in Oxford.” I was like… ‘oh’… It’s like you just took the wrong class in college and she ended up in the little room. So I didn’t feel so bad after that.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Six hours later, Ghazi gets out of the airport and into a cab. The cab driver’s Israeli so he can’t go into certain areas of the West Bank. So he stops at the checkpoint near the entrance to Tulkarm.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: He lets me out, takes so much money, I grab my suitcase, I turn around and the guy’s… literally dirt is flying in the air, he’s already gone. And I’m like what the fuck is going on. And I’m walking towards the checkpoint. And now I’m walking towards soldiers, with a huge suitcase, who are literally looking at me with their guns up — not pointing at me — but they’re looking at me like, what is this fucking guy doing. And I’m like “Ohhhh shit.” This is when it dawns on me that you are… this might be a really big mistake, you should not have left Brooklyn. I get to the checkpoint thing, they look at me, they look at my passport. And… they let me in. So I go into Tulkarm and I grab a taxi there, go to what my father told me to go to, which is a section of the refugee camp that my family lives in – Harat El-Balawna, neighborhood of the Balawna. The Balawna is my family tribal name. And that is where I pull up. And… You know, meet my family. And then eventually they start taking me around to meet women. I think that first day we went to see two girls.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): So, in Western cultures, you have these dating rituals. The first date you go for coffee, or a drink — never dinner. You ask each other the same boring questions. And you basically know in twenty minutes whether or not you’re interested. In Arab culture, there’s also this matchmaking ritual. But it’s a little different. Here’s how it works:

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: You sit down, there’s the men of the girl’s family on one side of the living room, my family guys sit on one side. And then you’re just kinda waiting there, you’re kind of small talk, people are like chain-smoking in these rooms and like, I’m like from New York, I’m like dying here. And then eventually the girl, and it’s almost every time verbatim, the girl comes out with a tray of drinks. She serves all the men, the last drink is for you, she makes eye contact with you then sits with her relatives. And then you sit and you just stare at each other like something’s supposed to happen. It such a weird thing. But a lot of these girls would come out of these rooms and I’m thinking Queen Rania all the way. I’m thinking there’s gonna be a hot girl coming through this door.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): And the first woman he met was beautiful.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: Turned out to be my seventeen-year-old second cousin. She was actually kinda cute.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): But the cousin thing was a deal-breaker for Ghazi. And from there, things kinda go downhill.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: The whole time you’re there, you’re like, this is really not what I signed up for. I sat with one girl, Islamic girl who asked me, “Do you pray?” Because they made us sit — you’re allowed to like sit with the family and then you can sit privately but her brothers sit in a room like watching you. It’s like a double date with the brother who is like so like intensely Islamic, like staring you down, kinda. And so this girl — who’s a pharmacist, so you can go ‘oh, she’s like a scientist’ — she goes “oh, do you pray?” And I say “no, I’m gonna be very honest with you, I’m not gonna lie, I don’t pray.” She goes, “oh, you’re gonna go to hell.” I was like that just kinda just killed any kind of thought of this going anywhere, not that it was, but… I’ve been on many dates in New York where it’s not “you’re gonna go to hell,” it’s “can I have the check, please.” OK, I guess she’s not into me. This was like “you’re gonna go to hell.” I guess that was Tulkarm’s version of “can I please have the check.”

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): A week goes by. A week and a half. Ghazi’s going from house to house, drinking tea, meeting women — but his efforts are fruitless. On top of that, the conditions of the refugee camp are really starting to get to him.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: The refugee camp is just like such a depressing thing. Kids with no shoes on, people are poor, dirt everywhere, I would take three showers a day. Nice Jewish settlements with nice clean houses across the fence, which I watch every day. And I wish, why couldn’t my family have been Jewish settlers. Why? Why? So I had a nervous breakdown, nervous breakdown being you cry, scream, and then walk through a refugee camp just cursing yourself.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Eventually, Ghazi’s cousin finds him, wandering around the refugee camp, weeping, and he brings him back home.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: We come back and then like someone goes, “look, there’s this girl. Let’s just go see here, she’s at an amusement park with her mom, we know her, we already talked, they’re gonna meet us there.” So I go with my cousin and my niece, I’m not expecting anything, I’m already like checked out, I’m already going “I’m going back to New York, that’s it, I’m done, I kinda did what I had to do here for my father.” Get to the amusement park, meet the mom. She goes, “oh, she’s with her sister on the ferris wheel, why don’t you go see her, you know?” Alright, so I walk to the ferris wheel. And it’s a ferris wheel’s supposed to do a three-sixty, it’s supposed to do circles, but this is Tulkarm. The ferris wheel is not doing three-sixties, it is doing a one-eighty. So it would go up and then come down like a crescent moon. And so I’m thinking, alright, is this some kind of Islamic thing where it’s doing a crescent shape? No. And I talked to someone, it’s like no, man, man, everything is breaking down in here. The bumper cars are not bumping. They had like a zoo, the snake died, they told me. It’s like so sad, the conditions there. [laughter] I mean… Anyway, so I’m trying to figure out what this girl looks like because the ferris wheel is coming down, going up, coming down, going up. And now I’m fixated on a very overweight girl, I’m like ‘great, that’s her.’ So the ferris wheel thing stops and people start getting off — and as the overweight girl passes, doesn’t say an— I’m like, ‘okay, it’s not her.’ But this girl gets out, and I like focus on her, and the girl looked like Audrey Hepburn. She wasn’t wearing a hijab, very Western looking, had really cool looking jeans. I say hello to her, she was a little shy, we walk back to her mom, I sit with her mom, we’re talking. And she’s like completely shy. I’m like, it’s understandable this girl doesn’t want to say anything to me, right? The conversation turns to you know, whatever, ‘would you ever let your daughter go to live in America, you know I live in New York, it’s really nice there?’ Mom’s like, “yeah, totally.” And, you know, it was kind of a done deal there. I was like, ‘if the mom’s agreeing to this, it’s cool.’ I’m walking back with my cousin, I’m like “dude, done. Let’s just… I’m ready, let’s get the guys, let’s just do this.”

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: That next day, we go to the house, we do the sit-down with the men. We do this kind of ketuba. Ketuba in Arabic is kitab. Kind of haggling back and forth of how much money do we put for the muqaddam, which is what are you to put forward if she were to get divorce. It’s just to protect the woman in Islamic law. Ten thousand Dinars, which is about $15,000 back then, as I was told. Done deal. Let’s sign. Next morning. We go to the Islamic sharia court, and then I sign this wedding contract. And I sign it in front of the judge there, the Islamic judge.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): And now Ghazi and — let’s call her Farah — are legally married. They met the other day and now they’re married. So now they’re allowed to be alone in a room together.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: At that point, her family starts to allow me into their house, because I wasn’t allowed to, I was like a stranger, but now I’m like the son-in-law.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): So Ghazi’s staying with the family for a few days while they make arrangements for a big wedding party. And one night Farah walks into his room.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: She comes in and she goes, “oh, I wanna show you pictures of my brother.” Who… Her brother’s a police officer in training. She comes from a cop family. And she opens up this folder and there’s a bunch of photos in there. It’s just photos of her brother doing kind of like an obstacle course, he’s climbing the rope. He’s like running, it’s hot out, you can see guys with their shirts off. And then at a certain point it’s him posing with his shirt off. [pause for a beat] And then him posing with a shirt off with a gun, like a machine gun, cigarette in his mouth, like seductive pose. And then she turns to me, she goes, “isn’t he tasty?” “huh? isn’t he tasty?!” And she goes, “can’t you see why all the girls want him?” I’m like, “huh?!” But the way she said it, I’m like, “what the hell just…” It’s like the fourth day and I’m like, “this family’s nuts!”

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): And at this point Ghazi’s also beginning to realize that the family is using him for his money.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: I’m buying them stuff, buying them groceries. There asking me… I’m like, ‘this is weird. This is not…’ As an Arab guest, usually Arabs are supposed to be… You’re the guest you’re not supposed to buy anything. This is the opposite.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): So Ghazi makes a decision.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: We’re gonna go buy a wedding dress the next day. If she asks for an expensive wedding dress, I’m done with her, I’m gonna tell her I can’t marry you.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): And sure enough, the dress that Farah and her mother pick out is really expensive.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: I kind of was like, “tell her we’re going to another wedding gown store, I think that’s a little high.” Mother comes out – doesn’t look happy. My wife comes out – doesn’t look happy. We start walking — silence. And I turn to my wife. I’m like, “Uhh…what’s wrong?” “Oh, you know what’s wrong. You shouldn’t have upset my mother.” She said it in such a way that I just stopped. It’s been building up. I was like, “you know what, I can’t do this. I divorce you, I’ve had enough of you.” Turned around, I left her in that sh- that was the last time in my life I ever saw this girl. I walked to the refugee camp, right, from the town center. Tell my uncle, I gotta get out of this. He says don’t worry, don’t worry, stop, stop, don’t cry. I’m like crying, I’m a 34-year-old guy crying. I’ve been like robbed at gunpoint in Brooklyn and I never cried then. I peed on myself, but I didn’t cry. And here I am, walking through this refugee camp, just crying, just like… a grown man crying. He’s like stop, don’t cry, I know this great lawyer. I’m like who’s this lawyer? He goes, don’t worry, he’s the best in Tulkarm, his name is Arafat Arafat. It was enough to make me stop crying and go ‘Arafat Arafat?’ He’s like Yes, Arafat Arafat, he’s the best lawyer in all of Tulkarm.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): So Ghazi walks back into town to meet the lawyer.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: The guy’s wearing like shorts, like a mickey mouse t-shirt or something. He’s like “tell me, what happened?” I was like “Arafat Arafat, this is what happened.” He goes, “did you enter her?” And then he made a hole with his finger and he put the — I said “no, I tried to, I wish I had entered her.” He goes “ok, that’s good, that’s good, and he sits back in his chair and he thinks, ‘that’s good.’ I said, “listen, I gotta get out of here, I’ve had it, I’m… nervous breakdown, I’ve been crying, look at my eyes.” He goes, “why were you crying? Cuz’ men don’t cry!” I’m like, “this is too much for me.” He goes “don’t worry, I’m gonna make it all better.” He goes “sign this, it’s a power of attorney, I will be you here in Tulkarm. Go back to America, I will take care of this for you!” And then I go home and I get a call from her uncle, the chief of police, who as I know now is a nut job. He has had people’s legs broken for my wife, just whistling or like saying something to her in a like a come-on way. And sending people to like break their legs. Two guys ended up in wheelchairs for like two months — something like that, some weird beat-down. Now this is the guy that’s calling me that’s saying “I’m gonna send a police car to come get you. And we should really talk about this because you’re not just gonna leave her here like this.” I’m like, I started freaking out, this guy’s gonna kill me. I said “listen, I’m really emotional, I can’t talk right now, I need to drink some tea, relax. I’ll come see you in the morning.” He goes, “you’re gonna come in the morning?” I was like, “yeah, where am I gonna go? I’m in Tulkarm!” He goes, “alright, I’ll send a car for you in the morning.” Hung up the phone. Ran into my room in that refugee camp house of my uncle’s. Packed that suitcase up, everyone had gone to sleep. And I just lay there with the suitcase, holding the suitcase like it was my mother. And every time a light would come under the door, I’d think, ‘they’re coming for me, they’re coming… they’re gonna come get me.’ And I wait, I know the busses start running at like five. I pick up that suitcase, I don’t even say anything to the relatives, I run through that door. And now I’m running through the refugee camp. It’s like semi-dark, the sun is coming out. Chickens are like cackling [imitates chickens]. And I’m running with this suitcase on my head and I’m like running through alleyways. People are in their underwear. I see people through windows. I see people having breakfast. I see the news. I’m like running through dark alleys, and I get to the bus, get on that bus, that yellow bus, I remember getting on that bus and I’m like ‘oh, please don’t let them stop this bus at the checkpoint.’ Got past the Palestinian checkpoint, get to the Israeli checkpoint. Now we’re on our road. End up in Ramallah.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): And then he makes it to Jerusalem, where he gets a hotel room and hides out until his flight back to New York. Meanwhile, the men from Ghazi’s family and Farah’s family hold a meeting to discuss the divorce. Because this is not just an issue between two people. When Ghazi abandoned Farah, he didn’t just mistreat her — this was an affront to her family.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: And then it came out that I had, in my hysteria, told someone in town that she’s having sex with her brother. I said, “she’s not gonna have sex with me, she’s having sex with her brother.” Because of course I’m having a nervous breakdown. And this, coupled with the fact that I just divorced her, got back to the brother. So the brother, said “he had dishonored my family by saying I had sex with my sister. I issue a fatwa against this guy. If he is to show his face in Tulkarm at any point, I will kill him dead in the street.” The men in my family didn’t really put up a fight. They said, “this is our son, we really would hope you’d reconsider.”

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): About a week later, Ghazi makes it back to Brooklyn, fully intact, and he talks to his dad about what happened.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: Oh, it was like nothing. It was like, “oh, you’ll get better. It’s OK.” It was like such a nonchalant — Oh, here’s the punch line: Was not dying.

Shoshi Shmuluvitz (narration): Yeah, it’s now four years later, and Ghazi’s dad is still alive. Ghazi is thirty-eight, still single. And his parents are still trying to get him married. Not only that, they still want him to marry in the traditional way, the way he did with Farah.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: He just Jewish guilted me in his own Arab way to get married for him. And you know, I kinda feel it still. You love your parents so much that you end up hating yourself. And that’s where I am today: I love ‘em so much that I hate myself. Look at what I did! I got married and I had nervous breakdowns and I hate myself for doing it. I should not have done that. But I did it because I love ‘em.

Mishy Harman: Welcome to everyone. As you will recall, this whole adventure in Tulkarm went horribly wrong, and Ghazi fled in the middle of the night. And there is a fatwa issued against Ghazi in Tulkarm. So I guess Ghazi, the first question on everyone’s mind and definitely on my mind is, have you been back?

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: No, no, no, no. I mean, I really take those things seriously. There’s a whole story behind what happened after the fatwa and after I left and I went back to New York. Because if you remember the story, I hired a lawyer, the best divorce lawyer in Tulkarm was named Arafat Arafat. His office was above the fruit and vegetable stand in the produce market area of Tulkarm. And I am not making this up. It was a hole in a cave. When I went in with my cousin to see Arafat Arafat, we ducked down. We were walking in this cave and I can hear an echo as I was talking to my cousin who’s in front of me. So what happened was I left Tulkarm in a hurry, as you know. But I had not divorced her legally. And Arafat called me up one day and said, “look, you owe her fifteen thousand JDs.” Because in the ketuba or the kitab, both are the same, you write a dowry. If you divorce her, you give her this much money so she can move on with her life. Mine was about fifteen thousand dollars. He said, “you’re not going to pay that. We will let her wait it out.” It went on for two years and then one day he called me up. He said, “look, five thousand dollars, send it to me, I’ll get you divorced.” I was so happy after two years of this. Called him in a week. His phone was disconnected and no one in Tulkarm knew where Arafat Arafat was. And my five thousand was gone. My parents eventually got frustrated where they felt the only way they can get me married really again is to go there, search for him, get me divorced. So that’s that whole other part two to this story.

Mishy Harman: So your parents returned to Tulkarm and managed to actually…

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: They went back there, yeah. Eventually he got me divorced. And here’s the hilarious thing, this is what Arafat Arafat said, after all of these two years thing where I sent him five thousand dollars. The reason he didn’t get me divorced in two years is I didn’t pay the twelve dollar application fee on top of the five thousand dollars.

Mishy Harman: So once your mom secured your divorce, did you all go out and celebrate and then she could once again be on your case to get married?

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: They were ready trying to get me married when I got home after Tulkarm. They were like, “oh well.” What did they say in Arabic? Mafi nasib. There’s no luck on this one. Next one, you’ll get it, you know? It was really that blasé.

Mishy Harman: How old are you now?

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: Forty-three.

Mishy Harman: And are you married?

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: I am not married.

Mishy Harman: Oh, man.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: I will soon be married, I think.

Mishy Harman: Really?

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: Yes. Her name is Raquel. Very lucky.

Mishy Harman: Is she Palestinian, Raquel?

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: No, no, no. Raquel is Mexican. Mexican-American.

Mishy Harman: How did that go over?

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: You know what? My mom saw a photo of her. She hasn’t met her yet, because she lives down in Louisville. You know, I have been, you know, trying to set her up, just mentally, getting her ready, that she is about to experience something she has probably has never experienced in her life, with my parents, especially with my mom, you kno

o you think that the requirements, once you pass forty, are somewhat lessened? That, you know, your mom just really wants you to get married, so it doesn’t really matter who?

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: Oh man, let me tell you. Mid-twenties – Let her be Muslim, let her be Arab, let her be from Jordan, from Amman, right? Years go by, let her be Muslim, that goes out till just let her be Arab, then further down, let her be a woman. Let her be a woman that has all her teeth.

Mishy Harman: And last question comes from Zev in Jerusalem. And he says that your parents were clearly so involved in your love life and who you marry, your future family and what what expectations or hopes do you have now that you’re going to get married for your future family?

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: My expectations for my kids? Don’t fuck them up the way my parents fucked me up, you know? Just basically… Just let your kids be. You know, I mean, I don’t know what else to say because, you know, to control your children is, I mean, you end up getting married in Tulkarm. I mean, that’s what can happen, basically. So that’s a warning, really.

Mishy Harman: Well, Ghazi, Mazal tov on your upcoming wedding. I hope, I hope, that there is a great Mexican-Palestinian party in the works for after COVID-19 days. And thank you, my friend. Always good always good talking to you.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: Yeah, yeah.

Mishy Harman: Thanks so much, bye guys! Lehitraot.

Ghazi Al-Buliwi: Bye!

The original story was reported, produced and scored by Shoshi Shmuluvitz, with music from Podington Bear. The update was produced by Skyler Inman, Yoshi Fields and Marie Röder. The end song, “Seen,” is by Tzachi Halevi and Lucy Aharish. It was written and composed by Diane Warren and produced by Tal Forer.