It’s springtime in Israel and renewal is in the air: Wildflowers are blooming, short pants make their first appearances of the year, and – most importantly – we are back with the start of our third season. But of course, it wouldn’t be Israel Story if there wasn’t a twist, and indeed our season opener takes us… right to the end. So tune in for an episode full of surprising stories that explore how we die, and what comes next.

Prologue: A Gift from Savta

When host Mishy Harman’s grandmother Zena passed away in January 2013, three months shy of her 99th birthday, the entire family spent the night huddled around her body, keeping it company. Not only did this somewhat macabre pajama party soon turn into a sweet memory, but it also produced a wedding and an adorable toddler, Shai Zena, who has exactly three things on her mind: Vanilla cake, yellow and purple cars, and… you guessed it – chocolate cake.

Mishy Harman (narration): In the winter of 2012, my older brother, Oren, got a phone call from a close friend of his.

Oren Harman: He said, “listen, I swim with this girl. I don’t know her too well, but she’s a really beautiful swimmer. [Yael laughs]. And you can know, you can know… [Oren laughs], you can know eighty percent of a person’s character from the way they swim. [Yael laughs]. So I… I suggest that you meet her.

Mishy Harman (narration): Later that day, Yael, the swimmer, also received a call.

Yael Barash: Yes, so my coach called me and he asked me, “can I introduce you to some guy?” And I said, “sure, I would love to!”

Mishy Harman (narration): The swimming coach gave Yael my brother’s name, and she – of course – began googling. At some point she came across an old TEDx talk he had given. Her initial reaction?

Yael Barash: Well… First I thought he’s a bit chubby [Oren laughs], cute. Definitely cute, but eh… just a little bit chubby. [Oren laughs]. But I thought I will give it a chance. [Yael laughs].

Mishy Harman (narration): They spoke on the phone, and set up a date, in Tel Aviv.

Yael Barash: OK, so Yekkes typically come on time, but Iraqi are… (and I’m Iraqi) come ahead of time. And I tried really hard not to come early. I thought a man should wait for a woman, and, you know, strategically I thought it was wrong [Oren laughs] to come ahead of time, or early. So I tried to keep busy and not to be early but eventually I arrived and Oren wasn’t there. I was, again, too early. I thought he should wait for me, but…

Oren Harman: Aha-ha.

Yael Barash: I waited for him. Then I saw him from far away arriving. And he had like a light blue shirt, and a short pants. And you looked very… You were very good looking man. Though the cutest part of your dressing was that you missed a button [Oren laughs]. You know it was so cute to see you with this open shirt, and missed a button and shorts, and I thought, ‘wow, what a man!’ [Yael laughs].

Oren Harman: [Oren laughs] Thank you! Let’s just say it was pretty unusual date for me too. Cuz’ when it ended we walked towards the boulevard, remember? And ahhh… you know we were about to say goodbye and suddenly you… you pounced on me and gave me a kiss. Remember?

Yael Barash: Yeah, I… It wasn’t exactly like that…

Oren Harman: It was… [Oren laughs] It was exactly like that! It was, it was quite a kiss.

Yael Barash: Thank you.

Mishy Harman (narration): My brother was super enthusiastic, and they began going out. Everything, at least outwardly, seemed to be promising. But…

Oren Harman: Then after about three weeks, I said to Yael, ”look, I really like you, ummm… But I… I’m sorry I really have to think about it a little bit more.”

Yael Barash: Yes, you said that you needed a break. But breaks are the most annoying things in relationship. Like, what’s a break? What do you need? Half-an-hour break? Day? Two days? How long of a break do you need?

Mishy Harman (narration): Oren didn’t really know what to say. So Yael? She decided for him.

Oren Harman: She said, “don’t call me for a month.”

Yael Barash: Yes. [Yael laughs].

Mishy Harman (narration): So Oren and Yael were on some sort of undefined hiatus. He constantly told us, (and this was nothing new), that he wasn’t sure, and didn’t know. Anyway, the month-long-break was supposed to end, or be reevaluated, on his fortieth birthday, January twenty-fifth.

Oren Harman: And then on the twentieth of January, I met up with my best friend on the boulevard, and he said, “Oren, your choice has nothing to do with Yael. You have to choose whether you want to continue to be a single guy, living in Tel Aviv, having fun, or to become a family man. And in both routes you’ll have great highs and happinesses and really frustrating lows, but that’s the choice you need to make.”

Mishy Harman (narration): Oren thought about his friend’s advice, and then said to himself, “yalla, al ha’chaim ve’al ha’mavet,” sort of the Hebrew equivalent of ‘here goes nothing,’ or ‘it’s now or never.’

Oren Harman: The very evening, I ran to your house, on Sokolov Street number 8, I remember it: I ran and I ran and I ran and ran until I got to your door, I knock on your door with the thought of saying – “come on, let’s go for it!’

Mishy Harman (narration): But Yael… wasn’t home. Oren called her cell, and when she picked up, she said that she was visiting a friend in the Golan, that there was almost no reception and that she could barely hear him, so they better just talk properly when she returned, as planned, a few days later on his birthday. The next day, Oren and I went to have dinner with our parents, in Kiryat Yovel, in Jerusalem. Now, we all grew up at 53 Shmaryahu Levin Street, right across the street from number 50, where my dad’s parents lived. My grandfather Abe had died many years earlier, when I was in third grade, but my grandmother, Zena… she was still alive and kicking, and almost ninety-nine. In any event, we all sat down to eat.

Oren Harman: And suddenly there was a phone call from the other side of the road, from Savta’s house. It was Melnie, her caretaker, she was hysterical and she said, “come, come, come over. Mrs. Harman not feeling well.”

Mishy Harman (narration): Oren, my father and I quickly ran over. We went straight into the den, where Savta was sitting in her favorite purple armchair.

David Harman: She was just breathing heavily.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s my dad, David.

David Harman: She had a small smile on her face. And she gradually breathed less and less heavily, as we were standing by her side.

Oren Harman: We held her hand.

Mishy Harman: And we actually, didn’t really say anything to each other.

David Harman: No. No. We didn’t.

Oren Harman: I think we all just realized what was happening.

David Harman: At a certain point she just stopped breathing. Very simply. She just stopped breathing.

Oren Harman: And with her last breath, a small tear fell down Savta’s cheek.

David Harman: What is called in Hebrew a “mot neshika” – a kiss of death. And it was over.

Oren Harman: That’s it, Savta was gone.

Mishy Harman (narration): Now, even though my Savta was so old, we were all pretty stunned by her death, because there was no preparation, or illness, or hospitalization. I guess we all just figured she’d go on living forever. Within a few minutes, the Magen David Adom paramedics arrived, and we had to convince them that there was no need to try and resuscitate my Savta. Then the police showed up, because that’s what happens when someone dies at home. And once they left, we were alone, just the family, with Savta. We tried reaching the Hevre Kadisha (the Jewish burial company), so that they could come collect her body. But no one answered the phone, because it was after 11pm, and the very next day there were elections to the Knesset. (Clearly they just assumed that people would be so eager to vote, that no one would even think of dying the night before the elections). Finally, around two in the morning, we managed to get ahold of some sleepy officer on duty.

Oren Harman: He said that they couldn’t make it that night, and we should sleep with Savta’s corpse and keep her company. Ummm, and so we covered her body with a sheet, and that’s it, we just stayed with her, it was a quiet night.

David Harman: We all sat there with her, ummm… and thought about Savta, each one his own thoughts, his own memories, and we felt that we were there in her last evening. We were all there together.

Oren Harman: We all really felt that we were with her, accompanying her on her last night in her house.

Mishy Harman (narration): Gradually, all the grandchildren brought sleeping bags and blankets and spread them around Savta. It was sort of like the pajama parties we used to have there when we were kids.

Oren Harman: We all just slept next to Savta on the floor.

Mishy Harman (narration): Throughout the night we talked, laughed, reminisced.

Oren Harman: It was all really sad. She was our mother, she was everyone’s mother. She was the mother of our family.

Mishy Harman (narration): Now, that very night, you might recall, Oren was still in the middle of his ongoing saga with Yael. Sure, there were four more days till his birthday, the scheduled deadline, when they had agreed to talk. But Oren? He couldn’t wait.

Yael Barash: Then Oren called me, and he sounded really sad and miserable, and he told me that his grandma just… his Savta, just died. And that you were all with her through the night. And I knew Savta. I’ve been to one of the Friday night dinners, and I saw how all the family comes and sit around the table with her. And although she didn’t talk, she was the center of the evening. And I knew that it’s something really dramatic happened, and I really wanted to be with him.

Oren Harman: The next day, Yael showed up and pretty much stayed for the whole Shiva.

Mishy Harman (narration): And, before any of us really understood what was going on, Yael had transitioned from being this girl Oren had briefly dated, to sort of being a family member.

Oren Harman: Yael really was with us, almost like a part of the family. And I… I didn’t realize it at the time, I don’t think, but I guess my heart already knew. And five weeks later we were engaged.

Yael Barash: Yes! We were on a trip in Amuka and suddenly he went down on his knee and he gave me a blade of grass made into a ring, and ask me to marry him.

Mishy Harman (narration): Oren had waited for forty years to find a bride, but all at once his patience was up. And everything happened very quickly.

Yael Barash: We got married in June 2013, and a year later, in June 2014, our daughter was born.

Mishy Harman: Chuchi, what’s your name?

Shai Zena Harman: Shai Zena!

Mishy Harman: Shai Zena?

Shai Zena Harman: Yeah!

Mishy Harman: Shai Zena Harman?

Shai Zena Harman: Yeah!

Mishy Harman: And who are you named for?

Shai Zena Harman: For Savta Zena.

Mishy Harman (narration): Shai, in Hebrew, means gift. So little Shaizee was really…

Yael Barash: A gift from Zena. From Savta Zena. Because we felt that thanks to… in a way, thanks to her death, we got back together and Shaizee was born.

Oren Harman: And I guess Savta leaving us was sort of our family’s beginnings, and it was very joyous.

[Shai Zena singing]

Mishy Harman: Shai Zena?

Shai Zena Harman: Yeah!

Mishy Harman: Was Savta Zena old?

Shai Zena Harman: Yeah!

Mishy Harman: How old?

Shai Zena Harman: Ummm… This old.

Mishy Harman: Are you showing me with your hands?

Shai Zena Harman: This old. [Yael laughs].

[Music comes up]

Act I: Over My Dead Body!

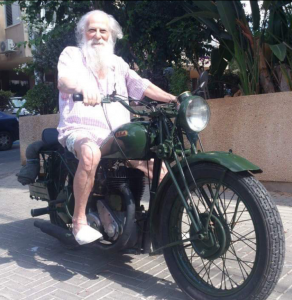

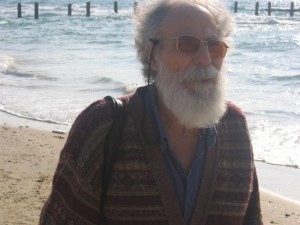

Meet Shlomo Avni, a prophet-like, quixotic octogenarian from Givatayim, who devoted the last few years of his life to an uphill battle. Forgoing precious time with his children and grandchildren, he decided to take on the State of Israel and what he saw as its absurd burial regulations. Shlomo’s request was seemingly simple: to allow his son to place his corpse in nature, where it would become an (unusual) meal for wild animals. Yochai Maital brings us the story of an epic crusade that involved irate orthodox members of Knesset, Supreme Court rulings, Kafkaesque committee meetings, custom-made iron cages and, ultimately, an unexpected aquatic resolution.

Shlomo Avni: You see, death… Well, it’s just a part of life. We were all born to live, to grow old, to die, and then to nourish the creatures that nourished us our whole lives. In the end, we all have the same simple mission: To die and become nourishment for others. But for some reason, we’ve decided to disrupt nature.

Yochai Maital (narration): Meet Shlomo.

Shlomo Avni: My name is Shlomo Avni, I’m eighty-three years old, and all I can say is that I’m waiting around to die. To be buried at sea.

Yochai Maital (narration): And with that, let me introduce Shlomo’s two children – Noga and Eyal.

Noga Avni: It all started as a running joke my dad used to tell us. See, my brother Eyal and I, we both had dogs.

Eyal Avni: I raised two wolf-dogs. And my dad told me that after he will die, he want me to cut his body to pieces, put them in the fridge, and give the dogs to eat his body. My dad had a strange sense of humor, so it was for me another joke. It wasn’t a funny joke for me, but it was a joke, a very bad joke…

Yochai Maital (narration): But the thing is, Shlomo wasn’t kidding. He was – please excuse the pun – dead serious.

Shlomo Avni: Let the dogs benefit from my death. I mean, they love meat, and I am meat, so why should they not eat me? They deserve to. Look, I feel uncomfortable among humans. I’m a troublemaker. I mean, I guess you could say that I’m the bad boy on the block.

Yochai Maital (narration): This is a story about one man who dreamt of returning his body to nature. But that dream came up against a huge wall. A wall called… the State of Israel. Shlomo dedicated the last years of his life to climbing over that wall. It began with that running joke of being fed to the dogs. For a long time, nobody in the family took him seriously. Till one day, in the middle of a casual Friday night meal, Shlomo put it in very clear terms:

Shlomo Avni: I said, “I don’t want to end up in a cemetery. I don’t want to be buried in the ground.” Why? Because burying people in the ground and then covering them up with concrete and cement is like turning the earth into a can of sardines for human bodies. This is blasphemous. It’s basically a desecration of the dead. A desecration of life.

Yochai Maital (narration): Shlomo imagined a different ending for himself. He wanted, very simply, to be laid out in nature, where he’d become food for wild animals.

Eyal Avni: I told him, “OK, you want to bury like that? I’m not going to do all the bureaucracy at the day that you’re going to die. I don’t want to take care of anything. You’ll get the permissions, and if you get them, I will do that.

Yochai Maital (narration): Without missing a beat, Shlomo said:

Eyal Avni: “No problem, I’ll do that.” At the same moment he went to the computer and started to write the letters.

Shlomo Avni: I didn’t think there would be any problem. I wrote down a will and requested that when I die, my son be allowed to take my body and throw it in the wild.

Yochai Maital (narration): A few days later, Shlomo stood on line at his local Givatayim post office branch. He licked a couple of stamps and put them on a large manila envelope containing his will. It was addressed to the Aputrupus Ha’Klali, the governmental agency that deals with anything related to inheritance and estates. But when they received the unusual request, they quickly returned it to the sender, together with a short explanation saying that they could not, unfortunately, authorize the will. The reason they gave was simple – it just wasn’t legal.

Shlomo Avni: So I had no choice: I turned to the courts.

Yochai Maital (narration): Shlomo’s petition?

Shlomo Avni: To be allowed to carry out my desire to be buried in nature. For the simple reason that I’m the master of my body. Society doesn’t have any rights to it. My body is mine. It doesn’t belong to the community.

Yochai Maital (narration): So who does one’s corpse really belong to? Thanks to Shlomo, this seemingly absurd question got a lot of attention in Israel. It was debated back and forth between different courts, till it ended up, in November of 2009, at the doorstep of Baga”tz, Israel’s Supreme Court. The verdict, at least from Shlomo’s perspective, was very disappointing.

Eyal Avni: The Supreme Court told him that he won’t be able to be thrown in the nature, in the desert. It’s not suitable that someone will walk in the desert and will find his body. The common good is more important than the individual good.

Yochai Maital (narration): In addition to the issue of making sure that random weekend hikers don’t stumble upon a rotting corpse, the justices also cited the Prophet Jeremiah and Maïmonides, stating that – and I quote – “Jewish law requires burial, and any other alternative is considered a degradation of human dignity.”

Shlomo Avni: They claimed that my wish offends human dignity. But I said, “I am the human! It’s my dignity we’re talking about here! Let me define what offends my own dignity!” But it was too late, they had already decided.

Yochai Maital (narration): So you might think the story would end here. I mean, the highest court in the land had ruled on the issue. But if there’s one thing you can say about Shlomo, it’s that he just doesn’t give up.

Eyal Avni: He went back home to sit on his drawing table, and he had a new idea.

Shlomo Avni: I suggested an alternative: That my son throw my body into the sea. I mean why not? The sea is deep enough and wide enough to accommodate all the cemeteries in the world.

Yochai Maital (narration): This new petition bounced around the courts for years. The State attorney basically argued that Shlomo’s aquatic solution was nothing more than him being a wiseass; that it wasn’t substantially different from the idea that had been thrown out by the Supreme Court. They demanded that it be rejected outright. But Shlomo, who insisted on representing himself, fought on. Each time he’d lose a hearing, he’d just appeal to another jurisdiction. Over and over again. And as this protracted legal battle went on, it took over Shlomo’s life. That, you might imagine, wasn’t so simple for his family. When I asked him about it, his gaze turned serious, as if I had touched on a particularly raw nerve. He went all quiet, and then… blurted out a single word. An acronym, actually.

Shlomo Avni: Zabasham.

Yochai Maital (narration): Loosely translated: “That’s their fucking problem.” When I pushed Shlomo on this point, he said that his wife was at peace with his macabre crusade.

Shlomo Avni: She understood my point of view. She even accepted it. And so did my children and grandchildren. They all justified me.

Yochai Maital (narration): But Noga, Shlomo’s daughter, tells a slightly different tale.

Noga Avni: When a person fights for a cause, he makes many sacrifices along the way. In my dad’s case it is my mom, and us, his kids. All of his spare time is dedicated to this battle. A battle about his death. And it’s hard, because it confronts us with the idea of him dying long before we need to. I mean we always have this thought, in the back of our minds, of what will happen when our parents will pass away. But in our case, it’s a daily reality. It’s so present.

Eyal Avni: The price that we as a family paid was a very high price, very heavy one. I won’t exaggerate if I said that the family was in the second priority for him.

Noga Avni: Look, I think that all the rituals surrounding death are completely unnecessary. I kind of despise them, to be honest. And what my dad is doing is essentially forcing us to think about them, all the time. I mean, I think we should celebrate life. In a big way. But when it comes to death, I’m all for getting it done as quickly and practically as possible. I don’t like to think about death. But apparently my dad does. He likes it very much. See, I don’t appreciate Don Quixotes that much. I even feel some sort of contempt for them.

[Musical beat]

Noga Avni: The person who took it the hardest was my mother. She’d suffer episodes of severe anxiety and depression.

Yochai Maital (narration): In the middle of it all, Shlomo’s wife was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and her memory quickly began to fade.

Noga Avni: It’s possible that, in a way, Alzheimer’s sheltered her from this frightening subject. In that sense, at least, she was spared some of the pain.

Yochai Maital (narration): Ultimately, Shlomo’s final appeal brought him back to the Supreme Court. And this is when things began to change. In what was somewhat of a surprising reversal, the Court acknowledged that there was, in fact, no law that allowed the State to force a person to be buried against his or her will. They knocked the case back down to the District Court for further consideration. It wasn’t a slam dunk for Shlomo, at least not yet. But it did give him some hope. Yet another set of hearings soon began, and the State, well, they tried out a new line of reasoning.

Shlomo Avni: They said that I am waste, garbage, and that throwing my body into the sea would be tantamount to polluting it. I said, “I’m very sorry, I am not waste and I’m not filth!”

Yochai Maital (narration): The only way you’re allowed to throw garbage into the ocean, is by obtaining a special permit from the Committee for Discharging Materials to the Sea.

Shlomo Avni: So I had no choice. I went to talk to the committee.

Yochai Maital (narration): The committee is made up of ecologists, marine biologists and experts on industrial waste. Usually they get together to discuss chemical spills, and large scale pollution caused by factories or oil tankers. But now, by court order, they convened to debate one single matter – whether Mister Shlomo Avni from Givatayim was, indeed, trash. At the end of a very, very long meeting on this weighty matter, they made up their minds. The next day, Shlomo was notified, much to his delight, that he was not garbage. It was a cathartic moment for him. After years and years of fighting what he saw as Israel’s absurd burial regulations, he had prevailed. Shlomo had single handedly created a legal precedent. It now seemed as if the Mediterranean tunas could start drooling, in anticipation of the delicious meal that was headed their way. But the main course himself was still worried. And for good reason.

Shlomo Avni: Even though I won, and the Court said that my son can fulfill my wish, I’m afraid that it’s still gonna be an uphill logistic battle for him when I actually die.

Yochai Maital (narration): Shlomo was right. Shortly after the verdict was handed down, three ultra orthodox Members of Knesset – horrified by the potential ramifications – introduced a bill that would require the State to bury every Jewish citizen, including… Mister Shlomo Avni. The bill never passed, which – of course – made Shlomo happy. But his kids knew that this meant that when the day comes, they’d be the ones who would have to deal with the morbid task.

Eyal Avni: I don’t know how am I going to be in the money time, in the real time. Am I going to fell apart? Am I going to be emotional to break because my father just died? Maybe I want to break, I want to be his son not the producer of the funeral.

Yochai Maital (narration): Shlomo wasn’t too worried about all this. As far as he was concerned, he was ready to go.

Shlomo Avni: For the last thirty or forty years, I’ve lived against my will. I don’t bless this life. I curse this life.

Yochai Maital (narration): Those were Shlomo’s parting words to us, when we first met him, nearly three years ago. From time to time we’d check in with him, to see how he was doing. And each time he’d confirm that he was still very much alive, and very much unhappy about it. And then, on the first of March, 2016, while taking a nap in front of the TV on his favourite armchair, Shlomo Avni died. He was eighty-six years old. Eyal, his son, was the one who found him. He was sad, of course, as anyone would be. But at least one thought gave him some peace of mind.

Eyal Avni: In terms of the funeral, everything is organized. We had plates with vegetables, tray of fruits, exotic fruits, pastels.

Yochai Maital (narration): You see, anticipating his children’s emotional state, Shlomo didn’t breathe his last before finalizing all the logistics of his burial at sea.

Eyal Avni: We had filled grape leaves, filled cabbage leaves.

Yochai Maital (narration): A pre-signed contract with a boat owner, a detailed guest list….

Eyal Avni: Sandwiches with salmon, cakes, burekas.

Yochai Maital (narration): And, of course, also…

Eyal Avni: A lot of alcohol, a lot of beer. My father wanted it to be a celebration.

Yochai Maital (narration): Everything seemed to be in place for Shlomo’s much awaited send-off. But you know how life is sometimes: You make plans and then some shady boat owner screws you over.

Eyal Avni: The second or the third phone that I’ve done after my father died was to the owner of the ship.

Yochai Maital (narration): The guy told Eyal that he was very sorry, but he couldn’t take them out to sea, since his boat, it didn’t have the right kind of license. It had taken Shlomo a long time to find this boat, and Eyal was afraid that now – with his dad’s body waiting at the morgue – some silly licensing issue would stop him from fulfilling his final will. So, in a frenzy, he began making phone calls. Hundreds of them. He talked to yacht owners, skippers, fishermen. When that didn’t work, he moved on to…

Eyal Avni: Very big ships.

Yochai Maital (narration): Shipping companies. He even contacted a helicopter operator who could maybe drop Shlomo’s body into the sea from mid-air. Nothing panned out. But just like his father, Eyal wasn’t about to back down.

Eyal Avni: I’m going to fulfill my father last wish. I’m not going to give up. And if I will have to, I will take a hasake…

Yochai Maital (narration): (Hasakes are those giant surfboards that Israeli lifeguards have).

Eyal Avni: And I will paddle to the middle of the sea, I will throw his body. But I’ll know that I done that thing that was so important for him. I’m not going to give up.

Yochai Maital (narration): Almost out of options, Eyal reached out to Shmulik and Vered, a couple who live on a yacht parked in the Tel Aviv marina. They were game. But there was one pressing matter:

Eyal Avni: Shmulik told me that we 0nly have three hours to leave shore. I asked him why. And he said, “we have a window of opportunity before the storm is going to come.” I said to him, “Shmulik, it can’t be, I can’t arrange all the arrangement in three hours there are so many things to do. It’s impossible.”

Yochai Maital (narration): But on second thought, Eyal knew that for an Avni, nothing is really ever impossible. That the longer he waited, the more likely it was that some orthodox politician would try to find some loophole or pull some strings that would bring the whole project to a halt. He knew it was now or never.

Eyal Avni: So I said OK, we have to open a war room.

Yochai Maital (narration): Like a skilled commander, Eyal quickly assigned assigned tasks: His sister Noga dealt with…

Eyal Avni: All the issues of the permits and licenses.

Yochai Maital (narration): Two other friends were responsible for getting…

Eyal Avni: All the food, drinks, alcohol, etc.

Yochai Maital (narration): A third friend showed up with a big pickup truck.

Eyal Avni: To take the cage from Bat Hefer.

Yochai Maital (narration): The custom-made iron cage, which yet another friend of Eyal’s had welded together on his moshav, was meant to help the body sink. But, as per Shlomo’s explicit instructions, there were large gaps between the bars, so that the fish could get in, and nibble away. Anyway, after picking up the cage in Bat Hefer, they made a pitstop at the morgue in Bnei Brak, picked up Shlomo, and hurried to the marina in Tel Aviv.

Eyal Avni: Everything synchronized amazingly. At 15:00, everyone met by the ship.

Yochai Maital (narration): Everyone met at the boat, and pitched in, loading a picnic cooler, or a tray of burekas or… a body, onto the deck, and they set sail.

Eyal Avni: All of us stood around the board. A glass of wine or a beer in our hand and we were telling jokes and telling stories about my dad and his special way of life. It wasn’t sad. It wasn’t sad at all. It was a lot of laughing sound, a lot of jokes it was so natural. Standing there celebrating, and his body’s lying in between us. It felt so right. At that moment, I knew that my father is very happy.

Yochai Maital (narration): At twenty-two nautical miles off of Israel’s coast, Shmulik, the skipper, silenced the engine. People stopped telling stories or joking around, and the sudden silence was quickly filled by sounds of waves crashing onto the hull. The family and friends onboard picked up the iron cage, tipped it over the railing, and then, gently, let Shlomo slide into the abyss. And as Shlomo’s body sunk to its final resting place, they each retreated to a corner of the yacht, and sailed back home in silence. Ever since, whenever I go to the beach, I think of Shlomo. I look to the horizon, and imagine the Mediterranean tunas and groupers staring – bewildered – at a sinking iron cage containing an old man, with a mischievous smile on his lips.

Act II: The Solitary One

This winter, Ruth Efroni, an Israeli TV producer and author, received a text message asking her to come to the funeral of a woman she didn’t know. She went. After it was done, she returned home, and wrote a Facebook post about it, which quickly went viral. In a gorgeous first-person narrative, we encounter the tragic solitude of lonely Holocaust survivors in Israel and see how, in their death, they occasionally find what they never had in life: a community.

Ruti Efroni (narration): Last week I went to the funeral of a woman I didn’t know. I got a text message that morning. It had words like “solitary,” and “childless,” and also “holocaust survivor,” and “3 o’clock.” So I said OK. I was gonna be in the neighborhood anyway, and was curious, and I guess I had nothing better to do.

As I walked into the Rehovot cemetery I wondered if anyone else would show up. But then I saw a large crowd near the monitor at the entrance, looking for her name among all the other people being buried there that day.

“Is this the solitary lady’s funeral?” someone asked. So I mouthed that word again – “solitary” – with what I thought was almost no voice at all. A religious woman holding a small book of Psalms put her hand on my shoulder. “It’s okay,” she whispered, ”none of us knew her either.”

While the rabbi was speaking, I counted us all – seventy-two people. Seventy-two strangers who came in the middle of the day, in the middle of shopping or working or picking up the kids or having coffee with an old friend. They were tan brown and pale pink, with yarmulkes or without, men and women, some very old, others teenagers with peach fuzz, who walked over from school after their teacher had read them that same text message.

And then the rabbi, beads of sweat glistening on his temples, asked if there was anyone who could say something about the deceased. Anyone? Anything?

No one budged.

I almost yelled out “me!” (you know, just to kill the quiet), but then I heard a murmur coming from the back of the group. One pint-sized woman – maybe 4’7’’ tops – cleared her throat and the crowd parted to let her pass through. She walked right up to the open grave, and stopped. “I’ll say something,” she mumbled. And in very broken and heavily accented Hebrew she said: “She had degrees. Much degrees. And she worked. Forty years she worked.”

A woman with pale yellow eyelids standing right next to me shook her head, and muttered under her breath, “a shiksa, that’s what she is.”

Then another woman spoke up, waving her closed umbrella against the blue sky: “The departed was from Odessa,” she began. “They didn’t have concentration camps in Odessa. They’d just kill you in street. But she managed to run away to Israel. And she’d write letters to those who stayed behind. She’d write ‘come to Israel.’”

“I’d like to add something too,” a man in shorts and sandals chimed in.

The yellow-eyelid lady said, “ah! finally!” as if she’d been waiting for this the whole time. So I asked her who the man was, and she replied, “what do you mean?! That’s Nachmani! That’s who!” I just nodded silently.

Nachmani knelt to the ground and took a lump of dirt from the grave in his fist. He said, softly, that this land was once his grandfather’s orange grove. “All of this was orange groves,” he declared, and then said that it was an honor for him that the deceased was now buried in this earth. “Amen,” he looked up with dry eyes, “may this land be good to us. May this soil be good to us.”

Just before people began to scatter, a tall fidgety woman, a municipal social worker, told the group that the departed refused to accept any help. “I’m good on my own,” she used to say. “Somebody to make you a cup of tea?,” the tall woman would ask, “to bring you a blanket? To help you get out of bed? No. She didn’t want any of that.”

It was the social worker who came up with the idea of sending out the text message. “This is an emergency,” she had pleaded with the folks at the Rehovot City hotline. “This woman has no one. No one but a bunch of strangers who may or may not get this text.” The thought of not having a minyan at the funeral shattered her. “And here you all are,” she said and her voice cracked just a bit, “I can’t believe you came.”

The yellow eyelids next to me were full of tears, and so were the tan brown ones and the pale pink ones. And those of the old and the young, the women and the men, the Jews and the shiksas.

So for one brief moment, in the middle of the mess that is our lives, we huddled together. And we were close. It is us, the living, more than the dead, who need this grace.

And I knew that we were all thinking the same thing: That it was too little and too late. That had we come sooner, one at a time, with a bowl of soup, or a smile, or just a kind word, then maybe she would have been less alone. And maybe we would have had something to say about her at her funeral.

So rest in peace Maya Chernichovsky, the daughter of Ben-Zion. For you had a lovely name, many academic degrees, and forty years of work. You wrote letters to your friends in Odessa and kindled your solitude like a caveman would kindle his fire. And you gave me a moment of tenderness, a moment of belonging. May your soul be bound in the bond of the odd life in this hard and beloved land.

Credits

All the music in this episode was composed specifically for the show by David Peretz of Be’er Sheva, and Collin Oldham of Portland, Oregon. You can find David’s Hebrew version of “Let the Mermaids Flirt with Me” here and Mississippi John Hurt’s original version here. The episode’s closing song is by the Israeli band Jane Bordeaux.

Wartime Diaries

Wartime Diaries